One product (literally) of genetic determinism (and incidentally another that was, like molecular biology and eugenics, massively funded by the Rockefeller Foundation) is genetically modified seed. Twenty years ago, my son was at college studying aquaculture, and I used to argue with him about GM, which to him was simply a targeted improvement on selective breeding, but to me a potential ecological disaster because of our ignorance of how the genome actually works. He was evidently taught the hubristic reductionist version of genetics I discussed in my recent post.

I wrote a couple of years ago about how I felt increasing knowledge was making my fears more focused and realistic. I didn’t actually mention the Human Genome Project, but the results of that were in the background. The mantra that “one gene -> one protein” is now completely defunct, and the seldom mentioned fact that there is still an almost complete epistemological divorce between the details of genotype and the details of phenotype drives that home. In life, the genome interacts with the epigenome and a plethora of other “-nomes” including (I kid you not) the “unknome” (does that not somehow remind you of St Paul in Athens, seeing the altar to the “unknown god” which showed the Greeks didn’t know any real God?).

So if genetic modification, by inserting a few genes specifying pest resistance or glycophosphate tolerance, were to work in a trouble-free way, it would not be parallel to selective breeding of natural forms at all, but to inserting a kind of prosthetic limb which, by luck, turned out not to cause allergic reactions or electric shocks to the wearer. In other words, these genes would not be functioning as a true part of the mutually interactive  organism at all. The biggest dangers would come from their beginning to do so in unanticipated ways, through the organism’s astonishing resources of alternative splicing, reverse transcription, differential expression, control networks and so on. These interactions are what has prevented the HGP revolutionising medicine in the anticipated way and, instead, launched a host of new research programs into the previously unsuspected multi-level complexities of real, as opposed to reductionist, genetics.

organism at all. The biggest dangers would come from their beginning to do so in unanticipated ways, through the organism’s astonishing resources of alternative splicing, reverse transcription, differential expression, control networks and so on. These interactions are what has prevented the HGP revolutionising medicine in the anticipated way and, instead, launched a host of new research programs into the previously unsuspected multi-level complexities of real, as opposed to reductionist, genetics.

In fact, the biggest problems with genetically deterministic GM have come from left-field of my fears, from the utterly conventional genetics of natural plants in the farming environment. So far, pest-resistance in developing-world GM seems to be on target in increasing yields and making farmers economically dependent on Monsanto, all according to plan. But in America, as a New York Times piece documented last year, the promise of greatly increased yields and reduced pesticide use has entirely, and expensively, failed. Instead the USA has seen a massive increase in all pesticides because of the simple selection of resistant weeds, through overuse of chemicals.

The most telling part of the NYT piece, to me, is the fact that, whilst in the US, herbicide use showed only a slight, initial, dip when GM crops were introduced, followed by a sharp and progressive rise and a modest increase in yields, in Europe, where the Luddites won out and GM is still banned, yields have increased far more, and herbicide use has dropped progressively.

Monsanto has done OK because it makes the herbicides as well as the seeds, but one might have expected that the wider scientific community ought to have cast widespread doubt, in advance, on a strategy that intentionally obliterates any kind of ecosystem to produce a crop monoculture. “Nature gets in our way, Nature don’t feel so well”. Life being full of surprises, though, the geneticists didn’t predict that simple, and in retrospect obvious, problem of weed resistance. So why did we accept their assurances that fears of far more profound and subtle problems were mere anti-science scaremongering? Why do we still do so?

Monsanto has done OK because it makes the herbicides as well as the seeds, but one might have expected that the wider scientific community ought to have cast widespread doubt, in advance, on a strategy that intentionally obliterates any kind of ecosystem to produce a crop monoculture. “Nature gets in our way, Nature don’t feel so well”. Life being full of surprises, though, the geneticists didn’t predict that simple, and in retrospect obvious, problem of weed resistance. So why did we accept their assurances that fears of far more profound and subtle problems were mere anti-science scaremongering? Why do we still do so?

Maybe the answer is that the HGP results weren’t then in, and they were a surprise to everybody except the lunatic fringe who thought a reductionist, piecemeal approach to genetics couldn’t possibly explain the whole of life. What some of them thought, and what the HGP now confirms, is that life must be treated as an emergent phenomenon.

By this I don’t mean the kind of emergent theories that suggest increasing complexity automatically produces something for nothing. These are only really, as far as I can tell, an ambitious variety of reductionism, of the kind that assumes that sticking enough computers together will make a conscious mind, or that an entropically open energy system will generate mankind and all his works, “just like that”. In fact, though, linking computers does not even make a world wide web until someone clever wants it and finds ways to make it work.

By this I don’t mean the kind of emergent theories that suggest increasing complexity automatically produces something for nothing. These are only really, as far as I can tell, an ambitious variety of reductionism, of the kind that assumes that sticking enough computers together will make a conscious mind, or that an entropically open energy system will generate mankind and all his works, “just like that”. In fact, though, linking computers does not even make a world wide web until someone clever wants it and finds ways to make it work.

No, emergence is about complexity producing possibilities or even conditional necessities that could not be predicted from the simpler state, provided someone or something instantiates them. Thus complex human organisations cannot be predicted from nuclear families, and it’s tempting to think they happen automatically, “by emergence”. But they don’t – each member of such a complex society is a humanly (rather than mechanically) intelligent being contributing to the adjustment to novelty. And so a house church of eight people, managed without visible leadership, requires an eldership as it grows, a full-time leader or two and fixed roles as it grows more, a bishop if it fills a city and (maybe!) a Pope and curia (or an elected president and general assembly) if it fills the world.

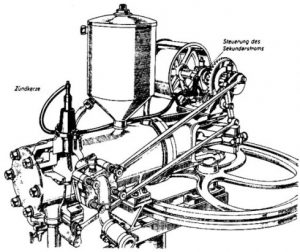

Now, if I wanted to go back in time and teach Isaac Newton how cars work, I could start by explaining Karl Benz’s original engine, and work through automobile history incrementally up to the computer era (when even skilled mechanics lost the plot!). I could do that because cars are built on reductionist principles. Emergence doesn’t play any real part.

Now, if I wanted to go back in time and teach Isaac Newton how cars work, I could start by explaining Karl Benz’s original engine, and work through automobile history incrementally up to the computer era (when even skilled mechanics lost the plot!). I could do that because cars are built on reductionist principles. Emergence doesn’t play any real part.

But that doesn’t apply to understanding, say, how the Roman Catholic Church works as an organisation. Looking at a small Catholic congregation in Mexico wouldn’t help much. Nor would investigating how the house-fellowship of St Paul’s Colossae functioned  explain the entirety. Each congregation has to explore, or copy, new solutions to the problems of growth, as my own church has recently been finding. Probably the only way to make sense of modern Catholicism (or whatever other human organisation you might name) is to live within it over a long period, until what it is is known to you in a kind of Goethian gestalt way. Prediction from the constituent parts is a lost cause.

explain the entirety. Each congregation has to explore, or copy, new solutions to the problems of growth, as my own church has recently been finding. Probably the only way to make sense of modern Catholicism (or whatever other human organisation you might name) is to live within it over a long period, until what it is is known to you in a kind of Goethian gestalt way. Prediction from the constituent parts is a lost cause.

That brings me to my last point, which is that, almost inevitably, the old reductionist genetic determism has been associated with an evolutionary approach to research. It was, famously, Theodosius Dobzhansky who wrote, “Nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution”, and he was one of the first of the Rockefeller-funded geneticists kick-starting the field of molecular biology. The quote was actually part of an affirmation of a theistic evolution, in a kind of “non-overlapping magisteria” context. But the scientific thought underlying it was surely that the understanding of how life works can only come about by exploring its past progression from simple constituents to the complex present, just like Newton’s understanding of the motor-car grew (in my imaginary scheme) from looking at the development of its constituent parts over time.

But if life is, as the Human Genome Project demonstrates, not the sum of its constituent molecular parts but a highly emergent phenomenon, in the sense I’ve described, then such an approach may be totally mistaken. As Richard Lewontin wrote in 2011:

One of the ironies of language is that we use the term “organic” to imply a complex functional feedback and interaction of parts characteristic of living “organisms.” But musical organs, from which the word was adopted, have none of the complex feedback interactions that organisms possess. Indeed the most complex musical organ has multiple keyboards, pedal arrays, and a huge array of stops precisely so that different notes with different timbres can be played simultaneously and independently.

Or to quote Ian Anderson of Jethro Tull out of context: “I don’t believe you – you have the whole damn thing all wrong.”

Might it not be that the study of the simple components of life, whether as they exist currently or as they change evolutionarily, has no fundamental connection with how living things actually function, because that depends on emergent phenomena of at least as much complexity as those of human institutions? If that were the case, then all the research emphasis on evolution would make no more sense than sinking fortunes in hiring archaeologists to solve the world’s social problems.

Evolutionary science, then, appears to be very much a product of reductionist thinking, and far from being the only thing that makes sense of it, may simply be getting in the way of an understanding of biology.

Finally, if you have half an hour spare, immerse yourself in Steve Reich’s masterly analysis of reductionist science. If you’ve an hour, then search YouTube for the other two tales and ponder the whole character of our times!