Sy Garte’s comment on the last post, mentioning panspermia, and GD’s subsequent admission of a liking for science fiction, renewed an intention I formed a while ago to draw together thoughts on the relationship of possible extraterrestrial life to theology. Overall there seems to be a mainstream skeptical generalisation that the existence of ETs would be a threat to Christianity, which echoes a perception that Fundamentalists “don’t hold with Space” (as some Luddite told my father shortly before Sputnik 1 showed that Space didn’t hold with him).

Declaring interests first, I have to say that I drank in science fiction almost with my formula feed thanks to my father’s reading, loved astronomy as a kid and (to my shame) spent my early teens with an avid interest in UFOlogy. The last waned as I acquired the critical faculty and a real faith, and the first when I acquired a wife who’d done English at college and contributed some classical literature to our shelf.

Declaring interests first, I have to say that I drank in science fiction almost with my formula feed thanks to my father’s reading, loved astronomy as a kid and (to my shame) spent my early teens with an avid interest in UFOlogy. The last waned as I acquired the critical faculty and a real faith, and the first when I acquired a wife who’d done English at college and contributed some classical literature to our shelf.

I think the “ET life sinks Christianity” idea is something to do with thinking that Christianity makes earth’s story unique and central, whereas a populous universe makes life natural and inevitable, disproving God as Darwinism (supposedly) does. As for “Fundamentalist” skepticism, some of it undoubtedly does arise from a literalist assumption that if the Bible divides reality into heaven and earth, and only teaches about organic life on earth, then that’s all there is.

But in the blogosphere, at least, some of the Christian skepticism arises from the same kind of reaction to arrogant metaphysical assumptions of the scientistic kind that one sees regarding evolution. Statements along the lines that “the universe must be teeming with life, so we can assume Christianity is wrong” are rather asking for deconstruction.

And such deconstruction is, up to now, pretty easy and, even to me, inviting. Decades ago, I saw that the widespread use of Drake’s equation to show the inevitability of life was fraudulent when the values of all seven variables were mere guesses reliant on a dataset consisting of one planet with intelligent life – I stopped believing in a perfect straight line based on one point and the origin in O-level physics.

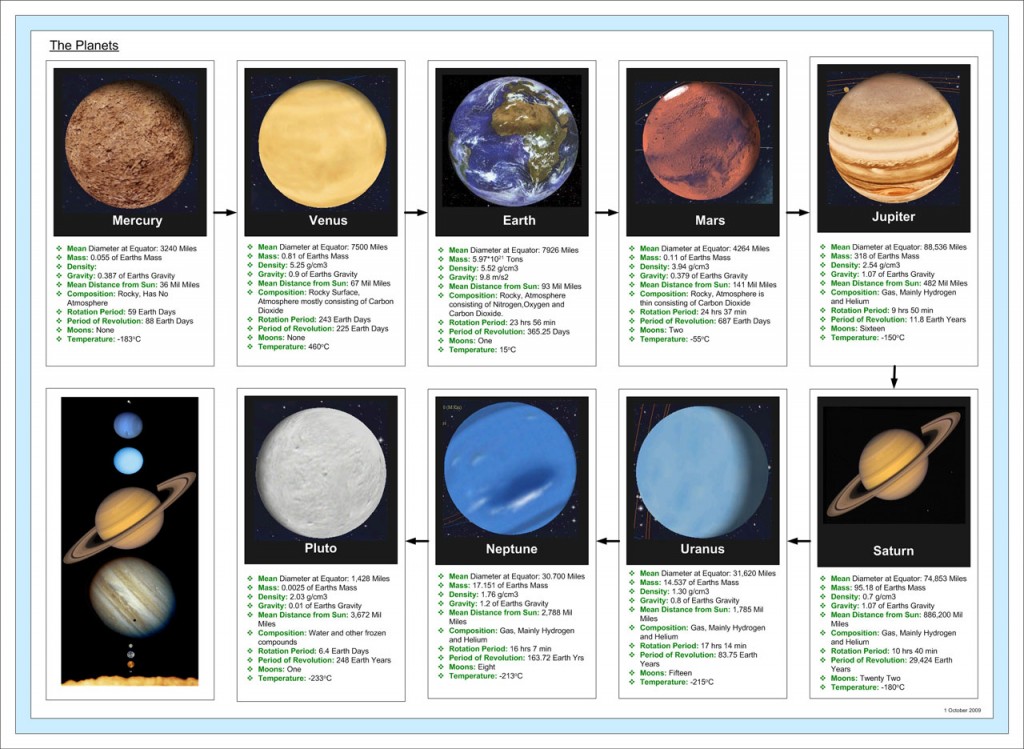

Ward and Brownlee’s equivalent formula in their Rare Earth book, which substituted necessary factors for advanced life thought likely, on somewhat better evidence, to be unique to earth, puts the thing into relief – one can use equally valid equations to produce answers between “billions” and “zero” for the number of other civilisations.

Ward and Brownlee’s equivalent formula in their Rare Earth book, which substituted necessary factors for advanced life thought likely, on somewhat better evidence, to be unique to earth, puts the thing into relief – one can use equally valid equations to produce answers between “billions” and “zero” for the number of other civilisations.

There’s much more to be said about the reasons for the hype surrounding the regular NASA press releases that “X may indicate the possibility of the likelihood of the presence of building blocks of life”. Is the evident angst theological (maybe we’re not special and accountable), or existential (maybe we’re not all alone), or just financial (maybe we’ll keep our funding stream if the mirage of ET life continues to beckon)? But here I want instead to look at the pros and cons of alien life theologically.

Before Copernicus, the question scarcely arose. The standard geocentric Ptolemaic model, with Aristotelian roots, consisted of spheres of increasingly celestial (and usually living) entities culminating in the infinite realm of God’s heaven beyond the stars. The planets and stars might influence us, but not vice versa, and it would be irrational to suppose these higher realms to be inhabited by lowly creatures like us.

It was the post-Copernican insight (only demonstrated empirically a couple of centuries later) that the stars were actually suns like ours at huge distances and possibly surrounded likewise by planets, that raised the issue of “life on other worlds”. As I wrote here the first response was for educated Christians to assume all worlds must be inhabited rather than barren, in keeping with God’s goodness. It would even help support the dominant philosophical “principle of plenitude”, by which God must have created every possible living form: a near-infinity of other worlds made space for those not found here on earth. And since the biggest gulf was between mankind and God himself, most worlds could be assumed to contain more glorious creatures than us.

It was the post-Copernican insight (only demonstrated empirically a couple of centuries later) that the stars were actually suns like ours at huge distances and possibly surrounded likewise by planets, that raised the issue of “life on other worlds”. As I wrote here the first response was for educated Christians to assume all worlds must be inhabited rather than barren, in keeping with God’s goodness. It would even help support the dominant philosophical “principle of plenitude”, by which God must have created every possible living form: a near-infinity of other worlds made space for those not found here on earth. And since the biggest gulf was between mankind and God himself, most worlds could be assumed to contain more glorious creatures than us.

Penman once sent me a quote from the Puritan Richard Baxter which demonstrates how conformable to mainstream Protestant doctrine this new thinking soon became:

I know it is a thing uncertain and unrevealed to us, whether all these globes be inhabited or not. But he that considereth, that there is scarce any uninhabitable place on earth, or in the water, or air; but men, or beasts, or birds, or fishes, or flies, or worms, and moles, do take up almost all; will think it a probability so near a certainty as not to be much doubted of, that the vaster and more glorious parts of the creation are not uninhabited; but that they have inhabitants answerable to their magnitude and glory.

What theological problems does this pose, which might lead Christians towards denying the probability of ET life?

I’ve mentioned biblical literalism: Genesis says life was created on earth (and the Bible mentions only angelic beings in heaven). But the fact that the Bible is addressed exclusively to the history and future of our own realm does not exclude other, similar, worlds per se – it just ignores them as irrelevant to our story. Histories of the world, similarly, omit the history of Mars or Sirius B. The Bible, quite reasonabvly, doesn’t even mention China or Australia for the same reason.

I’ve mentioned biblical literalism: Genesis says life was created on earth (and the Bible mentions only angelic beings in heaven). But the fact that the Bible is addressed exclusively to the history and future of our own realm does not exclude other, similar, worlds per se – it just ignores them as irrelevant to our story. Histories of the world, similarly, omit the history of Mars or Sirius B. The Bible, quite reasonabvly, doesn’t even mention China or Australia for the same reason.

The Bible’s cosmology is not, when understood properly, a problem. The creation, represented, as I’ve often mentioned, as a cosmic temple, sees the earth as the part of creation which is man’s domain, and heaven as the part of creation where God chooses to “presence” himself. I dealt with that here recently, on heaven as God’s non-dwelling, and it’s quite different teaching from the mediaeval cosmology in which the highest heaven appears to be God’s uncreated dwelling.

Instead, just as God chose to “presence” himself in the Jerusalem temple, though even its builder Solomon recognised that the universe cannot contain him, so at creation he condescended to be, almost symbolically, represented in the glory of the heavens. The Jews coined a word for this “virtual presence” – shekinah.

In later Jewish thought, God’s shekinah could similarly be present in Torah, and Christian theology places it supremely in the man Jesus Christ, but secondarily through the Holy Spirit in the Church and even individual believers (both therefore being described as God’s “temple”). As N T Wright points out, the hope of future “glory” for people, and perhaps the whole earth, at the parousia is nothing but the full indwelling of God’s shekinah, when God will be “all in all”.

This representative idea of “heaven” is no more incompatible with other, inhabited, worlds than the holiness of the Jerusalem temple is incompatible with spiders or swallows being there: it is heaven’s relationship to us that is the whole consideration in the Bible. In any case, “heaven” is not “outer space” in the sense of “everything out there.” To dwellers on some alien planet, the vastness beyond their own atmosphere could serve equally well as the representation of God’s boundless realm.

More problematic are those biblical passages in which mankind’s fall affects the whole cosmos, and his salvation likewise augurs a complete new creation. This is accentuated by the centrality of Christ and his ministry on earth to the whole redemption of the cosmos.

More problematic are those biblical passages in which mankind’s fall affects the whole cosmos, and his salvation likewise augurs a complete new creation. This is accentuated by the centrality of Christ and his ministry on earth to the whole redemption of the cosmos.

In part, the aforementioned biblical concept of heaven and earth as representing a “cosmic temple” still works with this. In whatever sense heaven is filled with God’s glory, that glory coming to fill the earth (as symbolised in the descent of the New Jerusalem in Revelation) is a new creation: our realm would be the new earth, the home of righteousness, and other races at some vast distance might still be irrelevant to us. We are God’s image on earth, created in the image and likeness of the Son – there is no reason why God could not create other “image-bearing” races to rule and subdue their own little domains.

On the other hand, the texts would equally allow that, were many or all worlds to contain their own equivalents of plant and animal life, redeemed mankind might be the sole example of a race made in God’s image, and our destiny – I think in the coming age rather than this – could then be to extend God’s Kingdom (and glory) to those other worlds. That appears to present a sufficiently challenging way to fill the time in the endless age to come.

My own sticking point – subject of course to the Lord’s unsticking it – is the common assumption that other worlds containing intelligent life would be subject to the same issues as our own – that is, issues of sin. Such a thing would, it appears, be a necessary conclusion to those holding to evolutionary theodicies, holding that quasi-autonomous evolution explains both “natural evil” and human sin as an inevitable by-product of the kind of creation God made, necessitating the Incarnation and Passion of the “cosmic Christ” to make a crooked universe straight. That either makes once more for a very geocentric theology – our history determines that of the whole universe – or presupposes that every intelligent race in the cosmos must fall into sin, and necessitate a separate “Christ-event.”

My own sticking point – subject of course to the Lord’s unsticking it – is the common assumption that other worlds containing intelligent life would be subject to the same issues as our own – that is, issues of sin. Such a thing would, it appears, be a necessary conclusion to those holding to evolutionary theodicies, holding that quasi-autonomous evolution explains both “natural evil” and human sin as an inevitable by-product of the kind of creation God made, necessitating the Incarnation and Passion of the “cosmic Christ” to make a crooked universe straight. That either makes once more for a very geocentric theology – our history determines that of the whole universe – or presupposes that every intelligent race in the cosmos must fall into sin, and necessitate a separate “Christ-event.”

More Fundamentalist believers can have the same problem. The singer Larry Norman was as much a pre-millennial rapture guy as any American charismatic, but disproved the atheist claim that all Evangelicals deny ET life when he wrote in UFO:

And if there’s life on other planets

Then I’m sure that He must know

And He’s been there once already

And has died to save their souls

However one gets to such a belief, it leads on reflection to a frighteningly utilitarian idea of the death of Christ – a billion races created entails a billion Edens depopulated and a billion crucifixions of the Only Son of God. Yet it is the unique love and grace of that act of God in becoming man in which Scripture glories : “Christ died once for all, to save sinners.”

Furthermore, the Bible teaches not that Jesus once spent time as a man, but that he became a man, intercedes as a man before the throne of God, and will return as a man to dwell with us forever. That all gets a bit diluted if he’s simultaneously incarnated as a billion other sentient species, dwelling face to face with them eternally on a billion other worlds.

To me, C S Lewis’s solution in the Perelandra trilogy is closer to orthodoxy (always bearing in mind that he created a fictional mythos for a metaphor of the gospel, not a serious theory of extraterrestrial life). In the trilogy, earth is “Thulcandra, the Silent Planet”, because alone of the worlds that God created, its ruler Adam took the unthinkable and aberrant step of rebelling against God’s commission. This necessitated the unique act (the talk of all worlds) of God’s Son, Maleldil the Young, taking flesh to redeem it. I think this accords with biblical teaching that sin is not an inevitable feature of creation, but an abhorrent blot upon it.

To me, C S Lewis’s solution in the Perelandra trilogy is closer to orthodoxy (always bearing in mind that he created a fictional mythos for a metaphor of the gospel, not a serious theory of extraterrestrial life). In the trilogy, earth is “Thulcandra, the Silent Planet”, because alone of the worlds that God created, its ruler Adam took the unthinkable and aberrant step of rebelling against God’s commission. This necessitated the unique act (the talk of all worlds) of God’s Son, Maleldil the Young, taking flesh to redeem it. I think this accords with biblical teaching that sin is not an inevitable feature of creation, but an abhorrent blot upon it.

If such were the case, there may be any number of wonderful races out there that need no redemption, whose image bearers in obedience to God guided their worlds into spiritual union with him. That would completely undermine the Copernican principle, because we would be uniquely privileged as the only world in which the Logos became his creation. But to our shame, that unique grace would only be the case because we were uniquely evil in making it necessary.

Perhaps that explains Fermi’s paradox – why would those races, this side of our full redemption, have anything to say to us?

I ‘like’ it. We are the pits of the universe. And salvation has to begin at the root of the problem: the worst case. So here.

Ian

It’s worryingly like those mass-killers in America, isn’t it? “The more people you shoot, the more you’re a celebrity.”

Just imagine all the other billions of civilisations, looking at maps of the Universe with an arrow showing up just where it was that that bizarre thing “sin” happened – and consequently, where the Lord showed the depth of his love.

I think it might also have been Lewis that remarked on God’s foresight in putting vast lightyears between everything as the necessary insulation against evil spreading itself.

Regarding your hesitation towards the apparent “privileged position” of thinking ourselves uniquely fallen vs. many races also having their own struggles with sin … Perhaps the same principles of plenitude that pervade our planet / system also pervade the universe so that we merely discover what nearly every other intelligent species is also discovering. Not so much that our unique history is determining that of the universe, but that the history of the universe is everywhere exemplified, including here.

And perhaps, just as we find that no human has an identical story for how he/she relates with God, maybe the same would prove true for intelligent species across the cosmos.

-Merv

Somebody said: “The vastness of the universe seems a bit of a waste if we were the only ones able to appreciate it.”

From Calvin and Hobbes: “I sometimes think that the surest sign that intelligent life does exist somewhere out there is that none of it has tried to contact us.”

Merv

I think the logic of something like that is dodgy – like those guys who say the earth must be young because creating all those extinct species would be a waste. You can only appreciate certain kinds of vastness if they are empty – if the Sahara were all like Las Vegas, for example.

It could be that we are called to express praise for the sheer size – or it could be that we are called to spend eternity populating it in the age to come.

My main point is that classical theology is not at serious risk either from an empty universe or a teeming universe, though the philosphical and hermeneutical presuppositions may have to change, as they have in the past.

Excellent points. Your comparison of the Sahara with Las Vegas instantly sold me on the vast emptiness! Though I suppose if I was lost and waterless in the Sahara I would probably welcome the sight of anything –even a Las Vegas if it came to it. But may it never be!

I recently switched over the desktop background on my work-computer away from a lush green landscape over to an arid and almost certainly lifeless Martian panorama. The contrast is striking –and if the desertscape had been on earth it would seem much less remarkable. But the thought of there being trillions of similar lifeless scenes scattered everywhere across the universe, waiting for something to step into it and perceive it for the first time is a staggering notion to me. Perhaps its the hopeful (from our perspective) invasion of life into such scenes that intrigues us so. But you are absolutely right that it would be depressing to travel to other worlds to find them already over-run with casinos.

My personal (as opposed to theological) fantasy may have been mentioned before here.

It’s that we make contact with some alien civilisation, hail it as the event of all times, and then find that they’re all small-minded shopkeepers who listen solely to wallpaper muzak, watch only sitcoms and are unkind to animals. And they won’t listen to correction.

And then we encounter a second civilisaton, and it’s exactly the same…

If ‘the surest sign that intelligent life does exist somewhere out there is that none of it has tried to contact us’, then attempts by us to contact life out there are not a sign of intelligence.

🙂

If we were called to spend eternity populating the universe I think we would ultimately find ourselves spread rather thinly, unless habitable zones are few and far between.

Since in the age to come “they neither marry or are given in marriage, but are like the angels” that must be where my theory begins to break down! 🙂