Back in 2015 I wrote about Jorge Luis Borge’s fantastical “Infinite Library.” Read my post to see how Borges envisaged it, and why it proved useless to imaginary readers free to browse its galleries, but unable to gain any wisdom from it. I guess the nearest real-world equivalents are legal-deposit libraries like the Cambridge University Library, housing every book published in Britain since 1662.

The U.L. is now in the news because of an apparent attempt to “help” readers avoid the problems of the Infinite Library by, in some as yet unspecified way, flagging up “problematic” books. Frank Furedi does a piece on it here, so I won’t go into detail, but one paragraph from Furedi’s piece should cover the basics:

The Telegraph reported earlier this month that Cambridge University Library sent a memo to the librarians in Cambridge’s 31 colleges, telling them: ‘We would like to hear from colleagues across Cambridge about any books you have had flagged to you as problematic (for any reason, not just in connection with decolonisation issues), so that we can compile a list of examples on the Cambridge Librarians intranet and think the problem through in more detail on the basis of that list.’

Borges had no concept that the Infinite Library management would direct its readers what to read.

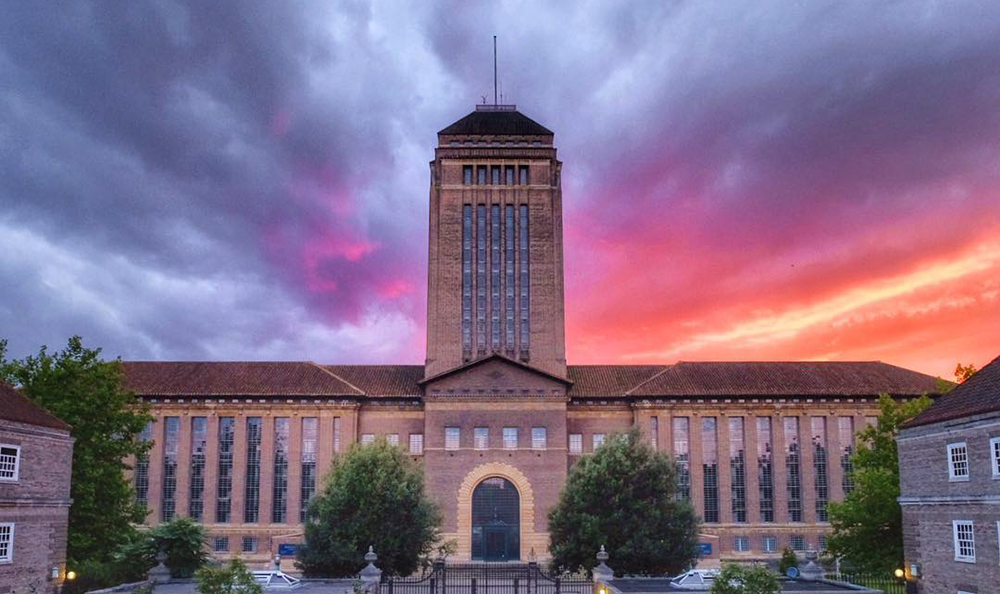

I happen to be a member of Cambridge University Library, though I’ve not used it since my “official” theology studies around 25 years ago. My last visit was a memorably truncated session on Victorian Christianity, to which I arrived to find my pile of requested books already on the desk, ordered from afar via the Internet – which still seems a wondrous thing to me. Unfortunately, I’d failed to clock that I would be on call for the GP co-operative the night before, and having been up all night and driven fifty miles to Cambridge, I only made it through to lunchtime before I became incapable of making sense of the text. I might add that for biblical studies, Tyndale House Library is far superior.

But my first visit to the library, as an undergraduate back in 1971, was quite overwhelming: imagine a cathedral jammed to the rafters with books. I wondered (in those pre-internet times) at how I could, like Borges’s students, gain access to anything I chose to feed on, quite apart from the research paper whose reference my supervisor had scribbled on a piece of paper for my immediate edification. Consequently I couldn’t resist searching the index for books by “Garvey,” and to my delight my first hit was “Garvey and Garveyism.” It was as cool a moment (for someone with a surname rare in England) as seeing Manfred Mann’s Mighty Garvey album in my local record shop.

I had never heard of Marcus Garvey, or his “Back to Africa” movement, and I didn’t read the book (I had actual work to do!), but over the years that first acquaintance with “Garveyism” has enabled me to glean information from odd references, and to make some personal judgements as to whether it has any merits. I have had no problem finding out that some would judge Garvey “problematic” in the contemporary sense, which would obviously have more significance to me were I black rather than just a namesake. To quote the near-infinite library Wikipedia:

Garvey was a controversial figure. Some in the African diasporic community regarded him as a pretentious demagogue and they were highly critical of his collaboration with white supremacists, his violent rhetoric and his prejudice against mixed-race people and Jews. He received praise for encouraging a sense of pride and self-worth among Africans and the African diaspora amid widespread poverty, discrimination and colonialism. In Jamaica he is widely regarded as a national hero. His ideas exerted a considerable influence on such movements as Rastafari, the Nation of Islam and the Black Power Movement.

Now, if I were a Jamaican studying sociology in Cambridge, to whom Marcus Garvey is a hero, how would it help me if (in some way) the University Library flagged up Garvey and Garveyism as problematic, because of its alleged links to the dreaded “white supremacism”? Without such a warning, reading intelligently, if I found anything in the book that tempered my hero-worship, I would modify my opinions of him accordingly. And if not, and the “problematic” issues are actually about the man rather than the writings I’m studying, then so what? Even if Garvey turned out to be Justin Trudeau’s ancestor in blackface, his ideas would either stand or fall by themselves.

So any kind of screening action taken by the U.L., from a warning sticker on the spine to omitting it from the index and putting it in the cellar, to burning it altogether, would simply bias my intellectual judgement for no gain. I could not even start the book without already expecting it to be of dubious merit, and since no book is perfect, the trigger-warning would focus my attention on the “problems,” probably blinding me to any useful ideas the censorious librarians had missed. Apparently this is now the real problem in studies of Literature, as students are channeled into searching for racism or colonialism in the author, rather than engaging with their shared humanity.

There has always been some informal poisoning of the literary well. For example, the Evangelicals from whom I learned the faith tended to dismiss Aquinas as anti-scientific and, well, Catholic. Even more censorious have been the biology teachers and authors who have dismissed Jean-Baptiste Lamarck as a pre-Darwinian fool, and Alfred Russel Wallace as an unscientific Spiritualist. But some of us have little problem questioning informal judgements, and I have gained much from reading all three of those thinkers, and more. If you want to see my conclusions, use the “search” function here.

It is more of an issue when such cultural warnings against wrong-think are official. It was bad enough to find, on visiting the Reformer John Knox’s house in Edinburgh, that culturally-conditioned labels actually put one off reading his work and identified him solely (and wrongly) as a misogynist for writing The Monstrous Regiment of Women (which would nowadays have been entitled, “Should Women be absolute Rulers of Nations? – a Scriptural survey on the complementary roles of the biological sexes”).

But it is a lot worse when, by whatever gentle means it may employ, a university library applies its own value-judgements to the books it contains. As soon as an academic library suggests what researchers ought to think, it ceases to be a library and becomes a mere propaganda organ. When it’s the size of a cathedral, it might be better used for storing furniture.

My last allusion relates to an anecdote that may amuse readers. Many years ago, “The Guv,” the inspirational leader of my Crusader Bible Class, a staunch non-conformist and, by trade, the owner of a furniture store, was with another leader, a staunch Anglican. They were looking out of the window at the new Guildford Cathedral (incidentally very similar to Cambridge UL in design!), which was slowly taking shape on Stag Hill.

“What a wonderful building,” The Guv mused.

The other, surprised at his unusual enthusiasm for church architecture, replied, “Do you really think so?”

“Yes,” replied the Guv. Just think how much furniture you could store in there.”