One of my current research aims is to demonstrate that the Bible itself has an awareness of other people existing in the world at the time of Adam, despite being overtly silent about them. I approached this from the point of view of the “compositional strategy” of the Torah and Tanach here, and from the point of view of hints about people other than Adam in the text here.

Today I want to take a look at a Sumerian text that might cast some oblique light on the solitude of Adam and Eve. That text is not the Atrahasis Epic, but I want to refer to that first since it is commonly compared and contrasted with Genesis, and with good reason because the two have many literary parallels.

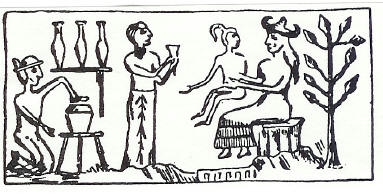

One key point taught in Atrahasis, and in a number of other Mesopotamian texts, is that mankind was created to ease the labour of the inferior gods. These deities had been assigned the work of irrigation (this was the Euphrates flood plain, remember), which was necessary for cultivation in order to produce both grain and pasture for livestock. The minor gods protesting (and in some accounts taking strike action!), mankind is created from clay and slain god’s blood, specifically for this role of agriculture and pastoral activity, in order to feed the gods, which is done via the whole cultic apparatus. This functional reason for man is central, because it is the gods’ hunger that later on ends the flood and has them all clustering around Atrahasis’s sacrifice “like flies.”

The parallel with Genesis is that both in Genesis 1 and Genesis 2, adam and Adam (respectively) are also created for cultivating work. The hugely important theological difference is that in both passages in Genesis there is a strong sense of mankind’s being created not as slaves to save God work, but as co-regents to admininster his world. But the point to remember for now is that, both in Genesis and Atrahasis, mankind is created for agriculture, appearing to suggest that before agriculture there was no mankind: in both traditions we were created de novo for a specific purpose.

Richard Middleton’s excellent 2005 book on imago dei, The Liberating Image, quotes another Sumerian text, Ewe and Wheat (formerly known as “Sheep and Grain”), whose text may be found here. Middleton’s purpose in citing it is to critique the Mesopotamian concept of man as slave to the gods (and its social consequences), but I want to pick up on something entirely different.

The story is basically a “disputation text” in which two gods, responsible for sheep and grain respectively, argue about their importance. But the story begins with a “cosmological introduction” in which the gods have trouble getting enough food and clothing, eventually resulting in the solution of forming deities responsible for inventing pastoral and agricultural activities.

If we were to seek to integrate this into the mythological structure of Atrahasis, we’d have to place it chronologically before the gods started doing those jobs, before they got fed up with it and therefore long before the creation of man.

But in fact, part of the Ewe and Wheat introduction says this:

The people of those days did not know about eating bread. They did not know about wearing clothes; they went about with naked limbs in the Land. Like sheep they ate grass with their mouths and drank water from the ditches.

Now whether these primitive people were simply invented to add relish to the story, or came from some residual folk-memory of life before agriculture (bearing in mind that, like Atrahasis, it comes from the very dawn of literature in the mid to late 3rd millennium), the fact is that it states clearly that people existed long before agriculture, whereas Atrahasis says people were created expressly for agriculture.

Now, I wouldn’t want to press the matter too far. We simply don’t know how far either Ewe and Lamb or Atrahasis were taken literally, or believed to be factual at all, in their original contexts. There may have been rival traditions on origins, or the culture may not have been that concerned with consistency between different stories – after all, even C S Lewis got continuity across stories wrong sometimes (for the curious, in the space trilogy, the significance of the hero Ransom’s name is given in the second book, having been revealed as a “pseudonym to protect the innocent” in the first).

But nevertheless both these stories come from the same culture, and were preserved by the same scribes for centuries, and they were able in some way to hold together the fact that Atrahasis, like Genesis 2, has man created for his role de novo; and that Ewe and Wheat presupposes people existing from time immemorial. These “former” people led an existence somehow removed from “people today”, whose customary labour of irrigation, farming and cultic duties is explained by the first account and not the second, whilst the “discovery” of that farming way of life appears in the second, but not the first.

Put more succinctly, absence of evidence of widespread humanity in an ANE creation text is demonstrably not evidence of absence, but only of literary purpose.

We can only conjecture how a Sumerian scribe confronted with this contradiction would reply, or whether his response would even make sense to our modern sense of logic. One obvious explanation, with possible relevance to Genesis, is that the scribe might say Atrahasis didn’t mention other people simply because it wasn’t about them, but real people like him. After all, when we say that everyone owns a mobile phone, we may tacitly accept that some cultural dinosaurs (like me!) do not, but it’s usually off our radar that there must be many remote tribal people-groups where nobody at all owns one.

It’s by no means impossible that, for a Sumerian priest-scribe with a highly functional view of things, bringing people together in cities so that the real gods were fed and worshipped correctly (thus holding creation together) was what constituted the creation of mankind in the first place, the divine blood and clay being figurative, and barbarians living long before or far away being simply irrelevant to his conception of “human” or “creation.”

Israel was not dependant on Mesopotamia for its beliefs, though it undoubtedly shared some of its thought-life. So if, as I have often contended, Genesis was written to the nation God called to transform the world, because Adam had failed to do so, then the history of Adam’s line is the story being told, and nobody else requires to be mentioned. But even so, people outside Adam’s line might be as implicitly present in the idea of the world that was to be transformed, as the non-Sumerians are when they peep out shyly from one small passage in Ewe and Wheat.

“One of my current research aims is to demonstrate that the Bible itself has an awareness of other people existing in the world at the time of Adam, despite being overtly silent about them.”

But is it overtly silent about them, or is the first creation account just saying a whole lot in very little space and the second zooming in on the line of Messiah? I think our English translations are silent about them but the text itself is not silent about them. Gen. 2:1 says that God finished the “heavens and the earth” AND “all THEIR vast array”. Look at that word translated “vast array”. Here is a link to an interlinear of the verse which shows you the Hebrew word which you can click on for a definition and to see how it is used throughout the text….

https://www.biblehub.com/interlinear/genesis/2-1.htm

The word is translated elsewhere “host” and always in respect to the earth means a large body of people capable of military action.

I don’t think we have to go outside the text of scripture itself to demonstrate the presence of those outside the garden.

Mark,

I think this online tool is easier to use for beginners:

https://www.blueletterbible.org/lang/lexicon/lexicon.cfm?Strongs=H6635&t=KJV

Of course, the King James uses “host” (aka “Army”) in place of Vast Array. Stars (as opposed to the “Wanderers”/”Planets”) moved in perfect lockstep around the Pole Star. And it was easy to conceive of such orderlineness as military in style.

But there are other clues in the O.T. regarding “the other people” that existed outside of Eden. Even the much maligned “fallen angels” end up producing their own alleged population of humanity.

That addresses the “host” of the heavens. But it doesn’t only say “heavens” does it? It also says “earth”. And I remind you they considered the stars to represent spiritual beings, sentient beings, so that even aside from the issue of the earth also being mentioned it does not solve the “problem” to say that they just meant the stars. When do the angels get created if not as a part of this verse (2:1) commenting on day four?

As for fallen angels producing humanity, that is not cannon. There is a much better explanation for Genesis 6:1-3 within the framework that J Swamidass and I share (and perhaps you do as well?) https://youtu.be/wc7BLlnSEbo

And that is just the most explicit mention of those outside the garden. Once Adam and Eve get tossed out of the garden the text sort of treats the existence of other people outside the garden as a given, without mentioning that they are there explicitly. Its just assumed. I may have posted this one here before, but its all right there in the text…..

https://youtu.be/GQ1rQ5RFUFg

Jon,

You mention that humans are made with a mix of clay and the blood of a slain God. What as the nature of the divine conflict with the slain blood? You will recall that the rivalry of Cain and Able was between the procurers of meat and the procurers of agriculture. And there is a “living” pool of slain blood. It would be awfully convenient if the Sumerian depiction of the slain god was somehow connected to lifestyle, wouldn’t it? (Naturally, I am skeptical that we will discover such convenience!).

The Persians have a myth of twin Gods where one god slays the other. Some have asked me if I thought this could have inspired the Cain/Abel rivalry.

I like the implied message you pack up in your column: could Eden have been intended as a divine plantation? And when “the help” get too uppity, they just “gotta go!”.

George

In Enuma elish it’s Kingu’s blood, he being the defeated consort of Tiamat who led the armies against Marduk. In the earlier tales they just seem to have chosen a couple of the minor gods from the workforce… which, matching the Sumerian society, tells you something about their valuing of thelives of inferiors. In all cases, Miuddleton points out that the emphasis seems to be on a despised source, rather than what you might assume – ie that humanity is elevated because partly divine.

That contrasts greatly with Genesis 2, in which God breathes life into man – there it does seem to indicate the spiritual.

The text says that Adam was put in the garden to till it and guard it, indeed. But though that has an agricultural, or at least horticultual, connotation, the words used are those used in the sacred service of the tabernacle or temple. So the best way to see the garden is as a sacred grove for worship, rather than a plantation for hungry divinity.

I didn’t intend to imply any kind of literary or theological interdependance between Genesis and the Mesopotamian texts, because that once fashionable idea is debunked. My comparison is entirely to do with literary convention – though Middleton sees the general Babylonian idea of man created as slaves of the elite being seriously subverted in Genesis – where all mankind, male and female at that, are created to rule under God. The view of mankind is entirely different.

Jon, your bifurcation of “barbarians” and “real people” reminded me of the discussion of Canaanites as “barbarians” within an ANE trope discussed in the Waltons’ (father and son) The Lost World of the Israelite Conquest. I don’t buy their application to the conquest (I.e., that the Canaanite were not being removed due to any divine moral evaluation, but simply b/c they weren’t in the Covenant), but the ANE background is interesting. I’d encourage you to check it out and see if it provides more fodder to your thesis.

Thanks KJ – another one to check out. I need all the fodder I can cultivate for the gods…

Another reasson one would not see them is because they were never there.

Why seek other humans? The bible expects its readers in the most simple and intellectual way to understand adam/Eve were not born and all humans who ever lived were born. At the flood all mankind died and this alone would make sumerian texts irrelevant.

At the fall our women were punished with childbirth pains. This never happens in female creatures and so would not happen in these “other” humans!

very strange to live with them but they don’t have that problem. Indeed the whole problem of death.!

From the bible its impossible to imagine the option of intelligent humanoid beings I think.