Over at post 449 of 462 on the BioLogos debate between Dennis Venema (BioLogos staff member) and Richard Buggs (chief researcher in Plant Health at Kew Botanical Gardens) on population genetics predictions about early man, Richard replied to, I think, my only previous contribution on the thread. In that post I had ventured a concern I addressed in more detail in a post here:

To me the most significant thing about the debate (and something of an elephant in the room) is that all three serious participants (four, counting Gauger’s few brief posts) are engaged in answering this question: “Does the population genetics model support the possibility of a single couple, or not?” The answer appears to depend on what parameters are fed into the model, and similar technical issues. But that ignores entirely the question of whether the population genetics model is actually valid for such a situation and such timescales. And that rather depends on whether what it predicts (whichever way that turns out in the BioLogos discussion) can be validated by data, rather than solely by the output of the model itself.

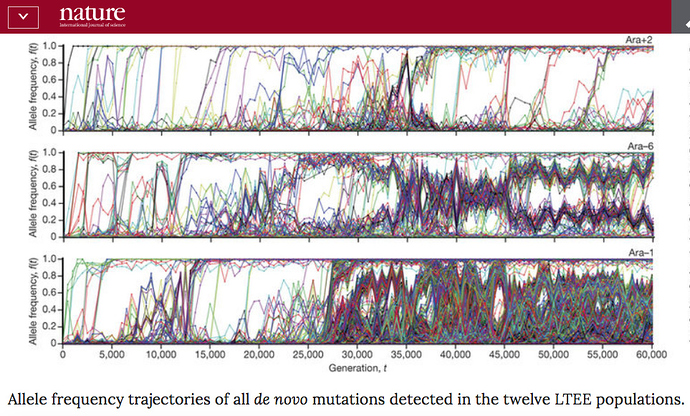

In his reply Richard essentially agreed with George (GJDS) and me that there is an issue about the extrapoltaion of population genetics modeling to the long time-scales of macro-evolution. But in support of this, he cited a new paper from the Lenski long-term E. coli evolution experiment, which compares the mutational history of all twelve lineages in the experiment down 60,000 generations. The results, summarised on a graphic, are astonishing:

Richard quotes Lenski’s comment in the paper:

Richard quotes Lenski’s comment in the paper:

Together, our results demonstrate that long-term adaptation to a fixed environment can be characterized by a rich and dynamic set of population genetic processes, in stark contrast to the evolutionary desert expected near a fitness optimum. Rather than relying only on standard models of neutral mutation accumulation and mutation–selection balance in well-adapted populations, these more complex dynamical processes should also be considered and included more broadly when interpreting natural genetic variation.

Richard himself concludes to George and myself:

I think this perhaps supports the point you were making. It is a very very different system to human populations, but in many ways it should be a simpler system, and therefore easier to model. It underlines the difficulty of going from models to real evolution.

If we were presented with the twelve different Lenski LTEE populations that exist today and asked to reconstruct their past, I very much doubt we would be able to detect the fact that they all went through the same bottleneck 60000 generations ago.

Now, without understanding the detail, the overall picture of actual occurrences over the course of the Lenski experiment appeared to me to resemble the kind of chaotic variation one would expect in, for example, the orbits of moonlets in Saturn’s rings or the development of weather systems. So I wrote:

…Lenski’s results are astonishing because they appear to show that the neglected factors “including: changes in mutation rates, periodic selection, and negative frequency dependent selection factors” seem (to me, at least) to result in a chaotic type of divergence over 60K generations.

Would that not suggest that such things cannot be factored in successfully, in order to correct the model over such timeframes, any more than additional factors would enable one to describe the weather a year ago from calculations based on the last three days weather?

I would add that this chaotic divergence is seen in Lenski’s model system, where the environment is entirely stable, reproduction asexual and the original population genetically uniform. To apply it to humans (or anything else) in the wild, one must also consider sexual (and non-random) reproduction, migration that’s far more uncertain after recent discoveries than this time last year (with the separation and rejoining of multiple breeding populations), known (and unknown) hybridization events, and an environment changing in entirely unknown ways.

My original point had been that models can diverge seriously from reality over time. This is because all models (such as population genetics) neglect elements of reality that are thought either to be minor and self-correcting (ie on average negligible), but which may not be in the long term (or which may be supplemented by entirely unknown, significant, factors). So for simple Newtonian two-body calculations of gravity, Jupiter and the Sun may be treated as point sources. This simplification breaks down in more complex circumstances, when Newton’s model cannot be used.

Alternatively the factors ignored by the model may be only slowly cumulative and therefore negligible in the short term, but more serious over longer time-scales. An example would be carbon-dating, which gives a reasonable ball-park estimate, though becoming increasingly inaccurate over time without external calibration.

But Lenski’s graphic suggests something I’d not anticipated: significant chaos within the whole system essentially invalidates any mathematical model over the long-term. If the same initial and subsequent conditions can produce such massively different outcomes, then back-tracking with a model from those outcomes will “predict” equally divergent histories and initial conditions. In other words, the model will be as useless for unravelling the distant past as meteorology is for describing the weather on a certain day 200 years ago.

My short post produced the anticipated riposte from another poster, “liked” by three other spectators:

To acknowledge some uncertainty in the estimate does not open the door to speculation from the peanut gallery that the numbers might be off by orders of magnitude.

At this point, consider for a moment whether the same slap-down would have occurred if I had not questioned the utility of a particularly entrenched scientific methodology, but some other source of knowledge. “The Bible does not spell this out…” – well, who could disagree? “There are insufficient historical sources…” – well, who could expect everything from the past to survive? “Philosophers may make false assumptions…” – well, obviously pure reason has limitations. But suggest a possible flaw in scientific assumptions, and the response is, “Touch not mine anointed!”. The experts, I was told, would already have pointed out any difference Lenski’s results made.

My comfort at the time was that one person had “liked” my comment – and that was Dr Richard Buggs. The reason is spelled out in a more recent post of his:

I think it would be fair to say that the ranges that Joshua @Swamidass is calculating from the TMR4A analysis do not include the uncertainty that would come from some of the more exotic effects that are evidenced in the Lenski experiment. It would be extremely difficult to do so. There is no way (that I am aware of) that we could trace the 12 Lenski populations back to one simultaneous bottleneck based only on their current diversity. This is especially true for the populations in which mutation rates have accelerated in the past, and then slowed down again. There are limits to what is knowable from present day genetic diversity, and there are some questions we will never be able to give a certain answer to.

One of the characteristics of Richard Buggs that has become clear in the whole course of the debate is his pernickity unwillingness to make, or allow, claims not borne out by strictly relevant calculations. It would, I’m sure, take an awful lot more work to see how the real-world (but highly controlled-world) data of Lenski’s latest reserach might affect the applications of population genetics, especially within the infinitely messier world of small populations of complex, sexually reproducing creatures that are involved in eukaryote evolution.

One might start by applying standard P-G models to each of the twelve current populations and seeing what they predict about their past history. But who’s going to make that effort when they just have to read Lenski’s reports?

But it seems to me that the question of a single-couple human bottleneck 600,000 years ago is a mere sideshow to matters of greater significance to science. How, I wonder, would such new findings affect the use of population genetics in the construction of the molecular phylogenies that now underpin our entire understanding of the tree of life? Maybe not at all. But maybe a lot. But is there anyone whose professional interest would tempt them to invest in that work?

Jon I believe you are misinterpreting that Lenski graphic and its relevance to the debate. Did you see my follow up question and Bugg’s response? The only effect Buggs thinks is relevant is mutation rate changes, and he also agrees that the variation is going to be much much higher in bacteria than in humans.

We should be careful about reading too much out of population genetics models, as you know I have been careful to note. However, there is also danger in reading to little out of them. We also have ways of measuring mutation rate differences in the past.

I do believe you are misinterpreting that exchange.

Joshua

No doubt you’re right – Your exchange with Richard hadn’t happened at the time I wrote this.

If only quick backtracks like that were common in the debate. Think how valuable that would be?

This gets to a stubborn paradox of practical importance.

On one hand, these questions are of too high importance to just “trust” experts to give us the conclusions. Not every expert put forward is being honest with the data or correctly representing it. There are agenda’s everywhere, and we are right to push for better explanations.

On the other hand, the data involved are complex and take training and aptitude to understand. So we do have to rely on experts to break things down, and be cautious about our naive instincts.

That paradox, I feel, is at play in this conversation. It is possible to explain the salient points of the data understandable ways. However, it is also easy to sow confusion and contempt of science too. Ultimately, I think we need both a Church that is willing to engage the data honestly, but also experts willing to explain the data honestly. Without ulterior agenda, to the extent that is possible. Sadly, that is just very uncommon.

Regarding Buggs, I’m very thankful for his contribution. I’m glad he has raised the questions he has. However, I am a bit puzzled what sometimes appears to be a reticence to state what the data appears to show: that a recent bottleneck (before 300 kya) is implausible. Maybe its just his style, and he is running through all his objections doing so. If that’s the case, there is no enduring problem here.

Of course, a better analysis might adjust that date, but this really seems to be an opportunity to make key feature of the world understandable to the Church. There is intrinsic value in honesty here, especially when so many people are confused about what the data does and does not show.

As we both agree Jon, for those that find a historical Adam important, and trust the Scriptural record, there is always the genealogical Adam too. So it’s not like this should be a scientific hill worth dying upon.

Also, I hope you post a clarifying post too. This is an issue of high importance, and our statements on this matter.

Joshua

We agree, it seems, on the paradox that our knowledge is always, necessarily, a mixture of trust and distrust, whether within or outside our own field of expertise.

That was, indeed, the point I was trying to make in the previous post, which I hesitated about posting lest it be thought simply to be knocking expertise. Instead, it’s about the habit of representing expertise as infallibility.

An example on the BBC yesterday, on a comedy (!) radio show, where the guest was a well-known scientist (as much as any are) making a very non-humorous bid to put the Large Hadron Collider in a museum as representing the triumph of objective rational knowledge over… all the things he didn’t like, including religion, of course. “If we ran the world like that…” – straight out of H. G. Wells’ “Things to Come”!

As for Buggs, my feeling is that he’s merely seeking to be as objective as he can. I’m not sure of his own position on origins, but there would be little to be gained by most varieties of Creationist in fighting for an Adam 300K years ago rather than 500K, or even more. Quite legitimately, he’s not bringing his convictions into the science. Though equally clearly, he wouldn’t be arguing if he didn’t agree with a a historical Adam or have great sympathy for those who do.

You might be right about Buggs. I hope so. Though some of comments seem to imply that TMR4A is a good argument against Venema, but cannot be trusted to rule out a single couple origin on a recent timescale. I understand why that is important to people, but then end we need to be honest about the data.

As for expertise, I do appreciate that you are not knocking all expertise. A challenge here is that most people cannot follow the technical details are are looking to us to sort them out. For that reason, publicly conceding points is important.

The detour into Lenski’s paper appears to be a total distraction if the only takeaway is that “bacteria can mutate much quicker than humans, so that effect has no bearing on these results.” In worst case, it is misleading. Likewise the concerns about recombination and the prior are demonstrably misplaced. I’m concerned that some people are just looking for a way to discount Venema, but still maintain we can’t trust these results enough to engage them as real (even if they will be refined).

In the end, I think we do have a compelling resolution in a genealogical Adam. So it seems the stakes should be lower for everyone.

Joshua

You’ll remember my medium term project is to try and show that the Bible writers were not unaware of people before and at the same time as Adam.

It seems to me a pyrrhic victory to be able to prove (or not exclude) a single couple somewhere around the dawn of Homo sapiens, when that makes virtually the whole of the rest of the Genesis story meaningless.

Let us imagine a purely hypothetical (!) situation in which 3 scientists, arguing well beyond public technical knowledge, for some reason can’t, or won’t agree on what the science shows. Unlikely, of course, but sometimes it happens 😉

The ironic thing is that people’s conclusions about the science will be driven by entirely non-scientific factors, such as which protagonist appears the most humble/evangelical/persistent or whatever.

You can see why there’s a recourse to “consensus” in controversial areas – but that too is a recourse not to science, but to democracy.

Tricky old business, truth! But it always was, and science doesn’t change that much.

Friend Jon Garvey,

Have you read the article on “Cheddar Man?” His corpse was found in Great Britain and was a pre-Celt. Why didn’t scientists call him Blue Cheese Man? HaHa

He’s actually a pre- pre-celt – various waves of immigration since the end of the Pleistocene, but Cheddar man seems amomng the first (and shares a lot of DNA with some of the current inhabitants of the village).

The next wave were the neolithic farmers from the middle east, then came the “beaker people” with broinze, and the (so-called) Celts from Iron Age Europe… before the Romans, the Anglo-Saxons, the Normans and my ancestors, from Ireland!

At easch stage, the founder effect probably ensured that more of the genes are still from the original settlers – though obviously dark skin largely disappeared, even though many Roman legionaries were African, until modern immigration.

Handsome chap, isn’t he?

When I first saw his picture, it scared me almost to death. I believe they could use him in a horror movie, or should we use him in a love movie.

Appearances may be deceptive – to me he most resembles a guy I used to know at university, a northerner with a rather dark complexion, who specialized in very emotional renditions of the folk ballad Matty Groves, sung to a small guitar.

Britain’s cheese expert and possible actor too. I see talent here.