Our house, according to our neighbour (who was there) was built in 1969, but on a 2½ acre plot that was already surrounded on three sides by traditional “devon banks”, and on the fourth by a lane. So it’s a field with some kind of history, but mostly unknown to us as we’ve only been here eight years.

So I was pleased a week or so ago to find that a Tithe Map for the parish is now available online, dating from 1840. This was when the ancient system of paying the church tithes for the maintenance of the clergy and the poor was tidied up by Parliament, which ordered that maps and accompanying schedules of who owned what, and who paid rent to whom, should be drawn up.

I was able to see, then, that my property 177 years ago was divided into three lots (739-41 on the map), but under the ownership of one absentee landlord, who rented it to a dairyman (as I later found out) called Isaac Lane. The most fascinating thing was that, as the map shows, there was then actually a small cottage at the opposite end of the plot to the site of our house, in an area that is now an overgrown waste at the foot of a steep slope where we used to dump our stable manure.

I was able to see, then, that my property 177 years ago was divided into three lots (739-41 on the map), but under the ownership of one absentee landlord, who rented it to a dairyman (as I later found out) called Isaac Lane. The most fascinating thing was that, as the map shows, there was then actually a small cottage at the opposite end of the plot to the site of our house, in an area that is now an overgrown waste at the foot of a steep slope where we used to dump our stable manure.

With that information, certain things about the place make more sense. For one thing, the lane, which lies below a steep bank down from our field, acquires a decent (though ancient and tree-laden) stone wall only where the old cottage stood, which borders a flattish platform which, in retrospect, is just big enough for a humble stone dwelling, of which there now appears no trace, however. With far fewer trees at that time, it would have had a good view over the valley.

Additionally, I’ve been intrigued over the years by a slight dip at that end of the field, as if in the past livestock were accustomed to ambling up from the lane and eroding the path they took. This, of course, now makes complete sense as that was the “business end” of the smallholding.

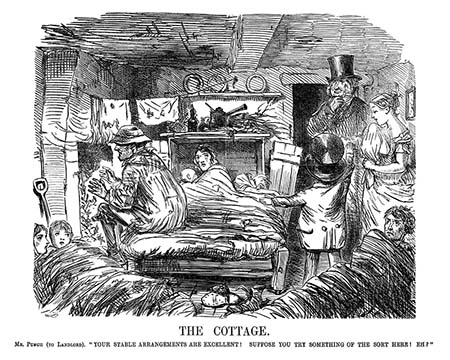

With the houses marked and a name to go on, I was able to do a bit of research in old census records and so on, and found that the following year the cottage was occupied by a mason named George Strawbridge, his wife, and six children, some of whose history I could trace in parish records. I was also able to find traces of the other nearby houses, tracks and gardens on the ground, including some ruins hidden in nearby woods that I’d not otherwise have known existed. That gave me an idea of what “our” cottage was like – pretty squalid for a poor and large family.

Perhaps that’s why the cottage has completely vanished from an Ordnance Survey map of 1888, though in conjunction with the tithe map that provides explanations for otherwise unexplained features of our landscape, such as dips and wobbles in the roads. Even the big oak tree on our boundary, which I’ve previously estimated to be about 160 years old, is marked on that. One one website it’s possible to overlay the 1888 map on to Google Earth for a direct comparison, revealing yet more history.

Perhaps that’s why the cottage has completely vanished from an Ordnance Survey map of 1888, though in conjunction with the tithe map that provides explanations for otherwise unexplained features of our landscape, such as dips and wobbles in the roads. Even the big oak tree on our boundary, which I’ve previously estimated to be about 160 years old, is marked on that. One one website it’s possible to overlay the 1888 map on to Google Earth for a direct comparison, revealing yet more history.

As always happens, one bit of research leads to another, and some reading drew my attention to the fact that in some areas (like mine) the field boundaries are pretty straight and rectangular, whereas further downhill they are completely irregular (see the plots below “Baggerton” on the map below). This turns out to be because the latter were enclosed during mediaeval times, whereas more marginal upland ground, like mine, was enclosed by Acts of Parliament after 1820. However, the parish bounday (forming the right border of the map) takes a straighter course which dates back to Saxon times, as does the existing ancient boundary hedge of holly and other species that marks it, just down the road, estimated by a species count to have been planted over a thousand years ago.

Armed with all that, I’m now able to say that my plot was probably part of the local mediaeval manor’s holdings, enclosed around 200 years ago with the very same banks that now form my boundaries, but fertile enough (unlike the “turbary” land to its left on the map), to be used for agriculture by an on-site cottager, though not sustainably. If I took the effort to clear and dig on the site of the cottage, I might even find some archaeology in the form of masonry, cheap pottery or clay pipes. It’s given me a great sense of continuity with our forbears.

I’ve written about this because it interests me, and might perhaps interest you. But it also occurs to me that it bears somewhat on questions of origins, in two separate areas. For almost all the detailed information I can gain from my spread, and its surrounding landscape, has to be interpreted from the existence of documents which explain it. I would never have suspected the site of an ancient house simply from a stone retaining wall.

If I’d even noticed that fields formed two patterns – regular or irregular – how would I explain it apart from the knowledge of changes in mediaeval farming and the political background to later land enclosures? For all I would know, my hedges could have been constructed after World War 1 or date back originally to Roman times.

Only parish and census records bring the actual lives of the people back then into relief: I can track George Strawbridge’s family to events like the death of his abandoned wife as a pauper some years later. I can chat with our neighbour about how Isaac Lane moved to their place from ours.

Without written history, what exists in the landscape itself tells some fragments of the story – or rather, of many possible stories, depending on the power of imagination. We need to remember that limitation in any account of origins. Archaeology, it is said, is the study of the rubbish history leaves behind – but even that forgets that most of that rubbish never even gets found. So when people complain about the lack of archaeological evidence for the Bible accounts, I will remember that, here in Devonshire, it’s the written records that explain the archaeology, and not vice-versa.

In the case of biological origins, there is of course no written history outside what we might glean from inspired Scripture – and in that case, biological history is not its subject matter, as I (like others) have often been at pains to point out. To construct a “history of the world” from the traces left in fossils or deduced from existing genomes is akin to reconstructing the history of England solely from Google Earth and walking round the country lanes or digging the garden.

At best it’s prone, in the very nature of things, to error.