One of the things that used to intigue me when I was in medicine (in those occasional philosophical moments) was the fact that, though I spent my life combating disease, it was rather hard to pin down what health actually is. The 1946 WHO definition of health is very worthy, but totally impractical:

“A state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.”

Whilst I had a pretty holistic approach, I wasn’t going to sort out people’s social lives, and for some reason it was officially frowned upon to improve their mental well-being by sharing the gospel with them. But I knew reliably, if not infallibly, how to recognise “health”. In fact a couple of hundred thousand consultations gives one a Polanyi-type “personal knowledge” of what’s OK.

This reminds me of Arthur Jones (who has posted here), whose familiarity with cichlids, through his PhD work, enabled him to clock even one he’d never seen out of the corner of his eye in an aquarium. As a creationist, he sees that in terms of biblical kinds: my own preference is, as I’ve discussed before, the concept of there being an actual “form” or “essential nature” of species, which cannot simply be reduced to the happenstance of shared characteristics.

At the non-medical level this is borne out by cross-cultural studies of beauty. Though there are culturally-conditioned standards of perfection, there are also universals which suggest both an inbuilt concept of form, and an inbuilt teleology that recognises its ideal:

Symmetric faces are construed as more beautiful than asymmetric faces in all cultures (irrespective of the race of the person being evaluated and the race of the evaluator). You can visit Bedouins in the Middle East, the Yanomamo in the Amazon, and Inuits in the Canadian north, and they will all agree as to who is or is not beautiful (based on facial features). Clear skin is a universal preference. Certain morphological features that connote masculinity (square jaw) or femininity (high-cheek bones) are universally preferred. Rotund Rubanesque women, heavier women preferred in Central Africa, and catwalk thin models, while varying greatly in terms of their weight, all tend to have hourglass figures that correspond roughly to a waist-to-hip ratio of 0.70 (although cultural settings can slightly alter that preference). Babies who are insufficiently cognitively developed to be influenced by socialization gaze at symmetric faces for longer periods than they do at asymmetric ones.

In medicine there were of course, for certain laboratory parameters, “normal ranges”. But these have to be established locally (health and human form in Essex being subtly different, it seems, from health and human form in Sussex). In any case, one soon learned to ignore those outliers whose healthy sodium level was, ostensibly, in the pathological range. In my wife’s family there are at least three members whose ECGs strongly suggest they have acute anterior infarcts – they have to carry around their traces to stop zealous paramedics giving them streptokinase if they should faint. None has ever shown any evidence of heart disease.

One of course expects genetic variations. I have one myself: it’s a 2-4 gluconuryl transferase deficiency resulting in an unconjugated hyperbilirubinaemia, caused in all probability by a mutation to a recessive gene called UGT1A1*28. In English (or actually French) it’s called Gilbert’s syndrome. My enzyme operates at 30% of the usual, and so I sometimes acquire a lemon tint – as do 5% of the rest of the population with the same maladie. But here’s the thing – it causes absolutely no illness whatsoever. I once even wrote a joke article about starting a support group and making money for nothing. I am healthy, if different. But I’m not sure if my 5% are included in the normal liver function ranges: if so, we bias the mean bilirubin levels whilst still lying outside the reference ranges. If not, why are we considered pathological rather than just different? The fact is, there is a real norm, and we are outside it.

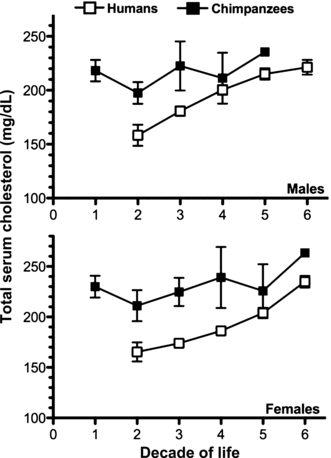

Another example: our allegedly closest relatives, chimps, get heart disease, but rarely infarction. Instead they die from interstitial myocardial fibrosis and cardiomyopathy, which is rare in humans. Yet they run cholesterol levels that would be considered treatable in us. But those humans whose serum cholestrols approach the simian range don’t have hearts more like healthy chimps: they just become sicker humans.

Another example: our allegedly closest relatives, chimps, get heart disease, but rarely infarction. Instead they die from interstitial myocardial fibrosis and cardiomyopathy, which is rare in humans. Yet they run cholesterol levels that would be considered treatable in us. But those humans whose serum cholestrols approach the simian range don’t have hearts more like healthy chimps: they just become sicker humans.

It’s as if the landscape of “form” is not an endless plain, but a series of craters which constrain normality. I’m in one shell-hole, and the chimps are in the next. It’s within those craters that variation is actually seen to occur.

These thoughts were prompted by a couple of articles on biological optimization. It’s an odd subject, because biologists tend to speak of evolution doing just enough to get by, and it’s people like physicists who tend to wax lyrical about how it achieves theoretical perfection. This video is a good taster – I particularly liked the stuff about the physical perfection of the compound eye. Whilst on eyesight, see this NYT article on the human photoreceptor’s astonishing ability to react to a single photon . My latest example is this piece from Phys Org about how the “back-to-front” construction of the retina, far from being an evolutionary botch as sometimes claimed, is a brilliant design feature enabling better vision through highly sophisticated principles.

These last cases are, of course, not incompatible with adaptationism. Perhaps natural selection sometimes jerry-builds, and sometimes perfects, though one cause with two different effects requires some explanation. But my medical background again shows me an odd anomaly, and that is that the eye appears to be a near-perfect design that’s seldom anywhere near perfectly instantiated. Briefly to explain, some stats on the commonest visual problems:

- Nearly three in 10 children (28.4%) between the ages of five and 17 have astigmatism. A recent study in Bangladesh found that nearly 1 in 3 (32.4%) of those over the age of 30 had it.

- The prevalence of myopia has been reported as high as 70–90% in some Asian countries, 30–40% in Europe and the United States, and 10–20% in Africa.

- Approximately one-quarter of the U.S. population is hyperopic, and incidence increases with age. Hyperopia is most common in the Hispanic population, next most common in Native Americans, African Americans, and Pacific Islanders, and least most common in Asians and Caucasians.

- Manifest strabismus affected 1 in 30 white and 1 in 47 African American preschool-aged children. The prevalence of amblyopia was 2% in both whites and African Americans.

- Red-green colour-blindness affects 1-10%, highly dependent on ethnic origin.

Astigmatism is another of my own familial traits, but until my myopia and presbyopia got worse it never disadvantaged me. The cross-cultural elements of these figures show firstly that possibly even a majority of people have significant visual impairment, and secondly that even in primitive tribal cultures it’s not bad enough to be selected out. In other words, evolution gets by very well by botching vision.

And yet the optimization stuff shows that the underlying design of the eye is close to theoretical limits: all of us have the fibre-optic enhancements, nearly all of us have the hypersensitivity to photons. And if we escape identifiable broken genes, a good proportion of us see pretty perfectly. It seems not to be a design issue, but a quality-control question. It’s mysterious to me how, given a constant background during evolution of poor image-forming, amblyopia, and colour defects, any optimization process should have got a look in at all. The design analogy would be a box-brownie with a plastic lens, equipped with imaging software from a state-of-the-art image-recognising robot.

The difference is that all the R&D of the latter has been done by manipulating images produced by the former. I don’t know how that could work. How can you optimize features of imaging without a reliably sharp image in the first place? You’d be just as likely to develop eyes in the dark, or an optical cortex without a retina. Even neutral drift has its creative limitations, despite the magical powers apparently attributed to it nowadays.

But one conceivable answer might be that the processes governing form are essentially separate from the processes governing reproduction, development and variation. Perhaps formal causation optimizes, and efficient causation “gets by.” That would account for both sets of findings – the existence of perfection and the evidence of improvisation; the reality of health, and the ubiquity of disease.

It’s a shame we’ll never find out, because nobody’s studying formal causation – although, returning to physicists, here’s what George Ellis of Capetown University was quoted as saying in Scientific American recently:

Einstein [in denying free will] is perpetuating the belief that all causation is bottom up. This simply is not the case, as I can demonstrate with many examples from sociology, neuroscience, physiology, epigenetics, engineering, and physics. Furthermore if Einstein did not have free will in some meaningful sense, then he could not have been responsible for the theory of relativity – it would have been a product of lower level processes but not of an intelligent mind choosing between possible options.

Physicists should pay attention to Aristotle’s four forms of causation – if they have the free will to decide what they are doing. If they don’t, then why waste time talking to them? They are then not responsible for what they say.

Maybe some biologists have free will too, and will take advice from another discipline.

Sociality could result in relaxed quality control…..