This year’s BioLogos conference was addressed by N T Wright, and his talk was praised by Hump writer Sy Garte on his own website. A clip, basically showing that one might expect an evolutionary process if one sees Christ as the creative Logos of God, appeared later at BioLogos. You can see the four minute clip here.

It’s hard to be sure of his total message from such a short clip. From what I know of Wright from elsewhere, I take it his aim was to justify a broad evolutionary understanding of world history against an over-literal interpretation of Genesis 1, and no more. Apologetics for Creationists would be an obvious motive for BioLogos to use this extract.

Other important aspects of Wright’s outlook are barely hinted. For example, he mentions Epicurus in a passing comment, and I have heard him elsewhere wax eloquent against undirected chance in evolution, which he terms “Epicureanism” and attributes to Charles Darwin (though in the clip only mentioning it connection with Erasmus Darwin, his grandfather). By no means all Evolutionary Creation advocates would see eye to eye with him on that.

To summarise part of his argument rather inadequately (take 4 minutes to look at the clip!), he says that one would expect that since creation occurs through and for Christ, its manner would be likely to match the character of Christ revealed in his earthly ministry and since, such as the Kingdom which grows without violence from a mere mustard seed to fill the world, often seeming invisible, messy and surrounded by chaos.

That makes some sense to me, for Jesus is also the Lord of human history, moving it (as we learn from books like Daniel and Revelation) towards its allotted climax, yet against the backdrop of often invisible progress, messiness and apparent chaos. Likewise his involvement in our personal lives often takes us in mysterious ways – or permits us to stray into mysterious ways of our own for lengthy periods.

And yet it’s always dangerous to judge how things in the world must be on the basis of what we believe about the nature of God, simply because we don’t know as much as we think, and what we do know is always coloured by our culture. For example, in a society where smacking a naughty child is an open and shut case of abusive violence, it seems implausible that the Father would raise up the Babylonians to destroy the whole kingdom of Judah violently. Yet the prophets say he did.

I just want to pick up on one thing Wright said in this connection because it touched a nerve from previous conversations, and that was his contrasting of the way Jesus would work in creation with the manner of an “Oriental Despot”, clapping his hands (and chopping off those of others) to procure absolute and instant obedience. Now like many I’m a big fan, with a few reservations, of Tom Wright’s theological approach, and it’s usually carefully nuanced, but liable to misunderstanding of one hasn’t read the nuancing passage elsewhere! If by “oriental despot” he meant a proverbial Chinese Emperor ruling monomaniacally, then I totally agree.

I just want to pick up on one thing Wright said in this connection because it touched a nerve from previous conversations, and that was his contrasting of the way Jesus would work in creation with the manner of an “Oriental Despot”, clapping his hands (and chopping off those of others) to procure absolute and instant obedience. Now like many I’m a big fan, with a few reservations, of Tom Wright’s theological approach, and it’s usually carefully nuanced, but liable to misunderstanding of one hasn’t read the nuancing passage elsewhere! If by “oriental despot” he meant a proverbial Chinese Emperor ruling monomaniacally, then I totally agree.

But I was prompted to object to the same metaphor on a previous occasion five years ago, when it was used by Open Theists to overturn the sovereignty of God as revealed in Scripture, with the suggestion that Scripture itself took its view of God erroneously from the absolute monarchs of its own world. And with the caveat that Wright in all likelihood has no truck with such an idea, I want to argue that, in fact, the biblical view of God’s rule is radically different from the experience of ANE kingship, and that though the latter historically did form the basis of pagan religion, because of that inadequate model, it resulted in a debased view of divine sovereignty.

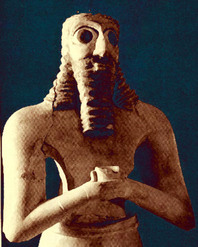

In his classic On the Reliability of the Old Testament Kenneth Kitchen has a section describing the rise of Mesopotamian civilization and religion. It seems the earliest gods of which we have record had responsibility over, and only over, their particular realm – the sun, the wind, crops, or whatever. Their only true forms were the forms of those things – which means that when you looked at the moon, or the ocean you were seeing the god manifested. If you happened to be the god of the something invisible like the wind, that was just tough.

The chief and father of the gods was Anu, the god of heaven, so who knows whether it’s possible that this early pantheon arose from the kind of corrupted knowledge of the true God Paul describes in Romans 1.20 (cf Ps 19 – though that is far too late to be a direct commentary on any such decline from a primordial true religion)? Don Richardson’s Christian classic, Eternity in their Hearts, describes how many primitive cultures still retain the idea of a supreme sky god, often deemed beyond human knowledge, so the idea is not impossible.

The chief and father of the gods was Anu, the god of heaven, so who knows whether it’s possible that this early pantheon arose from the kind of corrupted knowledge of the true God Paul describes in Romans 1.20 (cf Ps 19 – though that is far too late to be a direct commentary on any such decline from a primordial true religion)? Don Richardson’s Christian classic, Eternity in their Hearts, describes how many primitive cultures still retain the idea of a supreme sky god, often deemed beyond human knowledge, so the idea is not impossible.

What is the case is that this phase more or less coincides with the first cities we know of in the world. Kitchen describes how, at first, co-operative urban communites like Eridu or the biblical Enoch were governed by representative councils. But soon the problems this caused led to the first of the Sumerian kings arising to bring an order that was regarded so highly that it was referred to as the time that “kingship descended from heaven (= anu)”.

Now, the point is that, from its very start, kingship was in practice dogged by all the human weaknesses and vices that figure in all our political institutions. Machiavelli didn’t invent the canny ruler struggling to maintain his rule by any and every means. Rulers might be, and regularly were, ousted or murdered by jealous relations or even their own children. Dynasties might succumb to rebellion. In the case of ancient Sumer, the kings ruled individual cities vying for prosperity amidst scant resources, and pretty soon for dominance of the wider region. A prime example of this, in later millennia, was the Empire of Assyria, which had once been the city state of Asshur, which city was eventually replaced with Nineveh, becoming the religious centre only.

Kings, it is true, had great personal power and wealth, but it was always limited religiously by their duty to the ruling deity of their city to govern well (mediated by powerful priests and pernickity prophets), and practically by the fact that even the greatest emperor can be assassinated, as was King Hezekiah’s nemesis Sennacherib, or defeated in battle, like Nabonidus of Babylon. The real picture of royalty can be read in the Old Testament Books of Kings.

Now, it was this experience of human power that came to be attributed to the Mesopotamian gods. They began to be seen, like their cities, as territorial, dynastic and competitive. Accordingly their cosmic functions get much harder to pin down, being sometimes accumulated so as to be as varied as a mediaeval churchman’s benefices, and as loosely connected to work actually done. Anu, in effect, delegated his work and was promoted out of any effective role. By the time we get to a late text like Enuma Elish the work of gods is much like the Game of Thrones. This work, once considered a counterpart of the Genesis creation, is now realised to be, in essence, a dynastic struggle in which Babylon’s deity Marduk gets to be leader of the gods, in tandem with Babylon’s becoming an empire, if it dates to Hammurabi’s period as many think.

So ANE kingship did provide a picture of deity – and it was the fragmented and humanly fallible picture that is typical of polytheistic systems. Later generations of Mesopotamians even looked back to the simple, nameless gods of the time before cities, quietly getting on with their respective jobs, as a golden age in which men, too, lived in harmony and spoke one tongue (a literary parallel to the Genesis story of Babel).

In the midst of this, the absolute sovereignty of the God of Israel, who “acts, and who can prevent it” (Isa 43.13), and whose “plans stand firm forever” (Ps 33) is not after all a reflection of any oriental potentate real or imagined, but something entirely above the human realm of politics. He bursts into history (so to speak) in Genesis 1 in marked contrast to any cosmogony or cosmology that existed elsewhere. His power (and his love, and his faithfulness and all his other attributes) are unique. And that is, to a large extent, why the God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob is still worshipped across most of the world, whilst the battling deities of Babylon or Egypt, and bloodthirsty tyrants like Chemosh and Milkom, are forgotten apart from their role in horror movies and internet cults.

Now, how such a picture of absolute sovereignty fits into what our Lord Jesus Christ reveals about God from his earthly ministry requires much careful work. A kind of despotism seems to be entailed by strict monotheism, and perhaps it is the revelation of the triune nature of God which qualifies that. At the same time it’s worth remembering that both the disciples and the New Testament writers repeatedly use the word “despotes” of Jesus, and even in Greek it still means “one who possesses supreme and absolute authority”. So it may be that our cultural aversion to the exercise of power may need to be modified in building our picture of Christ.

In any case, let us consider carefully what the Bible says about the sovereignty of God, because it doesn’t derive from any transfer of imagery from oriental despots, but from Israel’s experience of the One who put those earthly rulers in their place.