It doesn’t show much now, but when I was a kid I was quite a science fiction buff. I was eleven when Doctor Who first screened in 1963, and I remember sharing knowledgeably with my friends about what good sci-fi it was compared to most of what had been on TV.

That was certainly true: it took a stroke of genius to portray the TARDIS as having a broken camouflage circuit so it turned up incongrously as a London police telephone box amongst Daleks or Mongolian hordes. And likewise it was genius that it did not roar like a rocket, nor whirr like your average flying saucer or time machine, but instead groaned like a woman in labour as it strove to enter space-time, and sang like a whale when it had done so. The spacecraft was a living thing.

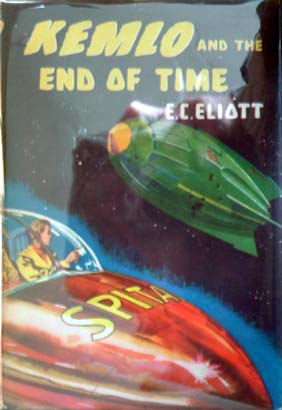

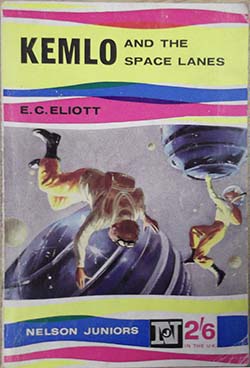

But my earlier acquaintance with the genre had begun with books like the Kemlo series by British author E C Eliott (a pseudonym for Reginald Alec Martin), whose characters were teenagers who, because born to crew of orbiting space-stations, were able to live in the vacuum of space – though space was not actually a vacuum but consisted of “plasmorgia”. Moreover, as the picture shows, they needed to wear breathing apparatus (with tanks of vacuum, I suppose) to visit earth.

But my earlier acquaintance with the genre had begun with books like the Kemlo series by British author E C Eliott (a pseudonym for Reginald Alec Martin), whose characters were teenagers who, because born to crew of orbiting space-stations, were able to live in the vacuum of space – though space was not actually a vacuum but consisted of “plasmorgia”. Moreover, as the picture shows, they needed to wear breathing apparatus (with tanks of vacuum, I suppose) to visit earth.

Some of the problems of nursing and educating these true children of space were mentioned, but the not inconsiderable problems of how Kemlo, his friend Kerowski, the younger Krillie etc (their names all began with the code-letter of their particular space station of origin) did metabolism without oxygen under weightless conditions – or even communicated with their parents and superiors, as they did, by voice-radio – were not. Nor was it really spelled out how being born in a space station entailed being adapted to vacuum: did parturition occur into a plastic bag? E C Eliott clearly didn’t come from a scientific background.

At the age of eight or nine, these problems didn’t worry me. Mainly this was because of the adventures themselves, which of course fitted the perennially attractive motif of “kids allowed to have adventures without the grownups”. But I do remember discussing it with my Dad, whose knowledge of science didn’t rise much above what he gleaned in RAF signals, but who read a better class of science-fiction than me. In fact, by the time Dr Who arrived on the scene I had graduated to purloining his Heinlein, Blish or Simak library books.

But though I don’t recall him as being cynically dismissive of my reading choice, he did suggest that the concept of vacuum-breathing space kids was more implausible than most. Of course, I didn’t know how much I didn’t know, and replied along the lines that one never knew what might be possible once man got into space, and that one should never exclude the unknown as impossible (or however a precocious nine-year old would put it). Of course, a bit of secondary school biology soon knocked some sense into me (except that I’d long forgotten Kemlo by then anyway), and my science fiction horizons were set on far more plausible scientific lines, such as the Dirac equations enabling hyperspace, merchants selling atomic hand-tools and the other accoutrements of classic sci-fi.

But though I don’t recall him as being cynically dismissive of my reading choice, he did suggest that the concept of vacuum-breathing space kids was more implausible than most. Of course, I didn’t know how much I didn’t know, and replied along the lines that one never knew what might be possible once man got into space, and that one should never exclude the unknown as impossible (or however a precocious nine-year old would put it). Of course, a bit of secondary school biology soon knocked some sense into me (except that I’d long forgotten Kemlo by then anyway), and my science fiction horizons were set on far more plausible scientific lines, such as the Dirac equations enabling hyperspace, merchants selling atomic hand-tools and the other accoutrements of classic sci-fi.

I was reminded of this by Sy Garte’s comment on the last post, in which as a novice in the Order of St Richard of Downe he found the evolution of tRNAs by the available mechanisms of variation and natural selection hard to swallow.

Now the point about Darwinian evolution (far more than its fashionable successor, neutral theory) is that to those who don’t know what they don’t know, it makes perfect intuitive sense. Living things vary don’t they? Only the fittest will survive, yes? Ergo natural selection is constantly watching over every detail of the living world, perfecting and refining all things (or however Darwin put in in the Origin). To the layman who once grasps it, it explains everything – and I mean everything – from cosmology to religion, as well as tRNA. It’s as flexible as the anthropic principle: if it hadn’t happened, we wouldn’t be here, and that’s sufficient explanation.

It’s rather like a certain kind of Creationist who thinks that scientists come to their conclusions in the same way they do: by snatching an idea out of thin air and then saying it’s so. Life is so simple when there are no details for devils to inhabit.

But then you come across some real difficulties during your education. For Sy it was tRNAs. Enzymes in general struck me as an impossibly put-up job at university. But there have been a number of other issues since – the evolution of DNA, the profound limitations of natural selection to operate on multiple traits, the discontinuity of the fossil record, the incompatibility of neutral theory and purifying selection with widespread optimization… things that, from my own experience, resemble very closely the discovery of the centrality of oxygen to human physiology and the subsequent reluctant conclusion that Dad was right, and Kemlo couldn’t happen. Crucially, those problems haven’t diminished the more I’ve read and studied. The proposed mechanisms all seem to exist – it’s the disconnect between them and the job that has been done that still troubles me.

The difference is that, unlike my skeptical father, ones seniors (like Sy’s professor) don’t see there’s a problem. “What biological evolution can do is truly remarkable.” Ones assumption would be that, come the Advanced Course or some background reading, the detail of just how evolution can evolve the tRNAs essential to evolution will be forthcoming. The detailed pathways to impossibly efficient enzymes will be revealed. A quantitative explanation of how a few thousand marvellous new traits were all selected for in the evolutionary blink of an eyelid to create a new species will be given – as will exactly how all that natural selection meshes with evolution by neutral drift that swamps natural selection. And so on.

But they never are, actually. Although the scornful “You clearly don’t understand evolution” put-down is as popular as ever, one can read all one likes and it still appears that the real subject matter of evolution, the origin of those endless forms most beautiful, is a matter of faith rather than science. The mantra of “testable hypotheses” is taken to include a host of hypotheses that have been a-testing for 150 years without actually being resolved. It’s science on extended credit. It’s apparently on the same level as the ability to spend billions on interplanetary exploration because we just know life is crawling about all over the place out there. But we have as much evidence for that, or any clue as to how it might arise, as for how Kemlo subsists on the aether in an unpressurised closet on the International Space Station.

And that is why, to me, Sy’s fielding of the idea of “providential evolution” (or however he finally labels it) is more than just a pious add-on to scientific evolution (which is what Evolutionary Creation tends to be – God is strictly unnecessary, but we like to make him feel wanted), but the only way to save it from the equivalent of throwing a seven with one dice. This feeling is not new, of course. It is what use to be called “theistic evolution” by those back at the dawn of the evolutionary age, like Asa Gray, Charles Kingsley and Benjamin Warfield.

In fact, to Alfred Russel Wallace, whose belief in cosmic spirits put the First Cause at a considerable distance, it wasn’t even “theistic evolution”, but simply the conclusion to which the evolutionary theory he had co-founded led him. He was probably wrong to call it a scientific conclusion (though he was adamant that it was), but surely not unscientific to refuse to put blind faith in the unlimited powers of an undirected process, which is not scientific either, but merely irrational.

When I was a child I thought as a child and the Kemlo scenario seemed an entirely reasonable likelihood. But when I became a man, I put away childish things… except when seized by fuzzy nostalgia. I wonder if any of the Kemlo books are online?