One more post – probably the last for now – on some of the seldom remarked ills of modernism. And this one is about how we have fallen for that comic inversion of the East London tailor’s adage: “Never mind the quality – feel the width”. As so often in these blogs, it was the juxtaposition of two experiences that set me thinking.

The first was the reading of a biography of Captain Cook. And jolly good it was too. The second was playing around with Google Earth, following a bit of family history research with my wife, during which I sought out the house where she first lived, which she hasn’t seen again since infancy.

After I found it on the aerial, and then street, views, I panned out to see how close it was to Heathrow Airport (very close, explaining, perhaps, why my brother-in-law became a pilot!). Next I idly flew across London to our first flat in Vauxhall, then boldly across country to see my own childhood haunts in Surrey, and quickly across to Essex to where I lived until eight years ago (pleased to see how the front hedge I planted has matured). I even found a small corner shop in Birmingham which still exists a century after my great-grandmother last kept it.

I zoomed out rather too far after that and found myself looking at the whole earth from space (a flick of the mouse made it night, and it was quite fun repeatedly switching the day on and off), so I decided I might as well drop in to see what kind of house a correspondent of mine in Sri Lanka lives in. Curiosity satisfied I ended up at the lake in South Island, New Zealand, which we visited before I retired, and was gratified to see the seaplane we hired still on its moorings. I could easily have dropped in on you (we have regular visitors on The Hump from over 30 countries – though I’m really not sure why we’re so big in Sweden).

What a small world we have – no bigger, in fact, than my monitor. One certainly gets a sense of godlike power and knowledge, snooping on neighbours across the globe, especially now that the program will transition from the familiar “satellite” views, through oblique vistas that give one a good view of the back gardens of ones childhood play, to the street views with their Coca-Cola signs and ubiquitous concrete apartment blocks. Except for Jos, Nigeria (where my father convalesced in 1944), which also has a smattering of traditional mud buildings. Jos, Cos or Fosse Way – it’s all one to Google Earth.

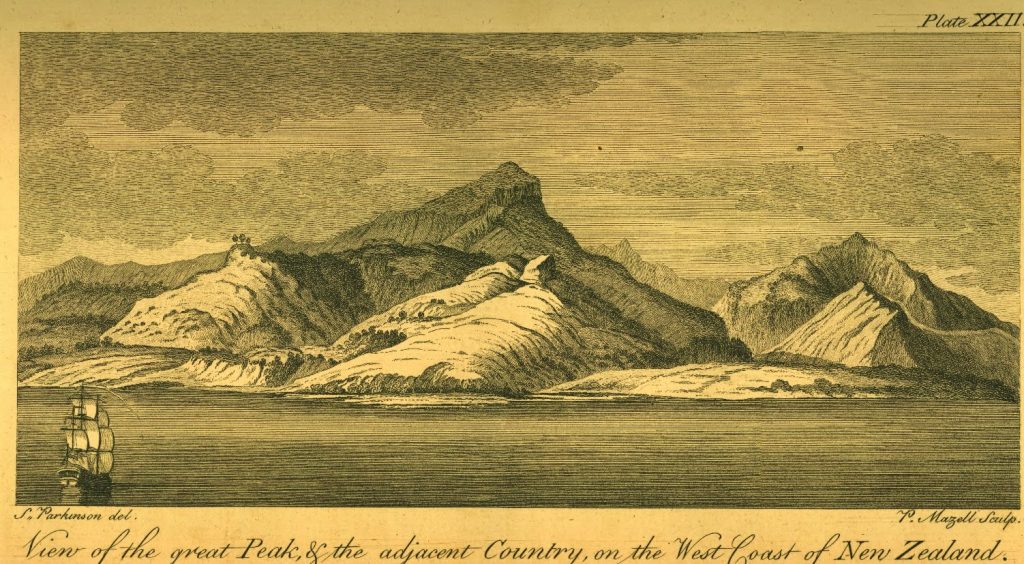

It was whilst “in” New Zealand that I remembered Captain Cook, labouring through Cape Horn storms, disease and hostile encounters for a couple of years until he could chart the coast, at least, west of Lake Te Anau. Did my half-hour digital jaunt bear any relation to his voyages of exploration?

In important ways it did not. I saw the houses of friends – but I didn’t meet my friends. The illusion of reality also wore thin, like some glitch in the Matrix, from time to time. Why, for example, were those trees round my old house clearly mere computer graphics for a few seconds before they became realistic – as if I’d stumbled upon some thin portion of an illusory world before the Agents sorted things out? Well, actually, because I’d stumbled upon some thin portion of an illusory world. That also explains the odd fact that the cars in the aerial view of our house mysteriously morphed into the cars we had eight years ago, when I zoomed into street view.

Now Google Earth is, of course, only a useful tool, even if it does give one a sense of personal deity. Still, it makes the whole world look very small and accessible, and even out in the real modern world that’s the case nowadays. I reached Te Anau for real by three plane flights and a morning’s drive in a hire car. I missed India on the way, but on the flight back awoke from my slumber for long enough to see a couple of lights from it through the clouds before drifting off. I’ve done India, me, and Captain Cook never got there.

But even Cook’s voyages, heroic epics that they were, barely sketched the coastlines of vast lands. The original Aborigine and Polynesian settlers, seeking new homes in a vast ocean in their tiny slow canoes, must have had an even greater sense of the real size of the world than the crew of a Royal Navy brig. For in spite of global villages and Google Earth, we understand the world, and its relation to us, only as we meet it face to face, and preferably on foot, rather than as we fly high above it in actual or virtual reality.

I first discovered that truth when my wife and I (and our bearded collie, Scruffy) walked the prehistoric ridgeways of southern England. Many of the significant sites we’d seen before, travelling by car from A to B. But walking steadily for several days toward a distant goal we came to know the path, the topography, the different geological “atmospheres”, the atmosphere itself as weather systems wheeled by, the wild plants, the animals and, of course, the people we met and had time to share ourselves with minus any agenda.

It’s almost as if, walking across the world for which we were created, one has Martin Buber’s kind of “I-thou” relationship to it, rather than what you get in jetting to a destination for a conference or a holiday, which is much more an “I-it” relationship.

Is that romantic fantasy? I’m not sure that it is. Natural theology aside, I believe the physical world is at the deepest level a kind of communication of the Father to us, spoken through his creative Word, Christ, and no doubt mediated to our hearts by the same Spirit who hovered over the face of the deep at the beginning. The Romantic poets like Wordsworth were wrong to equate “Nature” with God, but the love of God is nevertheless immanent in what he has made, as orthodox believers like Thomas Traherne appreciated. We’re blind to that love in creation, of course, if we only see the world as processes to be understood or, worse still, as resources to be manipulated and exploited to our will.

But we are also in danger of losing the world, along with our soul, if we buy even partially into the myth that it can be reduced to abstractions or apps, however sophisticated the algorithms may be.