Part of my low output here recently (apart from a cold, driving my car into a ditch, and dealing with a broken washing machine) is down to transcribing the second volume of the proceedings book of my Baptist Church, 131 pages of hand-written entries from 1778-1904. It is generally in pretty legible copper-plate script compared to the mere 58 pages of Volume 1, from 1653, which are largely in the crabbed handwriting of that period and considerably more difficult for a modern transcriber.

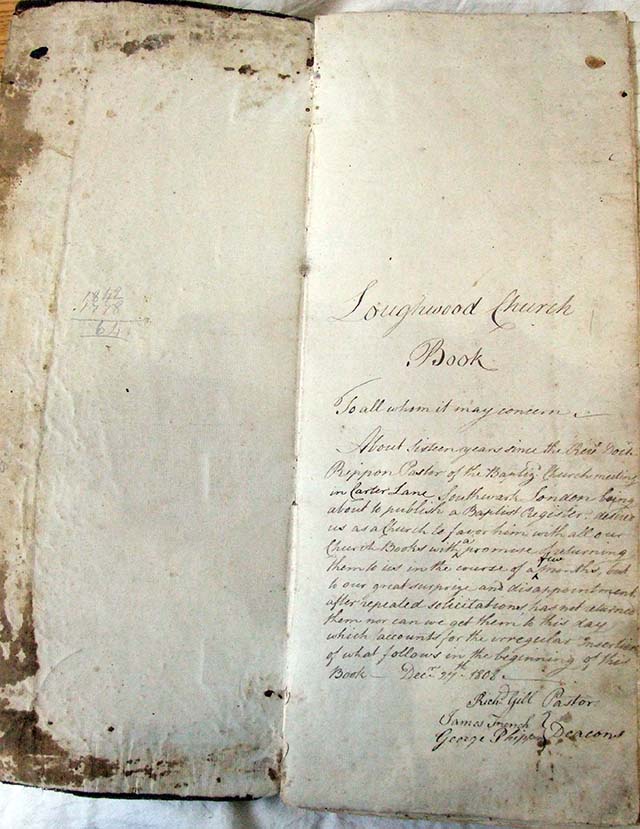

Both books are in the care of Devon Records Office, and therefore only really accessible to serious researchers. So my self-appointed task has been to photograph them there, and transcribe them so that our own church people, and anyone making enquiries of us, can have easier access. I covered the rather fascinating origins of the church here, but to read through 380 years of day-to-day chronicling of church meetings and other events gives a vivid picture of a small village church moving through the changing times, and yet staying faithful to its founding vision.

Like most historical material, much of the interesting stuff is picked up only by inference from patchy records. For example, the opening in 1833 of a second chapel under the same organisational umbrella as the original 1653 building is introduced in an entry making arrangements for the opening “next week.” Why it was thought necessary to go to the trouble and expense of a new buiding in the first place is not recorded. One wishes it were, for the two chapels were within walking distance (and subsequent annual events were spread over both), and a list of members at the time, just after the retirement of a longstanding minister, numbers only 14 people, though no doubt many more non-members attended.

That membership list coincides with a new church constitution, proposing excellent and very well-argued practices on baptism and membership, leadership, and church discipline tailored to this particular congregation, consciously differing from some common policies of the time. This exemplary 1833 work was signed, as I have said, by just 14 members, evenly split between men and women, and with a 4/7 literacy rate for both sexes (based on the signatures represented by a mark). The membership throughout the books, as one might expect in a Devon church, consists mainly of agricultural workers and more prosperous farmers and tradesmen, but not the higher echelons of society (despite our founding by Oliver Cromwell’s Adjutant General William Allen and Quartermaster General John Vernon).

Although numbers varied from lows like the 25 members, three in poverty, on the repeal of the Clarendon Code in 1668, to highs under some of the more dynamic pastors, it is not always clear what has caused the fluctuations. For example, in the middle of the pastorate of one of our most celebrated ministers, Isaac Hahn, a 1758 list numbers 28 women and just 4 men. Was this because Hann was becoming elderly and ineffective, or because (as one historian suggested) he lacked an evangelistic gifting? I have read a page or two of his sermons, and they are orthodox and biblical, at a time when many Baptist churches were lapsing either into Unitarianism or Hypercalvinism, so perhaps it was just that sound doctrine was as unfashionable as it has been in our own lifetime. Perhaps men in particular liked the trending ideas. But one alternative explanation is that between 1743 and 1776, John Wesley preached to big crowds in nearby Axminster four times, and his brother Charles once. Perhaps the attractions of the Arminian Methodists had for a time become the “latest big thing” to join?

It is nevertheless fascinating to see how this country church kept in touch with things, partly through the Baptist Associations that our own John Vernon had been so instrumental in founding even during the Civil War. A monthly Missionary Prayer Meeting is first recorded in 1828, and by 1879 annual Mission Services were held, with visiting speakers from the Bahamas, Jamaica, India, and China, and regular donations were made not only for Mission work but for famine and disaster relief. At least one member in the books, on her baptism, expressed a calling to mission work in China, and indeed she turns up in one of Hudson Taylor’s letters as doing excellent work in one of the China Inland Mission’s schools.

The church was quick to pick up on other Christian initiatives too. By 1860 they were celebrating anniversaries of their own Sunday School, which developed into a daily school. By 1891 there is also a Band of Hope, and in 1899 a Christian Endeavour group was started. They also joined the Temperance Movement bandwagon. They supported speakers from Dr Barnados and George Muller’s Orphanage, and brought in evangelists for special meetings (even US-style tent meetings) from Charles Spurgeon’s team and others.

Although the church, as a Particular Baptist chapel, had been slow to use music in church (1695 being the meeting that authorised it!), by the nineteenth century there are entries about providing or repairing harmoniums in both chapels, the Pastor’s wife is given a copy of Sankey’s Songs and Solos in 1884, the children present “services of song” on various themes, and the balcony at Loughwood Chapel even now bears a hole reputed to be for the stand of a bass viol – the best evidence we have that there was a “West Gallery” church band at some stage.

Politically too the church always sought to be involved. As early as 1659 they set aside a day of solemn thanksgiving for the Restoration of Parliamentary government on the abdication of Richard Cromwell. But they also had special thanksgiving when the West Indian slaves were emancipated and when the Boer War ended, and signed petitions against looser pub licensing laws.

When the Liberal Government passed a “Charter for the Villagers” in 1894, some of our members stood for election to the Parish Council and gained four out of seven seats – much to the chagrin of local Anglican farmers who boycotted the church’s tradesmen!

In 1902 members withdrew their children from the Parish School when they were told by the curate that they could not, as “heathen” say the Lord’s Prayer! It was, in fact, the refusal to pay the local “Priest rate” for a school they were not able to attend that led, in 1904, to nine members, including the dynamic pastor Richard Bastable, being repeatedly hauled before the magistrates and having their goods seized.

I should note in passing that an ecumenical spirit always flavoured the church’s dealings, despite the animosity of the local Anglicans. Anniversary speakers included Congregationalists, Bible Christians and even Wesleyans, and the church was even willing to baptize members of those churches with credo-baptist convictions.

But for all the changes, including some perhaps regrettable, such as the increased focus on the centrality of the Pastor, from what appears to have been a genuine every-member ministry in 1653, there is an astonishing continuity in these church books. And although a real sense of tradition was involved (we appear to have been celebrating the anniversary of our founding every year since the bicentenary in 1854, always in our original chapel), it is very clear that tradition plays second fiddle to the conviction that the Bible is our sole source of authority.

I have already noted how unusual it is to have maintained that founding principle, apparently uninterruptedly, over 380 years. The persecutions of the Restoration destroyed many Baptist churches. In the eighteenth century, as I mentioned above, Independent churches tended to go Socinian, General Baptists to become Unitarians, and Particular Baptists to become Hypercalvinists. In the nineteenth century Higher Criticism emasculated many churches. Yet the Church Books give the clear impression that Loughwood remained unfashionably, yet effectively, biblical throughout. And it is the fact that an Evangelical like me can identify spiritually with everybody contributing to these records since 1653 that provides the kind of small-c catholic continuity that the Church of England, for example, appears to have lost completely.

This is the kind of cultural continuity that so many long for in these chaotic times, not least in the current Christian revival that centres on historic, rather than progressive, faith. Today in the Daily Sceptic there’s a good piece by Dr Frank Palmer on this kind of continuity with respect to literature. But I think my final quote from that, citing T. S. Elliot, is also true for the Christian believer:

“No poet, no artist of any art, has his complete meaning alone. His significance, his appreciation, is the appreciation of of his relation to the dead poets and artists.” It is what Michael Oakeshott has called a “transaction between the generations”. It is the medium through which the dead can speak to the living and through which we enact our duty to the yet unborn.

This post brings back childhood memories. My parents were Strict and Particular Baptists and, throughout my early years, took me and my siblings to the (only) chapel that represented that denomination in Birmingham. For the uninitiated readers, ‘Strict’ refers to ‘restricted communion’ – only baptised members of that denomination could partake in the Lord’s Supper; in fact, you weren’t considered to be a ‘member’ until you were baptised; and you couldn’t be baptised until you had stood before the church and given your testimony; the members would then vote (after you had left the room) on whether to accept you or not. ‘Particular’ refers to ‘particular redemption’, the doctrine that Christ died to redeem the elect only, that the atonement was not universal.

Our chapel was opposed to the use of musical instruments; no harmonium; the singing of hymns was started by a chosen individual, Ronnie, who frequently got it wrong, usually pitching it too high; it was mandatory to finish the first verse, even if it involved screeching, and then Ronnie would re-start on a lower note. Membership was low – between 15 and 20, eight of whom were children.

We never had a pastor, so relied on itinerant preachers who, it was obvious even to a child, varied substantially in quality. If no-one was available to preach then a book of old sermons was employed, a deacon choosing which sermon to read; the favourites were by James Popham (1847-1937) and Joseph Philpot (1802-1869); both of these men were famous Baptists in their time. For a person of any age, but especially the young, Sunday chapel attendance was a dreary time.

I should say, however, that in due course I learned that my experience was not representative of the Baptist church in general. I had been the victim of a minority hyper-Calvinist Baptist sect, and much of what I had been taught was un-Biblical. In my late teens and as a university student I was exposed to a variety of more liberal religious environments and escaped the ‘shackles’ of the Strict and Particular Baptists; thus began a journey of discovery. Subsequent encounters with the Charismatic movement led to a complete transformation in my thinking; but it soon transpired that this was a mixed ‘blessing’! Indeed, on reflection it now seems like I transitioned from the frying pan into the fire. But that’s another story.

Interesting to compare, Peter.

The “particular” was, indeed, a theological distinctive (shared with other Reformed believers), but certainly in the 19th century we were not “strict,” there being a reference in the book to members of any true church being welcome to the Lord’s table.

I was also interested that the 1833 “covenant” I refer to in the OP specifically recognised the stress many people could feel from standing up to give their testimony, and substituted a private visit by pastor and or deacons for candidates, the notes of which would be read to the church, so that the candidate only had to say, “Yup, that’s my story OK.” I think public testimony remains optional in this way in the church, but I doubt it’s a conscious remembrance of 1833.

The voice-only music sounds like my last church years before i joined, when it was still a Brethren Assembly. I can only imagine that ours was acapella for a while after the singing started in 1695, given that Baptists had even warned of the dangers of having musical instruments at home: no doubt they’d have considered George Herbert’s lute a bad example. One of my friends attended a tin-tabernacle where guitars were banned, but the pastor’s wife played the hymns on syncopated piano!

I’m (as you know) interested in the attractions of the Charismatic movement to Evangelicals in the 60s and 70s, and not simply to those in the stricter sects. One reason I’m tossing around was inspired by Jonathan Edwards, whose work on Religious Affections makes the comparison between emotionalism (which he witnessed aplenty in the Awakening) and true religious feeling, as something like the difference between chicken nuggets and haut cuisine, or between comics and great novels. For the latter, you need some education of the soul, but also build up your soul, and I suspect that knowledge had dropped out of much popular Evangelicalism in the mid 20th century. So they wanted more (especially with the gurus and LSD-peddlars offering the transcendent round the corner).