A good number of studies now demonstrate that small children are predisposed to believe in God, and having a good memory of my earliest years in Beechcroft Drive I remember being no exception to the general rule. That I was made by God, and even that he knew about me and affected my life, was axiomatic to me as soon as I learned to think. This was so even though my parents were at best marginally religious and, in my earlier years, non-churchgoers – my mother’s half hearted attempts to teach me to pray at bedtime had no noticeable effect on me.

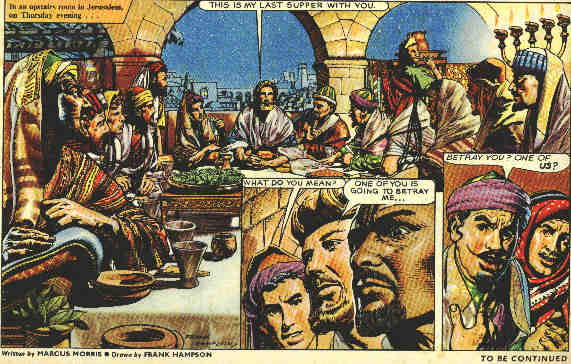

Still, my innate intuition was affirmed by society. At the age of five I was sent off to Sunday School in the vestry of the local Anglican church. At Infant School the day was topped with a Christian assembly and tailed with a prayer as we put the chairs up on the desks for the cleaner, and Miss Jerome taught us to sing that “God made little robin, in the days of spring”. At prep school I unconsciously imbibed much basic theology from the English Hymnal in school assemblies, and every Wednesday in Britain’s best comic, The Eagle, I not only kept up with Dan Dare’s astronautical adventures, but could read the strip-cartoon series about King David or Jesus on the back page. And long before Patrick Troughton became the second Dr Who I could watch him as Saul of Tarsus on BBC TV at Sunday teatimes. Even in the cubs I did my duty to God and the Queen, in theory at least.

All this is different from a living faith, of course. That I acquired from hearing the gospel for the first time at a Bible Class to which my father unwittingly encouraged me to go, but that’s another story. But I found that my new faith had to be contended for, since at Grammar School, although the English Hymnal still gave school assemblies their musical aspect, the aim of Religious Education now seemed to be to acquaint me with the Synoptic Problem and to assure me that the historical reality of Jesus’s miracles was “one theory.” That what comes of letting a vicar teach religion.

All this is different from a living faith, of course. That I acquired from hearing the gospel for the first time at a Bible Class to which my father unwittingly encouraged me to go, but that’s another story. But I found that my new faith had to be contended for, since at Grammar School, although the English Hymnal still gave school assemblies their musical aspect, the aim of Religious Education now seemed to be to acquaint me with the Synoptic Problem and to assure me that the historical reality of Jesus’s miracles was “one theory.” That what comes of letting a vicar teach religion.

I was canny enough to realise that mentioning God in an A-level zoology answer would not earn me brownie points, but I soon learned, doing Natural Sciences at Cambridge, that even the astonishing (and then quite new) discovery of the unreasonable effectiveness of the catalysts called enzymes must not be explained teleologically but in the passive (and impassive) voice considered appropriate to naturalistic biochemistry. The knowledge that even hinting at God in scientific work could lose you your job came much later, because I went into clinical medicine instead. The Christian, I guess, studies science to explore God’s creation – how bizarre that he must not be mentioned.

But even at medical school, though to most patients illness is a time when the meaning of life and death is particularly real, I learned that religion was not to be mentioned. To question the gynaecology professor about the ethics of abortion was off-limits too, even though the value of human life is a religious issue. Strangely,though, to have to sit and listen to the psychiatry lecturer blame most sexual problems on Christianity was OK (his nonsensical claim that the word “sex” comes from the Sixth Commandment on adultery – a surprise to pagan Latin authors – even made it into his textbook on psychosexual problems).

But even at medical school, though to most patients illness is a time when the meaning of life and death is particularly real, I learned that religion was not to be mentioned. To question the gynaecology professor about the ethics of abortion was off-limits too, even though the value of human life is a religious issue. Strangely,though, to have to sit and listen to the psychiatry lecturer blame most sexual problems on Christianity was OK (his nonsensical claim that the word “sex” comes from the Sixth Commandment on adultery – a surprise to pagan Latin authors – even made it into his textbook on psychosexual problems).

Actually practising medicine became increasingly difficult in the context of a Christian faith, even though that faith was the main reason for my career choice. In a Christian practice our ability to ground ethical decisions on our Christian conscience was progressively denied. First we must refer patients to another doctor with a less thought-through ethical sense than our own, and later on to a commercial clinic with no discernible ethical sense at all.

Although we were independent contractors to the NHS we were soon forbidden to advertise for like-minded Christian partners (methodological naturalism applying to employment matters, apparently), and after one NHS reorganisation we were no longer allowed even to mention our Christian commitment in patient information, because the mention of God is somehow exploitative. One heard of colleagues elsewhere being suspended by the GMC for offering to pray with patients. I occasionally ignored that rule, and in one instance the offer of prayer turned a terminal patient’s despair into hope and, shortly before his death, into saving faith. One wouldn’t want to see that kind of thing happen too often, though, in a civilised society.

I was amused that we were required, as part of our “Fundholder” contract under yet another reorganisation, to produce a “Mission Statement” according to the latest corporate fad. We actually felt we had a mission, and were sent by someone – we were called by God to be as Christ to our patients and community. But I was told in no uncertain terms that that wasn’t acceptable, so we ended up prettifying “Doing the job we’re paid for” to make it look like some unique selling point.

Alongside my career I was always a singer-songwriter. But the one unwritten rule of popular music is that whilst you may sing about politics, about incest or sado-masochism, or about imagining no heaven, you may not sing about faith in God. Or if you do, it must be so heavily encoded as to be undiscernible (“When Love comes to town…”). Because the arts are no place for religion. Religion is for irony, not celebration, even though it is God who made creativity.

Alongside my career I was always a singer-songwriter. But the one unwritten rule of popular music is that whilst you may sing about politics, about incest or sado-masochism, or about imagining no heaven, you may not sing about faith in God. Or if you do, it must be so heavily encoded as to be undiscernible (“When Love comes to town…”). Because the arts are no place for religion. Religion is for irony, not celebration, even though it is God who made creativity.

But neither is factual journalism the place for religion. As a medical columnist in a national magazine, I learned that mentioning ones religion was more than one step worse than mentioning ones children’s exploits. An entire website is devoted to showing how religion is carefully sidelined from US reporting, and it’s no different, for the most part, here in the UK. Religious news is Islamist extremism, Fundamentalists suppressing science, churches not being on-message about the newest sexual norms (or, alternatively, church people creating scandals by following those norms); not the natural human joy of worshipping and serving ones Creator in daily life.

But neither is factual journalism the place for religion. As a medical columnist in a national magazine, I learned that mentioning ones religion was more than one step worse than mentioning ones children’s exploits. An entire website is devoted to showing how religion is carefully sidelined from US reporting, and it’s no different, for the most part, here in the UK. Religious news is Islamist extremism, Fundamentalists suppressing science, churches not being on-message about the newest sexual norms (or, alternatively, church people creating scandals by following those norms); not the natural human joy of worshipping and serving ones Creator in daily life.

Politics and journalism feed off each other parasitically – especially since the Trump era – but they share the aversion to admitting God into the picture, other than the strange US stipulation that Presidents visit a church at least once before their election. But its not just that particular religions have no place in a secular and multicultural body politic, but (as Peter Berger pointed out long ago) that secular politics attempts to be omnicompetent over all of life, in the place of God.

That’s so insidious that now we can’t really imagine that there may not be complete political solutions to world poverty, to human inequalities and so on, but that some things require faith in a God beyond the power of human governments. God is the Lord of history – how then can he be irrelevant to politics? I’ve pointed out before that wherever people stand on climate change, neither politicians nor churches have called for a national day, or week, of prayer about it, but only for political action, or inaction as the case may be. Yet no human has ever managed to control the weather, whilst Christians have always believed that God does it routinely.

Secularism is insisted on in economics too – we must not let accountability to the God who provides all wealth cut across our accountability to shareholders or taxpayers. And in historical study – the Lord of history must not be mentioned as a cause in history, and even human religious motivations in the past must always be subsumed to secular motives such as power politics. In fact, in any area one cares to notice in our society, it is inappropriate to consider religion.

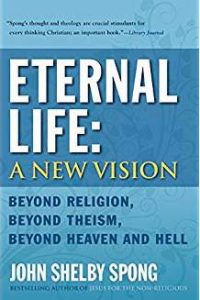

Even religion itself becomes secularised, either overtly in academic theological novelties like that of John A T Robinson or John Shelby Spong, or more subtly by becoming therapeutically aligned to human well-being rather than towards God (I notice that “pastoral work” now seems to mean helping church-members or others solve their problems, whereas the New Testament shepherd led his sheep towards Christ, and fed him with the word whilst doing so.)

Even religion itself becomes secularised, either overtly in academic theological novelties like that of John A T Robinson or John Shelby Spong, or more subtly by becoming therapeutically aligned to human well-being rather than towards God (I notice that “pastoral work” now seems to mean helping church-members or others solve their problems, whereas the New Testament shepherd led his sheep towards Christ, and fed him with the word whilst doing so.)

So every area of our Western world gives itself good reasons to leave God out of things. Our readers will be aware of the discussion both here (and here) and elsewhere about methodological naturalism in science (how easily it morphs into the metaphysical kind!). But it’s usually discussed in isolation, as if science was the only field under consideration. But when scientific secularism is seen in the context of all the other secularisms I’ve mentioned here, and more, one sees that in the end it’s all about removing religion as far as possible from the public arena.

But my problem is that I’m not secular. I’m a Christian, in every area of my life, barring my sins. I’ve seen this world as belonging God from the earliest time I can remember, and as a committed follower of the Father of us all, through his Son Jesus Christ, since I was thirteen years old. This world is the world created, indwelt and suffused by the triune God. Every part of it reflects his glory alone, and yet every part of the society in which I walk makes great efforts to exclude him from consideration, and discourages me from mentioning him, as an embarrassment or even a scandal.

So I’m undoubtedly in the world. But without any pretence of other-worldly spiritual endowments, it’s very hard to see how I can be comfortably of it.

Excellent column, Jon. This detailed biographical account is very helpful. Your description of your childhood religious life could on many points be exchanged with my own. And almost every point you make about the situation in Britain has parallels in situations across the Atlantic.

As one from the Anglican/Episcopalian tradition, I can say that the wry comments about modern Anglican/Episcopalian clerical courage in the face of secular humanism are all too often right on target. 🙂

I had the impression that Joshua Swamidass was, in addition to being a scientist, also a physician by training. I wonder if his own experience as a Christian physician has anything in common with your own. If so, perhaps it will be an appeal to his background as physician rather than as research scientist which will enable him to see the problem with “methodological naturalism.” Some of your reports about restrictions on Christian physicians ought to be downright scary to him, even if they are not as yet realities in the USA.

I can’t see how they will not eventually become US realities, given recent court rulings on same-sex marriage etc. The intelligentsia of the USA is hell-bent [pun unintentional but perhaps appropriate] on making the US a totally secular society and erasing every last vestige of Christian tradition from its public life. Someone once cracked a joke that one day Christians will be forced by law to draw their front curtains at Christmastime, lest a non-Christian walk by their house on the sidewalk and see a Christmas tree in the bay window, intruding upon secular, public sidewalk space. And if that seems too extreme to ever be a real threat, I can remember a time in the 1970s when feminists who advocated that we stop writing “craftsmanship” and start writing “craftspersonship” were laughed at [even by the majority of women] as absurdly oversensitive, ideological, and just plain silly people with too much time on their hands; now such feminists write the policy documents for universities, school boards, governments, etc.

The spirit of the modern era (as Orwell wrote long ago) is totalitarian; it’s just that the totalitarianism has changed styles in order to pretend that it is compatible with the spirit of liberal democracy. Instead of the mail-fisted totalitarianism of National Socialism or Communism, we have the velvet-gloved totalitarianism of secular humanism, whether British style, French style, or American Blue State style. But in fact hardly two American Blue State intellectuals out of ten would any longer give unqualified support to the famous statement [attributed to various people but probably first said by an American], “I may disagree with what you say but would defend to the death your right to say it.” American intellectuals are growing increasingly comfortable with the notion that sometimes it is right for the state, the university, the schools, employers, etc. to hold what people say (and think) against them and thus put well-nigh irresistible pressure (e.g., the threat of losing a job or career in one’s chosen field) upon them to conform to the current “right thinking” of the self-appointed moral or cultural elite.

And of course the current “right thinking” is feminist, deconstructionist, atheist, multicultural, Gaian, etc. — anything but Christian. That process of de-Christianizing the social ethos may be further along in Britain, but the philosophical premises now accepted by the majority of influential writers, lawyers, judges, etc. in all liberal democracies mean that eventually the same result will obtain in the USA.

I see more than a superficial parallel between “methodological naturalism” and the secular pluralist model of society. Just as “methodological naturalism” allows one to believe in God, as long as one separates out that belief in God from the way one conceptualizes nature, so the secular pluralist model of society allows people to continue to believe in God, as long as they separate that belief in God from the way they conduct themselves as members of professions, as civil servants, as parents of children in public (state) school systems, etc. You can believe whatever you want in the private recesses of your own mind, and you can worship as you like when completely out of the public eye, but you must surrender both science and social/political life to the secular humanist conception. In science you must theorize about nature as if there were no designing God, and as a parent of children in public (i.e., state) schools you must accept the premise that there are no right and wrong forms of sexuality and must accept the conditioning of your children to believe current values and conclusions regarding sexuality (and a whole range of other issues).

“Public values” now means the values urged by secularist social scientists, just as “public scientific truth” depicts a nature devoid of ends or design. A society that will punish a physician for revealing his Christian faith to his patients and a society that will deny employment or tenure to a biologist or astronomer for affirming that there is objective evidence for design in nature — these are not two different societies, but the same society seen in two different aspects.

Compartmentalization simply does not work; the public sphere is never value-neutral. To expect Christians to emasculate themselves (ooops! I just uttered an expression which the modern school system would ban as “sexist”!) politically and socially by supporting a “neutral” public sphere is absurd; if Christians remain silent about what public values should be, the society will not be “neutral”; it will be secular humanist, i.e., devoted to a non-Christian form of religion. And if Christian scientists feel compelled to automatically oppose all arguments for design in nature in order to maintain their professional “neutrality” (to be licensed for employment in universities, high schools, etc.), then their science will not be “neutral” but will become a tool for the New Atheists.

A truly neutral natural science (i.e., a natural science that does not slyly import metaphysical axioms about how nature works) would be open to the conclusion that there is objective evidence for design in nature, just as a truly neutral “health” class in a state school would be as open to arguments that some forms of sexuality are unhealthy as to arguments that all forms of sexuality are equally valid. But currently neither biological science in the one case, or social science in the other, are anywhere near neutral. They tilt massively to one side, and then have the gall to call that tilt “neutrality” and to insist that society defend that “neutral” stance against “partisan” and “religious” agendas. Only an elite dedicated to irrationality and secular humanist ideology could make such a dishonest argument. But that’s the elite that we have.

Eddie

“You can believe whatever you want in the private recesses of your own mind”

Alas, there was a time when that was true! A friend of mine was telling me about a strange dream he’d had the other day, in which a Jewish person (in some way I forget – and maybe my friend has forgotten too) treated some children somehow badly. He mentioned it as an example of the irrational world of dreams, but I had to smile and tell him that he was guilty of anti-semitic thought crime and should watch his back… I think that would have been serious and sober advice if he were at some modern universities.

But that’s not the worst of it now, in that merely belonging to a “hate group” (“white European male” being the primary one) makes one an oppressor by definition, and globally, in the best “class enemy” tradition of the Soviet era that led to the liquidation of the kulaks.

Ed Feser’s latest blog http://edwardfeser.blogspot.co.uk/2017/03/meta-bigotry.html is about the recent example of thuggish “meta-bigotry” (as he’s termed it) in the case of Charles Murray at Middlebury College. It reminded me sharply of the New Left’s fascist tactics under the guise of the Students Union and Student Opinion at Cambridge in my own day, notably against Hans Eysenck (who was only shouted down at Cambridge, but punched in the face at the LSE).

Maybe that similarity’s a small comfort, in that it’s taken over forty years for that kind of stuff to resurface, so maybe Godmay preserve us from complete meltdown even now. But even civilised secularism is an all-consuming religion which, in the end, puts society at odds with God’s reality.

Yes public values and words used in north america actually mean CONCLUSIONS. these conclusions from forceful people and these days the left wing.

The way to fight is to demand its about conclusions and who makes them and who is obedient.

In fact england today, as a canadian sees it, once again has a dissenting folk resisting the imposition of a common prayer book just like in the 1600’s.

never ends.

As a matter of incidental interest, many years ago I had regular access to a 17th century archive at Chelmsford Cathedral, which included a number of rare dissenting tracts, and included a considered response to the draft 1662 Prayer Book, most of which was in the end ignored.

It was amusing because, at that time, ultra-traditionalists were saying “Let’s get rid of this modern stuff and get back to the good old 1662 book!” It was a great window into a time of controversy, and handling first editions of Puritan Classics, and Geneva editions of Calvin and Luther, was a privilege.

A really compelling post, Jon, thanks for the candidness.

Interesting your point about physicians not being allowed to be vocal about their faith in the UK. As I think you said, it is probably spreading over here to, however slowly it may be. From experience, my dentist, my old pediatrician, and another doctor I saw once during a fit of health anxiety are all believers and quite vocal about it–in the case of the latter, he spoke to me as a brother in Christ and it had a resounding affect on me, which I credit with doing away with much of my anxiety to this point today. Private practice could have something to with it, of course; I’m not entirely sure how the law works on that point in the US, not to mention the UK. Either way, that was one of the instances where a prayer was answered directly in my life.

Several of my friends have also had their surgeons volunteer unprompted to pray for them prior to a surgery, which they almost always credit as being a huge positive.

Accidentally double-posting!

As to your point about the arts, I feel a sea-change, however small, is afoot. In 2017, a somewhat-prominent rapper (previously known for rapping mainly about pot, cigarettes and acid) released an album with overtly Christian themes. And by overtly, I mean he sampled “How Great is Our God” in a non-ironic way. He performed on SNL (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PfaKtyWlrlM) this Christmas and it was a full-blown worship show; not to mention his performance at the Grammys where he demanded of the crowd: “get up on your feet while I worship my savior”.

What’s so compelling about this is that he was decidedly not dismissed as a kook; the album was universally acclaimed as one of the best of the year, and he won 3 Grammys, all of which were in non-religous categories (which are dumb, but astounding nonetheless). Websites and magazines who are the epitome of secular were supporting him. And it doesn’t seem to be a phase for him, he’s not stopped in almost a year.

Granted, his theology is suspect and he still curses in other songs; but I’ve been floored by how the public has reacted to so positively (it helps that he releases his music for free, isn’t signed to a record label, and is a prodigy of the oft-maligned but highly influential Kanye West).

Further, indie-folk darlings Bon Iver released a weird album called 22, a Million that’s more agnostic, but entirely about the search for the divine. It’s wildly experimental (labelled “folktronica” by some), incredibly vague, but one of the most powerful albums I’ve listened to in a while. They directly quote Ps. 22, among other scriptural allusions. It too was received positively.

And finally, Martin Scorsese’s latest film, Silence, was about a couple of Jesuit priests being persecuted in Japan and this interview is all that needs to be said about it: http://www.lookingcloser.org/blog/2017/01/18/martin-scorseses-silence-a-looking-closer-interview/

I can’t recommend reading that enough.

Silence was hit with mostly positive reviews, though some were negative for reasons I suspect were religious (others not so much). It was one of my favorite films of 2016, maybe ever. One of the closing lines of the film is: “But my God was not silent; and even if he was, my life to this day would have spoken of Him”. Oof.

Noah, There probably isn’t much further secularism can go without imploding both itself and the whole society. My prayer is that genuine Christianity will get its act together rather than some ascetic form of Islam.

The problem comes when rappers sing about God, and keep on singing about pot, cigarettes, acid and the rest. This song relates!

My prayer is that genuine Christianity will get its act together rather than some ascetic form of Islam.

Can you elaborate on this a bit more? I’m unclear on what you mean.

The problem comes when rappers sing about God, and keep on singing about pot, cigarettes, acid and the rest.

Agreed; that’s Kanye West’s primary problem (and I say this as someone who admires his musical gift)–he wants to talk about God in one breath and then talk about various disgusting things the next.

Ironically, the rapper I referenced above got his big break as a featured artists on one of West’s songs–an album opener that is very religious in tone (and features Kirk Franklin!). The very next song on that album, however, opens with a very vulgar line. I’m sure someone somewhere has devised a thematic reason for it (the album as a whole is about the tension between what he wants and what he knows he needs) but it nonetheless sends a poor message.

My comment came in the context of pondering the implications of the general fact that most of the movers and shakers in art (which is driven by cultural prejudices, no doubt) are non-Christians. Since art isn’t an independent exercise, this isn’t troubling but since even hardened secularists acknowledge the beauty of Bach’s music or Da Vinci’s paintings I can’t help but conclude that we’ve surrendered art, in part, to secular society and retreated to our own echo-chamber, where we mistake “Christian rock” for being an ideal and “faith-based films” for actually being meaningful contributions to cinematic history.

I don’t mean to assert that Christians aren’t at all making good art–look at Scorsese, (maybe) Terrence Malick, one Sufjan Stevens (a truly adventurous and profound musician), among others I’m sure I’m forgetting. And I’m well aware that overtly Christian art is probably not going to get its fair shake in public discourse (Silence was victim to this); but as it stands it seems that art has been wrestled from our grasp. Perhaps this is too pessimistic, though.

And a great song, by the way! That riff is phenomenal.

Noah

Thanks for the compliment. Jethro Tull meets the Stranglers. Although I was never “signed”, the attempt to do non-religious music christianly was always very much part of my aim, and it came from various friends back in the early seventies trying to address the “Christian art” deficit.

One in particular was John Russell, a pretty competent guitarist from my home town determined to bring Christian witness and content into the secular music business. To an extent he succeeded, in that his band After the Fire had a top 10 hit in the US in 1983. He’s now in a band with another mate I toured with in the early 70s, as well as occasionally playing with an acoustic version of ATF.

Incidentally ATF’s vocalist had also been at my school, and went on to become music director of Holy Trinity Brompton at the start of the Alpha Course development.

“Christian Rock” never really took off here. Part of that may be economic: there was never really enough money in the church system even to support Graham Kendrick and a few folk bands back in the day, and the commercial companies don’t see it as a marketable genre.

My point on Islam was also influenced by a friend, my former pastor, who considered that we’ll eventually become so sated with secular hedonism that some form of ascetic religion may become fashionable. Currently the ongoing animus against Christianity, the lack of any real Evangelical resistance to hedonism and the media’s tendency to “respect” Islam (and especially its ability to swim against the tide of secularism) may lead more people to embrace it.

Living the gospel will be the best antidote to that.