Science, we are often reassured, has absolutely nothing to say for or against the supernatural, and Christians therefore have nothing to fear from knowing more about science. That is absolutely true in principle, not least, as I have been exploring in detail here recently, because science’s methodology excludes the supernatural from its purview, “supernatural” being however defined according to arbitrary and culture-bound criteria. This is of course simply to limit science’s reach to a humanly-constrained part of reality.

But the same agnosticism and humility are not evident in the popular teaching of science, as the previous appointment of the virulently anti-religious Richard Dawkins to the chair of Public Communication of Science in Oxford showed, a pattern that is evidently reflected in most other organs of science communication.

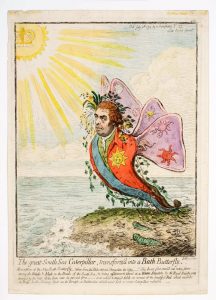

In Britain, ordinary Christians persuaded that they should embrace science more willingly are likely to start with the BBC Radio programme The Infinite Monkey Cage, in which Prof Brian Cox and comedian Robin Ince speak engagingly and often humourously about the ins and outs of science. Brian Cox is a better communicator than ever Dawkins was, having been a rock keyboardist before he was a physicist and having a more TV friendly face. A winning smile is worth several PhDs in conveying scientific authority to ordinary people – that has been the case since Joseph Banks persuaded British society, from the king downwards, that science revolved around himself.

In Britain, ordinary Christians persuaded that they should embrace science more willingly are likely to start with the BBC Radio programme The Infinite Monkey Cage, in which Prof Brian Cox and comedian Robin Ince speak engagingly and often humourously about the ins and outs of science. Brian Cox is a better communicator than ever Dawkins was, having been a rock keyboardist before he was a physicist and having a more TV friendly face. A winning smile is worth several PhDs in conveying scientific authority to ordinary people – that has been the case since Joseph Banks persuaded British society, from the king downwards, that science revolved around himself.

Cox recently hosted a special edition of the Infinite Monkey Cage on the paranormal and science, though it did not for some reason contain any disclaimer that as a “Distinguished Supporter” of the British Humanist Association, he has a religious position on such matters. It has to be said that in principle, at least, he recognises the limitations of science, as he said in a Daily Telegraph interview:

“Philosophers would rightly point out that physicists making bland and sweeping statements is naive. There is naivety in just saying there’s no God; it’s b——s,” he says. “People have thought about this. People like Leibniz and Kant. They’re not idiots. So you’ve got to at least address that.”

Nevertheless, in conversation with familiar (to US readers) guest Neil de Grasse Tyson, he demonstrated from the Large Hadron Collider that ghosts (and by implication human survival of death) have been disproven by science. The story is here. I’m still not entirely sure if the LHC gets into the story because it hasn’t actually detected spirits (raising the question of why it should be haunted anyway), or simply that it would have detected some kind of particle particularly associated with ghosts. The article quotes Cox:

Nevertheless, in conversation with familiar (to US readers) guest Neil de Grasse Tyson, he demonstrated from the Large Hadron Collider that ghosts (and by implication human survival of death) have been disproven by science. The story is here. I’m still not entirely sure if the LHC gets into the story because it hasn’t actually detected spirits (raising the question of why it should be haunted anyway), or simply that it would have detected some kind of particle particularly associated with ghosts. The article quotes Cox:

If ghosts existed, then they would need to be made purely of energy, since by their very definition they can’t be made of matter.

The idea seems to revolve around an idea that such energy must interact with matter (to be perceived by humans or empower their minds) and must be conserved according to the law of conservation of energy; and that the LHC is sensitive enough to show that no such energy escapes when someone dies. I don’t recall reading that such measurements have actually been taken on a conveniently immolated worker in the LHC, but you can see how in principle such an experiment could be set up.

But what would it prove? Only that current scientific measurement restricts itself to states for the present called “matter” and “energy”, measurements of which in closed systems lead to conclusions that they are interchangeable and conserved. Even in the standard model of physics that is not the whole truth – as far as I know gravity has yet been successfully reduced to matter or energy, and most of the universe consists of dark energy and dark matter. The LHC may or may not eventually detect the last two, but isn’t I believe set up to detect gravity waves.

Now, to speak of the “very definition” of ghosts is scarcely scientific. The first definition on a Google search says:

An apparition of a dead person which is believed to appear or become manifest to the living, typically as a nebulous image.

An apparition is definitionally a perception, implicitly of information, which would be more to do with the powers of perceiving beings (which are not in doubt) than nebulous assemblages of matter or energy, even dark matter or energy. The next definition down the search page, at Dictionary.com, does indeed add with one hand an objective aspect (soul) that it takes away with the other (imagined):

The soul of a dead person, a disembodied spirit imagined, usually as a vague, shadowy or evanescent form, as wandering among or haunting living persons.

But what is a “soul”? To the traditional Thomist it is an Aristotelian form, the pure immaterial information that specifies how the matter and energy of a person is constituted. In other words, Cox’s “scientific” dichotomy between matter and energy as the only options is simply blind to information as a primary constituent of the universe, as other physicists like Paul Davies have suggested. Davies may be wrong, but Cox’s “disproof” of ghosts and spirits is Humanist dogma, not settled science, even before we get to consider the biblical concept of “spirit”.

Now, “spirit” is no more susceptible to definition, especially scientific definition, than “ghost” (though they are, in origin, identical, if we remember “The Holy Ghost” and, even more archaically, the description of a spiritual person as “ghostly”. But in Pauline theology, “spirit” (“pneumatos“) is a principle of existence that is an alternative, and successor, to “flesh” or “soul”(psuchikos). It is closely related to the kind of existence God has, as opposed to the physical existence of the present creation, but has as its first representation on earth the spirit of man, made more manifest since the resurrection of Christ in the “spiritual man”. It cannot be perceived directly because it is more, not less, substantial than physical things – but then so, as I understand it, is dark matter.

A rough equivalent in scientific terms is that if the present age is empowered by the physical (matter/energy with their laws of conservation), human life and the age to come is governed by the spiritual (which is neither matter nor energy and about whose “conservation” we can have no idea).

With respect to Brian Cox’s debunking of ghosts, there’s actually nothing very new going on – Cox is simply denying the existence of spirit in this sense, as he personally disbelieves in the existence of God. But he’s doing so by illegitimately reducing spirit to physical energy, and than arguing from the authority of a vastly expensive piece of kit, the LHC, which most laymen and the journalist of the Telegraph biopic don’t understand at all, to back up a merely religious opinion. And he’s doing so as a scientist on a science programme, not as a Humanist on a religious programme.

Now, if the scientific community is genuinely religion-neutral, it will presumably prick up its ears at this attempt to pass off Humanistic religion as science education (many scientists listen to The Infinite Monkey Cage) and publically insist that science programmes teach science rather than metaphysics. But the story appeared a week ago now, and I’ve not seen any such rebuttal whatsoever. Certainly Neil de Grasse Tyson, a fellow astrophysicist and science communicator, made no objection after he clarified what Cox meant:

Now, if the scientific community is genuinely religion-neutral, it will presumably prick up its ears at this attempt to pass off Humanistic religion as science education (many scientists listen to The Infinite Monkey Cage) and publically insist that science programmes teach science rather than metaphysics. But the story appeared a week ago now, and I’ve not seen any such rebuttal whatsoever. Certainly Neil de Grasse Tyson, a fellow astrophysicist and science communicator, made no objection after he clarified what Cox meant:

“If I understand what you just declared, you just asserted that CERN, the European Center for Nuclear Research, disproved the existence of ghosts,” he asked. “Yes,” replied Professor Cox.

Tyson says he is an agnostic, so one might have expected him to be more of a champion for science’s agnosticism. But then he’s also on record as saying that philosophy is useless, so maybe he just doesn’t understand the issues.

As Christians we need not accept the Greek and Roman belief that there is such a thing as a disembodied soul or spirit.

Whilst many Christians think of the ‘soul’ as departing the body upon death, I think that there is scant Biblical support for the notion and a much clearer indication that when we die we do so in our entirety and have no conscious existence until the resurrection.

Perhaps this consideration is not the main subject of your post, but I make the point because Brian Cox risks deploying a straw man argument if he assumes that Christians agree with his characterization of what they think happens when a person dies.

You’re absolutely right, Peter, that disembodied souls receieve no support from the Bible. The fact that a scientific “pneumatology” is not part of the Bible’s purpose means that various views are possible, both on human and “demonic” spirits. What Brian Cox’s idea seems to have been was to pick one that nobody holds and debunk it.

Can a disembodied spirit really be a straw man, though???

The bible never mentions a single ghost. Abscent from the body is present with the lord is the old line. in fact very protestant peoples never had ghost stories. Demons witches but not ghosts. thats why the puritan yankees stories came from the Dutch Catholics .

Science , people making conclusions, does oppose the bible. organized creationism exists to fight and clobber them.

Biologus and evolutionists today are fighting a losing retreat but exist to fight.

they know they are losing.

Science is the friend of accuracy in nature and so is a creationist friend.

not a friend of human incompetence.

Robert, you wrote:

“in fact very protestant peoples never had ghost stories.”

Them’s fightin’ words, my friend!

If anything, ghost stories are much more common in Protestant countries than Catholic or Greek Orthodox ones!

The British, of course, are masters of ghost stories. One of the greatest of the British ghost story writers was Montague Rhodes James, a Cambridge man who was also one of the world’s greatest authorities on the New Testament Apocrypha, and certainly very familiar with what the Bible says in the original languages. His father was an *evangelical* Anglican clergyman. There were also Algernon Blackwood and Sheridan Le Fanu. Le Fanu was Irish, but not Catholic; his father was an Anglican (Church of Ireland) minister and his ancestors were Huguenots — as Protestant as you can get. Algernon Blackwood’s father “had appallingly narrow religious ideas” (Peter Penzoldt), which, in the context of Victorian England, almost certainly indicates some sort of strict Protestant Biblicism. So how is it that all these guys with significant Protestant background in their families wrote ghost stories?

Across the ocean, in both America (a culturally Protestant country originally) and Canada (where the English population was predominantly Protestant), there were masters of ghost stories such as Ambrose Bierce and those writers who filled *Saturday Night* journal with ghost stories in the Victoria Era. Thousands of North Americans of Protestant stock lapped up these ghost stories. Something about ghost stories has a deep appeal to Protestant sensibilities.

Apparently you think that Protestants couldn’t possibly be interested in writing or reading ghost stories, because (in your view) the Bible rules out the possibility of ghosts. But that’s taking far too mechanical a view of what religious thought is about. A ghost story writer doesn’t necessarily have to believe personally in ghosts; what the writer has to be able to do is to use ghost motifs effectively so as to weave a tale of sin, of violations of things holy, of fear and guilt associated with conscience, etc. — all themes in which Protestants have historically been very interested.

For the above reasons, your statement about Protestants and ghost stories ought to be retracted.

As for whether the Bible ever mentions a ghost, that is debatable, because there is at least one story where it *seems* as if there is a ghost — the story of the woman of Endor. Of course, the Hebrew in the passage is difficult and scholars disagree on how to interpret the story, and I’m not making any definite claim about the passage, but nonetheless, you might at least offer a modest academic qualification, such as, “With the possible exception of the story of the woman of Endor, the Bible never mentions ghosts.”

On a more Scriptural note, although the Bible doesn’t have much in the way of ghost stories, the appearance of Samuel excepted, the disciples believed in ghosts, interpreting the appearance of Jesus on the lake as “an apparition” (phantasma, in Greek).

The generic word “spirit” (pneuma) is used in Luke 24 when the disciples mistake the risen Jesus for a ghost – and interestingly, Jesus does not mock them for believing in disembodied spirits, but says that such a spirit “does not have flesh and bones, as you see I have.”

I would say that much early Protestant thinking was that ghosts might well be deceiving demons rather than “human souls not finding rest” (the latter fitted a little better with Catholic ideas of purgatory). But of course, Cox and the OP were about any kind of spiritual entity – even as Puritan a figure as John Bunyan acknowledged the potential spiritual attacks of “hobgoblins and foul fiends”.

The guys thinking there might be ghosts is not evidence there was. jUst a common error.

the bible is loudly empty of ghost because there are none. one goes straight to somewhere and no inbetween.

I think I can answer your criticisms.

Yes about Anglicans. Yet they are not of the evangelical /dissenting people. it would be accused they never held to the bible like the rest.

Later writers, you mention, are not of the protestant circle really. They came later when ghost stories became popular everywhere.

yet orginally I doubt there was allowed any ghost stories in Puritan New england. indeed Presbyterian scots/irish would also be shy but would of had a catholic heritage of ghost stories.

In america ghost stories came from the south or immigrants.

Same in canada, my country.

the witch of endor makes the case. she screamed because the prophet actually came thus concluding she was dealing with saul. it was not a ghost although they use the phrase familiar spirit. some think that means demon.

However considering the hugh amount of material on the supernatural there are no cases of ghosts. very unlike the cultures of everyone else.

this because there are no ghosts. the bible got it right being gods word.

Robert:

Remember that many Anglicans in the course of history have been very Biblical in focus, and that many have described themselves as evangelical.

Of course, if you are thinking of the Anglicans of contemporary mainstream Anglican churches, then yes, in Britain, Canada and the U.S. there are plenty of Anglicans who are “soft” on truth and authority of the Bible. But during the classic period of ghost stories the Anglican churches were more conservative than they are now, and the church services conveyed a sense of holiness that is usually missing from services now. And you have to have a deep sense of the holy and the unholy to write good ghost stories or supernatural tales of any kind.

It’s true that if you go to a typical American Episcopalian or Canadian Anglican church today you will find it filled with fluffy liberals and heavy doses of non-belief. But there are Anglican alternatives outside the “official” Anglican communions. If you are interested in what Anglicanism used to be like, you should try to find a branch of the Anglican Church in North America near you, and attend some services. They have parishes all over the USA and Canada. They still use the old Prayer Book, and if you look through the Prayer Book you will see that a massive amount of its liturgical contents are straight from the Bible. “Lord, lettest now thy servant depart in peace,” etc.

Whether or not ghost stories were allowed in Puritan New England is not necessarily an important measure of anything. The Puritans in America disallowed lots of things, especially those things that were fun or pleasurable or made the world a more beautiful, less dull and dingy place. They worshipped in plain, boxy white churches which were usually entirely devoid of any religiously inspiring artwork. (Art tends to idolatry.) Often organ music was forbidden. (Music other than hymns sung by the human voice alone tends to idolatry.) In some Puritan places in America you couldn’t even have buttons on your coat rather than hooks, because buttons might serve a decorative purpose and thus promote worldly vanity about appearance. And if you go back to the 1700s and 1800s in colonial Canada, you will find that a schoolteacher could be fired for getting his hair cut in a barber shop rather than at home by his wife. (Mustn’t let adult men associate freely with other adult men, lest, being such wicked sinners, they get into mischief! They should stay at home under the watchful eye of a virtuous Puritan wife.) So it’s not at all surprising that ghost stories, which are delightful to read, would be forbidden by Puritans.

Puritanism in America often bordered on Pharisaism, and in its emphasis on the regulation of minute matters of petty morals (don’t drink, don’t dance, don’t play cards, don’t wear long hair, etc.) came dangerously close to forgetting that Christianity was about Gospel rather than Law. I think that very few modern Christians, including quite conservative ones, would feel at all comfortable in Puritan New England, or in any place in North America where the manners and mores were under Puritan sway.

Well, enough of this. I think I’ll go now, and read a good ghost story. 🙂