The word “bibliolatry” has cropped up in a comment on BioLogos again recently, interestingly without scare quotes, indicating that its validity as a word was being somewhat assumed. But buzzwords seldom foster truth. “Bibliolatry” used to be a word used by theological liberals against Evangelicals – it’s a sign of the times when Evangelicals use it against … well, that’s the question, isn’t it?

A comparable word, which was coined by Evangelicals, was mariolatry, directed against the Catholic cult of the Virgin Mary. Because of it Evangelicals have tended to throw the biblical Mary out with the superstitious bathwater, downplaying her role as both a role model and a prophetess, as well as shunning the very ancient term theotokos, “God-bearer.” It is forgotten that this term was originally intended to glorify Jesus, not Mary, at a time when, like today, his humanity was over-stressed by many. That Jesus was born fully God, as well as fully man, is the core message (the Greek Fathers weren’t in any sense kenoticists). For Mary in particular, and womankind in general, Christ’s refusal to “abhor the virgin’s womb” was pure grace.

And yet the term “mariolatry” has some justification. Nothing in Scripture (or the earliest theologians) leads one to suppose that Mary was sinless, or conceived immaculately; that she is Queen of Heaven or intercedes with Jesus when invoked by prayer, and still less that she answers prayer or grants visions of herself in her own right. Far from it: it is Mary’s humble estate that she emphasises in her Lukan song, the mark of God’s grace glorifying God alone. Like all its human role-models, the Bible points to some faults in her – Mary pushes Jesus to act “before his time” at the marriage in Cana, and Jesus even distances herself from her doubts by referring to his hearers as his “mother and brothers” when they ask after him. So it is possible to elevate Mary too high, even to the point of worship, and so make her an idol – even before you start carrying her statue round the town.

Can anything similar be said of “bibliolatry”? Nobody I’ve ever heard of worships the book as God, and few nowadays even reverence the Bible as an artiifact. There are some who, understandably, have scruples about abusing their Bibles – just as Americans do about abusing their flag. But even Fundamentalists are renowned for thumping, not worshipping, their Bibles. Like many Evangelicals I’ve been annotating the text of mine since I was a child – it has nearly as much pencil as print.

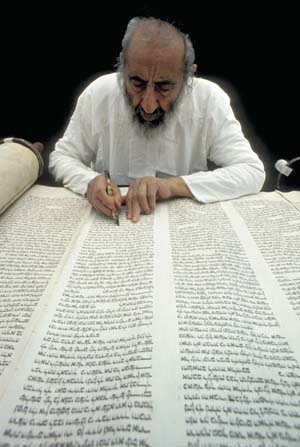

If the accusation of bibliolatry fits anyone, it fits the Massoretic scribes of the Talmudic period, to whom we owe the text of the OT we all use now, which is an oddly positive outcome from supposed idolatry: “Only skins of  clean animals must be used for parchment rolls and fastenings thereof. Each column must be of equal length, not more than sixty nor less than forty-eight lines. Each line must contain thirty letters, written with black ink of a prescribed make-up and in the square letters which were the ancestors of our present Hebrew text letters. The copyist must have before him an authentic copy of the text; and must not write from memory a single letter, not even a yod — every letter must be copied from the exemplar, letter for letter. The interval between consonants should be the breadth of a hair, between words, the breadth of narrow consonant; between sections, the breadth of nine consonants; between books, the breadth of three lines.” (Catholic Encyclopaedia)

clean animals must be used for parchment rolls and fastenings thereof. Each column must be of equal length, not more than sixty nor less than forty-eight lines. Each line must contain thirty letters, written with black ink of a prescribed make-up and in the square letters which were the ancestors of our present Hebrew text letters. The copyist must have before him an authentic copy of the text; and must not write from memory a single letter, not even a yod — every letter must be copied from the exemplar, letter for letter. The interval between consonants should be the breadth of a hair, between words, the breadth of narrow consonant; between sections, the breadth of nine consonants; between books, the breadth of three lines.” (Catholic Encyclopaedia)

So the term is far less strictly accurate than “mariolatry”, and actually just seems to mean taking the text of the Bible too seriously. And whether that is a just accusation depends entirely on what that text is considered to be. In human affairs, it is the writings of prominent people that best embody why they are prominent. Given the stark choice of possessing the works of Shakespeare, the Origin of Species or The Imitation of Christ, and having lunch with their authors, which would you prefer? In the case of most authors, we only know them through their words – Nobel Prizes are awarded because people write on weighty matters, not because they enthusiastically support football teams and take their kids bowling.

Now, clearly, knowing God is a different matter from knowing Tolstoy – like a love letter, the Bible is a way to find God himself, not (as Paul’s accusers said of Paul) weightier than the presence of the Person himself. But love letters are pored over and studied even after their author has died in battle or been lost at sea. They stand for the lover himself.

In Deuteronomy, Moses says that the manna was given to Israel so they might know that “Man does not live by bread alone, but by every word that proceeds from the mouth of the Lord.” In the wilderness context, “every word” meant nothing other than the torah given through Moses himself – those written words were more life-giving than food itself. Bibliolatry? If so, we’d maybe expect Jesus to correct it – but instead, he quotes it in resisting the temptations of Satan in the desert – indeed all three of his refutations of Satan are Scripture.

Now, the modern pejoration depends, perhaps, on the idea that the living Lord Jesus replaces the love letter by his presence in the world, understood either as his definitive work on the Cross, which makes any further words superfluous, or by his presence through the Holy Spirit teaching us so directly that we know better than Scripture – a distinctly Hyper-charismatic view, in point of fact. After all, the letter to the Hebrews begins:

In the past God spoke to our forefathers through the prophets at many times and in various ways, but in these last days he has spoken to us by his Son…

The Son, then, has come in the flesh and is superior in every way to what was before. But hold on there – note that the contrast begins by affirming that when Israel received prophecy, they were receiving not just the thoughts of men about God, but rather “God spoke”. That’s why, despite the “Christ event”, Paul still considers the Jews greatly advantaged because “they have been entrusted with the very words of God.” And to be frank, the “very words of God” shouldn’t become any less worth heeding because salvation history has come to fruition. Especially since, as Peter reminds us (1 Pet 1.11) it was the Spirit of Jesus himself who gave the prophets their words:

…for prophecy never had its origin in the will of man, but men spoke from God as they were carried along by the Holy Spirit. (2 Pet 1.21).

Against that, of course, is the testimony of moderns that these claims of Scripture, and of Jesus himself, are just untrue – the prophets did not speak God’s words – at least consistently enough to rely on. They are human writings, maybe with some core of divine influence. To put implicit trust in such words, they say, is to make an idol of human thought. But how to judge what that divine core is, which we may take as the basis of our faith? Well, for that we must apply our reason, and the reason of the modern (and therefore better reasoning) scholars, in a judgement based on our personal knowledge of Jesus. A cool thinker might conclude that we had just invented the heresy of ratiolatry, but there are already too many buzzwords flying about. Scripture just calls it “teaching as their doctrines the precepts of men”.

Incidentally, though, that chapter in Hebrews gives us a very clear idea of what the New Testament itself thinks of where the coming of Christ places the importance of Scripture. For a start, the writer is impelled by the Spirit to write the stuff down at all, so we may hear what God wants to tell us about Jesus. He doesn’t rely on the direct instruction of each believer by God. But in making his case, the Spirit also has him make the first chapter consist almost entirely of a series of seven quotations from Scripture, their truth assumed from their canonicity. Is that not as “bibliolatrous” as any modern preacher?

Finally, it’s interesting to ask if Scripture guards, in any way, against our being too reliant on it in the way that, as I showed, it warns us against being too reliant on the Virgin Mary. The answer is no – quite the reverse. Many passages extol the virues of the Law, the writings of the prophets and the value of the Scriptures to believers both in Old Testament and New Testament times. But never, even when Jesus strengthens its application or supercedes its provisions, does the Bible anywhere warn us that we should approach it only cautiously as a source of truth about God. That is significant. It shouldn’t need to be spelled out when the New Testament quotes or alludes to the OT canon many hundreds of times, and to virtually no other sources. But it is significant.

Given the constant warnings of the Bible against idolatry, the fact that it says nothing whatsoever about bibliolatry ought to make us pause before entertaining the concept as meaningful at all.