I thought it would be worth spending a few posts looking back on what has turned out to be a fruitful “research programme” on scientific and biblical origins over the last ten years for me, to see what problems have been resolved, and which, if any, remain unanswered.

Of course, it’s true to say that no solutions one finds to these questions will satisfy everybody: people totally convinced of one explanation of Scripture will reject any others out of hand, whereas the skeptic convinced that the Bible is pious fiction will reject any signs of accommodation between science and Scripture on principle.

By way of introduction, let me recount how I first began this, even a year or so before The Hump of the Camel took its first tentative infant steps (what is the correct term for a baby dromedary?).

I took early retirement from medicine when the opportunity arose suddenly, intending to do some serious writing, after experience in both medical and Christian journalism. But I actually hadn’t thought out what to write about.

Nevertheless my first project was ready to go: a series of features for the magazine on whose editorial board I then served, forming a series called Unsystematic Theology. The idea was to take a series of the theological subjects that seemed most relevant to contemporary Christians, without attempting to be exhaustive. So I spent the first month or so of my post-career work on it, and sent the whole series off to my editor as a job lot.

As the months went by I began to wonder why the first part hadn’t appeared, whilst my regular columns on current affairs turned up as usual. After about a year, I asked about it and got an apologetic phone call from the editor. It turned out he’d been sitting on the series because of the first part, which logically enough was on the doctrine of creation. And the reason was that, in his view, the magazine had an unwritten policy in support of young earth creationism, and I had mentioned that some version of evolution did not necessarily clash with Genesis 1.

The absurd thing was that the whole piece was written to avoid the tired old debates of Creationism versus Evolutionism, and to view the biblical doctrine of creation as a rich and multi-faceted truth about God, with implications for every part of life.

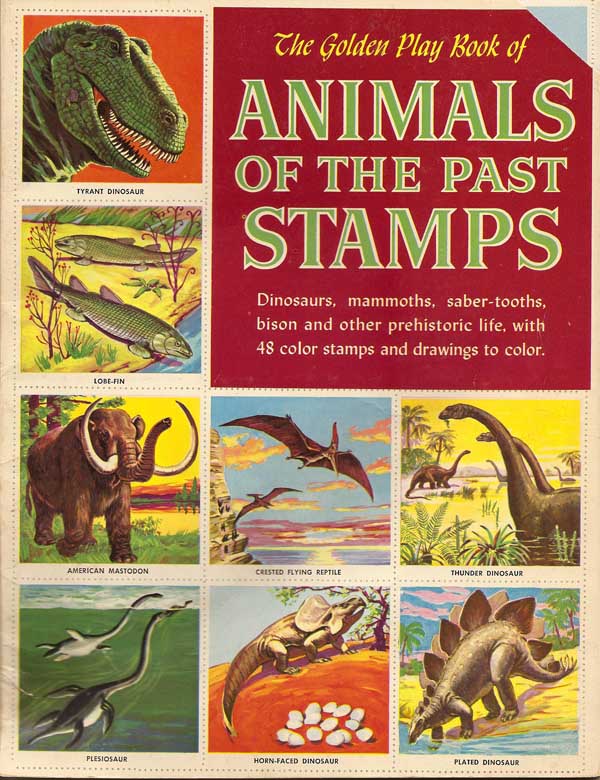

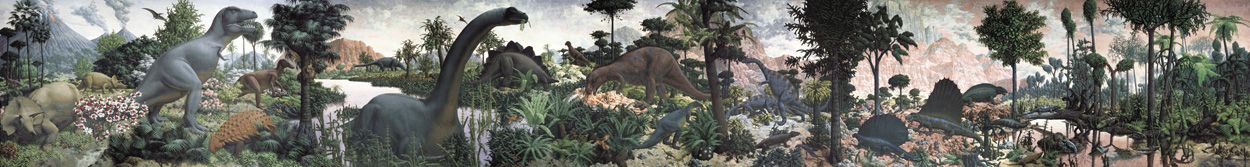

Anyway, the editor, though he respected both me my work, wouldn’t change his mind, and I wouldn’t back down, and so the magazine and I parted company after fifteen years. But the episode got me wondering again about the link between the historical sciences and the Bible that had been part of my life since I was six (and discovered dinosaurs and evolution), particularly after I was converted at the age of 13 at the height of my ambition to study zoology.

Although I went through various stages of opinion over the years, “faith science conflict” was never a personal problem for me. I was both interested and well-grounded in the sciences dealing with the past, and (to be frank) the world didn’t make much sense without taking them seriously – one can only take “appearance of age” arguments so far before they become encumbrances rather than explanations.

On the other hand, in 1971 I had a vivid encounter with the Holy Spirit, which transformed my relationship to Scripture, convincing me that it is the living word of God (as it were, Christ himself on paper). Before, I’d believed the Bible because it was part of the faith I’d embraced – afterwards, and ever since, I believe it because it’s part of me. To quote something from one of Os Guinness’s books: “I knew the Bible was true, but I didn’t know it was that true!”

The net effect was to make me comfortable to live with the apparent tensions between science and the Bible. But I was aware that the stakes were far higher for others, whereas for me it was a matter of consolidating two undoubted truths. In particular, I kept remembering a visit from one of the members of the youth group I’d once led, who came round with a friend also struggling to accept biblical faith in the light of A-level science. I think, given what I knew then, I made a reasonable fist of pointing them to Jesus first, and seeking the answers in the light of his wisdom.

But my pique at having an entire series of articles rejected over the issue resolved me to try, if I could, to find some answers. I did, after all, have training both in the biological sciences and in theology, and an active interest in the matter going back for what is now sixty years. And that’s how I found myself interacting at BioLogos, agreeing to a couple of suggestions that I should start a blog, and to the urgings of others to write what have become two books, God’s Good Earth and The Generations of Heaven and Earth.

I see that my autobiographical self-indulgence has left me little space to address the actual issues here, so I will stop today by listing what seem to me the problems I brought with me as I looked for solutions consistent both with our knowledge of nature and theological orthodoxy. I’ll deal with them in subsequent posts – and meanwhile, if you can think of any common and important questions I missed, please mention them in the comments.

Common problems on origins:

- 6 Day recent creation

- Old earth with death, carnivores and natural evils – creation “groaning” for 13bn years?

- Creation with no need for a Creator

- The impossibility of Adam (and the existence of early humans and intelligent precursors)

- Mankind as ruler of earth coming late to the party.

- Worldwide flood

- The natural evolution of mankind with consciousness, spirit and eternal life

- The origin of spiritual evil (Satan before the Fall)

Pingback: Jon Garvey: A Biblical Theology of People Outside the Garden

Hi Jon,

You and I had a brief encounter on Joshua’s Peaceful Science forum a while back. The article on your latest book and some other stuff you talk about on your blog piqued my interest.

I was excited when I first found Joshua’s forum. I wanted to discuss these ideas in depth with people with expertise in the relevant fields. Really dig in and explore. Up to that point I had met with such resistance to the idea of pre-Adam humans, or the very idea that Adam was an actual historical figure, that the conversation was never allowed to flourish. I thought that it would be different in the PS community since that particular hurdle wouldn’t be an issue, but was taken aback by how much resistance I found there as well.

You mentioned Joshua’s intention for people of many persuasions to apply the paradigm as they see fit. I agree with this approach, yet this seems to be the wall I kept running into. Specifically in regards to Romans 5.

You and I seem to be very much on the same page in a lot of aspects, so I feel you’ll likely see the issue I was attempting to address. This also butts up against one of the ‘Common problems of origins’ that you listed, specifically ‘the origin of spiritual evil’.

According to Rom5, as you know, sin entered the world through Adam. A significant focus in Joshua’s concept was to make it clear that pre-Adam humans were not lesser or different in any way than those who came after. And I certainly understand the concern there.

The idea I was floating is that what made Adam significant, and why the story began right there with him, was because he and Eve were the introduction of free will into the natural world. A world that had up to that point been completely in compliance with God’s will, including a fully populated planet of humans.

So, basically, the capability of evil was introduced through the introduction of free will. The capability to behave contrary to God’s will. Something akin to behaving contrary to gravity.

This, I think, is an important distinction between humans before Adam and those who came after. This is what makes Adam and the story of the bible significant, what makes Paul’s statements in Rom5 true, and what made God’s direct intertaction with humanity during this period necessary.

And recognizing this, as I was attempting to illustrate, allows us to pinpoint these events in human history. A behavioral change that can be seen in the archaeological data starting right where/when Genesis is set and spreading all throughout the world from there. A change significant enough to completely transform how humans live and operate.

Anyway, there are a number of things you said on your blog that get into the theological consistencies with this kind of scenario, and that’s exactly the kind of thing I was looking to explore when I originally found Joshua’s community.

If any of this interests you I’d like to hear your thoughts.

Hi again Jeremy, and welcome to the Hump.

The way I started working through a similar approach to that you describe was in Romans 2, where the internal law available to gentiles as well as Jews who have the law is described as “conscience.”

That word in Paul has a slightly different connotation from its common use now, in that we tend to view it as a matter of feeling – only loosely related to any absolute standard – whereas to Paul he’s considering it as an indicator of actual guilt as well as consciousness of it. Obviously there must be some link between the consciousness and shame of behaviour under conscience, and the accountability of free will. No will, no conscience.

On the other hand, it’s quite difficult to define “free will” as a hard endowment in an absolute sense. We know we have choices subjectively, and only doubt it from philosophical wranglings about the sovereignty of God or the determinism of matter. But imagining an intelligent being without such liberty is pretty hard.

Even my old labrador has free will enough to choose to continue investigating an interesting smell or come to my call (and his response varies with his mood). Even more so do the higher apes show evidence of choice: you, however, are placing it specifically in the moral sphere, and indeed in relation to the moral will of God.

That, I think, is actually quite hard to pin down in the archaeological or historical record, though as a matter of biblical deduction, if Adam’s sin led to the kind of degeneracy that Romans 1 describes, I’m open to looking for an escalation of detectable things like increased brutality. We at least find evidence for organised warfare and apparent deliberate mutilation as we get to the Neolithic, though the earliest example I could find is rather earlier at 15K BP. Alleged cases of deliberate homicide from the palaeolithic are harder to assess – an arrow in the spine might be aggression, or might be a hunting accident.

But a bigger problem, to me, is that in order to express your free will as a negation of God’s will, you have to know God’s will – and that’s the definition the Bible places on sin, rather than the rather facile assumption made by many theistic evolutionists that it’s “selfishness” (often blamed irrationally on “selfish” evolution).

So the existence of free will in Adam is assumed by his receiving a command, whether that freedom originated in him or not. But only the command itself – ie personal revelation – made disobedience possible.

And so I’m inclined to place the significance of Adam not in the new endowment of free will (or in any other human attribute, come to that), but in the call into relationship with God, which gives the possibility (given our experience of will) for willing obedience and trust, or rebellion.

That is what explains Joshua’s cryptic statements that those outside the garden “sinned”: I think he means they may well have acted in ways that are not in accordance with what God has now revealed as his law, but only because he had not revealed it. My own spin is that they acted from God-given nature without personal knowledge: Adam, however, was intended for higher things.

I should clarify what I mean when I say free will. That was one of the points of contention on Joshua’s site.

I like your dog analogy. I would call those instincts that all dogs have done since there have been dogs. All behaviors and choices are made in the interest of the original commands given to all living things; be fruitful, increase in number … He’s thriving and surviving and doing what is in his natural will. He behaves just as all life behaves.

Free will is when we stop living in harmony with nature, and begin instead bending it to our will. Your dog behaves just exactly like everyone else’s dog. A dog is a dog. A lion is a lion. They live and behave as they always have.

But humans took a dramatic left turn right here. In the middle of the desert of all places. Humans, just as intelligent and capable of anything as any of the others, lived all across the planet in a wide range of environments and conditions. Yet civilization sprang up in the middle of a desert.

They started irrigating and farming. First in Sumer. A place, as you’ll find in the archaeological record, was a culture that was one of increasingly polarized social stratification and decreasing egalitarianism.

Up until that point humanity all across the world had been egalitarian by all appearances. But starting right from the beginning, Sumer proved to be unlike any other human culture. Farming was already being practiced elsewhere, in largely populated organized communities. Yet none of the behavior changes that happened in Sumer happened there. And Sumer also has an impressive number of firsts when it comes to human inventions. Another thing that sets them apart from other farming communities.

This is the evidence of free will. Humans beginning to deviate from the natural order as they had lived for tens of thousands of years to become non-egalitarian/ male-dominant civlization builders. First in Sumer, then after Babel, in Egypt, the Indus Valley, eventually Greeks and Romans. The families of Adam/Noah introducing free will everywhere they went.

Also, a clarification. I don’t think free will is a genetically spread capability, or something that others are incapable of. Just like it’s illustrated in the garden story, all it really takes is a nudge. A suggestion. Start questioning. Why? Why not? Why not me? So, I think free will can take hold purely through influence and interaction.

I should also clarify that not all done through free will is evil. It just makes evil possible.

Re: “express your free will as a negation of God’s will”

Free will isn’t the negation of God’s will. It’s an individual will apart from God’s will. Independent. Sin is when you express your free will as a negation of God’s will/law that you’re aware of. Like it says, judgement is based on your understanding.

There are a couple of books that trace this behavior change I’m speaking of. In one of those, The Fall by Steve Taylor, he refers to it as the emergence of the modern human ego, which I think is a good way to describe it.

Yuh – like I say, pinning down the evils of civilisation to a direct fruit of free will (in a scientific kind of way) is difficult because we can’t say very easily that such choices were not being made before farming/civilisation, and it might just be that civilisation gave a wider range of choices.

For example, it’s increasingly realised what technological inventiveness was involved in the various stone tool cultures even back to Neanderthals: knapping a decent flint tool requires as much clever choice as learning to forge bronze – but the hunter-gatherer doesn’t have the infrastructure to move on to the latter.

Clearly, though, people as we know them have the ability to choose between following God-given nature and not doing so, and that’s uniquely human. I’d say that the danger of defining free ill as “the individual will apart from God’s will” is that it begins to make sin look definitionally inevitable, that is (like the evolutionary creationists tend to say) we had no option but to sin once God gave us liberty of will.

However, Jesus’s liberty, even as the eternal Son before the Incarnation, was certainly no less than ours, yet he always chose to do his Father’s will: he used his free will to choose dependence. And of course traditional Christian doctrine is that we find true freedom in obedience: the will is only truly free when not in bondage to sin (a paradox).

Augustine, who thought more about the nature of the will than nearly anyone, dealt with this freedom/bondage matter extensively, which is why both Luther and Calvin, his followers, wrote on the bondage of the will through sin and its liberation in Christ.

So, Adam (however created) was intended for, and capable of, freely-willed obedience to rule the earth entirely in accordance with God’s plans: responsibility was God’s gift for the blessing of kingship. (I leave aside here the knotty matter of God’s knowing the end from the beginning, and anticipating Adam’s sin – my point is that disobedience was not a design fault owing to an inbuilt desire for autonomy: and hence when we lose our sin, we do not lose freedom, but gain it).

Maybe we should set aside the specific characteristics of free will for now and just focus on identifying a shift in human behavior that reveals what’s described as accurate.

We have an approximate location and even a rough timeline given the clues of the text. I don’t think this being the same time/place as the birth of civilization is a coincidence.

Re: “we can’t say very easily that such choices were not being made before farming/civilisation, and it might just be that civilisation gave a wider range of choices.”

I believe we can. Like I was describing yesterday. Sumer was not the first largely populated farming culture. There were cultures in northern Mesopotamia/Turkey with populations in the tens of thousands that existed for centuries that predate Sumer(5500 BC).

– Catal Huyuk (7,500 to 5,700 BC)

– Lepenski Vir settlement (dating back to 7,000 BC) which gave way to …

– Vinča-Turdaș culture (5,000-4,500 BC)

The conditions in Sumer were not unique. If anything it was more unlikely to happen there because it was in such an arid climate. In northern mesopotamia farming was much easier.

But none of those previous cultures experienced the progressions of Sumer. All of the above cultures remained egalitarian and none exhibited any sort of class stratification. So this, to me, shows it wasn’t civilization that opened up the range of choices.

That is a common argument, that farming made for higher density in population and increased interaction and sharing of ideas. That it was a natural progression from that to civilization.

But I feel there’s ample evidence to show that the progression made in Sumer, Egypt, the Indus Valley, was not a natural progression. It’s evidence of a significant change in the people of these places. The result of the events of Genesis and the impact it had on humanity. It caused the shift that turned humanity into civilization builders.

And yes, I think sin is inevitable with free will. Wielding a free will responsibly with no guidance takes a wisdom that we don’t have. We were handed the keys to the car, steering wheel in hand, but there’s no map and no road signs. That’s what I think this life is. Beings with their own free minds and individual identifies for all eternity is the ultimate goal. An entire lifetime of human existence to draw on is just the kind of knowledge base one would need to do so.

Free will in essence makes us creators. This universe consists of things made by God and things made by us. It’s a huge responsibility.

The element of free will in the story being told is, I think, an important one. To understand that from the moment Adam/Eve fell, there was an element present on Earth not in God’s control. Up until this point all the universe behaved according to His will.

As the story of Abraham and Isaac illustrates, God can’t anticipate what we’ll do. It’s truly a will free of His. By design. Even with the benefit of seeing all past/present/future, if Abraham is never put in the position to make the decision, God cannot know what that decision would be. Just as God could not know without actually doing it what would become of creating free will. This is why I think God was so ‘hands on’ for that portion of human history and no other.

It’s an important dynamic of the story that I feel is crucial to truly understanding what’s being described.

Well, here’s where the rubber hits the road in terms of profound theological disagreement. I wouldn’t disagree that the fact that the early Genesis narratives show clear relationships with Sumerian literature, and that many cultural indicators put it in that setting, makes the rise of that culture suspiciously like the results of Adam’s sin.

There’s still the caveat that the very reason we know about their social structures is that they invented writing: the other cultures we have to speculate on from archaeology, and that tends to turn up surprises that overturn what we like to think those cultures were like.

But since that is speculative territory, it’s no big deal to me. Where I do take issue with you is here:

You’re concluding the moral/theological state of mankind from an assumption that Sumerian archaeology shows (a) the race was endowed with free will and (b) that it had no guidance as to how to use it. That is actually almost the exact opposite of what the Genesis narrative says, which is that the first of “us,” Adam and Eve, were taken into the direct presence of God to be educated by him, and that they had a very clear roadmap, with a command that was the key to how the relationship would develop.

The Fall is the story of how we abandoned that program and put ourselves in the situation of having no roadmap, contrary to God’s stated will. Indeed, it was only as judgement that Adam was sent back out into the world, and (on the line we’ve been taking) that the evils of civilization emerged. But it never needed to be so.

Yet God never abandoned guiding Adam’s descendants, even before the call of Abraham, but expressly so afterwards: the re-establishment of lost relationship – emphatically not the development of ultimate autonomy – is the whole business of the Bible thenceforward. And the “USP” of the gospel of Christ, from the prophets onwards, is that God writes his law in our hearts, so that we desire what he desires, and in the end the whole creation is united in and by Christ. There is no eschatological hope of eternal autonomy – unless you count the state of damnation – that was the whole problem that Jesus came to remedy.

The fly in the ointment here is the other main character of the story – the serpent, clearly from other Scriptures embodying or representing Satan. I’ve argued at Peaceful Science and here that the Serpent’s own rebellion against God arose from jealously of mankind, rather than (as in some trad. theology) before creation. But either way, the angelic being too has the freedom to go against God’s purposes – it seems to me harder to make that a new endowment within history.

Then again, the assumption that free will trumps God’s control is a dangerous one denied at numerous points of Scripture. Two of the most notable are, OT, where the malice of Joseph’s brothers was subsumed in the will of God to do good through Joseph (“You intended it for harm, but God intended it for blessing”; and, NT, where the apostles rejoice in prayer that the evil rulers who crucified Jesus did exactly what God had foreordained they would do. Such passages are explicit denials of the autonomy of free will.

This is the Open Theist position, which is a modern hyper-extrapolation of Arminianism. To say that God can see past, present, and future but not know Abraham’s decision is simply incoherent, which is why throughout theological history, until Socinus, I believe, the passage was never taken that way. As it happens, I did a rewrite of the Bible the first time I heard someone tell me that low view of God’s omniscience in the Abraham narrative. It’s on my website here, and it shows that the entire OT metanarrative becomes simply ludicrous if we accept your view.

Yes, writing. Another indicator of free will. In Sumer, writing came about from a need to keep track of who owns what and who is owed what. Accounting. In ‘unfallen’ cultures, like the Aborigines for example, individual ownership of possessions is a completely alien concept. Everything belongs to the tribe. There’s no status of one over another. That’s where ‘fallen’ people are different. They’re not egalitarian. And egalitarian cultures have no need for writing.

Writing is a clue. That’s something that never happened in those earlier farming communities, yet happened at least 3 separate times in a relatively small region and in a very short amount of time. Both in Egypt and the Indus Valley, they also invented writing, totally independent of one another. And they both came about roughly the same amount of time after Sumer that the flood/Babel happened after Adam’s creation. 1500+ years.

Re: ‘But either way, the angelic being too has the freedom to go against God’s purposes – it seems to me harder to make that a new endowment within history.”

I don’t think he does. Take the story of Job. Satan had to have God’s permission. I think the serpent in Genesis was doing his job. The garden scenario was setup just like a controlled experiment. One rule. What the serpent did was a necessary step in that scenario.

Re: Abraham/Isaac

The whole story of the Israelites is God’s direct involvement to ensure the outcome He promised. It’s not like before in creation, He spoke and it became. Like the Gen1 humans. They were commanded to be fruitful and multiply and fill and subdue the Earth. This is exactly what homo sapiens did. Over the course of 1000s of generations. But with Adam, one command, broken, generation 1.

Time, past/present/future, is all simultaneous to God. He doesn’t have to wait a span of time to see an outcome. As long as it’s in the picture He can see it. All that’s God’s creation, it behaves exactly according to His will. No surprises.

Free will’s significance cannot be overstated. Without it, heaven is a bunch of drones. Beings who only behave according to God’s will. Free will is companionship.

I really appreciate it, Jon. My theological knowledge is admittedly lacking. It’s difficult to have discussions with those who are experts without too quickly being dismissed a heretic.

Yes, there are numerous examples of God working within the environment of human free will. Orchestrating outcomes among the chaos. It really underlines what an enormous undertaking this all was.

I should also note the decreasing egalitarianism and social stratification in the early phases of Sumer, the Ubaid culture, were determined primarily from grave goods.

That won’t run, I’m afraid – the story itself has God punish the serpent for what it has done. That does not preclude God’s oversight of events from the eternal perspective (remember that Christ is “the Lamb slain before the creation of the world”), but it does preclude Satan acting in concert with God’s purposes as a non-volitional agent. And if Satan sinned, angels too have free will and the theory teeters.

But that is not the only evidence from Scripture: in 2 Peter it says God punished the angels “when they sinned,” and Jesus himself referred to the fire prepared for “the devil and his angels” as punishment. Daniel refers to a war in heaven, and both these last themes are expanded in Revelation 20. Etc, etc.

The example of Job does not contradict that – one needs to understand it in terms of what you might call the “politics of the spiritual realm,” at least as described for our limitations in the Bible, which I discuss in my book The Generations of Heaven and Earth, but which make no sense apart from Satan as a volitional agent with his own agenda.

I suggest, more generally, that you do some reading to escape from the modern mindset that “free will” is the opposite of “robotic.” Though it’s not that modern, being one of the errors into which Pelagius fell back in the day. In fact, as I’ve already said in this discussion, free will in biblical terms is the ability to participate in the freedom of God himself, which is always just, loving, and so on. It is in a limited, creaturely, sense to share in God’s higher nature, and so Paul is able to say “We have the mind of Christ.”

Jesus is in that, as in all things, the absolute exemplar for our own humanity: read John’s gospel for how many instances there are like “Truly, truly, I tell you, the Son can do nothing by Himself, unless He sees the Father doing it”; “I do nothing on my own, but speak just what the Father has taught me”; “I always do what pleases him.” And of course he prayed, “Thy will, not mine, be done,” in the garden. This, remember, is the Eternal Son, whose very willingness to take on humanity was to comply with the will of the Father (Hebrews 10: 5-7, quoting Psalm 40).

God’s involvement in history is not merely the strategic manipulation of other wills (that too is one of Open Theism’s innovations) – it is inherent in his nature as God, for human will and freedom can only subsist within his own will. And that is why God not only acts so positively throughout the biblical narrative – he also claims the same initiatives in the non-biblical world, and even the daily operations of nature. “In him we live, and move, and have our being.” It’s so much richer than the chess-playing God seeking somehow to outwit wills like his – or, in some recent theologies, declining to do so because it would be interfering in their free will, which under that crude model of the will it is.

The ability to rebel is real, but it is an aberration of the will (hence Luther’s “the Bondage of the Will,” and Jesus’s “Whoever commits sin is a slave to sin… So if the Son sets you free, you will be free indeed.” He says this in the very context of his stating his absolute obedience to the Father’s will. We have badly understood free will because we have underestimated God, just as Eve did in the garden when the serpent convinced her that God’s prohibition was an attempt to assert his interests over hers (Gen 3:5).

My experience of 55 years as a believer: the more I find myself within God’s will, the more freedom I experience. And that is because the wonder of human free will was created to be enjoyed within the infinitude of God, not in contradistinction to it.

Yes, exactly. Like the test of Abraham. Would his will outway God’s? I think about it like this. Eternity. Millions of individuals. Interacting.

Like the road system. We are each free to go where ever we want. But to keep everyone from barreling into each other there are rules. And you have to be licensed. You have to agree to adhere to those rules and to submit to the authority of the roads. There has to be order, and order requires an authority.

The body is made up of billions of individual components that all operate according to the DNA code of the body. Because everything complies with the code of the body, all parts act as a single unit. This is akin to the universe as a body and natural law as the DNA.

Free will would be like if you could give each cell in your body the choice whether or not to conform to the code of the body. Those who do not conform and comply become a danger, a potentially destructive element, in the system of the body.

The natural world behaves in predictable ways. Each element behaving exactly according to natural law. We humans are the one exception to that rule. We’re the only components of God’s creation who don’t behave exactly as God wills/natural law. For A/E to have eaten from that tree would be like them not adhering to gravity.

I don’t think of the consequences of Adam/Eve/Serpent’s actions as punishment. God’s simply explaining the results of their actions. The change they introduced would result in these things. It’s like stepping off of a cliff. The result is you will fall no matter what. Whether you were stepping off of the cliff with permission or not.

Like Eve’s consequence that she’d be subserviant. Male dominance is another characteristic that didn’t rise up in human behavior until Sumer. It’s not a punishment so much as it’s a result of their actions.

Also, I don’t know, the chess-playing God is pretty rich. I want to lay out a view I hold that better defines how I’m looking at this.

God’s involvement right from the onset appears to be intended to breed Jesus from Adam’s line, working in an environment of free will not entirely in His control.

God chooses Noah and his family because God favored him and wipes out the rest as He observes some negative characteristics that have evolved. The flood isolates Noah and his family, as a breeder would do.

Later down the line a few generations, after testing his will, God promises to make Abraham’s descendants many. He’s choosing who to breed through based on desired characteristics, as a breeder would.

Then, the Israelites. He sets them up in Egypt where they’re isolated and together. But then, when He hears their cries, He frees them and isolates them in the wilderness. And He gives them rules controlling what they’re eating and who they’re intermingling with. As a breeder would commonly do.

This is the line that Jesus came from. The personification of the characteristics that God was initially testing for realized in a human. Ultimately correcting the course from the onset. The second Adam.

Jeremy

It always interest me when someone takes the Bible as a “given” authority (assuming, in this case, the historicity of its events), but then investigates its meaning as thy might do with inanimate nature.

Nature, even if created by God, simply exists, and we make sense of its phenomena as best we can: that’s what science in the broadest sense is, and the conclusions are very different depending on what phenomena you choose as significant, and what metaphysics you apply to them. The physical world doesn’t tell us what it means.

But the Bible, like all books, was written by people with a purpose in mind: they intended us to follow their thoughts to the conclusions they wished us to draw. And hence, contrary to your explanation, the consequences of sin (and specifically the sin in the garden) are described in terms of punishment, judgement, wrath and the like, and not merely as “natural consequences.”

So the question I have to ask myself is whether Moses, or Isaiah, or Jesus, or Paul, or Peter, would have intended that we understand their narrative in terms of the necessity of free will, or the actions of a prize-stock breeder deity, or whether they had a different “metanarrative” in mind.

As far as I can see, your core ideas are not without precedent – there’s seldom anything new under the sun. And so (as I discuss in God’s Good Earth) in Renaissance humanism Adam became re-cast from the archetypal traitor to be a hero of autonomy and initiative over an oppressive, even insecure, God – until the rediscovery of the Prometheus myth gave them a better fit to their anthropocentrism.

Their pattern of thought bounced around down the ages through Deism, the Enlightenment and, arguably, into Postmodernism’s “post-truth” age. But it was always radically opposed by those who saw, in Jesus, the need for God to be at the centre, not us. In my view, it is their standpoint, not the others, who match the attitude of the biblical authors – and we are reading their stories, after all.

The historical core of this is not Eden, but the cross and the empty tomb. I place my faith in Paul’s summary of the ultimate goal of these unique events, in 1 Corinthians 15:

“So that God may be all in all.”

Yes, I agree there’s a purpose in it. The way it begins with describing how this God spoke the universe into existence, then in the very first story, illustrates God creating something that then disobeys his command. This contrast seems deliberate.

Then the whole story from there commonly involves human behavior as a theme. People who do and do not obey God.

My approach is simply to re-assess in light of modern knowledge. I definitely don’t take the bible as a “given” authority. I have a deep distrust of human involvement, of which there’s a considerable amount, especially the later the books are written.

This is why these early books are so important to me. These are the stories all the rest of it was based on. A lot of it seems was just as big a mystery to them as to us. Take the book of Enoch. It reads like fan fiction.

But we today have more information to work with. More context to ground the stories being told and make them more clear.

In a way, the consequences of sin are a punishment. They are the consequences of choices made and actions taken. That’s what this world is. Immediate feedback. Everything we do in this life effects others around us. That’s why it seems to me the perfect environment to create something like free will.

Yes, I agree God is at the center. But this God’s intention and all of His efforts seem to be focused on creating and forging humanity. For the God of this seemingly infinite universe to focus so much attention on a rather small band of humans on what seems to be an insignificant planet seems telling.

But yes, from the fall on the primary focus was Jesus. A course correction to account for the fall that severed the link between humanity and God. A new priority to achieve the initial goal.

It’s not about conflicting with God’s will but rather learning to operate according to God’s will through our own volition. He doesn’t force it on us. He made it our choice.

That’s another clue regarding God’s omniscience in the existence of free will. The flood. God’s “regret” for making humans on the earth. This to me is a clear indicator that the behavior He observed in His creation was not fore-seen.

The Flood “regret” is another of the examples the Open Theists have picked up and focused on, like his “repentance” at having chosen King Saul and a few others. All these have always been known by orthodox theologians for ever, who have placed them in the wider context of God’s directly theological self-pronouncements about knowing the end from the beginning, making specific promises millennia in advance, directing the hearts of kings, raising up the Babylonians as his weapons, not repenting or changing his mind, etc, etc. They conclude that the only legitimate explanation is that it is impossible to speak of the transcendent God (still less talk with him) except using human metaphors.

A good example is your “But yes, from the fall on the primary focus was Jesus.” If that were true, it would still involve God’s control of the world’s history for thousands of years after Adam to prepare the ground for this one individual “just at the right time” (as Scripture says). One aberrant “free choice” from a drunken chariot-driver while the infant Jesus was playing in the street, and the entire plan fails.

But in fact, Jesus was not a reactive response to an unexpected fall. I have previously quoted Revelation’s “the Lamb slain from the foundation of the world,” but Paul too writes:

“He chose us in [our Lord Jesus Christ] before the creation of the world to be holy and blameless in his sight.” (Eph 1:4).

And :

“By [the Son] all things were created: things in heaven and on earth, visible and invisible, whether thrones or powers or rulers or authorities; all things were created by him and for him.” (Col 1:16)

And:

“This grace was given us in Christ Jesus before the beginning of time, but it has now been revealed through the appearing of our Saviour, Christ Jesus..” (2 Tim 1:9).

And Jesus says:

“Come, you who are blessed by my Father; take your inheritance, the kingdom prepared for you since the creation of the world.” (Matt 25:34).

To agree that God is the centre is a big step. If he’s that capable of governing his world, you might also wish to consider if he would not also govern how he reveals himself in Scripture. But you still engage in a highly arbitrary process of taking some biblical stories (which many reject as bronze-age fiction) as true in detail, whilst sitting in judgement on the biblical writers far closer to the texts than we are.

It’s simply not true to say we know much more through modern knowledge: we know different things, and some on which we are far more ignorant than any of the Bible writers include their sources, their relationship with God as inspirer, their culture, their language, their worldview. We don’t even want to understand them, because we’re so sure of the superiority of our own way of seeing the world.

Remember that archeology depends on sifting through what little remains of the rubbish of dead people: they actually lived in their world. Most kings, and even many nations, together with most of their ideas, have been entirely lost to history. At best, our discoveries help us to begin to reconstruct what they knew and understand it more clearly: to pretend to understand their texts better than they did – and even more, to claim to know the plans of God better than they did – is, shall we say, a little self-confident.

This from you is truth worthy of approbation: “It’s not about conflicting with God’s will but rather learning to operate according to God’s will through our own volition. He doesn’t force it on us. He made it our choice.”

But the way you phrase it shows that you haven’t yet grasped that, to the Bible writers, the question of God’s needing to “force” the choices of wills he created and governs is pretty meaningless. That is one of the items of knowledge that modern popular conceptions of free will have completely lost, and need to work hard to recapture.

Okay, take Babel….

6 The Lord said, “If as one people speaking the same language they have begun to do this, then nothing they plan to do will be impossible for them. 7 Come, let us go down and confuse their language so they will not understand each other.”

God’s decision to scatter them was based on his observation of what they were doing. He’s reacting/responding. Which, by the way, what he observed in these humans accurately describes what humans were doing in Sumer in that early phase.

Now that doesn’t mean God had no idea. Like what he told A/E after the fall. He could explain to them what would happen. He could anticipate, predict, but not know. And, to be clear, this doesn’t in any way diminish God’s power or authority. I think it just underlines the significance of free will. What a gift it truly is.

It is true there’s quite a lot the authors knew that we don’t, especially in regards to contemporary knowledge and cultural aspects. But there’s a lot we as readers know that other readers all throughout history did not know. Context not available to those who long ago determined what’s what in the bible and just stuck with that view. Like Adam being the first human, for example.

We can place a lot of this in context historically. We can use knowledge gained to reconstruct the environment and political climate of the time these stories are set in. Flesh it out to better understand.

But you’re right about my statement that Jesus was a reaction. Statements like “By [The Son] all things were created …” are stated often. My mind in this goes to the whole first/second Adam concept. Jesus did what A/E and every human since failed to do.

What was accomplished through Jesus was always the intention. I think it just took some doing to get there. Because of free will, God could not just speak it into existence and it become all on it’s own what’s intended. Because of this volatile element at play it took more of a hand’s on approach.

That God works his purposes slowly and mysteriously taking into account the evil acts of men and angels is not in dispute… at least, once we take the authority of the Bible seriously. And to accept as factual what is said of God’s words and actions over Babel requires such an acceptance.

But is that to say any more than that God is a God of relationship, who deals with his creatures individually according to their natures? The Bible presents that as the case even with the natural world, in which God (contra the materialist naturalists) is completely hands on in his government.

So, with the creation of rational man, with free will, he deals appropriately (but as Creator, not simply as a rival will). What interests me more is God’s aims and intentions in creating mankind that way, and in interacting with them in that way. That’s the overarching theme of my book, The Generations of Heaven and Earth.

We don’t have a God who suddenly sees that humans now have free will and are causing problems, but a Triune God who, from before creation, desires to see it justly populated and ruled by rational beings in his image in harmony with him, and knows that will be achieved only through his Son, demonstrating God’s love through his suffering, and so bringing greater glory to him.

What is wonderful about the “big picture” presented in the Bible is that it shows, like a classical folk tale, how an apparently insurmountable block to God’s plan is overcome by love and truth, so that not only is evil and injustice righted, but every part of the original plan comes to fruition in a way that brings him greater glory than if there had been no opposition.

Another way to look at this is that opposition (and I agree free will is a prerequisite, but not a determinant, of that) is what creates story, or drama. Contrast Genesis 1:1-2:4 (which I take as an introductory prologue to Genesis, the Torah, the Tanach, and the Christian Bible all) with Gen 2-3. The creation is not (as many scholars have pointed out) a story at all: God speaks, and it becomes. The “story” proper only begins when Satan questions and Adam and Eve disobey, and the proper focus for our attention is then “How is Yahweh going to get out of this one?”

The “Big Thing” then is that God decided to make creation a “story” at all, to put such drama at the heart of human existence. We all live by stories, it turns out, and that is congruent with the way God has formed things.

So whilst free will is a sine qua non (and is simply presumed by the writer of Genesis, being part of universal human experience), it is not the point of the story. Or from another angle, we don’t understand God’s actions any better by tracking the evolution or creation of free will, but by asking the text what God’s intentions were for the world, and how he achieved them against angelic and human opposition.

And that points us, increasingly, to Christ rather than ourselves.

Re: creation as a “story”

Yes, exactly. The whole thing is a presentation, presented in a way that we’re good with. Wisdom cannot just be given. It has to be earned. Learned. Experienced. Creation with us isn’t just forming us from some dust and breathing life into us. There’s more to it than that. We have to be molded.

And a capability like free will is a huge responsibility and requires wisdom. Without free will you don’t truly have a relationship. You can’t really have a relationship with yourself.

Re: Understanding God’s actions by asking the text what God’s intentions were

I agree. Doing that is what led me to believe God’s intentions were breeding. Observing favorable traits, breeding from that stock, isolating the herd, etc.

But as far as tracking the evolution or creration of free will, the story being told here is the definition of epic. The events of these stories are said to have altered the world. So, we should be able to see that. And I think we can. And seeing it explains a lot about humanity and how we came to be where we are now.

Increased agreement here. But:

I really can’t see how you get selective breeding from a text that pre-dates the concept of breeding for inherited traits by many millennia. Breeding of this kind only really took off in the eighteenth century, and so it was as “cutting edge” science that Darwin used it to bolster his theory of natural selection.

Before that, individual variations were assumed to be unstable, and “genealogy” (as a useful paper on the development of the concept of race states) was a term “rather associated with the vocabulary of nobility and breeding.”

That the writer of Genesis had no concept of genetics even at this basic level of “selection for the desirable” is shown by the example of Jacob in Gen 30, who outwits Laban by selectively breeding the striped and spotted beasts Laban allows him: and he does so by placing spotted sticks before them as they copulate, not by breeding from the desired characters.

It’s not clear from the text whether this reflects common ancient practice, or a supernatural dependence on God, but certainly even in mediaeval times it was believed that if a woman imagined she was in the arms of another man than her husband, her baby would resemble the other man: which is just one form in the belief in the inheritance of acquired characteristics that really only disappeared after Darwin, 1859.

So if we conclude that even though no ancient author would have know it, God was actually practising nineteenth century “improvement of the breed,” what traits do you think he was selecting for, given that no complex behaviours have been shown to be genetically determined?

I look at the three examples; Noah, Abraham, and Jesus

When Noah was selected, it says the Lord saw how wicked humans had become, but Noah found favor in the eyes of the Lord.

With Abraham, He tested to see if the desire of Abraham’s will would outweigh God’s will.

And with Jesus we’ve got the first/only human to have no wickedness/sin and who’s will never conflicted with God’s.

Interesting list, which suggests to me you must be using “selective breeding” rather metaphorically than literally. God selects these three, it is true, but I question whether “good breeding stock” is at all relevant. In detail:

NOAH: Noah finds favour with God, but we are not told why. It’s tempting to assume it is because he alone is righteous, given that in 6:5 God sees that “every inclination of the thoughts of [man’s] heart was only evil all the time.”

But what’s this? The flood happens, and only Noah, his three sons, and their wives remain (in the terms of the story). God’s anger is assuaged, peace is restored, and God promises such destruction will not happen again… “even though every inclination of man’s heart is evil from childhood.” This must apply to Noah and his sons, so Noah, then, is still as corrupted as the rest of them – his favour with God must then be through divine grace, not human worthiness. He proves it by his subsequent shameful drunkenness, which nevertheless does not abrogate God’s promise.

Hebrews 11 says that this grace worked through Noah’s faith. But faith is not a hereditary trait, or at least if it is my unbelieving family members all missed the gene, as of course did the majority of Noah’s descendants. As Joshua Swamidass points out, genetic inheritance is very unreliable and unpredictable.

ABRAHAM: God’s promise to him comes at his first call, not after he has proven his worth. Indeed, in Romans 4 Paul stresses how he was accepted as righteous simply through his faith in the promise (Gen 15:6), before he “did” anything. Paul speaks of circumcision, in the Romans context, but his acceptance also precedes the episode with Isaac and the sacrifice.

In fact, this faith is in the promise of the future “impossible” son and heir through whom all the blessings will come (whose qualities, at that point, do not even exist to be tried), and in the same chapter God converts the promise to a divine oath, and confirms it as a binding covenant in ch 17 – all before Isaac is even born, let alone offered in sacrifice.

It seems to me that the Bible does not even interpret the sacrifice episode in terms of a test of will, but in terms of a test of faith. Heb 11 (again) expresses this as Abraham’s trust that God would be able to raise Isaac from the dead if necessary, and that is actually suggested in the Genesis text by Abraham’s assurance to his servants that they would both be back once the sacrifice had been completed.

A key to understanding this is to realise that “test” (Heb bachan), like its Greek equivalent, carries the nuance of refining as well as testing, as in the business of purifying metals. You can see this in texts like Job 23:10:

“When he has tested me, I shall come forth as gold.”

Or Prov 17:3:

The crucible for silver and the furnace for gold,

but the Lord tests the hearts.

Or Jer 9:7

“See, I will refine [=melt] them and test them,

for what else can I do because of the sin of my people?”

Or Zech 13:9:

“This third I will bring into the fire;

I will refine them like silver

And test them like gold.”

So nearly always in Scripture, “testing” carries the dual idea that it reveals the state of the heart, but ALSO purifies the heart by floating off the dross. And the revealing is often to the one tested, not to God: so Ps 139 has expounded at length how God already knows all there is to know about David, but it ends with a plea for God to test him an “know” him – to reveal and refine to David what is offensive and needs to change.

If we consider the ongoing genealogy of Abraham, the covenant-line proceeds from Isaac through the younger twin Jacob, and in Rom 9 Paul points out that this is entirely by grace, for the twins had at that point done nothing, either good or bad, to merit the choice. Indeed, earlier in Romans Paul says that the true descendants of Abraham are not his genetic offspring, but those who share his faith, even if they are Gentiles.

JESUS: Jesus not only had no genetic descendants, nor the usual human parentage, but was sinless because he was the incarnate Son of God, born of a virgin. “Before Abraham was, I AM.” In fact, one of the perennial theological questions down the centuries has been how Jesus was not corrupted by the sin of his mother, leading the Catholics to the conclusion of Mary’s sinlessness through an “Immaculate Conception” (Or “Immaculate Contraption” as one school-child put it!). Not a great solution, in my book.

I don’t personally subscribe to Mary birthing Jesus as a virgin. It never actually says that. And it seems to me what Jesus accomplished is made all the more significant if He too is human.

The issue with Noah’s being drunk was what Canaan did. I’m not sure I can agree that being drunk confirms evil in Noah’s heart. That makes it sound more like God favored Noah at first, but that one night he got drunk and that changed things.

I’m not entirely sure the breeding practices were genetically driven. I suspect it more had to do with realizing the holy spirit through Jesus. This is why it’s helpful to discuss this with you. You’re much more versed in this aspect of it than I am.

The trail I’m picking up on looks something like this. God breathes the ‘breath of life’ into Adam. Later, in Gen6 God says His spirit will not contend with humans forever. Then, for example in Ezra, when they’re taking issue with breeding outside of the tribes, they speak of the ‘holy seed’.

Keeping this ‘spirit’ in a small/controlled sampling of humanity, and not letting it spread and dilute, as it will not contend forever … Then dot, dot, dot. That’s where it just kind of stops.

All of this I imagine plays a role in writing God’s laws on the hearts of men. Does any of that track in your view? The physical evidential trail just kind of dries up at this point. It starts getting way too speculative.

Well it does, actually – Matt 1:23, Luke 1:34. Denying the virgin bith lays you open to an astonishing number of historical heresies, the bottom line of which is that the Council of Chalcedon showed how Jesus is truly human, but also fully divine.

Well, if we accept your premise that God doesn’t know human will until it acts, that’s entirely possible. But the fallacy is that God chose Noah on the basis of his righteousness at all: grace does not operate on the basis of works.

The Holy Spirit acts in various ways through Scripture (as befits a Person of the Trinity). In Genesis you have to factor in that there is no absolute distinction between “breath” and “spirit”: it is the same Spirit who gives life to mankind, but also to every living thing – see Ps 104:30; Gen 7:22.

What marks the chosen “line” of God is not primarily the Spirit in them, but the Covenant *with* them. Ezra’s “holy seed” is about the inheritance of the Covenant made with Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, ratified in a more limited way by the Covenant on Mount Sinai.

To put the work of the Spirt in Israel briefly, the Spirit is said to be among them (Isa 63:11), working in the prophets, the kinds and anointed priests. Indeed, it is the specific promise of the New Covenant that he will put his Spirit in the hearts of all Israel (understand an expanded Israel here, in New Testament terms), eg Ezek 36:27; Joel 2:28-32, quoted in relation to the giving of the Spirit at Pentecost by Peter in Acts 2:17-21.

So think in terms of grace, Covenant and gift, rather than in terms of human endowment, and you’re getting c;loser to the biblical viewpoint. It’s revealed, spiritual truth – and so the physical evidential trail was always going to bit a bit of a wild goose chase.

Re: Spirit/Breath in Genesis

I think there’s an important distinction between creation of life in Gen1 and the creation of Adam in Gen2. The universe/Earth/life all appears to have just formed all by itself because that’s what it was told to do. But with Adam, he was created apart from all of that. Made by the same elements, but formed specifically and breathed to life apart from the tree of life we all branch off of.

And Gen6 appears to underline this distinction when it speaks of two different groups, the sons of God and the daughters of humans. Humans, who it describes as ‘mortal’ in comparison, only living 120 years. It is this intermingling that God is referring to when He says His ‘spirit will not contend with humans forever’. I think this is important.

Re: Virgin birth

First, I mistrust church councils. This is why I’m so much more comfortable in those early books. The later it gets, the more humans get involved, the more influence of human-based agendas gets mixed in. If I read the NT books in the order in which they were written, they tend to bend more magical the later they get. And when you include with that possible confusion in translation between ‘virgin’/’young’, it all gets a little iffy.

And I don’t mean to speak out of line or be in any way disrespectful. I don’t see this as diminishing Jesus in any way. In my eyes it makes it all the more significant if he’s not half human/half God, but all human from the stock that God carefully molded over a hundred generations. It completes the story of the OT. As Jesus said, He fulfilled the law.

Re: “if we accept your premise that God doesn’t know human will until it acts”

To clarify, it’s not ‘until’. Time is irrelevant. It’s only whether or not it happens. In the case of Noah, if at anytime in his life he got drunk, God knows it. Sees it. But in the case of Abraham, if the test had never been done, then there’d never be an event throughout the course of Abraham’s history to look to to see what he would do. The test had to happen for the decision to happen to be known.

Re: So think in terms of grace, Covenant and gift, rather than in terms of human endowment

What makes it a Covenant, rather than a promise, is because there are requirements for the other party. A promise God carries out Himself. A covenant God carries out with cooperation.

And all of this is in service of the same intended result. Human endowement is not something the authors would be speaking in terms in. It’s the observable result.

Indeed a covenant is a two-way street. Note, though, the way that the key “new creation” covenants are “grace intiatives” on the part of God, which is why the theologians distinguish covenants of works and covenants of grace. As Augustine says, God gives what he demands.

For example, that mysterious event in Gen 15 is a supernatural version of the ancient covenant ceremony in which the parties solemnize the agreement by passing between the pieces of a sacrifice. In this case, though, Abram is put into a deep (visionary) sleep, and God alone, in the form of a burning torch, passes between the pieces. No conditions are set in that chapter – and in ch17, when circumcision is introduced as a covenant sign, obedience follows the promises. So it’s not “If you do A, I will do B,” but “Because I will do B, you must do A.”

The other prime example is the New Covenant in the future Christ introduced by all three major prophets at the very point of the failure of the Mosaic covenant (which was clearly one of works) in the destruction of the temple in Jerusalem. In these texts it’s all about God putting a new heart and Spirit within them, which will cause them to choose his will and keep his law: Ezekiel even has the nuance of saying, in effect, that it’s not for the people’s sake he’s doing this, because they are demonstrably incompetent and rebellious, but for his own glory.

It’s that power of the covenant to produce what it demands that makes Christianity a unique religion, and why (of course) it’s delivered specifically to sinners and outcasts.

But the fact that human endowment (in terms of forgiveness, godliness, righteousness, the indwelling of the Holy Spirit, eternal life and participating in the glory of God) are all observable results I won’t dispute:

I add in passing that the complete consummation of these promises awaits the return of Christ, which is why the gift of the Spirit is referred to as a “deposit” or “guarantee” of what is to come. But that doesn’t alter the core truth.

Re: point of the failure of the Mosaic covenant

Was it a failure? Or was its purpose realized (Jesus), making a new covenant necessary?

Deep waters! There’s a need to distinguish the “deep counsels of God,” eg the salvation plan in Christ purposed before the creation of the world, and the genuinely evil effects of sin against the stated desires of God.

So for Adam (freely) to disobey God is an evil disruption of the stated purposes of God for him, though it may have been anticipated and even serve to increase the ultimate good. Remember those warnings in 1 Corinthians, where people object that since God brings greater good out of evil, why not do evil that good may come – Paul shoots them down in flames.

So we can, with hindsight, keep in mind that God always intended to work his purpose in and through Christ, though the Bible speaks of it as a secret hidden within the Godhead itself until the right time.

Israel’s failure began at Mount Sinai, when they lacked faith, and feared and declined to meet God face to face and delegated Moses instead. So they ended up with a law-based covenant, which they were unable to keep – thus paradoxically stressing their separation from God instead of their calling. That explains the New Testament “critique” of the Old Covenant as unable to save, yet not because God’s law was deficient, but because human sin weakened it.

That critique, though, suggests (as I think you suggest) that the very failures of Israel prepared the way for the gospel; firstly in the whole historical process that led to Jesus and his circumstances, and secondly in showing the need for a better covenant (Heb 8 7-12).

Maybe one way to interrogate this is, “Why this story of the world, rather than some other, maybe less troubled one? In the end, God is the Creator, for good reasons, of the story he wishes to tell. We, however, are characters in the story, and need to act as such rather than second-guessing the author.

The whole garden scenario is set up that way it seems. Adam/Eve are dropped into an environment where only one rule exists. This one tree is off limits. I don’t think the serpent turning up and encouraging them to question and plant doubt was a mistake. It, like with Abraham, was a test of will. Their individual will/wants pitted directly against God’s. Which would overrule the other?

Yes, I think Adam/Eve’s actions were definitely anticipated. Probably part of the ultimate plan. A necessary beat in the overall story.

And the same goes, I feel, with the failure of the first covenant. Another necessary beat in the story. It helps explain why everything was done the way it was and why it was all necessary.

And it all, in my view, is in an effort to realize free will. To make it possible for beings with free will to coexist with God.

Re: In the end, God is the Creator, for good reasons, of the story he wishes to tell. We, however, are characters in the story, and need to act as such rather than second-guessing the author.

I think we’re more than characters. We’re co-writers. He gave us a pen. That’s where it gets tricky. And I don’t want to give the impression that I’m second-guessing the author or that I think in any way this diminishes God or his power.

I think it’s exactly that. A story. A presentation, really. It illustrates all we need to know and understand. If you do this, this happens, this, this happens. God literally tried everything. This is not His failing. This is him illustrating. Showing us.

We get to see first hand through human history playing out that not one of us has all the answers. Not one of us is worthy. We’ve all been given the chance. There’s really no argument how this needs to work and who’s in charge.

I broadly agree with these conclusions: the main distinction I want to maintain about “necessity” is that for God to will something in his ultimate, hidden purposes is significantly different from his making it inevitable within creation. It’s the difference between created law and his sovereign choice.

And so it is very different to say that it is in the nature of free wills to rebel (Jesus belies it), and that God foresaw, allowed for, and even in some sense purposed the fall of mankind, for a greater purpose. In just this way, the Resurrection had to happen for the world to be saved, but it was not in the nature of a human being to rise after three days.

On the nuanced understanding of God as character in the book, or man as author, the best reply I can give is apiece I wrote 4 years ago here.

Re: “And so it is very different to say that it is in the nature of free wills to rebel”

I don’t think it is. This is why the serpent’s role in the garden was significant. It required a push. Otherwise I venture to say it wouldn’t have happened.

And it’s not to say that it’s in the nature of free will to rebel. It’s like taking a train off of its tracks. Its nature is to locomote. It’s the track that guides. Without a guide the train just pushes forward. Acts. With no guidance. Not rebelling. Just acting.

It is not in our nature, at least not yet, to behave within the bounds of God’s will. That’s the goal. But it takes some doing.

As for the piece you wrote, that’s really good. And goes right to the heart of many of the things I’ve been speaking about. Like guidance in the natural world. Yes, it’s all in God’s control, but it’s not something that requires His constant attention. He set the laws in place. And when matter/energy is introduced into the environment these laws create, nature happens.

Like life. God imbued it with purpose, commanding it to be fruitful and multiply and fill the earth/seas. And that’s what life does. Survives. Thrives. Multiplies. Adaptation is part of that. God didn’t have to design specific characteristics for each animal in each environment. He imbued life with the tools and it simply continues on according to God’s will.

For Jesus to have been the intention since before creation, the fall was something that was inevitably going to happen.

I’m jumping in here very late to the party, but last year I was independently researching the same thing, through the intellectual pathways opened up to me by René Girard’s Fundamental Anthropology (mimetic theory, the scapegoat mechanism, Revelation by Christ of this “satanic” mechanism” etc.) and Aquinas’ variety of Aristotle’s theory of hylermorphism, Kierkegaard’s work on Original Sin, and some other works, including Kenneth Kemp’s paper on monogenesis and “theological man”. When I turned back to investigate the Bible, I started asking questions about Genesis and science, about the meaning of the Fall, etc., and came to some very parsimonious and profound conclusions that, to my astonishment, agree perfectly with yours and S. Joshua Swamidass’, that were completely unknown to me (originally merely an Australian lawyer and political philosophy teacher stuck in France!).

I have been compiling a sprawling manuscript on the subject, but acknowledge taking many of the theological, metaphysical, epistemological tangents that tantalisingly open up once one attempts to answer the question, “what is man”. It is with great enthusiasm then that I’ve discovered yours and Joshua’s work, which has helped me enormously in buttressing my hypotheses with scientific support.

Before I enter into conversation with you (or Jeremy, who here has asked some very important questions), I was wondering if you were familiar with any of my abovementioned influences, particularly Girard, in undertaking your own research?

Hi Levi, and welcome to the Hump.

I don’t know how much you’ve dug into Joshua’s/my “Genealogical Adam and Eve,” but you’ll be pleased to know it was actually conceived by a lawyer, David Opderbeck around 2010. He first made the link between the “genealogical ancestry” work of Rohde et al, and applied it to the biblical Adam.

To answer your question, I haven’t read Girard, I’m afraid, was very influenced by hylemorphism (firstly via Ed Feser), have only touched on Kirkegard’s work through a BioLogos/Hump contact, and am familiar with Kemp’s model through BioLogos and Joshua’s site.

Use of different sources shouldn’t surprise us, I guess, as the whole approach is an eclectic one spanning theology, anthropology, biology and everything else. That probably gives each of us who are interested a different part of the jigsaw, assuming of course that the basic approach is valid. If it is, you’d expect all those fields to fit together somehow.

I probably ought to read Girard. Perhaps you could summarise what you’ve gained from him and make recommendations: glancing at his biography the very fact that he’s not in the same boat as Foucault and Derrida attracts me to him!

Thanks for your quick response, Jon. I’m also a great admirer of Ed Feser’s work, which I came to via Alasdair Macntyre. Like both of these, I was a typical liberal atheist steeped in a background rationalist, positivist and utilitarian/Marxist culture, but the a nagging commitment to the truth led me to discover, as you described in the post, the shocking surprise of just *how true* the Bible really was.

I was born into a secular Jewish family, and so had a familiarity with the Bible stories from a very different value system. It was the discovery of René Girard’s work, while I was lecturing in Paris in the year of his death, that my whole world was upended. Until then, I had been a defender of natural law for a few years, under the influence of the invaluable Schopenhauer, partly as a resistance to Nietzsche, whose works nevertheless had a profound impact on me; it was as yet inconceivable to me that the proper grounds of the natural law lay elsewhere, although I had some inkling that Schopenhauer had peremptorily cast out the question of “Being” as “speculative theology, which is not a subject for rational philosophical inquiry”.

As my whole philosophy depended on a notion of the Good, I was trying to find grounds for understanding the problem of evil that were not merely allegorical or mythical, and which did not lead to a manicheism or to an essentialising of evil. But this was all very intellectual. Once I read Girard’s anthropological masterpiece “Violence and the Sacred,” then “the Scapegoat”, I had a radically knew approach to the problem, as a *human* problem, something to do with our violent origins, which become the origin of the symbolic as the basis for the intellectual faculties of language, and of reason itself. It wouldn’t do justice to Girard to give too summary a treatment of his oeuvre, but fortunately he himself offers three parsimonious hypotheses that together form his Mimetic Theory, namely, that

1) man is motivated by uniquely strong metaphysical desire or mimetic desire, acquisitive desire mediated by a model or idol, and although the object may be sought, the true nature of desire is “to acquire the being of the Other,”; and

2) that in the inevitable conflicts of acquisitive mimesis, escalations of rivalry go unchecked by natural moderators of rank (size, horns, hairy mane, testosterone, strength etc) leading early hominins to crises of undifferentiated chaos and tribal self-destruction which, at some point in archaic history came upon and began to practice a remedy: the victimary or scapegoat mechanism, the transferal of all-against-all to all-against-one. The accusation of guilt by all against one is in an important sense both arbitrary and fundamental, because his violent expulsion produces unanimity and cathartic peace, and can thus, according to Girard, be supposed as origin of the ambivalent gods of archaic religion, and of taboo, prohibition, ritual and myth; and

3) finally, that the Scriptures are, amongst other things divine, the *revelation* of this mechanism at the foundation of the world as the “satanic” (“How can Satan cast out Satan?”), and that God, through the resurrecting of certain victims (the blood of Abel cries out; Isaac; Joseph; Job; Jonah etc.), is breaking into the closed symbolic space of the sacred to reveal both that man is the origin of these violent gods and, by rescuing man from sin, that the true God is merciful and loving, culminating in the story of Christ’s crucifixion and resurrection. After Christ, the archaic sacrificial system is broken forever by Christian witness, expressed profoundly by the Greek word for Holy Spirit, “Paraclete” from parakleitos or “advocate for the defense.” We now know *we have scapegoats* and can no longer form unanimous accusations nor therefore generate myths. Girard thinks that it is because we no longer burn witches that can exercise reason and science, not the other way around, and practice victim-centred justice rather than Caïaphan ends-justifies-the-means scapegoat politics etc.

Finally, in his last work, “Battling to the End”, Girard proposes an apocalyptic conclusion to our age and this world, in which Christianity’s message of love and positive reciprocity has destabilised, but has not conquered it sufficiently, because Satan, although seen “falling like lightning from heaven” by the revelatory effects of the Cricifixion and Resurrection, nonetheless remains prince and principle of man’s fallen world, being the archaic mechanism of accusation and expulsion which love has not overcome, yet from which no pagan order or peace can be founded as of old.

Girard presents a naturalistic account of man’s violent entry into his symbolic and religious nature, but allows for sufficient ambiguity for the role and work of a transcendent God. His mimetic and sacrificial approach to interpretation takes on ancient myths, and Freud, and Nietzsche, and knocks them out of the park with extraordinary scholarship and humble, surgical prose.

Reading the rest of René Girard’s work forced me to totally reconsider everything I had nitherto believed, and I subsequently withdraw from my legal career into deeper study, which has led me back to Aristotle/Aquinas, and to a firm faith that Jesus is truly the one the Jews were waiting for (no small avowal for a modern Jew to make!). Now, being a critical person, and as I had been understaking a work criticising my beloved Schopenahuer, I realised that Girard helped understand Schopnehauer’s brilliant errors, in such a way as to allow for a theory of Reason that collapses into the following dichotomy: The Logos of Heraclitus vs the Logos of John, or, in other words, the spiritual disposition or “wisdom of the heart” determines whether one will see the dialectic, or striving of opposites, as the essence in all things, or, conversely the unity and divine order behind apparently divided things.

But in the same critical spirit, I saw that Girard’s anthropology was unsatisfactory on a few important questions, notably the doctrine of original sin, and ultimately, on the problem of evil, which one would be forgiven for recognising in Girard’s work as falling down for the Nietzschean claim against Schopenhauer and Christianity, that if man’s origin and essence is violent striving, why at all should he deny himself his nature, rather than affirm it?

I solved this problem, I believed, with some grace from God, who showed me that the “man” Girard was brilliantly revealing, was not “man” at all as we ought to understand ourselves, but the man-material into which the loving image of God was breathed, creating Adam, the first true man. This archaic and proto-pagan man may be the model, however, (or even the very *nachash*, a diviner who was, after all, capable of walking and talking, and capable of modeling behaviour for Adam) that Adam fell into imitating, in disobedience of his unique inner divine command. I came to this theory by drawing upon hylermorphic causality, where form in an important sense “precedes” its matter, and where, notably, the soul or form of man is an intellectual, rather than strictly physical type, and would therefore make man physicially indistinguishable from the men from whom Adam was made. This also has tremendous consequences for the broader theory of natural evolution.

I won’t burden you with all the details as they’ve come to me, because the idea fructifies with an almost exponential fecundity of possibilities, and because I’m afraid I’ve failed to give them a fair description or good defense so far, in this format. Instead, I look forward to maintaining a dialogue with you, and to following more closely yours and Joshua’s works

Sorry, I should have specified that by the “same thing”, I was referring to a genealogical approach to Adam and Eve that is consistent with a scientific theory of monogenesis as well as evolution of the material world.

Understood!