At the back of our house we have a one and a half acre meadow on a steep slope. I went out this week to rake out some mole hills before they harden – it makes the mowing easier in the spring. I was surprised to find that one of the pretty roe deer that frequently emerge from the woods to browse there had decided to die – and only a short time before, too, as it was still warm.

We feel privileged that the deer deign to treat our home as theirs, often with young in tow, and on one occasion last year featuring a rather spectacular rutting contest between two bucks whilst my wife was actually out there. She had to shoo them away from the electric fence in case they got tangled up. So it was a little sad to have a death, but I guess not really surprising in midwinter, relatively warm though it is.

We feel privileged that the deer deign to treat our home as theirs, often with young in tow, and on one occasion last year featuring a rather spectacular rutting contest between two bucks whilst my wife was actually out there. She had to shoo them away from the electric fence in case they got tangled up. So it was a little sad to have a death, but I guess not really surprising in midwinter, relatively warm though it is.

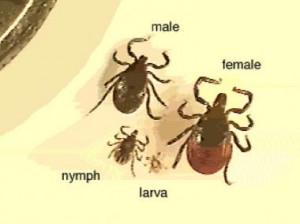

Not wishing to leave the carcase to decompose in our back-yard I dragged it off into the woods where, no doubt, it will provide welcome winter fare to foxes and the whole sylvian food-chain. That was the closest I’ve actually got to a wild deer, enabling me to conduct a brief external autopsy, of the kind I used to do on humans as a police surgeon at the scene of the crime. No signs of violence, which was a relief, as someone was firing a shotgun off all morning not far off. There was one well-fed tick on the back leg (there would have been many more in summer – I couldn’t help musing that the tick was condemned by the death of the deer). The doe (a deer, a female deer…) had quite a lot of mucoid secretions round her nose and mouth, and was not that well-nourished, making the likely C.o.D. respiratory infection or, possibly, starvation.

Returning from my disposal-operation, I surprised two young deer near the same spot, and supposed that they’d been orphaned – but they were around with their mother next day, so all seems well on that front.

As an aside, I wondered if my deer might have succumbed to Lyme disease (thus getting its revenge on the tick), but it appears from this interesting article that deer don’t actually carry the disease, which the ticks actually get when young from feeding on infected rodents. That seems to justify my catching a wood-mouse in our loft the same morning – a parallel death not as totally divorced from this tale as I had assumed!

As an aside, I wondered if my deer might have succumbed to Lyme disease (thus getting its revenge on the tick), but it appears from this interesting article that deer don’t actually carry the disease, which the ticks actually get when young from feeding on infected rodents. That seems to justify my catching a wood-mouse in our loft the same morning – a parallel death not as totally divorced from this tale as I had assumed!

According to one source, deer have a complex role in Lyme disease:

Comments Stella Huyshe-Shires, chair of Lyme Disease Action, “The role of deer is twofold: they spread the ticks, but they kill off the bacteria. Overall, we don’t know whether their net effect on Lyme disease is good or bad; nature has a habit of being complicated.”

Well, that’s true – nature is complicated. But is also has a reputation, amongst both Evolutionary Creationists and the Young Earth sort, for being cruel, which is one reason I wrote my e-book on the goodness of the natural creation, as a challenge to that view.

The YECs attribute all death, disease, predation and probably the very existence of ticks and Borrelia bacteria (unless they both once chewed green plants!) to the Fall of man. The common position I’ve critiqued amongst ECs, derived from the idea of nature’s “autonomy”, is that it was nature itself that fell from the start, developing like a Platonic Demiurge an evolutionary system based, it is claimed, on mutual destruction and self-promotion. This view has turned up regularly at BioLogos in the past (Darrel Falk, for example, denying any role for God in the intricacies of viral infection strategies, or the plague bacillus, or even the cat that plays with a live mouse).

The YECs attribute all death, disease, predation and probably the very existence of ticks and Borrelia bacteria (unless they both once chewed green plants!) to the Fall of man. The common position I’ve critiqued amongst ECs, derived from the idea of nature’s “autonomy”, is that it was nature itself that fell from the start, developing like a Platonic Demiurge an evolutionary system based, it is claimed, on mutual destruction and self-promotion. This view has turned up regularly at BioLogos in the past (Darrel Falk, for example, denying any role for God in the intricacies of viral infection strategies, or the plague bacillus, or even the cat that plays with a live mouse).

It leads quite frequently to a rewriting of the theology of sin in terms of the evolutionary struggle – George Murphy, for example, sees sin as “selfishness” more or less inevitably produced by our origin in the red-in-tooth-and-claw evolutionary struggle to survive. And so we have an example of doubtful science both feeding off and nourishing unorthodox theology (rather like the complicated deer tick life-cycle, I suppose), and misleading people about nature, God and – of most practical importance – the cause of the estrangement we have from both. The most thorough critique of that view of evolution and faith I know is Darwin’s Pious Idea by Conor Cunningham.

It leads quite frequently to a rewriting of the theology of sin in terms of the evolutionary struggle – George Murphy, for example, sees sin as “selfishness” more or less inevitably produced by our origin in the red-in-tooth-and-claw evolutionary struggle to survive. And so we have an example of doubtful science both feeding off and nourishing unorthodox theology (rather like the complicated deer tick life-cycle, I suppose), and misleading people about nature, God and – of most practical importance – the cause of the estrangement we have from both. The most thorough critique of that view of evolution and faith I know is Darwin’s Pious Idea by Conor Cunningham.

But I’m currently reading God Matters, by the late Herbert McCabe, who was one of those Catholic theologians dealing with the deep issues about God and, specifically, challenging many of the fashionable “improvements” in philosophical theology that, in fact, are superficial and incoherent in comparison with the wisdom of the faith over the centuries. I disagree with him on some things, but I like him a lot for the most part.

But I’m currently reading God Matters, by the late Herbert McCabe, who was one of those Catholic theologians dealing with the deep issues about God and, specifically, challenging many of the fashionable “improvements” in philosophical theology that, in fact, are superficial and incoherent in comparison with the wisdom of the faith over the centuries. I disagree with him on some things, but I like him a lot for the most part.

One thing McCabe points out is that the kind of things we see in the world – death, suffering, predation and so on – cannot be seen as an unfortunate by-product either of human sin or of nature-gone-bad. They are, instead, inevitable features of the kind of world God made – that is, a world of time, of change and of matter. The logic of such a world is that things can only change to perfect their natures at the expense of damage to other natures – that is the very essence of change.

Water can only bless us because hydrogen and oxygen ceased to be (and oxygen itself, in some distant star, was originally the product of the destruction of hydrogen and helium). A Stradivarius produces beautiful music only because of the destruction of spruce, maple and ebony as living trees. The fruit of “every tree in the garden” was food for Adam and Eve only at the expense of their basic role as seed-bearers for their kind. And the created nature of the lion, as so many of the early theologians recognised, is the glory of the predator, whose very “lion-ness” is achieved by the destruction of the natures of gazelles – yet whose “gazelle-ness”, in turn, involves not only their speed, agility and beauty, but their provision as food for the lion (Ps 104.21).

McCabe, in developing these thoughts, is consciously following a theological trail through Aquinas from Augustine, who wrote:

But it is ridiculous to condemn the faults of beasts and trees, and other such mortal and mutable things as are void of intelligence, sensation, or life, even though these faults should destroy their corruptible nature; for these creatures received, at their Creator’s will, an existence fitting them, by passing away and giving place to others, to secure that lowest form of beauty, the beauty of seasons, which in its own place is a requisite part of this world.

For things earthly were neither to be made equal to things heavenly, nor were they, though inferior, to be quite omitted from the universe. Since, then, in those situations where such things are appropriate, some perish to make way for others that are born in their room, and the less succumb to the greater, and the things that are overcome are transformed into the quality of those that have the mastery, this is the appointed order of things transitory. Of this order the beauty does not strike us, because by our mortal frailty we are so involved in a part of it, that we cannot perceive the whole, in which these fragments that offend us are harmonized with the most accurate fitness and beauty. And therefore, where we are not so well able to perceive the wisdom of the Creator, we are very properly enjoined to believe it, lest in the vanity of human rashness we presume to find any fault with the work of so great an Artificer… Therefore it is not with respect to our convenience or discomfort, but with respect to their own nature, that the creatures are glorifying to their Artificer. Thus even the nature of the eternal fire, penal though it be to the condemned sinners, is most assuredly worthy of praise.

And so my deer achieved the perfection of her nature (and what a perfection of grace and beauty, perpetuated in her fawns!) at the expense of the herbs of my paddock and the bark off some of my trees. She, in turn, sacrificed some of that perfection to the ticks, which in turn shared with the mice whatever cost they paid to the Borrelia bacteria.

And so my deer achieved the perfection of her nature (and what a perfection of grace and beauty, perpetuated in her fawns!) at the expense of the herbs of my paddock and the bark off some of my trees. She, in turn, sacrificed some of that perfection to the ticks, which in turn shared with the mice whatever cost they paid to the Borrelia bacteria.

The deer finally succumbed, I suppose, to another lowly type of bacteria or virus, but in death will now probably help perfect the natures of the mammalian and avian scavengers which also beautify our environment. At the same time she will also provide for the insects at the base of many food chains, and by her decay pay back the debt she owes to the soil from which her own sustenance came.

All this is to the glory of God – although we may not know why he made the world he did in the first place. And that glory is not lessened by the hope we have that nature, as well as we ourselves, will in the age to come be profoundly bettered, so that we are no longer “physically empowered”, but “spiritually empowered”. It doesn’t yet appear what alterations that will mean to the question of change, entropy and the interdependence of natures we see now. But I’m bound to remind myself to see wonder, rather than squalor, in what God has made for us in this age, including the stories playing out in my own local Eden.

And God saw all that he had made, and it was very good.

A few comments, if I may. First, this is a truly beautiful post, and although you have expressed these ideas many times before, somehow the truth of your vision really resonated with me in this piece. I love it because it is esthetically pleasing and at the same time entirely logical.

I also wanted to apologize for disappearing in the past month. One excuse was the busy holiday period, another was some medical anxiety, and a fairly unpleasant procedure that I underwent a few days ago. All is well, however, and I am now in the process of getting back to my delayed reading and so on. I did manage to post something on my own blog, which also has the theme of optimism during a time of great dread here in the colonies, (is it too late to petition the queen to be let us back in?).

Back to your own theme, I have long believed that actual evil is a human construct, and cannot apply to the “natural world” outside of humanity. Some have accused me of ignoring animal suffering, and I guess I need to plead guilty to that, at least theoretically. Your piece makes that point; I often think of watching a nature show about zebras, and then one about lions caring for their young cubs. The viewer tends to “root” for the prey in the first case, and for the predator in the second. This is because we are human, and as your quote from Augustine so brilliantly explains it: “because by our mortal frailty we are so involved in a part of it, that we cannot perceive the whole…” What I really love about this, is that while we often find it emotionally difficult to truly perceive the whole, that is one way to characterize the best kind of scientific investigation. So perhaps, Augustine is pointing to a great truth (one that I have long held) that the best science and the best theology both spring from the same mental and philosophical viewpoints.

And finally, Happy New Year to all.

Hi Sy – Happy New Year.

Sorry to hear my profession has made life unpleasant for you, but it’s worth it if all turns out well.

Also liked your piece on The Book of Works – I recommend your book Where We Stand to all our readers. I’ve noticed one or two pieces of good news evading the censors over the last few days – for example, in a piece on African state corruption they forgot to omit the massive economic improvement in the continent as a whole.

I guess we need to remember both the bestial and the angelic nature of man (as Blaise Pascal advised) lest we either become despondent or starry-eyed.

Anyway, glad you liked the pastoral piece. I’m convinced such a balance is vital for a right doctrine of creation, and that our doctrine of salvation rests firmly on such an apprehension of creation. We should be dubious of those voices that insist that Christianity is only about salvation, for the same reason that we should disagree with those who say people only need the New Testament.

As you say, science and fiath overlap here – if we weaken our doctrine of creation by positing evolution (etc) as an independent force, then it will pervert both our faith and our science – usually at the cost of divorcing the two, as you rightly conclude.

Sure thing – we need all the good people we can to help us manage Brexit and set Her Majesty up as Empress of the Universe. 😉

Jon,

Thought provoking post as usual. I’ve seen that “return to the Empire” option suggested on Facebook quite a few times in the last year, but I imagine you lose the right to move back in with your parents somewhere before you get to be 200 years old.

And now to the real issue. You mean I’ve been watching cop shows and murder mysteries for years, and all this time I knew a real police surgeon? When I think of all the irrelevant questions I could have been pestering you with…

You mean they won’t let me back into County Roscommon? ‘Tis a crying shame, so it is, begorrah.

I was never sure I was a real police surgeon when they called me out to take blood samples of drunken drivers at 3am. I finally decided I wasn’t and gave it up…

Jon,

Your remarks about Falk’s statements stirred up something with me related to a post on another blog I read recently. Philip Jenkins (Anxious Bench) was discussing the early gnostic view that the Divine Christ only descended on Jesus at His baptism and left at the crucifixion. On this early view, Epiphany (revealing) was not associated with the Magi, but the baptism. He gives a quote that he attributes to Irenaeus, but I think he really meant the gnostic Basilides:

“The father without birth and without name, … sent his own first-begotten Nous [Mind] (he it is who is called Christ) to bestow deliverance on them that believe in him, from the power of those who made the world. He appeared, then, on earth as a man, to the nations of these powers, and wrought miracles. ….

“Those, then, who know these things have been freed from the principalities who formed the world; so that it is not incumbent on us to confess him who was crucified, but him who came in the form of a man, and was thought to be crucified, and was called Jesus, and was sent by the father, that by this dispensation he might destroy the works of the makers of the world.”

What struck me in this gnostic quote is that the autonomous creation view of some ECs seems strangely similar to the gnostic view that the material creation is evil – it contains suffering and death and so the distinction of the principalities who created this world, one of whom may be the God of the O.T. (not entirely clear), from the true God, served the same function for some these gnostics as it does for some ECs, to distance God from the perceived imperfections of the world. And if the Nous (or Aeon) (God’s son) only descended on Jesus from baptism to crucifixion, it calls into question the real incarnation. Jesus during his ministry is only the form taken by God, not the union of God and man at conception and unto death. This form of Gnosticism seems to have lead to something like docetism. I feel like I’m not doing a great job of explaining this, so here’s the link to the post.

http://www.patheos.com/blogs/anxiousbench/2016/12/christmas-epiphany-birth-baptism/

Interesting Preston. I’m sure there aren’t many ECs who would want to be thought of as docetists – though there appear to be some pretty non-Chalcedonian ideas around in the “human fallibility of Christ” position that seems almost the opposite: Jesus is God before the Incarnation, but not in any real way in his life on earth.

But the distancing of God from creation seems a real enough phenomenon, with evolution clearly playing the part of a Demiurge which is even granted the personal attributes of autonomy/freedom.

But hey, I wrote a book about that, so I won’t labour it here!