Joshua Swamidass has concentrated attention at BioLogos on the idea that the biblical Adam, as one common ancestor of the present human race, is scientifically viable, irrespective of genetics. That has focused my attention on the genealogies originating from Adam not only in Genesis, but in 1 Chronicles and in Luke’s gospel. The issue concerning me today is not directly how these support, or otherwise, the “Most Recent Common Ancestor” framework, but their purpose.

Both anciently and now, genealogies are not merely about descent, but about convergences and divergencies abstracted from what is actually a network of birth relationships – the fact on which Joshua’s MRCA hypothesis depends (though I was promoting it back in 2011, and others before that!).

A couple of generations ago British genealogy was all about trying to show royal, or aristocratic, lineage. I suppose that in a class-based society, although a grocer was never likely to inherit a title, still less the throne, nevertheless descent from the Duke of Norfolk on the distaff side gave one some sort of connection to Debrett’s Peerage, and a feeling that you were on the same playing field as ones social superiors. In the peasant’s revolt, John Ball quipped:

A couple of generations ago British genealogy was all about trying to show royal, or aristocratic, lineage. I suppose that in a class-based society, although a grocer was never likely to inherit a title, still less the throne, nevertheless descent from the Duke of Norfolk on the distaff side gave one some sort of connection to Debrett’s Peerage, and a feeling that you were on the same playing field as ones social superiors. In the peasant’s revolt, John Ball quipped:

When Adam delved, and Eve span,

Who was then the gentleman?

The answer wasn’t “Adam”!

Nowadays the aspirations might be different – a prosperous businessman might like to increase his street credentials by working class ancestry, or even descent from slaves. But no genealogist is interested in what everyone shares: heirs to a millionaire’s fortune might wish to prove how they are descended from him, but would not expend research effort on his great-grandfather.

Perhaps we can see this clearly from Matthew’s genealogy, which explicitly places Jesus’s ancestry in relation to his descent from Abraham, as recipient of the covenant of salvation, from David as recipient of the covenant of kingship, and from the exile as a reminder both of of Israel’s continued estrangement from God, and of the promise of restoration through Messiah. And for those purposes, Matthew has no reason to go back beyond Abraham.

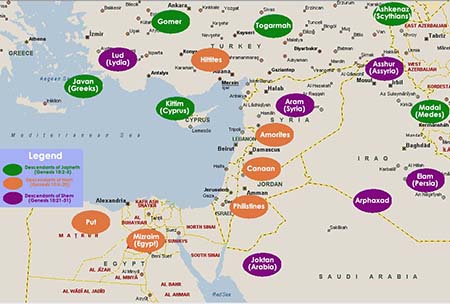

Now, if Adam in Genesis is assumed to have a universal significance as “first human being”, then his genealogy there may appear to be, in effect, a history of mankind’s spread. To assume this, though, one needs to see the Table of Nations of ch10 as implying a belief that it covers all nations, and that it supposes the Flood to have been worldwide: neither is necessarily the case.

Now, if Adam in Genesis is assumed to have a universal significance as “first human being”, then his genealogy there may appear to be, in effect, a history of mankind’s spread. To assume this, though, one needs to see the Table of Nations of ch10 as implying a belief that it covers all nations, and that it supposes the Flood to have been worldwide: neither is necessarily the case.

Rather, in the context of the Pentateuch the main purpose of the genealogy is to trace Seth’s line (“in [Adam’s] own image and likeness”, a phrase not used of Cain or Abel) – which clearly continues to revere Yahweh (eg 4.26; 5.23,29) down as far as Abraham, and thus eventually to Israel. The question to investigate is why this matters – it can scarcely be simply to prove that Israel belongs to the human race. Surely it has something to do with the story of Adam itself, whether Adam is seen as the progenitor of humanity, or primarily of Israel.

One link that has sometimes been drawn in the context of torah is the way that Israel is called by God, as Adam was, to live in a land “flowing with milk and honey” in the presence of God. Not only does this reflect the garden of Eden, but the triple promise to Abraham – people, land and blessing – reflects God’s original creation ordinance in Gen ch1 for man to multiply, fill and rule the earth and (by implication) do so on God’s behalf and therefore in relationship to him.

The Pentateuch records numerous rebellions of his “stiffnecked people”, and leaves the people on the brink of the promised land, with the question still open of whether they will inherit it, amid dark warnings that, like Adam and Eve, they might be exiled from it if they are unfaithful to the covenant. The torah ends by challenging Israel with a great hope based on obedience, and a warning based on Adam.

This makes good literary sense, but only really works if one sees Adam as, like Israel, called for a special purpose of service to God. In its direct application, at least, it does not take Adam as “all humanity” in his relationship to God and in his disobedience, for both Israel’s covenant and the penalties for breaking it are unique amongst men. If this line of interpretation is correct, the message of the genealogy is either “You are called to Adam’s role – don’t mess up as he did” or perhaps, more pessimistically, “Like father, like son.”

Something of this is possibly recalled in the Chronicles genealogy too, in that the book starts with “Adam, Seth, Enosh…” (the bane of generations of young Christians attempting to plough through their Bibles!), and ends with the reality of the Exile (expressed in Genesis-like terms as exact retribution for the non-observance of sabbath years, that is for rebellion from the government of God as in Genesis 2.2). And yet though we might spot such a connection, it is not actually stressed in the text: it is the genealogical descent from Adam that matters, and that in connection with the covenant. The table of nations is glossed over, as are the non-Israelite tribes descended from Abraham (though they are there). The greatest emphasis is on the line of David, and on the priestly descendants of Levi.

It is also significant that the royal line is continued after the exile, and the genealogies of some returning exiles are also given. The story of Israel and its kings is not yet over, then, and in some way it harks back to their descent from Adam. Surely it must be what is special about both Israel and Adam that explains the genealogy, and not that Israel are human like everybody else, even though other descendants of Adam are named in passing. It seems that just as not all descendants of Abraham are Davidic kings, so not all descendants of Adam are Israel, though both ancestries somehow validate their respective ministries.

If we turn to Luke’s genealogy of Jesus, unlike the others it goes in the ancestral direction to “Seth, the son of Adam, the son of God”. Now, the idea that Luke intends to prove Jesus’s divinity by tracing his ancestry to God really doesn’t work. In the first place, it would actually prove that every person descended from Adam is the Son of God, which is hardly an exclusive claim. Secondly, the genealogy starts with Jesus being son “as was thought”, of Joseph, suggesting that the genealogy is as much legal as biological. Thirdly, Luke has already said (1.35) that what establishes Jesus as Son of God is his Virgin Birth (we needn’t spend time here on exactly what Gabriel meant by that claim), so that the genealogy would be superfluous.

A second explanation is that, by this genealogy, Luke establishes Jesus’s solidarity with the human race, in its estrangement from God. This is possible, but it seems to me that a genealogy back to Adam is an unwieldy way of showing Jesus’s humanity, especially when (a) the genealogy begins with a “legal fiction” (3.23), and (b) when the genealogy goes back not to Adam himself, but to God. “Born of Mary” would prove the point equally well. Perhaps this explanation becomes a bit stronger if we note that Luke has already expressed some interest in the Gentiles, though most of his concern has been with Jesus as the king and saviour of Israel:

“For my eyes have seen your salvation,

which you have prepared in the sight of all the peoples,

a light for revelation to the Gentiles

and for glory to your people Israel” (2.30).

Even so, I return to that niggling detail that the genealogy goes from Jesus to Adam as “son of God”, not as “origin of sinful man”. Adam is nowhere else in Scripture referred to as God’s son – he was, after all, created from mere dirt, albeit enlivened by God’s breathing his Spirit into him. But I wonder if Luke, here, is extrapolating from an interpretive choice concerning that mysterious passage in Gen 6 in which the “sons of God” fall for the “daughters of men”, marry them and have children.

There appear to have been two common understanding of this passage in intertestamental times, as there are now. The first was that the “sons of God” were angelic beings who interbred with humans, their offspring being the demons that plagued mankind. The second was that the “sons of God” were Seth’s line, and the “daughters of men” people not descended from Adam (such as Cain’s wife!). In that case, it is the equivalent of Israelites marrying Moabites (Balaam’s temptation), with a strong suggestion of compromise in his holy calling.

If Luke believed something like the second of these, then Adam’s sonship would have been in relation to his appointment to a specific role, just as the kings of Israel like David were also known as “son of God”. Such a view would tie together the genealogies we have looked at not only in Luke, but in Genesis and 1 Chronicles. It would have to do with the purpose for which Adam was called, in which he failed, but whose future fulfilment was entrusted to his descendants in God’s wisdom. That would include the roles of Israel, her priesthood, and the Davidic kings, all of whose exile also demonstrated their failure to fulfil Adam’s intended function.

If Luke believed something like the second of these, then Adam’s sonship would have been in relation to his appointment to a specific role, just as the kings of Israel like David were also known as “son of God”. Such a view would tie together the genealogies we have looked at not only in Luke, but in Genesis and 1 Chronicles. It would have to do with the purpose for which Adam was called, in which he failed, but whose future fulfilment was entrusted to his descendants in God’s wisdom. That would include the roles of Israel, her priesthood, and the Davidic kings, all of whose exile also demonstrated their failure to fulfil Adam’s intended function.

But “a second Adam to the fight, and to the rescue came.” Jesus comes as the son of David, whose “kingdom will never end” (Lk 1.33). He comes to restore Israel, “to be merciful to Abraham and his descendants forever, even as he said to our fathers”(Lk 1.54-55). And he comes, as we have already seen, as “a light for revelation to the Gentiles”.

On thus understanding, then, genealogy from Adam primarily relates to the role God intended for Adam in history, a role transferred, and expanded with each human failure, in a convoluted genealogical succession right down to Jesus. It works whether Adam is seen as being given a role for a race that already existed, or a role as the founder of the human race. It works, too, for federal headship models.

What it won’t work for is if Adam is seen as:

- Fictional – in which case Scripture is just lying or misled. Whatever its conventions, genealogy is about real relationships – even in these Postmodern times, for a white person who identifies as a black to invent a family tree back to Africa would be considered illegitimate. And the Jews were very particular about genealogy: the latter part of the 1 Chronicles genealogy says that ancestry was recorded even at village level (9.22), a significant allocation of resources in a semi-literate society. And in Ezra we read that lack of solid genealogical evidence rendered returning priests ineligible for service.

- Typological – if Adam is simply a representation of “Everyman”, than any genealogy is as good as any other – and no genealogy at all more economical and less misleading.

- Biological – if one sees Adam as representing some first member of the species, back in the mists of prehistory, then the genealogies are absurd: to skip a few generations (as Matthew does, consciously) may be legitimate, but to represent 60,000 or more years by ten generations or so is just meaningless.

If, then, the principal purpose of the genealogies is to indicate the transmission of a hereditary role given by God, then literal descent is important for those to whom that role is transferred. But the necessity for universal descent from Adam becomes less pressing in these passages, although questions about how both the knowledge of God and the curse of sin spread to mankind leave that a good question in its own right, depending on the model being considered.

But this would be a separate question. In my first musings on this recently, a friend pointed out that “pedigree collapse” implies that not only Jesus, but the whole of Israel, would probably be descended from David a thousand years after his time, just as all Europeans are proverbially descended from the Emperor Charlemagne. Yet even so Jesus was, in his own time, acknowledged to claim descent from David is a special way, as indeed (one early writer records) were the grandchildren of Jesus’s brother Jude, simple farmers who were, for a while, viewed with suspicion as possible revolutionaries by the Emperor Domitian.

In other words, the descent of all mankind from Adam is a separate issue, to which MRCA studies certainly contribute insights. But the genealogies are, it seems to me, all about calling – a calling to royal rule and priesthood, leading to repeated failure until the one came to whom it rightly belonged:

The sceptre will not depart from Judah, nor the ruler’s staff from between his feet, until he to whom it belongs shall come; and the obedience of the nations shall be his. (Gen 49.10)

Bravo! Put this one on your “best of” list. Lots of good thoughts to ruminate on. I disagree on your bullet points, as you know, but I’ll let that slide while I chew on this cud awhile. Haha. I would like to see you integrate these thoughts with the ANE king lists, and the great ages of the patriarchs. How does that fit into this interpretation? Probably a subject for another Hump post, rather than a long reply.

Two thumbs up!

Thanks Jay

As you suggest, the details of the genealogy in Genesis is a different matter from its purpose (just as my being the rightful heir to the throne depends on Queen Elizabeth I and me, not whether the plumber in between was called Sid or Sam.

The king list is intriguing in the context of Eridu Genesis and its parallels to Genesis, but I’m not sure one can say much more: the Genesis list is not, especially, about kingship, and if anything is mentioned of significance, it’s in relation to God.

Similarly, the patriarchal ages are big, as are those of the kings, but actually of a different order of magnitude. I don’t for a moment believe they’re literal ages, but whether they represent a literary convention of inflating the ages of important people (but on principles now lost), or (as I’ve seen plausible arguments) the numbers arise from translating various types of base 10 and base 60 figures I don’t know.

I don’t think it sounds very plausible that they’re real ages somehow skipping generations, because nobody seems to be able to account for the ages at which people beget their kids, or “then he died”.

So I normally assume chronology on the basis of normal life-spans, with possible adjustments for omitted generations. That puts Adam somewhere in the mid to late 4th millennium.

Why 60, 000 generations? why is not the bible truthful?

The lists make the important point of Jesus origins and mankinds. i do think the great ages before the flood were right. Animals too. why they grew so big and numerous in timeline issues.

The lists not only make a great true biological heritage but establish the boundarys around humanity and earth in existence.

there never was a hugh timegap of humans doing nothing .

we are too smart to be wandering in the fields.

Well, recent research suggests that wandering in the fields is sometimes a lot smarter than what modern “civilized man” does.

For a Christian viewpoint on the same lines this is Dr Dennis Burkett (whose daughter married a college friend of mine). An interesting presentation on how we have lost wisdom in many ways, rather than gained it.

Excellent post Jon.

Can you comment a bit on adoption in biblical genealogies? Jesus was adopted by Joseph, and this seems to confer something important to him. Are there other examples? If this is a live option, how does it interact with doctrines of original sin?

Glad you found the post useful, Joshua.

Off the top of my head I can’t think of significant examples of adoption in the OT (does anyone here remember any?), especially in the genealogy of Christ, though of course there are several notable examples of irregularity and marrying out: eg in Matthew some of the sons of Israel had “foreign” mothers, maidservants who became surrogate mothers under the customs of the time; Tamar was Judah’s daughter-in-law; if Boaz’s forbear Rahab was the one in Joshua, she was a Canaanite; Ruth was a Moabitess; Bathsheba was at the time married to another.

Assuming both Matthew and Luke to be authentic genealogies, the variations teach us some knowledge of “pedigree collapse” – Jesus being descended from two different children of Solomon.

Adoption into Israel, at least, may be assumed in the OT even though individual examples are not stated, from the crowd that Israel took out of Egypt with them, and by the knowledge (both from text and archaeology) that the nation grew by cultural assimilation of remaining Canaanites more than by eviction or eradication. Much later, of course, there was a formal system for becoming a Jew.

But as to your main question, which is about what actual “inheritance” may exist between Jesus and Joseph I have no idea, other than the forensic one that an adopted son, presumably, could inherit from his father. But the question of original sin, if we’re considering some kind of “Augustinian” transmission, would of course exist through Mary anyway- which is why the Catholics have tried to cleanse Mary’s nature by the sinlessness of the Virgin and the Immaculate Conception, in order for Jesus to be sinless: there are better answers to that.

However, my thinking has developed (partly through doing this post) into seeing the genealogies in terms primarily in terms of priestly/kingly calling from Adam to Jesus.

Original sin, on the other hand, I’m seeing more and more in terms of enculturation. We exist as human beings only because of our social context, and if Adam introduced sin into that context, then with the exception of Jesus we are born and raised in sin as much as we are born and raised in families or as language-users. Sin may not be in our DNA, but it is in our mother’s milk.

Genealogy does, of course, bear on that, since the spread of culture is closely linked to the spread of genealogical links.

I wonder about the adoption at the heart of Jesus’ genealogy.

This, to me, is a clue that genealogies are not primarily about biology. We can ask what is common between natural and adopted children. One commonality is inheritance of possessions, debt, and titles. Another commonality participation in the same culture, covenants, and wars.

These seem like much richer ways of thinking of original sin than biology. They also deepen my insight into the Incarnation. This gives weight to entry of Jesus into our sinful world, and elucidates the revelation that “He was tempted in every way that we are, but he did not sin.”

Is there a way to recover traditional conceptions of sin in frame?

Joshua,

I think you’ve opened up a nice can of worms for some scholar to get a PhD with!

On the one hand the “bloodline” is important, but on the other there is a pervasive Scriptural strand of a concept that’s maybe even wider than adoption, and more like “identification”. Reading Matt. 23 this morning, Jesus condemns the scribes and Pharisees on the basis of their descent from forefathers who murdered the prophets (v29-32). Yet he immediately goes on to call them “Serpents! Seed of vipers” – alluding to Gen 3.15, the serpent’s offspring at enmity with that of the woman, depite their being genuine Israelites by their family trees.

Back in Genesis, a non-genetic fatherhood is accorded to Jabal, the father of all pastoral nomads; Jubal, the father of all musicians; and possibly Tubal-Cain as the father of smiths. In terms of literary form, that’s as much a genealogy as that of Seth in the next chapter.

The idea of adoption is very much clearer, as I suggested before, in the NT, with Paul in Romans 9 acknowledging the importance of biological descent, but implying that Abraham’s true descendants are those with his faith, not those with his flesh.

But how it all impacts on original sin I’m not sure – I was unclear as to what you mean in your last sentence… perhaps you could re-frame it!

At the same time, it’s important in the case of Jesus to be careful in the matter of “adoption”, lest on the one hand one lapse into Monophysitism, which says that the divine Logos merely adopted an ordinary human being, Jesus; and on the other one fall into Adoptionism, which says that because of his virtues the man Jesus was adopted as Son of God. Ontology matters here!

Agreed – but then (he suggested provocatively… 😉 ), isn’t it possible that there are richer ways of thinking about biology than biology (understood genetically)? A dolphin doing his own phylogeny might acknowledge some clumping artodactyl as ancestor genetically. But isn’t it conceivable he would see himself as genealogically closer to an ichthyosaur? Likewise, marsupial and placental moles might have more in common than they do with kangaroos or bats respectively.

Developing such an idea under Darwinism, the selective power of the ecological niche trumps the genes to produce convergence: but other laws of form, or even the concepts in the mind of the Creator, would be equally significant. Throw in things like horizontal gene transfer and we’d be pretty close to common adoption, as opposed to common descent. There’s another PhD for someone…