I continue to be intrigued by the ubiquity of evolutionary stasis as described by Donald Prothero, for example in this piece. It is the breadth and depth of his evidence that makes his case so striking, but the strapline would be:

In four of the biggest climatic-vegetational events of the last 50 million years, the mammals and birds show no noticeable change in response to changing climates.

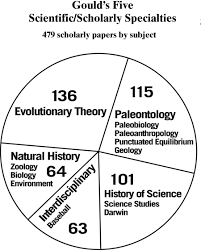

It’s vanishingly hard to find any species, amongst hundreds, that can be shown to have evolved in response to major climate change. That is a remarkable fact. Instead, he says, the large fauna migrate to stay in their ecological comfort-zone, or go extinct when they can’t. This stasis on a grand scale raises all kinds of issues, but no good explanations (according to Prothero). However, Prothero does point to the paper that really raised stasis as the “dirty secret” of palaeontology, as well as introducing the theory of punctuated equilbria to the world. This 1972 paper by Niles Eldredge (celebrated collector of trumpets) and Stephen Jay Gould (singer in the Boston Cecilia and writer on baseball) – they both did some palaeontology too – Punctuated Equilibria: an alternative to phyletic gradualism, is where I want to direct our attention today.

It’s vanishingly hard to find any species, amongst hundreds, that can be shown to have evolved in response to major climate change. That is a remarkable fact. Instead, he says, the large fauna migrate to stay in their ecological comfort-zone, or go extinct when they can’t. This stasis on a grand scale raises all kinds of issues, but no good explanations (according to Prothero). However, Prothero does point to the paper that really raised stasis as the “dirty secret” of palaeontology, as well as introducing the theory of punctuated equilbria to the world. This 1972 paper by Niles Eldredge (celebrated collector of trumpets) and Stephen Jay Gould (singer in the Boston Cecilia and writer on baseball) – they both did some palaeontology too – Punctuated Equilibria: an alternative to phyletic gradualism, is where I want to direct our attention today.

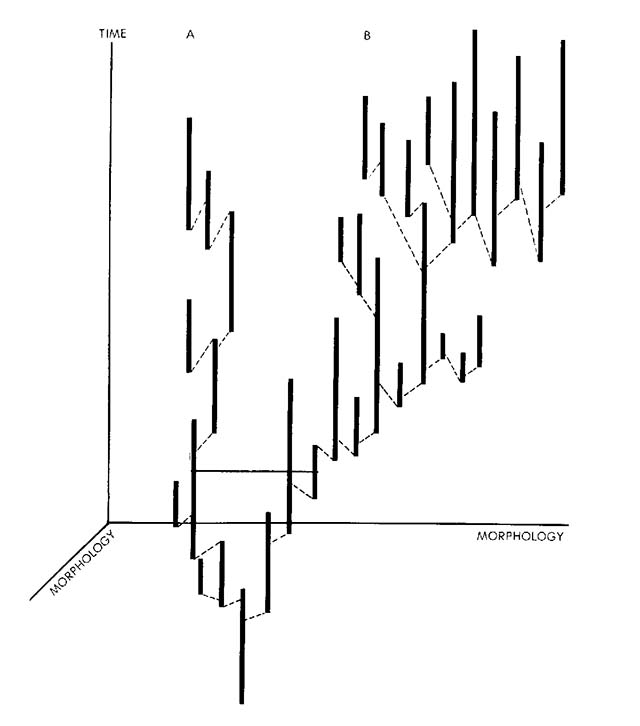

As Prothero says, this paper is a masterpiece of scientific thought, not least because it takes its philosophical presuppositions, and those of its rivals, seriously. It is sobering to think how palaeontologists, taught the Darwinian theory of phyletic gradualism, managed to impose that interpretation on the fossil evidence they uncovered for over a century, when by far the commonest pattern actually observed was stasis and saltation. Such is the power of theory.

The authors demonstrate the weakness of the relatively few test-cases of gradualism. The paper specifically cites the horse (“a luxuriant branching bush, not the ladder to one toe and big teeth that earlier authors envisioned” – Simpson, 1951); the sea-urchin Micraster senonensis (“a migrant from elsewhere… did not arise gradually from M cortestudinarium” – Nichols, 1959), and the Jurassic oyster (“the transition from Liostrea to Gryphaea was abrupt and neither genus shows any progressive change through the basal Liassic zones” – Hallam, 1959 – he says this finding matches the experience of most invertebrate palaeontologists).

By 1972, biologists had proposed for decades that the commonest mode of macroevolution was allopatric, that is a genetically-mediated speciation arising from the isolation of a small population with an atypical gene pool in a marginal evironment, providing new selective pressures. Our authors’ main contribution was to apply this existing theory to the fossil record and conclude that stasis and saltation was a real phenomenon, and why. Most evolution, they said, occurs in small, out-of-the-way corners, and on very short time scales. Although the resolution of the fossil record means speciation could take a million years and still be unobserved, they maintain that in theory most evolution will take place soon after the population is isolated, in the biological blink of an eye.

The first remarkable thing is that, although some form of allopatric speciation still seems to be the most favoured theory of speciation, gradualism is still maintained vehemently by biologists commenting on blogs like this, in popular science and in textbooks. That “ladder” of horses, for example, is still touted as a textbook example of gradualism, though Simpson debunked it before I was even born. Why is the public message so slow to respond to newer science?

Maybe the answer lies in the authors’ informed and astute observations on philosophy of science. Against so many scientistic writers of our day, they insist that theory always determines data (and remember they said this in a seminal paper a couple of generations ago: it’s scarcely novel or obscure). They cite Feyerabend’s work of just a couple of years before. They affirm Kuhn’s observation that textbooks indoctrinate each new generation of scientists in the theoretical structures that will largely determine how they view the world and its data, and specifically suggest that this is why phyletic gradualism had coloured the interpretation of the fossil record since Darwin. Indeed, they even include a telling 1861 quote from Darwin himself, showing how it undermines his later autobiographical claim to have been led only by the evidence, without imposing any theory:

About thirty years ago there was much talk that geologists ought only to observe and not theorize; and I well remember someone saying that at this rate a man might as well go into a gravel-pit and count the pebbles and describe the colours. How odd it is that anyone should not see that all observation must be for or against some view if it is to be of any service.

In winsome frankness the authors concede that the same “theory leading evidence” is true for them: as palaeontologists they have adopted the theory of phyletic gradualism, a mental construct just as Darwin’s gradualism was, because it is the current wisdom of biologists (an argument mainly from specialist authority). And they have used it as a grid on which to map the fossil evidence. Their contention is simply that their theory fits this evidence better, which is actually what good science should attempt:

The idea of punctuated equilibria is just as much a preconceived picture as that of phyletic gradualism. We readily admit our bias towards it and urge readers… to remember that our interpretations are as coloured by our preconceptions as are the claims of the champions of phyletic gradualism by theirs. We merely reiterate: (1) that one must have some picture of speciation in mind, (2) that the data of palaeontology cannot decide which picture is more adequate, and (3) that the picture of punctuated equilibria is more in accord with the process of speciation as understood by modern evolutionists.

Now, following their urging, at this point let us note the logical order here: (1) You’ve got to have some theory, (2) The fossil record doesn’t provide strong enough evidence to settle things and (3) punk eek doesn’t clash with palaeontology and fits better with the contemporary theoretical conjectures about speciation. Their theory, then, is in the end exactly as strong as the theory of allopatric speciation.

Gould’s own examples present a reasonable case for the fact of allopatric speciation – but they primarily support the case that a particular set of changes was fixed by speciation in an unusual location in “one go”, as it were. The actual evidence for the changes in Gould’s example being adaptive isn’t strong at all.

(Incidentally I recognise in this whole discussion that punk eek doesn’t invoke “hopeful monster” saltation – but nevertheless it radically compresses the concept of “gradualism” to below the resolution of paleontology. It is the underlying biological theory – allopatric speciation – that conceives gradualism where, in fact, the fossil record cannot reveal it.)

So what is the positive evidence for allopatric speciation, since Eldredge and Gould adopted it mainly as the frontrunner in current biological theory over other mechanisms like sympatric speciation?

It would appear from review articles such as that in Wikipedia that the evidence is actually rather thin: in the laboratory, Drosophila selected for particular diets apparently show “the possible first steps” to it by appearing to prefer to mate with their own populations. That’s hardly seems conclusive.

In the field, the articles reference various (mainly) sub-species of creature on different islands of archipelagoes. However, the recent doubts over the true significance of the differences between Darwin’s finches make such evidence inconclusive of one particular mechanism.

And another line of inquiry, ring species, is weakened by the gradual removal of examples (eg circumpolar gulls) from the already rather short list, just as in our authors’ own time the short list of examples of phyletic gradualism was being shown one by one to be, in the main, equally well explained by stasis-saltation, though they still populate textbooks today.

But, as they say, “one must have some picture of speciation,” even if it is biased by ones worldview. It’s worth asking what their admitted bias means in practice. At a couple of points in the paper, they reference “creation” in passing. Their worldview bias, unnoticed in the context of a “scientific paper”, appears to blind them to the possibility that they’re actually poisoning the well for alternative (theistic) theories to both phyletic gradualism and allopatric speciation:

Palaeontology supports creationism in continuing comfort, yet the imposition of Darwinism forced a new, and surely more adequate, interpretation upon old facts. Science progresses more by the introduction of new world views or “pictures” than by the steady accumulation of information.

“Surely more adequate” we’ll return to shortly. Note, though that they tacitly admit that it is their metaphysical world view, not any evidence, that alone justifies that word “surely”. Then, in discussing the unwillingness of some previous researchers to admit that humans arose from more “brutish” ancestors, they write:

Hominid catastrophism, according to Brace, is the denial of ancestral-descendant relationships among fossils, with the invocation of extinction and subsequent migrations of new populations that arose by successive creation. Such views are, of course, absurd…

They’re “absurd”, note, even though “the fossil record supports creationism in continuing comfort”. The adverbial phrase “of course” saves having to pinpoint exactly where such creationist views break down. Being interpreted, it all adds up to “we prefer not to go there.”

I guess the “world view” issue in question is the usual naturalistic one: to consider creation as an option, apart from invoking the God that Marxists like Gould wish to avoid, is to take events from the realm of explanation to the impenetrable “God did it.”

But how, in fact, does punctuated equilibria theory give us a better “explanation” in more than theoretical terms? For the suggestion, remember, is that a small sub-population of a species, that we can’t see, retreats to a small isolated environment, that we can neither detect nor, therefore, describe. Over a relatively short time a whole raft of changes occurs, invisible to the fossil record, which produce through adaptive selection (or perhaps, to incorporate today’s leading theoretical model, through neutral change) an entirely new species, which then appears fully-orbed into the light and stays substantially the same until its extinction. Note what they say about “species”:

The coherence of a species, therefore, is not maintained by interaction among its members (gene flow). It emerges rather, as an historic consequence of the species’ origin as a peripherally isolated population that acquired its own powerful homeostatic system.

In other words one real and stable species (or Aristotelian substantial form) invisibly gives rise to a different real and stable species (form).

Let’s apply this to human history, since this is one of their examples. They describe four distinct lineages: Australopithecus, Pithecanthropus (now renamed Homo erectus), Homo neanderthalis and Homo sapiens. Forty three years later that picture is pretty much the same, with other proposed taxa being in considerable doubt and even Neanderthal being shown to have interbred with us.

Yet there is still an enormous investment in filling in the gaps, in order to “explain” human evolution. But the very desire to bridge such gaps presupposes phyletic gradualism, which has been in disgrace since long before even Eldredge and Gould.

If punctuated equilibria theory is true, then it would predict that there aren’t any significant gaps in the fossil record, or at least any that we’re remotely likely to find, since none have ever been found in the entire fossil record. A small population of Australopithecines disappeared into its dark evolutionary burrow, and reappeared in the spring transformed into Peking man. Later, in another dark corner, a few of the latter disappeared to emerge as people just like us, at least as far as biology is concerned.

We ought not to find much more evidence. We can’t know anything about the environmental conditions in these dark corners, nor therefore give any adaptive explanations for mankind that aren’t pure myth-making – if, indeed, adaptation had a part to play rather than just neutral drift, which is a non-explanation.

So in fact, under punctuated equilibria we’re left with no more complete an explanation than the one our authors reject on ideological grounds – direct creation by God. To me allopatric evolution and direct creation appear to have about the same explanatory power in any particular instance, except that the latter provides a potential meaning to the emergence of man, where allopatric speciation can only shrug its shoulders and say “stuff happens”.

I’m not suggesting that this means that creation, sans mechanism, is the preferred explanation for speciation, including our own rather special case. For any such preference either depends on scientific evidence – which according to Eldredge and Gould is unlikely to be forthcoming – or on worldview – which arises from the kind of evidence in which science doesn’t, or at least shouldn’t, deal.

Suppose that God is involved directly in the coming to be of new species (we have to get to this thought eventually, even if many avoid it).

In that case, would you think it more likely that God creates new species ‘out of the dust of the ground’, or by changing a group of animals of a previous species?

If the later, I could imagine the (natural or non-natural) processes of genetic drift accumulating new genes in the unexpressed regions, and then that some internal process species-wide ‘switches them on’. This is going a long way beyond ID, because I am speculating about mechanisms, but I don’t think we should be afraid of speculations (as long as we distinguish them from facts!).

I suppose I prefer this drift+switch theory because it reduces the ‘heavy lifting’ by God. Still involvement, but back a stage into the control level rather than moving many masses.

Ian

When is a “hypothesis” not a “speculation”? So the blue-sky is a good place to start out. The empirical confirmation of many evolutionary hypotheses, including punk eek, has proved pretty elusive, I’d say, so we’re in good company.

Funnily enough I was turning over your question in my mind when walking the dog yesterday. Let’s go with the mindset of doing science in the light of God (rather that saying that an active, biblical God, curtails scientific thinking).

One then has the observation that there is, for all the discontinuity of the fossil record, a continuity usually interpreted as common descent – there is an equine or Micraster progression, rather than Eohippus disappearing and a dinosaur replacing it until a flightless bird takes over etc. God, it would seem, is doing designs in some kind of sequence, rather than simply picking them off the shelf at random. No doubt he has reasons not to create Precambrian rabbits, but the result is syill that there aren’t any.

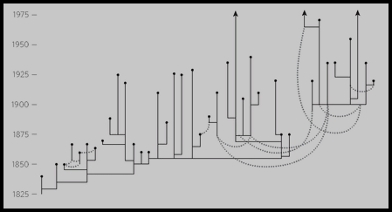

The other evidence of common descent in genetics, of course, is also apparently the most parsimonious explanation so far. Eldredge’s family tree of trumpets (above) was partly drawn to show how human design-modification produces a different pattern from what they propose for biological evolution (though it cheats a bit by assuming the absence of horizontal gene transfer and other discontinuities, in biology – evolutionary theory sees what evolutionary theory expects, just as Eldredge and Gould admit.

So without second-guessing why God would prefer to do it that way, transforming a living species in some way seems to me more likely than transforming a “Platonic form”. That makes your idea of silent transformation of the genetic background seem attractive. He has a new set of genes lined up in a small population, and he isolates it and either shuffles the genes a bit or exposes it to a selected and selective environment which does the same job…

But there’s the rub, of course, because such a process would be formally indistinguishable from random neutral drift and Darwinian evolution, apart from the human attitude to it, which would either be, “Amazing what chance can do, isn’t it?”, or “God’s providence directs what we foolishly call chance.”

When you speak of “heavy lifting”, I assume you’re not literally talking of God’s making life easy for himself, but choosing to work in a subtle way for whatever reason. The more I think about that, the less I think of the reasons usually given. For example, the Enlightenment mindset would say that God can only work through natural laws, or even that any active guidance is “interference”. We’ve all come across that. Or the idea that God hides himself because he wants willing faith rather than coerced persuasion about his existence.

All that ignores the Jewish worldview that Christ endorsed and passed on – that God’s active involvement is revealed, not concealed by creation, as it is by his governance of human history and individual lives. He’s not hiding himself, but governing his physical creation in the way that seems best to him.

So I think I’d rather go in the direction of pinning down whether there are signs of genes being, as it were, “prepared”, in which case one says, “Oh, that’s how he does it,” or not, in which case something more dramatic may in view (or in this casse, hidden in the cracks in the fossil record). The scientific program, it seems to me, can go ahead much the same, only under the banner “exploring God’s methodology” rather than “seeking a more adequate explanation than God.”

The arguments around the Darwinian paradigm will continue until something else comes along, and in view of the commitment made by atheists to the ideology, such changes will be fought tooth and nail. So I am inclined to put that to one side.

As a chemist, I am fascinated by the question of life, mainly because almost every notion of chemistry that I understand says one thing – just how improbable it is that any conceivable conditions we may imagine, in any version of our planet, could give rise to life of any type. Yet because of the mystery related to the origin of life, many scientists who adopt an atheistic (or more likely, a view that science will eventually find an answer) will continue to speculate and imagine. Such is human persistence.

Yet let us suppose that the origin of life can only be explained as an act of God. I am intrigued by the outlook we may consider in light of the science that we currently understand. Would such an act be singular and all events ‘unfold’ after that? Or would we need to go back to seeking specific points in time when we would feel God would intervene again?

I cannot put forward any suggestion one way or the other – but the mystery of life continues to intrigue us and as scientist, confound and humble us.

GD

Perhaps, given a basic biblical theology that God is involved with and governs his whole creation as a King, we don’t really need to isolate times when God acts specially in “Nature”. As the opponents of design love to say, every specific outcome in the world is vanishingly unlikely individually.

What science does is to abstract some simple principles of reproducibility from the confusion of actual events. That can be useful to help control our desired outcomes, but can seldom predicts what happens in the real world, where multiple factors interact. That is especially so in the world of life. In my Punk EeK example, even if the Eldredge-Gould theory is true, almost by definition it can’t be observed in action , nor predicted in the absence of observation. There’s no way you can look at Australopithecus and predict H. erectus, because you’ve no idea which gene pool will be isolated under what conditions. You can’t even deduce it after the event.

The Bible talks more about human affairs, but gives examples like the breakup of Solomon’s Kingdom, which although prophesied as a judgement, is described in a proper historical way (via human motivations, coincidental events etc), yet summarised as “This turn of events was from the Lord.” By implication, every turn of history that tends towards his final purposes for the world is “from him”.

Each event is highly improbable, but we take them for granted because we see familiar factors at work, including inexplicable chance (who would anticipate that a friend commenting on Sy’s US blog was an old friend from my church in UK?).

I grant that it’s hard to see a set of simple scientific principles leading to the first life – and it’s no easier to see a series of flukes doing so. But God works by both every day in our own lives. The error is to exclude him from everyday providential governance, just because we see the commonplace means he uses in action.

Jon,

In the beginning God created, and this creation continues to be sustained by God. This is a clear and unambiguous statement that we as Christians understand.

Comments and debates however, inevitably revolve about what science says, to such an extent that some talk of a ‘second’ book that may (in an inexplicable way) show us something of God. Within this context, I am suggesting that some factor(s) are so far beyond our scientific understanding (such as origin of life) that we end up facing some type of choice – do we regard something(s) as mystery, or do we speculate? A scientist will choose to speculate – yet the more I understand the natural sciences, the more I am drawn to the mystery of some central matters.

A well considered view does not cease to be such if we acknowledge that at various points, what we DO know points us to something beyond what we know (I hope that came out right).

Bumping into a friend of long ago is always a great pleasure, and one remembers that as much as the friendship itself – be it chance or otherwise.

That’s well said, and worthy of sticking above any researcher’s desk (whether a scientist, a theologian, or anything else). Legitimate speculation, I suppose, is connected to utility and worship.

The first says, “Hmm, maybe if X is true about the world I can put it to good use,” whether X is “fire is made by friction” or “gene repair saves lives.”

The second says, “This creature is beautiful, but there is even more cause for adoration when I see how it functions/ how it came into existence.”

There seems no theological reason to exclude origin of life studies from such research, though there is more empirical justification for supposing it might prove one of God’s ultimate mysteries than most other things in nature.

I think I’ve said before that I’m comfortable with the idea of “God’s two books”, but only when the true relationship of God and creation is properly understood from the actual book. Some thought on that in my next post in a day or so.

“I think I’ve said before that I’m comfortable with the idea of “God’s two books”, but only when the true relationship of God and creation is properly understood from the actual book. Some thought on that in my next post in a day or so.”

I assume by “the actual book” you mean the Bible, but maybe you’ll clarify that in your next post.

Cath Olic

Not a profound point – the Bible is literally a book, on paper, nature is metaphorically a book.