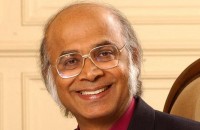

It was interesting, and not totally surprising, to hear that Bishop Michael Nazir-Ali, the former Bishop of Rochester and one-time candidate for the Anglican Primacy, has given up on the Church of England and defected to Rome. His reason, as you probably guessed, is the liberal wokeness of the present C of E, and the desire to be in a church which clearly teaches the faithful the apostolic doctrine rather than fashionable intersectionality and environmentalism.

As in the previous similar case of Gavin Ashenden, another Evangelical Anglican and former chaplain to the Queen who crossed the Tiber in 2019, there are difficult questions about the degree to which both men may have leapt from the frying-pan into the fire, given the same progressive agenda coming from the Vatican. For it is not that either has abandoned their Evangelical convictions, set in the context of historical Christianity, in favour of Papal Primacy, but rather that Anglicanism itself has lurched away from biblical truth more thoroughly than the Roman Catholics have.

As I have been observing for over two years now, the Church of England is far from alone in its capitulation to modern leftist doctrines: my own Baptist denomination, you will recall, allowed a pansexual to stand as its President in 2019, and its General Secretary has expressed sympathy for same-sex marriage as if it is only retrograde reactionary forces that are holding the denomination back from enlightenment. The alternative possibility, that what holds it back is the Holy Spirit operating among the faithful (see 2 Thessalonians 2:7), is seldom publicly expressed, if only because of self-censorship.

So, Dr Nazir-Ali’s move is yet another sign of the times rather than a bombshell. What may be more instructive is the character of the response even from those who sympathise with his move. Take for example this piece by Stephen Glover in the Mail.

A veteran journalist, Glover does not state his own religious views, but comes across as at least “sympathetic to the cause.” The piece is a fair and sympathetic appraisal of Nazir-Ali and his reasons for moving, and it is clear the writer agrees that it is the C of E that has really shifted, for he says that the bishop’s views would have been “familiar to Anglican worshippers half a century ago,” but are now unusual. He might also have added, given the move to Rome, that his views would have been familiar to Catholics 1500 years ago, or to Post-apostolic believers in the second century.

Glover is not ashamed to editorialise on Canterbury’s obsession (like every other Establishment institution now) with colonialism and climate change rather than its own rapid decline and worldwide persecution.

Of course there are historical events of which we should be rightly ashamed. What is so wearisome is the preoccupation with supposed misdeeds in the distant past, and the constant self-flagellation, when there are so many challenges and problems in our own time.

He could have mentioned, though perhaps significantly doesn’t, the lack of preoccupation with the gospel that saves lost souls. Indeed, to me the tone of the article actually contributes to what is wrong in the churches even as it appears to recognise and contest it in its support for Dr Nazir-Ali. See how Glover employs the argument that you have to admire the bishop, even if he’s a bit of a fanatic:

One doesn’t have to agree with every aspect of Dr Nazir-Ali’s opinions – and some Anglicans, let alone people of other denominations and non-believers, won’t.

Like the Roman Catholic Church he is joining, he is robustly opposed to abortion.

Nor has he been supportive of celibate homosexual priests working in the Church of England, or of same-sex marriages taking place in church. Though still not permitted, it seems likely they soon will be…

…Whatever one may think of his particular views, I find it impossible not to admire Dr Nazir-Ali for the rigour of his thought, and for his courage in speaking out in defiance of fashionable opinion.

Do you see a slight shift from what one might easily take as a simple message that we can agree that Anglicanism is in decline, but that at least one prominent member is taking a stand? The passages quoted above suggest that what Glover actually most admires is the generic courage of a man willing to stand up for his principles, rather than those Christian principles themselves. “Reasonable Christians” may well, he accepts, take issue with Nazir-Ali’s more extreme views.

But where did “reasonable Christians” get their reasonableness from? Glover seems not to have realised that the issues of abortion, homosexual priests and same-sex marriage are fruits of exactly the same progressivist roots as the anti-colonialism and climate-religion he accepts to be interlopers in the church’s agenda.

The whole programme of subversion of our social and moral fabric, whether you attribute it to a deliberate cultural-Marxist agenda or something less humanly organised, depends on disguising the real agenda under deceptive reasonableness. The true aim, since Marx, has always been the reformulation of the world along socialist lines, together with the abolition of both family and Church, but always under the guise of raising compassion, equality and justice above the inadequate standards taught by those bourgeois institutions. Whether Marx was a product of Enlightenment anti-biblical liberalism, or rather informed it (or both), both have similar ideological roots, and similar spiritual roots.

Those humanitarians protesting against nuclear bombs in the 1960s (and then against nuclear power) had no idea to what extent their movement was infiltrated by Soviet communists with no interest in peace, but only in the triumph of world Communism. Nowadays (and so more controversially), in the same way those swayed into demonstrating against racist police brutality simply miss not only the true political origins and agenda of the BLM movement, but are even blinded to the way they have been cynically manipulated by false narratives to elicit their compassion.

There are certainly those consciously seeking to destroy the Church by subverting its doctrine, but there are far more whose doctrinal principles, already subverted, will now inevitably lead them on the same trajectory. The first step, for example, for the political activists selling the environmental gospel is to disguise the principle of re-inventing society as the principle of “Saving the Planet.” Once the latter becomes their principle, the masses will carry through the activists’ agenda as the only reasonable course. Doctrinally, they will have been shown that we should preserve God’s creation, but kept from the understanding that God is quite able to preserve it actively himself, and calls us to the more humble task of living justly as he does so.

When, back in 2015, I first began to realise how the otherwise mysterious shift in public perceptions of homosexuality was a direct product of sustained propaganda (which I explored here) it became clear that one’s moral sensibilities may be strong, yet ill-grounded. Glover ought to have been asking himself (if he wasn’t simply being mealy-mouthed to avoid criticism) just why he doesn’t “agree with every one of Dr Nazir-Ali’s opinions.”

The clues would have been clear from what his own article subsequently finds to admire about the bishop: “the rigour of his thought.” Nazir-Ali’s strength is not in being a courageous bigot, but in being faithful to a consistent principle for arriving at Christian truth. That principle, of course, is the eternal teaching of Christ, who is “the same yesterday, today and forever,” which is recorded in the inspired word of Scripture. It is this principle that has been relativised or even abandoned, by the Anglican hierarchy although it is prominent in the articles of their establishment:

Holy Scripture containeth all things necessary to salvation: so that whatever is not read therein, nor may be proved thereby, is not to be required of any man, that it should be believed as an article of the Faith, or be thought necessary or requisite for salvation.

Courage is a virtue, but only if employed in a virtuous cause. Michael Nazir-Ali is courageous, yes, but that is incidental to what matters about his defection. The real issue is his decision to be faithful to a worldview in which Christ is present in his written Word, through the Holy Spirit who inspired it and who interprets it to the believer.

That faith always has been, and always will be, counter-cultural. It stands against fashionable identity-Marxism and it stands against anthropocentric environmental hubris. But it also stands against liberal reasonableness, and to many that is the greater stumbling-block. How many non-Christian allies in the culture wars have come out in recognition that, in the end, only Christianity stands against the darkness, and yet remain on the fringe because the gospel stands against their own chosen lifestyles?

But in the end, either Christ is Lord, or Satan is:

We know that we are children of God, and that the whole world is under the control of the evil one. (1 John 5:19)

Written beautifully, Jon.

Nature, like Satan, deplores a vacuum, and rushes in to fill it. The onus today, yesterday and tomorrow, is on those who stand under Logos, to stand by Logos. Anti-Logos (Satan, or “Polemos”) is always busy doing its thing.

Let us pray that those who stand under Logos soon learn to distinguish the light from the one who poses as an angel of light.