History has long been relegated to the humanities, on the basis that it is a narrative of fortuitous events rather than a natural process amenable to scientific laws. Granted, scientific tools like methodological naturalism have been applied, but inconsistently, to exclude divine miracles but not the equally unscientific attribution of human teleology to history. Similarly, teleology has sometimes been disguised as science, for example under the banner of “Social Darwinism” where human ambition was miscategorised as historical inevitability – its failure now being obvious to all. Only now has the unfolding of history been recognised as the obvious result of a simple and self-evidently real scientific process, which I summarise as “historical selection,” though it might be more accurately described as “survival of the serviceable.” At last history can stand on the same solid foundation as the natural and biological sciences.

Let me expand on this by way of explanation. History is, essentially, the study of the fate of nations and peoples. Two things may be observed from the start. Firstly, the survival of a nation depends on a struggle for the limited resources of the world against other nations, and there have clearly been many more nations that have succumbed than those which now exist. For example, what now remains of the Kingdom of Galicia-Volhynia, of Abyssinia or Nyasaland, but dusty remains in books or newer, more serviceable, states? Second, all nations exhibit a multitude of differences which enable them to acquire resources more or less effectively.

Taking these two undoubted facts, it is obvious that the nations with the more serviceable differences will be those which history (meaning all the pressures of the world environment) infallibly favours – a process I have dubbed “historical selection.” It therefore goes without saying that the nations we see today are those which have proved most serviceable to history, and that those which are no more have failed in the struggle – those in the distant past, of course, having needed quite different serviceable traits for what would have been a different world environment.

One might suggest that this view of history is both demeaning to the idea of human purpose and freedom, and somewhat tautological (though I consider it a much grander concept of reality than the alternative – the mere sum of trivial personal tinkerings). In fact, though, it has great explanatory power, especially in its more sophisticated mathematical expression in the recently published (2008) Hardleigh-Weindup Law that established the field of “population history”. This addresses the statistical behaviour of people, who are, after all, the basic unit of the nations that make history. The maths of the law is beyond the scope of this article, but in summary it proves that history will not happen if (a) there are no radical new ideas/inventions, (b) no existing ideas/inventions are better than any others, (c) there are no mass migration events (eg invasions, colonisations) and (d) the nation is of infinite size and all ideas/inventions equally likely to be passed on.

Since these criteria are seldom true, history is bound to occur and its course can be predicted simply by noting which of the four variables have changed under historical selection. In practice, simplifications must be made for such predictions, eg one must assume that historical selection occurs only on a single idea or characteristic at a time, which is admitted to be a gross oversimplification of reality. The law does, however, provide a basis for defining and examining history and makes certain predictions regarding the role of historical selection in changing population characteristics.

Hardleigh-Weindup calculations can only usefully be applied within the populations of nations, termed “micro-history”, but history itself is simply a scaled-up version acting on the same principles: it is studied by macro-historians rather than population micro-historians.

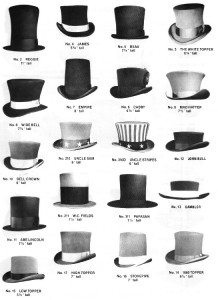

We can demonstrate its scientific insights, though, in the larger situation. For example, the top hat was first seen in Britain in 1793, and its use spread through the male population to become virtually universal in males throughout the following century, only declining in the first decades of the twentieth century.

This universality (termed “habituation” in population history terms) is an indicator that there was a historical pressure favouring the top hat, and that it therefore must have been a factor in the success of the nation as a whole. It comes as no surprise, then, to discover that the dominance of the top hat coincides closely with Britain’s greatest national and imperial power.

In contrast, look at these two contemporary examples of headgear that did not become habituated in the population and can therefore be assumed to have played no part in Britain’s historical success:

The first (unlike the top hat, not sex-linked) remains an extremely rare trait. The second appears to have disappeared altogether in the intervening century, probably by the process called “historical drift”.

By contrast, there are traits which are common, but clearly not subject to selection. This illustrates an example:

Here we can see long repetitive sequences of apparently purposeless elements (including clothing as well as apparent “headgear”). These again show no evidence of being selected, and so are considered to be end-products of parasitisation and only concerned with their own continuation. For this reason they are termed “PBI”, or “parasitic bearskin intrusions”. They are an object lesson in not attributing historical significance to what is merely common.

Consideration of the top hat example does not, in itself, explain why the turban, rather than the topper, became habituated in India (no doubt the climate and humity were factors), nor indeed why Britain gained ascendency over India. We may, however, conjecture quite probable reasons: for example, the top hat left more air space around the cranium than the turban, which might well have improved brain function. An recent alternative theory (Koolie, 2012) is that the time taken to wind a turban, compared to the shorter time needed to don a top hat, might well have tipped the selective balance in favour of the British.

Such examples demonstrate the complexity of the issues involved. Both nations, as they were then constituted, are now in the past, and likewise their environmental conditions cannot be completely reconstructed. Historical selection, then, can never be entirely a laboratory science, and some speculation is inevitable, but that does not detract from the evident truth of the theory. One cannot let lack of imagination – and particularly the “argument from doubt” to hinder progress.

After all, the only alternative is anti-scientific anarchy.

I enjoyed this history of headgear. I would like to see studies how the barbarian pants overcame the civilized toga and how the pants were destined to rule the world.

Cal, I’m surprised you can’t use the theory of historical selection to work it out for yourself scientifically. Clearly at some point prior to the invasion of the Goths in the sixth century, the selection pressure of the world environment changed, so that the Roman toga was no longer subject to selection, compared to the Gothic trousers. It may even have become deleterious to survival.

It would be nice to pin down what that change was, but strictly speaking the environment is outside the purview of history, which has to do only with nations. It might have been a colder climate, shortage of linen or other factors no longer accessible to science. So sufficient to know that, once selection pressure for trousers is recognised, one can construct a very plausible scenario of the gradual re-tailoring of togas into trousers – or perhaps they even coexisted for awhile until trousers were habituated in the population. Just so.