I’ve mentioned Rupert Sheldrake in a few posts, and his name has come up in comments, usually with the slant, “He’s probably nuts, but there are more things in heaven and earth…” In retrospect I have underestimated the extent to which we nowadays live in intellectually muddied waters (even here one has had to learn that “scientifically discredited” may mean no more than “Jerry Coyne’s trolls scoff at it”). There’s a long and interesting interview with Sheldrake on Best Schools, which shows that he’s read and studied a lot more than many of his detractors. That doesn’t make him right in his theorising, but it does make him more worth reading than many (as is, for example, Stephen Jay Gould, coming from a completely different position). His great strength is in investigating carefully what others dismiss out of hand.

My aim today, though, isn’t to evaluate Sheldrake, but to use some basic ideas in his approach to biology, which seem useful to me, to frame another discussion on divine action (using the conservation-concurrence-occasionalism framework we’ve discussed recently), and so maybe to open up our thinking to more possibilities. I hope that doesn’t prove too distracting a plan.

Let’s start with what got him started:

I knew from quite an early age that I wanted to do biology, and I specialized in science at school. Then I went to Cambridge where I studied biology and biochemistry. However, as I proceeded in my studies, a great gulf opened between my original inspiration—namely an interest in actual living organisms—and the kind of biology I was taught: orthodox, mechanistic biology which essentially denies the life of organisms, but instead treats them as machines.

There seemed to be very little connection between the direct experience of animals and plants and the way I was learning about them, manipulating them, dissecting them into smaller and smaller bits, getting down to the molecular level, and seeing them as evolving by blind chance and the blind forces of natural selection.

Well, a decade or so after Sheldrake I had the same experience with A-level zoology compared to Cambridge life sciences (we shared lectures with the biologists), but since I was doing medicine I just saw it as the way things were. In retrospect people disappeared from view in medical training just as organisms did in Sheldrake’s, and it took a long while before I fully recovered the realisation I was treating souls, not diseases.

Incidentally, Sheldrake’s spiritual experience casts light on another recent discussion here. Raised in a staunch Methodist household:

During the course of my scientific education at school, and then at Cambridge, I quickly realized that several of my science teachers were atheists, and that they regarded atheism as the normal position to have if you’re a scientist. It was just part of the standard scientific worldview; at least in Britain, science and atheism went together. I wanted to be a scientist, so it was part of a package deal, which I simply accepted.

I was the only boy in my school who refused to get confirmed at the age of 14…

So that’s one reason so many biologists are atheists. His journey through Eastern religion back to Christianity is described in the interview. It seems to me to underlie his science, though not to impinge on it any more than for most conventional biologists. In other words his theories are, in essence, naturalistic – it’s just that he has a broader take on naturalism than normal. I’ll return to that later.

I hadn’t realised before that the key to his thinking originated in the same kind of discussions we’ve had frequently on The Hump: the inadequacy of the efficient causation of physics, chemistry and received biology to account for form: in other words, the necessity for formal, and hence to some degree final, causation:

After Harvard, when I returned to Cambridge in 1964 and was doing research on plant development, I became convinced the molecular and reductionist approach would never enable us to understand the development of form.

Moving swiftly on, I want to consider the useful distinction he makes between his own approach and that of emergentists like Dennis Noble. Though both are approaches to “self-organisation”, “emergence theories” are seen to depend entirely on lower level molecular, atomic and ultimately quantum processes. They are “bottom up” in the same way as Neodarwinism, though postulating mysterious inherent propensities for complexity. Sheldrake, however, borrowing from the maths of “nonlinear dynamics” or “dynamical systems theory”, reverses the idea:

Dynamics is a branch of mathematical theory dealing with change, and a central concept in dynamics is that of the attractor. Instead of modelling what happens to a system by considering only the way it is pushed from behind, attractors in mathematical models provide an explanation in terms of a kind of pull from the future.

The principal metaphor is that of a basin of attraction, like a large basin into which small balls are thrown. It would be very complicated to work out the trajectory of each individual ball starting from its initial velocity and angle at which it hit the basin; but a simpler way of modelling the system is to treat the bottom of the basin as an attractor: balls thrown in from any angle and at any speed will end up at the bottom of the basin.

He refers to mathematical treatments of this by René Thom and Ralph H Abraham. In contrast,

Attempts to justify emergence, or the appearance of higher-level wholes from lower-level ones, based on physical or mathematical principles like phase transitions and symmetry-breaking seem to concede a reductionist approach from the outset: all appearance of higher-levels of organization ultimately needs to be explained in terms of fundamental physical particles.

I don’t agree with that. Physicists know very little about biology or psychology, and there’s no reason to assume that quantum principles that have a limited utility in explaining, say, the chemistry of simple molecules will explain the rest of nature.

Also, the usual use of the word “emergence” treats it as if more complex systems have emerged from simpler ones in a temporal sequence, so that larger wholes are always derived from smaller ones. But according to physics itself, this is not always the case. Modern big-bang cosmology starts from an initial cosmic singularity that contains all potentialities. As the universe grows, new forms and patterns emerge within it, including atoms, molecules, galaxies, and stars. But there is always a higher-level whole within which these lower-level wholes come into being, namely, the entire universe and the universal gravitational field.

I’ll leave the summary there, if I may. Ignoring the specifics of his own theory of morphogenetic fields (though he has a nice section pointing out that if these sound nebulous, electromagnetic and gravitational fields are equally vague, or representable only mathematically), the metaphysics he’s using is quite close to Aristotelian. Instead of the usual atomistic idea of chance and law gradually transforming particles into living things, somehow in nature the final forms are represented as principles that draw matter towards themselves. It is not so much that there is a target at which the biological archer aims, but a homing signal which accounts for the end point, however fluid the path travelled.

As I mentioned above, his programme is partly an attempt to demonstrate such an end-initiated process (hence the investigation of anomalies like action before knowledge in people and animals), and partly an initial attempt to account for it in a scientific way, albeit using an expanded science. In other words Sheldrake appears firmly committed to the reality of secondary causes. To couch that in terms of divine action (which, I guess, his avowed faith allows us to do), he is a conservationist, or else the kind of concurrentist envisaged by Eddie Robinson in his recent comment, that is one who sees God as seldom exercising any “rule bending” will in natural events.

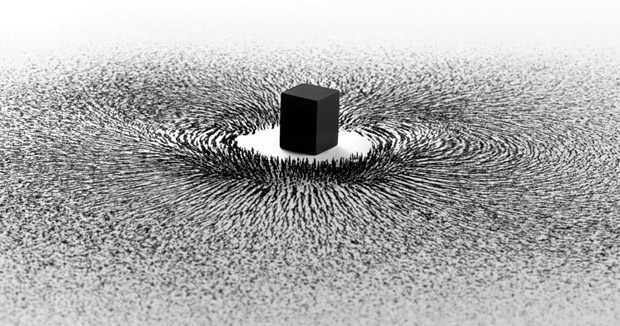

It may seem odd to consider Rupert Sheldrake, investigating things like precognition and teleology, as a “naturalist”, but I think that is his scientific intent. If we picture many modern theistic evolutionists seeing God somehow designing the conventional efficient causation found in physics and Neodarwinism to produce, on its own, just the world he wants from an initial explosion, we could similarly envisage Sheldrake’s God designing formal and final causation into the cosmos to the same effect: he chooses his ends, and they “suck”(as it were) the universe into existence from its singularity. If I were the Designer, I’d consider that a more reliable way of doing things – a magnet rather than a hand-grenade. Though even this may be misjudging Sheldrake’s position, I’ll go further and suggest that he might see even many miraculous events in the same “hands off” terms. And that’s where I want to start a new train of thought.

For supposing Sheldrake’s overall approach were accepted (and there’s really no reason why it should not be, at some stage, for comparable Aristotelian ideas of causation held the field for two millennia before Descartes & Co.) the back-to-front, form-first idea of causation would be just as capable of interpretation according to any of the three general theories of divine action – conservationism, concurrentism and occasionalism – as is efficient causation.

For supposing Sheldrake’s overall approach were accepted (and there’s really no reason why it should not be, at some stage, for comparable Aristotelian ideas of causation held the field for two millennia before Descartes & Co.) the back-to-front, form-first idea of causation would be just as capable of interpretation according to any of the three general theories of divine action – conservationism, concurrentism and occasionalism – as is efficient causation.

Consider an occasionalist Sheldrake, for example, who believed that God acts directly in nature, and that secondary causes are illusory. The interesting thing (to me) is that such a God would fit a literal interpretation of Scripture better than a God who intervenes in every efficient cause to push LUCA, say, along the path to the final animal forms. This God would, instead, set his goal, perhaps by saying “Let the earth bring forth living things according to their kinds”, and so draw the world towards the forms he had chosen. After all, that is how human intelligence works: we conceive of our goal, and then “pull it all together.” Just as I argued about “normal” occasionalism recently, one would be hard put to draw a sharp conceptual distinction between such an occasionalist view and a conservationist one: the maths of nonlinear dynamics would apply the same to direct divine action and Sheldrake’s morphogenetic fields seen as secondary causes.

We could also, quite comfortably, accommodate a concurrentist God to such a teleological science as to our current science of efficient causation. Whatever secondary causes might constitute the “attractors” that dictate biological forms, God’s sustaining hand could also block their effects in miracles, or modulate them in answer to prayer or in special providence. Contingency or human freedom would by no means be compromised – indeed, they might even be easier to acccount for than they are in the language of conventional science.

And this leads me to the last bit of this thought experiment, which is to try and bring about some linkage between the world of efficient causation and the formal/final causation I’ve been considering here. The big problem in thinking about divine action in the world of everyday providence is understanding how it can operate in a lawlike way accessible to science, and yet still be open to God’s guidance. Hence the recent discussion we’ve had about his “breaking” or “bending” the rules to answer prayer. But what if it were the case that there were some kind of separation between secondary, efficient, causes – sustained, indeed, by God but operating under law, or their own natures, whichever you prefer – and God’s “hands on” providence, deciding the goals or forms towards which they are directed?

In that case, it would appear there need be no conflict between the two kinds of causation, whilst both remained fully true. After all, if I’d decided to write this post on some completely different subject (which, perhaps, you might wish by now I had) then the operation of physical laws would have carried on regardless, but under the influence of a different “attractor”, the alternative column. Sheldrake actually appears to make a comparable case in distinguishing “form” from “information” as conceived in information theory:

I think that the phrase “its from bits” prioritizes a kind of atomistic view of information which is inappropriate for biological forms. I do, however, think that matter/energy consists of energy bound within fields which give form and pattern to the energy…

There have to be some resonances there with “The Son … sustaining all things by his powerful word.”

But before we can go there, someone needs to show that dogs do indeed know when their masters set out for home. Mine shows no such propensity.

I have little doubt that there are events that don’t fit the usual scientific account. There are too many stories of mothers suddenly awake and aware that something bad is happening to their kid. My own father, about as unprone to this kind of thinking/feeling as anyone could be, told me of having an uneasy feeling about a distant friend, calling and finding that the fellow was in a serious financial jam, which he was able to help with.

However, I feel pretty certain that the secondary cause vs. attractor thing are just different ways of talking about the same thing. I’m not up on the math of these dynamic simulations, but my impression is they are done with standard physics as the assumption. The “attractor” behavior arises from the dynamics working itself out. And I have little doubt that the form that emerges in embryonic development is a function of which cells stick to each other when and how tightly, programs of growth, cell polarity, movement up morphogen gradients, apoptosis of some cells triggered by feedback, and the like. My guess is “Morphogenetic fields” are just what it looks like when secondary causes are doing their thing.

I’ve seen some stuff from Sheldrake that was truly silly, like invoking some kind of developing field to explain why an experiment doesn’t work very well the first time you do it, because “the universe hasn’t gotten accustomed to it yet.” It always seemed to me that it had more to do with me designing and carrying the thing out better after some experience with it. You figure out what quantities are in the right range, how to space them out best, you improve at the mechanics of getting the stuff in the tubes in the correct volumes, and you realize the controls that you forgot the first time.

Agree with you about the silliness of Sheldrake.

Jon is wrong to think that science treats paranormal phenomena as “anomalies to be excluded from the intellectual universe” (from his comment below). Rather, ordinary experiences of the kind you describe are very hard to judge accurately. Your father may have had some reason (perhaps now forgotten) to worry about his friend, and his discovery that the friend was in financial problems is not particularly surprising–most people have financial problems sometimes.

I used to believe these sorts of things were real and indicated that there was more to reality than we thought. I hoped it would lead to new insights into physics. I spent my college years visiting paranormal researchers and doing experiments and reading theories (even back then, connecting this with QM was popular). But over time, after much study, I reluctantly came to the conclusion that there was nothing really there.

Once again WordPress has arranged so that I can’t comment on an earlier post (Dark Arts this time). So while I can comment on this one, I just want to say thanks to Eddie for his comment there, taking my comment seriously and understanding its relevance to that post (unlike all the other commenters on that thread).

The kind of event in my first paragraph, if anyone studied it, would have to go to the Journal of Irreproducible Results, and would be the first attempt at a serious paper they have ever received.

Hi Preston

Sheldrake’s observation is that virtually all of us have some stories such as yours, which actually cry out for a “natural” explanation, in the sense of not being due to special divine action, being sporadic and, in many cases, fairly trivial. The mother aware of her child’s need may be significant, but the dog aware of its master’s return, or anticipating who’s phoning you up, is not.

I applaud him for looking for a model in which they’re not mere anomalies to be excluded from the intellectual universe, but manifestations of a model of normal reality requiring explanation.

I can’t think of any way they would fit into standard cause and effect – though to be honest I’ve not investigated Sheldrake’s theories enough to know how they relate to his morphogenetic fields, as compared to more “conventional” effects of self-organisation like animal forms.

Nevertheless there seems to be some common ground, shrouded in fog, between his ideas, the weirder effects of quantum physics, Aristotelian causation and, when one thinks about it, the way God would direct his actions in the world if his thought were more analogous to ours than to a computer algorithm.

That’s all I’m trying to open up in this post.

As far as Sheldrake’s research goes, it would seem an uphill struggle to theorise on “mechanisms” when it’s so hard to gain acceptance even of the bare empirical reality of things such as those in your first paragraph. But his contention is not just that Lab A finds it easier to get a result after several goes, but that all Labs do. It would be interesting to read his data on that.

Maybe your dog does know when you set out, but just didn’t care right then. Diagnosis from a distance: Canine apathy. Check with your local veterinarian and ask what drugs might be available.

Yeah that’s possible. He doesn’t come when I call, let alone when I come home.