In previous posts I’ve covered ground already trodden by many others in pointing out the dangers to individuals and churches of doctrines of Holy Spirit baptism and spiritual gifts that cannot be sustained from Scripture. I’ve also done a few posts (like this one) on how the theology of revival deeply associated with Pentecostalism, which has become the entire “evangelical” model, can actually pitch us against revival happening in other ways, through the Sovereign Lord’s wisdom and power. But today I want to make the claim that the Pentecostal/Charismatic “reclamation of the Holy Spirit” has paradoxically promoted a very low and limited understanding of the the third Person of the Trinity.

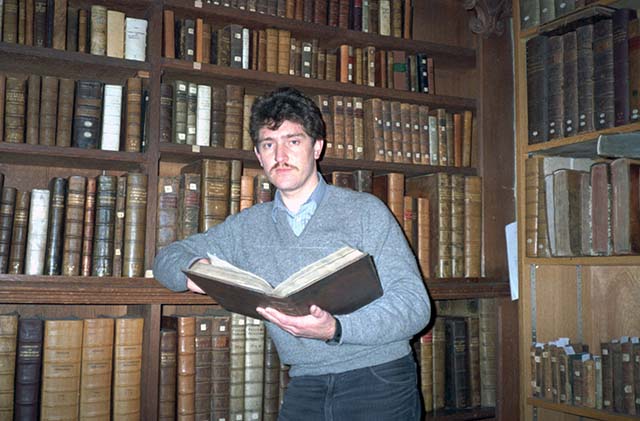

For such a big claim, I would like to recommend two big books. The first is John Owen’s 1674 A Discourse Concerning the Holy Spirit, weighing in at around 650 pages. It’s Volume 3 of his collected works, but I read it in an original edition in the Knightbridge Library in Chelmsford in the late 1980s, and it probably started my long journey away from Charismatic theology. What impressed me at the time, in this exhaustive study of the Scriptural teaching, was that it had virtually nothing to say on the “sign gifts” that so obsess us now, and of course nothing whatsoever about The Experience deemed now to be the mark of the “Spirit-filled Christian,” and the other experiences associated with it. Owen omitted them because that great theologian didn’t find them in Scripture.

However, recommending Owen to the average reader is a bit unfair, as not only is seventeenth century English tricky for us state-educated moderns to comprehend, but Owen has a particularly prolix and convoluted style. His substance, though, is second to none.

So my more direct recommendation is Michael Horton’s Rediscovering the Holy Spirit, coming in at a mere 334 pages, which covers much of the same ground (and cites Owen quite a lot), and has the additional advantage of addressing the modern “Charismatic controversy” directly.

Perhaps the most striking thing about Horton’s book is his central thesis that the Holy Spirit is involved in every work of God, because every work of God (whatsoever) is entirely Trinitarian. Therefore, to lay so much emphasis on the ministry of the Holy Spirit in the matters that interest Charismatics and Pentecostals is to neglect the importance of the Father and the Son in those same matters. And to neglect the role of the Spirit in all the other works of God is to limit him falsely, in effect, to the spectacular, the supernatural and the experiential.

These are among the least of the Spirit’s works in Scriptural teaching: in Matthew 16:4 the seeking after signs is condemned by the Lord because the greater work of salvation through his word was sidelined by a “wicked and perverse generation.” In some cases such claims about the Spirit are even contrary to the Spirit’s own teaching, as when “holy disorder” or “encounters greater than doctrine” are promoted as the work of the Spirit, when he is actually the God of order and peace (1 Corinthians 14:33). It is the Spirit who keeps our meetings orderly and peaceful – but less likely to be the Spirit that makes them cacophanous and weird. And it is the Spirit who both establishes pure doctrine (in the Bible), and bears its fruit in our lives. So it is the Spirit who brings biblical doctrine to life in us, but never the Spirit who teaches us that doctrine is secondary, or he would be denying himself.

Horton argues, pretty irrefutably, that everything God does is initiated by the Father as the Source of all things, given its shape by the Son, the Logos or Word of God, and brought to completion by the power of the Spirit, whose aim is always to bring glory to the Father and the Son.

The earliest example of this in Scripture is in the Genesis Creation narrative, in which the Father speaks creation into existence (through, we learn from John 1, his only begotten Son, the living Word), the executive agent of his power being the Spirit “hovering over the face of the waters.”

But even the world’s continued existence is the ongoing work of God – the Trinitarian God. Psalm 104 speaks of Yahweh’s ongoing renewal of Creation, whilst Hebrews 1:3 tells us that Christ upholds the Universe by the word of his power and Colossians 1:17 that in him all things hold together, because in him dwells all the fullness of God. Yet the effective agent of this sustaining is the Spirit, especially with respect to living things (Psalm 104:29-30), who was also involved when God the Father created Adam in the image of Christ and breathed his Spirit into him to make him a living being. This establishes that the Holy Spirit works as much through the natural order as beyond it, and can be expected to do so in our lives, too.

In the Incarnation the Most High Father sends the Son in human form through the Spirit (Matthew 1:18; Luke 1:35), and his commissioning is also a Trinitarian act as Jesus undergoes Baptism, the Spirit descends on him as a dove, and the Father’s voice affirms him from heaven.

Incidentally, Horton affirms that the works Jesus did as man were done through the Spirit (Acts 10:38-39), but this does not justify the error of kenoticists like Bill Johnson of Bethel and “progressive Evangelicals,” who misinterpret Philippians 2:6 to claim that Jesus left his divinity behind in heaven at the Incarnation. For from eternity, all the works the Son has done as God were also done through the Spirit. The giving of the Spirit “without measure” (John 3:34) is therefore a sign of Divinity, not merely of sanctified humanity.

The entire Trinity was also involved in Jesus’s atoning death and resurrection (see, eg, Acts 5:30; John 10:17-18; Hebrews 9:14; Romans 6:4). But just as in the historical redemption, our individual redemption in time occurs because the Father predestined us in Christ (Ephesians 1:3-6), and because his Spirit convicts us (John 16:8-10), incidentally through the Spirit-breathed gospel preached in the power of the Spirit (Romans 10:14-15).

The Spirit is also involved in the judgement of God, which is also described as the judgement of Christ, of which his conversion of sinners is actually as much an example as the death of Ananias and Sapphira, for conversion is actually the vindication of the elect in Christ, apart from his being the efficient agent of repentance, faith, and new birth.

I could go on for 334 or 650 pages, but I think I’ve made sufficient points for a blog post. But even in their preoccupation with spiritual gifts in 1 Corinthians 12-14, Charismatics seem to miss just what a Trinitarian passage it is. For a start, they fail to notice that πνευματικοι in 12:1 doesn’t translate as “gifts of the Holy Spirit” but “spiritual things,” an adjective pertaining to everything that comes from God, who is of course Spirit.

The indwelling Spirit is necessarily front-of-house in a passage on spiritual worship, but Paul is at pains to show the Spirit’s role as pointing to the Father and Son. In v3 he is the Spirit of God (usually, in Paul, shorthand for the Father), and is distinguished from demons by his promotion of Jesus as Lord (the translation of the divine name which Paul also customarily applies to the second Person).

Note also how, just as Paul wants to stress the unity of (Christ’s!) body, he merges the “manifestations” across the whole Trinity: in 12:4-6 “charismata” are from the one Spirit, “ministries” from the one Lord (ie Christ), and “operations” from the one God (ie the Father). Likewise the distribution to each member is governed by God in v7, and the Spirit in v11, the final beneficiary being the body of Christ. This is not because gifts, ministries or works are each attributable to different Persons of the Godhead, but because the Father is working all of them through the Son by the Spirit.

In fact, even the very indwelling of the Spirit is Trinitarian. Ephesians 3:16-19 shows how the indwelling Spirit somehow causes Christ to dwell in our hearts (by faith), and indeed for us to become vessels of the fullness of God. There is much holy mystery here, but Horton explores how there was an exchange of place when the incarnate Jesus returned bodily to heaven to intercede with the Father (so he is no longer on earth), and sent the Holy Spirit from heaven to his temple/body on earth, the Church, at Pentecost. This passage shows that the Spirit’s role is not autonomous, but intended, in an unfathomable way, to join us to the heavenly Christ, and through him to the Father. This, perhaps, is what Paul means by our being already seated in the heavenly realms (Ephesians 2:6). In this way it is also the Spirit who reaches up to heaven from our hearts so that baptism and the Lord’s Supper become true means of grace, and not mere memorials.

Given this far broader, and more Trinitarian, picture of the Spirit’s work than we usually see, it follows that we ought to perceive his work in more things than we do. It is not simply that with enough prayer and praise the Holy Spirit might come into our church. Rather, if those baptised into Christ (by the Spirit) in our church proclaim (in the Spirit) God’s word (written by the Spirit) and use the sacraments rightly, the Holy Spirit is already ministering there. We are filled with the Spirit already indwelling us, as we sing “psalms, hymns and spiritual songs” together – and they don’t need to be written or performed by uniquely anointed worship leaders.

As for πνευματικοι, it is the gifts of the Spirit (and the Son, and the Father) that constitute us as a church of Christ in the first place, rather than their being wonders to be longed for, always just over the horizon or disappointingly patchy.

If we are looking for a truly Christian experience of the Spirit, then I’m not sure why we should look beyond what he is said to do for us in the Bible, some of which I’ve outlined above. Though admittedly, the supernatural touch of Kenneth Copeland or Guru Mahara-Ji or a good dose of LSD, gets us high, if not holy, more quickly.