There’s an interesting, and rather long, podcast here in which philosopher Lydia McGrew calls out New Testament scholars, as an entire guild, on what she perceives as systemic errors in their basic methodology, and particularly in the field of what is called “redaction criticism”. I have to say I agree with most of what she says, but there has also been a backlash from evangelical NT scholars contradicting her, partly on the basis of credentialism, ie that since she herself is not a trained New Testament scholar, she has no warrant to criticize those who are.

Now, the authority of professional, and particularly, academic groups is a fascinating question. In this particular case, McGrew speaks from her own professional expertise as an epistemologist – that is, she is trained in the business of how knowledge is acquired and evaluated, and finds a lack of such expertise in New Testament studies. So which is it? Does specialising in an academic discipline such as biblical studies give you the best possible grasp of it against all comers, or does it rather tie you in to restricted ways of viewing it that may receive a valuable reboot from external criticism? As has sometimes been proposed, is a PhD sometimes an entry ticket to a clique practising groupthink?

The sad, and very human, truth is that it can be either. In my own profession, two heroes of nineteenth century medicine are often cited as overturning institutional professional ignorance and stubbornness. Ignaz Semmelweiss, when an obstetric assistant only two years qualified, began to discover how puerperal fever could be almost eradicated by medical staff handwashing. And John Snow, a London physician, after epidemiological studies during a cholera epidemic, famously persuaded authorities to remove a pump handle from a contaminated well, stopping the outbreak (though he admitted it was already declining rapidly as people had fled the area).

In both cases they were opposed by the consensus medical opinion of their superiors that disease is caused by bad air (miasma theory) rather than by contact with contaminants, and the moral usually drawn is that scientific observation overcomes entrenched tradition and ignorance.

On the other hand, one can take the example of the ex-private Adolph Hitler, who achieved astonishing military successes before 1943 by scornfully bucking the advice of the “professional generals”, until his impulsiveness and lack of real skill eventually showed through. The “so-called experts” had actually been right all along. Hitler being a monster, and history having shown him to be an ultimate loser, it is easy to portray him as an ignoramus who should have listened to the trained soldiers. But consider Alexander the Great, who established not just an empire but an entire Hellenic civilization, and never lost a battle, basically by tearing up the military rule book that had served his father Philip so well, and getting it right. The maverick proved to be wiser than his teachers.

Returning to the medical examples, it was not in fact ignorance that led the bulk of the medical profession to adhere to the miasma theory, rather than the contagion theory, of disease. “Bad air” explanations actually fitted much of the data better, and moreoever there were serious fears that basing practice on the contagion theory would lead to neglect of precautions that might prevent epidemics. Furthermore, miasma theory had been a fruitful “research project” since the classical period, and the entire therapeutic and preventive arsenal available to medical science was built around it – and make no mistake, by this stage medicine prided itself on being a true biological science.

The last points, of course, were what led to culpable error: it was impossible for the guild, apart from the “young bloods”, to contemplate that, not only were they making an error, but that the entire foundation of an established, worldwide profession based on rational science could prove to be wrong. But it did so prove, for all that.

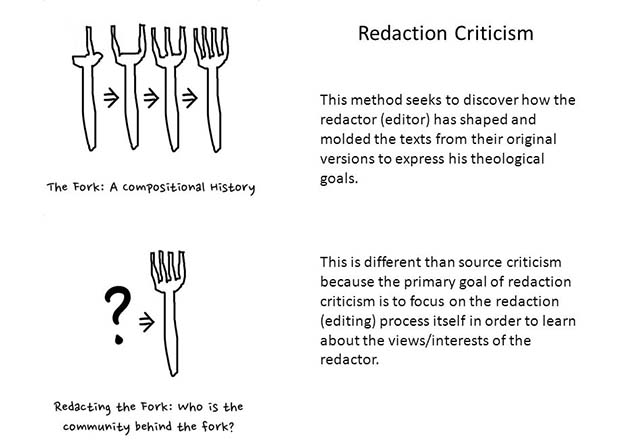

Now, there is a parallel with Lydia McGrew’s attack here. The methodology of redaction criticism arose from, and to an extent superceded, the older methodology of form criticism, which in turn depended on source criticism, which together form the backbone of all New Testament critical studies over the last 200 years. It is not surprising that a guild should be unwilling to accept that two centuries of basic methodology (and hence conclusions) could possibly have been built on sand.

Yet doubts have been voiced within the profession too. For example, the excellent Richard Bauckham wrote a wonderful satirical piece on this very subject here – and yet, McGrew was able to find examples in Bauckham’s own work of a complex and esoteric literary theory prevailing over a more simple explanation. (Bauckham argues that studies of the frequency of Jewish names shows that two Jewish first names rarely occur together, ergo “Matthew Levi” in the gospels must be two separate people, and Levi’s conversion must have been attributed to the apostle Matthew for some literary or theological reason. Yet in my college, at the very time Bauckham was doing his PhD in Cambridge, there was a guy called “James James” – rarities do happen, and statistics don’t disprove them.)

I know from my own medical experience that, however much one questions things from inside a profession, one still retains many of the limitations of the insider. In researching this piece, I read an article on the “pseudoscience” of phrenology, a theory that was only anything approaching mainstream for a few decades in the early nineteenth century before becoming a haunt for faddists. The writer, a historian of science, had the wisdom to note how, despite that, many of the science’s assumptions had survived in other fields, such as racial anthropology, and even how many of its predictions were proved right. Paul Broca, discoverer of the speech area of the brain, “Broca’s area”, was also “founder of French anthropology” and developed “anthropometry” to prove an evolutionary racial, and gender, hierarchy. You will find him arbitrarily designated as a great scientist in medical sources, because he got something right, rather than dismissed as a pseudoscientist, even though phrenology underpinned both his neurology and his anthropology.

I know from my own medical experience that, however much one questions things from inside a profession, one still retains many of the limitations of the insider. In researching this piece, I read an article on the “pseudoscience” of phrenology, a theory that was only anything approaching mainstream for a few decades in the early nineteenth century before becoming a haunt for faddists. The writer, a historian of science, had the wisdom to note how, despite that, many of the science’s assumptions had survived in other fields, such as racial anthropology, and even how many of its predictions were proved right. Paul Broca, discoverer of the speech area of the brain, “Broca’s area”, was also “founder of French anthropology” and developed “anthropometry” to prove an evolutionary racial, and gender, hierarchy. You will find him arbitrarily designated as a great scientist in medical sources, because he got something right, rather than dismissed as a pseudoscientist, even though phrenology underpinned both his neurology and his anthropology.

And yet the writer of the phrenology page I consulted failed to notice his own professional bias when he wrote: “And finally, today we know that what was traditionally called ‘the mind’ is indeed nothing more than functioning human brain.” “We” in this case presumably means all his materialist science historian chums, oblivious to the existence of serious philosophers, psychologists, neuro-physiologists and physicists who “know” no such thing about the mind. The bounds of reality truly are determined for you by which PhD you hold.

There is also an obvious parallel of the Biblical Studies case with fields to do with evolutionary biology. I’ve long been aware that biology is so broken up into self-contained specialities that not only do (say) population geneticists, often, have a completely different concept of evolution from (say) palaeontologists, but each appears unaware that their concept is not the sole one. Even within one field, adaptationists will insist that the consensus still holds that adaptive natural selection is the powerhouse of evolution, whereas neutral theorists will insist that everybody now knows better.

Sometimes it’s only the lay outsider who sees that untidiness, and only the one who doesn’t know his proper place who doesn’t simply defer to expert knowledge. To be sure, sometimes that “insight” is based on sheer ignorance: the lay outsider may simply understands so little of any of the fields he criticizes that he’s far more an Adolph Hitler than an Ignaz Semmelweiss.

But not always. As in Lydia McGrew’s case, it may be a situation of one field of expertise speaking truth to another – one ought to listen to the philosophers of science, or the nano-chemists, or the software engineers, or the mathematicians who question the assumptions of the Modern Evolutionary Synthesis, because not only might they have valuable relevant knowledge, but they will have a valuable outsider observation point.

I hope my main aim has come across in this piece – and that is to caution, maybe pessimistically, that one can place one’s security neither in the security of the professional consensus, nor in the wisdom of the iconoclast. One always has simply to do the best one can by maximising the knowledge – and wisdom – one has, using ones experience and reason, and recognising that one may end up being wrong. But one may also end up being right. Which is a bummer for anyone wanting certainty to lean on. But it’s a good habit to ask “What basic assumptions are held by my in-group simply because they may not be questioned?” That goes for religious affiliations too, of course.

To insist that science thrives on being wrong and correcting itself, and yet in the same breath to insist there is a curent professional consensus that warrants unquestioning acceptance from outsiders, is simply irrational, whether the science in question is biology, critical bible scholarship, or phrenology. The problem of uncertainty isn’t an academic problem – it’s intrinsic to being human.

My take home point, however, is that the solidarity of expertise is, in itself, no guarantee whatsoever that the experts are not fundamentally wrong. If somebody turns away criticism by suggesting the unthinkability that 150 years of biology, or 200 years of biblical scholarship, could get things completely wrong, then the rise of science itself proves that such revolutions are entirely possible.

As an instance, more fundamentally than the miasma theory of disease or redaction criticism, and even more fundamentally than geocentrism, there was a time when an Aristotelian approach to reality underpinned not only the whole of natural philosophy, but the entire intellectual life of the Western world. And it was swept away, not so much because science is intrinsically self-correcting, but because sometimes a new science – or more exactly a new philosophy – simply replaces the old en masse. It has happened, and will happen again, some day.

It’s not always as easy as it seems to know if the replacement is better, or simply more suited to the current zeitgeist. It’s certainly easier to go with the flow and look for a consensus to follow. Maybe, as the proverb says, “It is better to be average than right.”

“By any chance, does your claim appear in the scholarly literature?” – this is the trendy way that people who cannot address your arguments evade having to do so. It is really just the other side of the fallacy of “appeal to authority” formed as a question. Instead of using an appeal to authority to make a point, they use it to avoid having to consider one. They can insulate themselves from any claims that are outside their preferred academic circles. If you do happen to have some applicable scholarly literature they will invariably start looking for some reason why your chosen scholar doesn’t qualify to rate being considered. Indeed it is probable that no scholar whose research contradicted their previously held opinions would be “qualified”, because the primary motive for the charade is to insulate themselves from have to address the evidence for ideas which conflict with their own.

Mark

I suppose there’s in most fields a kind of “accepted range” of dissent that expands knowledge, and boundaries which one can’t cross, tending to squash knowledge.

It’s really the human condition, I suppose: presumably the iron worker or grocer (even the robber!) has ways of doing things that newcomers or outsiders can’t easily change. But with academia, especially nowadays with so much professional specialization, the presumption is that “the specialists” are “the subject”. And that can, potentially, hold up change for a century or more.