GD mentions in a recent comment how the Aristotelian concept of nature’s predictability is fundamentally different from that of modern science. To previous generations of natural philosophers, habitual actions were the result of the forms applied to matter by God. They were the intrinsic tendencies of substantial forms, and so part of their essential natures.

This could apply to very basic properties like what we call gravity: “Heavy things fall”, but also to the activities of higher forms such as living things: “Lions hunt.” “Bees make honey.” These are simplistic examples, but actually the most mathematical concepts of physics or “all there is to know about the life and habits of bank voles” are varieties of the same.

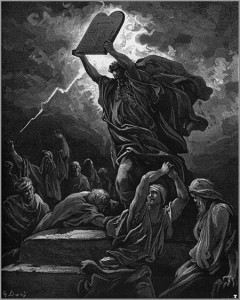

With the eclipse of Aristotle by the seventeenth century, the early-modern scientists chose to abandon the concept of essences, and substituted the idea of “natural laws”, a forensic idea taken directly from the Mosaic law. Just as God’s biblical law was something eternal and “out there”, which all men were commanded to obey, so everything in nature has to obey similar laws, decreed by God and written … well, here it gets nebulous.

They talked about how God’s laws were written, ie in the language of mathematics, but the whole idea only really makes sense if laws are somehow in the mind of God, because there is nowhere in the universe where a statute book of natural law is deposited, as the Decalogue was deposited in the ark of the covenant. So natural laws were seen as a parallel to God’s moral law – just as Moses was shown God’s character and, as it were, wrote it down as laws, so nature’s regularity reflects God’s character as Creator. Perhaps the natural philosopher can write it down for our instruction, but nature itself obeys God’s law instinctively: the stone has to fall in such a manner because the law of gravity “out there” says so.

This way of thinking, though now buried under centuries of metaphysically rather unreflective science, has far-reaching effects on how one thinks about nature – and about God’s role in it. But in fact, it is likely that it is based on somewhat of a misconception of the biblical idea of “law”. Remember that the biblical keyword translated “law” in Bibles since the KJV that underpinned early English science, at least, is torah, which means “instruction”, of which law codes are only a small part.

But the default concept of righteousness in Scripture is the natural internal inclination of the heart to good. In Eden, Adam and Eve were righteous because they were created that way, as in the Aristotelian conception, rather than because there was a law somewhere to which they complied. So what we might call “natural morality” (leaving aside the Fall) is not a universal forensic truth, but God’s specific creative intention for man, just as his creative intention for lions was to hunt. This nature is individual to man – which is why it’s so foolish to look on animal behaviour in moral terms, when one should be looking at God’s endowment of their diverse natures as right for them. Human nature is moral not because it is a universal cosmic truth – though it is universal amongst humans – but because, as rational creatures, we can choose to rebel.

Because we are in God’s image, there is indeed some analogy between our particular nature and God’s character, as distinct from lions or malarial parasites – but it is not an exact match of humans to “God’s law” as “God’s moral character”. God is righteous as God – we are to be righteous as humans.

For example, take the truth that “God is love.” I’ve been asked to preach soon on that passage in Colossians 3 in which wives are to submit to their husbands, who are to love them: children are to obey their parents, who are not to abuse them: slaves are to obey their masters, who are to provide justly for them. These assymetrical relations are chosen by Paul partly to show that the outworking of Christian love is role-dependent, not generic. The theological justification is the assymetry of the divine Father-Son relationship (Jesus always obeys God, though his ontological equal) and the assymetry of the Christ-human relationship (Jesus is always Lord, but he gave his life for us cf ch1.15-22) ). The Father’s love is never shown in subordination: our love for him is always thus.

Paul says in Galatians that “the law was added later because of transgressions”. “Later” in the text means “after Abraham”, whose righteousness came through a promise and was apprehended by faith. John Salehamer has an intriguing intrepretation of this is his tome on the Pentateuch. In brief, he suggests that Israel were intended, in their covenant on Sinai, to live in the same faith-rich, law-free manner as Abraham had. They were told to avoid the mountain for three days whilst they sanctified themselves, and then to come up and talk with God on the basis of the covenant he had already made (Ex 19.1-6). But the same lack of faith they had already shown on several occasions was repeated when they were too afraid, when the time came,to go up the mountain to meet God. They insisted Moses act as their mediator.

Salehamer says this altered the whole nature of their relationship – immediately thereafter the priesthood was added with its mediatorial regulations, and laws were given, in increasing numbers with each display of rebellion. What should have been an internal regulation (a return, in some measure, to the natural righteousness of Adam) became an external regulation of laws written down – good in themselves, and worthy of constant meditation as the psalmists and prophets say, but unable to bring about righteousness.

I’m about 75% convinced by Salehamer’s exegetical case so far. But even if he is wrong, and law was added because of some other trangression, it demonstrates the external and ineffectual nature of law as pointed out repeatedly in the New Testament. The aim of the gospel is for the law to be written on our hearts – that we should, through faith, take on the character of Christ, who is the perfect man, whose nature is always inclined towards God’s will and who is therefore in living relationship with him.

Does this theological discussion have any bearing on a Christian view of science? I suggest it does, because the modern scientific view of immutable external laws is very much more rigid and less dynamic than the biblical idea of natures (and nature) endowed by God with specific regularities, but also endowed with contingency making for variety, interaction with the Creator and, in mankind’s case, with rational choice. This is a picture that makes God’s relationship to his creation all of one piece – he deals with rocks analogously to the way he deals with people, through means appropriuate to their essential natures and his sovereign providence.

The forensic view also, it is true, has unity – God deals with nature by universal laws, and with humans by the same kind of regulation, given through Moses. What is problematic is the dichotomy pointed out by Edward Robinson in his reply to Darek Barefoot in the last thread. Why would law be fundamental in creation, but nature and grace the basis for God’s dealings with us? Why should mercy triumph over law, and immanence over transcendence in salvation, and a law less flexible even that that given to Moses (which is actually adapted to circumstances even between Exodus and Deuteronomy) be considered inviolable elsewhere?

Jon,

I would add the following. The notion of ‘laws of science’ is so ingrained within the scientific mentality that any debate would seem strange to a scientist. Yet philosophers do not seem to be particularly enthusiastic regarding this subject. Some comments found in an introduction to “Suarez on Metaphysical Inquiry, Efficient Causality, and Divine Action”:

“So even though what happens “always or for the most part,” to use Aristotle’s phrase, is sometimes epistemically crucial for discovering recondite causal connections in nature, the notion of a causal regularity is not metaphysically fundamental and hence will not figure as a primitive in an adequate account of the nature of causality or causal modality.”

“We all know that the regularity of nature so central to the more conventional picture is a pretence ….. Nature, as it usually occurs, is a changing mix of different causes, coming and going; a stable pattern of association can emerge only when the mix is pinned down over some period or in some place.”

“….. the fundamental explanatory principles of natural phenomena are ontologically grounded in natural substances themselves.”

I find the last quote especially interesting. Theologically however, I am inclined to think the central thesis is that of the intelligibility of the Universe. I think this can only be understood within the thesis that a human being is exceptional, and the intelligibility is theologically equated with what Paul clearly identifies as the spirit of man. Briefly, I think that enables us to ‘make sense of the creation (nature) to ourselves’; this capability is the result of purposeful and intentional human activity and the results (science and philosophy) reflect this sense of purpose and intent.

The following quote is relevant to your approach:

“‘empiricist’ accounts of causality did not originate with Hume or ….. (are) in fact following the lead of those medieval Islamic and Christian occasionalists who had perceived a ‘heathen’threat to God’s sovereignty over nature, as well as a spiritual danger for believers, in the Aristotelian attribution of causal powers and actions to natural material substances …..”

GD

Freddoso’s good, isn’t he? Intelligibility ceratinly seems the central issue that unites the disparate Aristotelian and modern approaches to nature’s regularity. As far as God’s “duty” to mankind goes, though, it’s really only important to know that things will always fall down (unless there’s strong wind or gunpowder around) – and it’s just as important to know that lions can be relied upon to eat you – usually.

In other words, we need enough regularity to make sense of everyday life, but have no reason to expect more. To hear some people speak, you’d think God is cheating us to make anything that’s beyond our understanding, eg quantum mechanics … and even more relevantly the daily interactions of forces both regular and contingent that make life only partly intelligible unless: as Freddoso says, “a stable pattern of association can emerge only when the mix is pinned down over some period or in some place.” Even then it doesn’t work when you start doing quantum experiments!

Freddoso is another of the many impressive scholars who brings us a wealth of insights, and perhaps more important, a way for us to exercise our God given intellect and reason.

I should have added, QM is done using the most sophisticated and accurate equipment known to us, and with criteria that is extraordinary in terms of experimental and theoretical rigor. It is odd to hear people discuss QM as something that is vague, probabilistic (whatever they mean by this), implying lack of exactitude. In fact it is the very opposite of vague etc., – but getting back to topic, it is human exactitude and intellect at work.