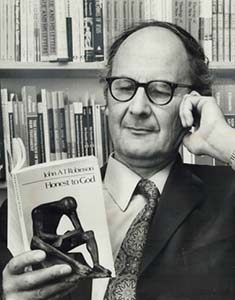

This post is an occasional (and I feel necessary) return to the concept, fielded by Christian sociologist Peter Berger, of the difference between the “credible” and the “plausible”, sociologically speaking. I can illustrate this from my recent recollection of Bishop John Robinson’s book, Honest to God.

The bodily resurrection of Jesus is a unique event, and a unique claim, in all history. It is therefore equally credible, or incredible, at all times. Faith in it will always depend on specific factors, such as trust in the truthfulness of the witnesses and the witness of the Holy Spirit to the heart. But to Robinson, in the particular culture or subculture he inhabited (“the cathedral close of his Canterbury boyhood, of the public school and university of his youth, of the cloistered college of his training, and of the Cambridge of his earlier career”), such a claim, like the Virgin Birth, was no longer worthy even of serious consideration. Educated “modern man” simply could not countenance it, and therefore Christian teaching had to change. The book was a best-seller in the sixties because that claim seemed true to many even within the churches.

The bodily resurrection of Jesus is a unique event, and a unique claim, in all history. It is therefore equally credible, or incredible, at all times. Faith in it will always depend on specific factors, such as trust in the truthfulness of the witnesses and the witness of the Holy Spirit to the heart. But to Robinson, in the particular culture or subculture he inhabited (“the cathedral close of his Canterbury boyhood, of the public school and university of his youth, of the cloistered college of his training, and of the Cambridge of his earlier career”), such a claim, like the Virgin Birth, was no longer worthy even of serious consideration. Educated “modern man” simply could not countenance it, and therefore Christian teaching had to change. The book was a best-seller in the sixties because that claim seemed true to many even within the churches.

In fact, Robinson doesn’t even attempt to deal with the Resurrection specifically. As N T Wright writes, in a retrospective:

There seems to be, in fact, no theology of Revelation at all in the book, except in the most downgraded sense of natural theology (‘what people today find credible’; ‘the exhilarating and dangerous secular strivings of our day’); just as there is no theology, or even account, of Resurrection, not even an attempt to explain Easter away in a naturalistic fashion. Robinson had already suggested, in The Body, that the church itself is the real resurrection body of Jesus; perhaps his experience as a bishop had rendered this proposal problematic.

And yet, as I have noted for a number of years, whilst belief in the Resurrection may have actually diminished since then because there are fewer Christians, the possibility of its truth is greater now: “public” spirituality became more open to the supernatural through things like the New Age movement and Eastern religion, and within the churches the Charismatic movement, even when not embraced, changed the temperature to the extent that even believers of a scientistic bent – who reject any divine intervention in nature – tend to be pretty comfortable with the Resurrection. A generation or two ago, they would have been assailed by doubts that it was intellectually viable to accept it (even without reading Honest to God) – and yet before, during and afterwards, the raising of Christ remained an impossibility that God either performed, or didn’t: its credibility never changed.

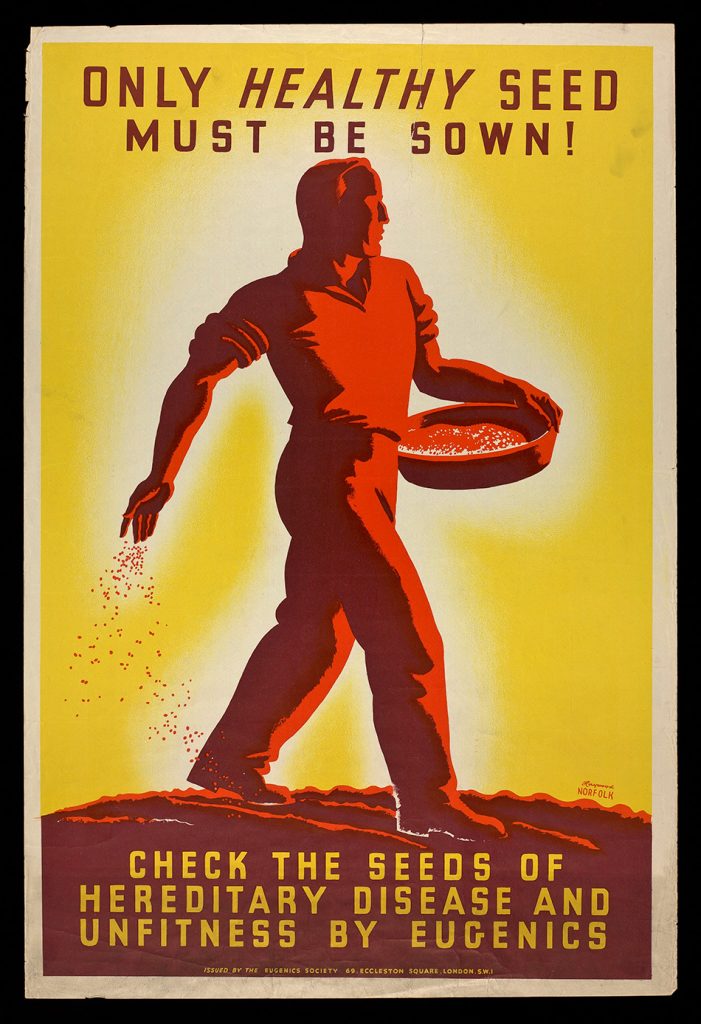

The difference between the times is the difference in plausibility, and that in the end depends on the zeitgeist in ones culture to which one tends unconsciously to conform. What factors produce that zeitgeist is another matter – they could include mere fashions in ideas; they might be deliberately cultivated by pressure groups, mass propaganda and (who knows?) global conspiracies by shadowy manipulators; they certainly, as Robinson demonstrates, become perpetutated and authorised by academic conceit.

For Robinson, circulating in an academy, and in a liberally-dominated church educated in that academy, simply assumed that his kind of people were “modern man”, and that they had an incontrovertible right to define that creature. He couldn’t conceive that, for example, a recently converted teenager like me, bright enough to be on his way to Cambridge soon, might have a valid, but quite different, worldview – once I was “properly educated” I would see the error of my ways by understanding how there is no going back after the Enlightenment, and would appreciate the need to reformulate Christianity. Except that in the event I never did see that light, and Enlightenment values eventually went out of fashion. Few nowadays could read Honest to God without considering it passé.

But the change in plausibility structures has occured only in the details – the underlying principle of conforming to worldview fashion, rather than grappling with credibility itself, remains the same. That came home to me last week when the “unreformed Marxist” (as my wife’s Soviet historian cousin dubs him) Jeremy Corbyn, the leader of the Labour Party defeated the week before in a general election, drew a larger and more enthusiastic crowd than Foo Fighters at the prestigious Glastonbury Festival.

But the change in plausibility structures has occured only in the details – the underlying principle of conforming to worldview fashion, rather than grappling with credibility itself, remains the same. That came home to me last week when the “unreformed Marxist” (as my wife’s Soviet historian cousin dubs him) Jeremy Corbyn, the leader of the Labour Party defeated the week before in a general election, drew a larger and more enthusiastic crowd than Foo Fighters at the prestigious Glastonbury Festival.

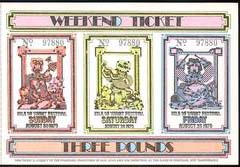

Now in 1970 I paid £3 of my Scientific Assistant earnings for a three-day ticket to the Isle of Wight Festival, camped in primitive conditions and enjoyed most of the best names in the music scene then, including Jimi Hendrix, Jethro Tull, Joni Mitchell, the Who… The event was famously somewhat marred by violent left wing protestors from Europe, more or less slitting the throat of the always illusory utopian vision of Woodstock. Somehow a local Evangelist was invited to speak briefly on the Sunday, and was jeered with cries of “What about freedom of speech?”

Now in 1970 I paid £3 of my Scientific Assistant earnings for a three-day ticket to the Isle of Wight Festival, camped in primitive conditions and enjoyed most of the best names in the music scene then, including Jimi Hendrix, Jethro Tull, Joni Mitchell, the Who… The event was famously somewhat marred by violent left wing protestors from Europe, more or less slitting the throat of the always illusory utopian vision of Woodstock. Somehow a local Evangelist was invited to speak briefly on the Sunday, and was jeered with cries of “What about freedom of speech?”

Glastonbury Festival somehow struggled on through the post-hippy years to become an annual event, and then a national institution. Bedraggled students in expensive Afghan coats, smoking expensive Afghan dope, slowly became the British Establishment, had trend-following children, got lazy and ended up paying £238 to attend, dressed in Festival Chic and arriving in their BMWs, for a few days of variety turns cutting edge art. Needless to say many modern attenders would have scorned to slum it in the conditions of the seventies – it’s now a cultural event shown live on mainstream TV, rather than a protest against the Monkees and suits.

Statistically, thousands of this year’s punters voted Conservative the week before. But somehow, at a Rock festival, supporting Mrs May is implausible. It was always so – when I was in a blues band in the eighties, it was easy to be invited to play at events to support the Miners’ Strike. But rock benefit events for persecuted Chinese Christians, or against Baader-Meinhof terrorism, were never going to happen anywhere. Neither would they now – any more than a Conservative Prime Minister would be given equal stage-time with Jeremy Corbyn at Glastonbury, unless it was to throw brickbats at her. And yet, strangely, the Conservatives had won the election, more or less.

The implausibility of any other political viewpoint than the left-leaning is also true throughout academia, and therefore in the professions dependant on it for graduates. I speak here of the “moderate” UK, which ostensibly has lacked the left-right political and religious polarisation seen in the USA.

In philosophy, the excellent Roger Scruton’s academic career more or less ended decades ago when he critiqued intellectual Marxism (and more recently, left-wing European Postmodernist poseurs). In history Victoria Bates blogs on the situation she finds at Bristol University. In journalism Peter Hitchens is the man they love to hate even as a writer for the paper-they-love-to-hate (with some credible reasons), the Daily Mail. His late brother Christopher, far more rabidly left than Peter is right, somehow contrived to be treated as a mainstream, loveable rogue.

Sociology was an entrenched Marxist discipline even when I did social psychology at University (Reich and Marcuse were required reading, gratuitous anti-religious comments were routine in lectures, and history was in all seriousness divided by one lecturer into pre- and post-Woodstock). The one Christian who taught me (on Piaget) had entered the field when instigating student riots in ’68 – his conversion left him in a profession it would have been hard, or impossible, for him to enter as Charismatic believer.

Even the church follows contemporary plausibility structures. Once the Church of England was said to be “the Conservative party at prayer” (whilst Methodists all voted Liberal). But my curate friend from Oxford told me last week that “all her clergy friends” support Jeremy Corbyn. All of them? Why would that be, when half the clergy don’t even agree on believing the Bible? This article gives some insight.

One should be very concerned when all right-thinking people agree on the correct flavour of political thought. Politics is a matter of opinion and judgement. When it isn’t, and only one political view is acceptable to those who form opinion, it’s called “totalitarianism”.

Yet this post isn’t about politics, but about why certain kinds of politics become plausible to the point that it’s difficult to own any other kind in public. One reason opinion polls on both sides of the Atlantic have been spectacularly wrong is because of internalised shame about certain political opinions – you’ll vote for them (until the option is taken from you), but won’t even admit it to yourself, let alone to a pollster.

Plausibility affects ethics too, for much the same reasons. The leader of Britain’s third party, the Liberal Democrats, an Evangelical, was so pressed on his views about same-sex marriage during the election that he has had to stand down. Ostensibly press (and social media) harrassment was a distraction from his policies, as he would never wish to impose his religious views on others, he said.

Spontaneous protest against the recent tragic fire – posters and cheerleaders supplied by “Movement for Justice”, a Trotskyist group.

In practice, it demonstrated that traditional views on marriage, held universally and from time immemorial round the world until a few years ago, may no longer be even held privately in the mainstream political arena – let alone be publicly represented at the ballot-box – thus effectively disenfranchising traditional Christians both Catholic and Protestant. Remember that hardly any British denominations have, so far, supported same-sex marriage: but political silencing is already making that stance even less plausible, which is of course the aim of the strategy – I learned from the New Left at university (not least from my reformed Piaget tutor) that manipulating power was far more important to them than seeking truth, even when they were talking about power as oppression .

All this political discussion was really working up to a subject closer to our usual fare: the active involvement of God in natural events. Historically speaking, this virtually defined theism, and was axiomatic to all orthodox streams of Christianity from New Testament times on until the Enlightenment (remember the Enlightenment? That was what showed that modern man cannot believe in the Virgin Birth or bodily resurrection).

Wright’s critique of Robinson describes well how this aversion to God in nature entered our “plausibility structures”:

[The Enlightenment Revolution cut] God loose from the world, drawing on the old upstairs/downstairs world of English deism. Religion became the thing that people did with their solitude, a private, inner activity, a secret way of gaining access to the divine rather than either an invocation of the God within nature or a celebration of the kingdom coming on earth as in heaven. God became an absentee landlord who allowed the tenants pretty much free rein to explore and run the house the way they wanted, provided they checked in with him from time to time to pay the rent (in much middle Anglican worship until the last generation, taking up the collection has been the most overtly sacramental act) and reinforce some basic ground rules (the Ten Commandments, prominently displayed on church walls, and the expectation that bishops and clergy will ‘give a moral lead’ to society). As we know, the absentee landlord quite quickly became an absentee…

Nowadays, despite the demise of Modernism, it’s hard to admit in polite company a belief that God controls nature. One may demonstrate it clearly from Scripture or Church History, and watch people’s eyes glaze over. Amongst theistic evolutionists, that’s closely tied to the metaphysics-lite Enlightenment view of science, which divides the world into natural causes independent of God and (maybe, or maybe not) supernatural miracles which usually happen only in the Flannelgraph-Bible world. It’s a massive error, based on a false (and intellectually discredited) metaphysics, and it turns the God who reveals himself through every single event in the world into the God who hides himself so well that he leaves no gaps in “natural causes” to hide in.

Nowadays, despite the demise of Modernism, it’s hard to admit in polite company a belief that God controls nature. One may demonstrate it clearly from Scripture or Church History, and watch people’s eyes glaze over. Amongst theistic evolutionists, that’s closely tied to the metaphysics-lite Enlightenment view of science, which divides the world into natural causes independent of God and (maybe, or maybe not) supernatural miracles which usually happen only in the Flannelgraph-Bible world. It’s a massive error, based on a false (and intellectually discredited) metaphysics, and it turns the God who reveals himself through every single event in the world into the God who hides himself so well that he leaves no gaps in “natural causes” to hide in.

Critic Wayne Rossiter may not be far wrong in dividing most TEs into three classes:

(1) Some massively compromise Christian theology, so that it might fit snugly round evolution, (2) Others create artifical firewalls between their scientific and theological beliefs, so that they cannot harm one another, (3) Still others hide God in the distant and undetectable cosmic background, and claim that he is somehow pulling the puppet strings on every subatomic particle in the universe (and that things only look random).

To a depressingly high proportion, “design” is a dirty word, together with the slightest suggestion that any particular feature of nature demonstrates God’s power and wisdom, because these are excluded, somehow, by the existence of “natural causes”. It never seems to occur to people that “natural causes” are entirely a culturally-conditioned human construct – and being internally incoherent (for how can they exist or operate apart from God’s will?), actually low in credibility. The real reason there are no gaps for a God of the Gaps to fill is because God is all in all, not because he has hidden or absented himself.

But in truth alternatives to theistic evolution are often as reticent on this biblically-fundamental idea as those wedded to “soft scientism”. Intelligent Design tends, at least to some degree, to divide events in nature between design and “natural causes” (though in part this is a methodological distinction, as it may sometimes be in theistic evolution, and it’s not true of many leading ID people, who have as high a view of providence as a small minority of TEs). And the same is true of Creationists, who willy-nilly find themselves caught in the current plausibility-structures that neglect God’s ongoing activity in nature, even as they stress it in the initial creation, largely because they have imbibed the idea that nature itself is fallen, and that God’s involvement would therefore be tantamount to commissioning evil.

The point to make is that, given Christian faith, there is much in Bible and historical doctrine that resoundingly affirms God’s ongoing control of nature, and nothing in science, apart from some customarily associated metaphysical assumptions, that can deny it. To the Christian it ought to be perfectly credible – but to the human product of modern society and a modern education, it remains implausible.

Just as the Virgin Birth and the Resurrection were to ‘man come of age’ back in 1963.

Thanks for these discussions … this and the Lisbon followup in your next post about our cultural reactions around notions of God’s judgment or distance.

Reacting to Rossiter’s critical categorization of TEs:

(1) Some massively compromise Christian theology, so that it might fit snugly round evolution, (2) Others create artificial firewalls between their scientific and theological beliefs, so that they cannot harm one another, (3) Still others hide God in the distant and undetectable cosmic background, and claim that he is somehow pulling the puppet strings on every subatomic particle in the universe (and that things only look random).

I find it only natural to determine where I or others from within that targeted criticism would place ourselves among his choices. Somewhere among or between 2 or 3 I suppose though neither does much to capture other more likely possibilities. I can understand how I personally could (and I believe have!) stood accused of being squarely in #2. The problem, though, is that he assumes “the firewall” is entirely of my/our own creation and maintenance. From where I’m standing, walls can be discovered as well. One can encounter walls of human contrivance as they explore about, but one can also encounter natural terrain barriers that not only existed before our encounter but will stubbornly persist whether we believe in them or “maintain” them or no. There simply are some things that science cannot contain within its analysis, and it has nothing to do with us trying to throw up hasty “no-trespassing” signs against would-be scientific explorers, but has everything to do with us (perhaps even as enthusiastic explorers ourselves) encountering realities that just defy the principles of access to our accepted empirical methodologies.

Your notes on our reactions about God’s judgment and plausibility vs. the long-surviving issues of credibility are clarifying and challenging at the same time. We evangelicals here in the U.S. have knee-jerk reactions to distance ourselves from (and heap opprobrium on) right-wing evangelists here who retrospectively explain flood or hurricane disasters as being judgment against specific cities, usually for harbored or celebrated sins on the top-ten naughty list of the accusing evangelist. I can imagine just such a reaction also against Amos or Obadiah in their days too. But as I recall the prophets themselves weren’t always unchallenged. Without looking it up, I suspect more than one passage has something to the effect … “so you think Sodom or Gomorah were bad do you? … now let me hold up a mirror for you and explain what you are looking at just to make sure you get the point …”

This sensitivity to and reaction against hypocrisy is enlisted by many I think in a healthy way, but also beyond that by others as a stepping stone toward dismissal that any judgment could be happening at all. You challenge me to be careful about such appraisals. Maybe its best just to not make them, but listen thoughtfully, critically, and prayerfully to others when they do.

…continuing thoughts about prophetic judgment …

Perhaps when judgments have been uttered, we could divide populations into three rough categories: 1. individual(s) delivering the judgment; 2. recipients (prophet’s intended audience) for that judgment; 3. watching bystanders –either contemporary to, or perhaps interested parties reading of it from a later epoch.

Many of us like to imagine we are commissioned by God to join the #1 group. Some really are. Many are not. There can be little doubt on that I think. Nobody likes to find themselves in the #2 group. But such person(s) are usually are not in a position to be cultivating any haughty attitudes, though they might feel the heat of rising self-righteous anger (whether appropriately or not) as they nurse their wounds or scrape some broken potsherd across their itching boils. But most of us have the “luxury” (as here right now) of being in group #3. That might be the most dangerous group to be in as it tends to provoke prophetic ire in the Bible when we read of God’s reaction to the attitude characterized by: “well, at least we aren’t as bad as they were!” But there does seem to be some precedent for a proper role for group #3 too … something more in line with Jesus’ discussion in Luke 13 about the tower of Siloam that had fallen. He seemed to be advocating that the proper group #3 attitude in that case would be a sober self-reflection that we are no better than they were.

Hi Merv

Your two main discussions are on very different lines, but maybe I should try to integrate them.

Dead right. I managed to do both those posts without mentioning the Siloam tower, about which we know nothing except through Jesus’s words in the gospel. But it seems directly comparable to the Grenfell Tower fire, in that it was a local catastrophe, and no doubt there were both fortuitous and humanly avoidable causes at Siloam too, though a lesser death toll than Grenfell.

Jesus’s words are, as you say, intended to avoid the complacency of schadenfreude – “God has punished those wicked others” – not by denying that God is active in governing the world (and by implication in judgement), but by suggesting that such judgement is restrained in order to bring the sober self-reflection you discuss to the majority: “Unless you repent, you will all likewise perish…”, says the Lord.

Nowadays amongst Christians, the tendency is to say that a disaster has “natural” and/or human causes, but not divine causes. Or perhaps that biblical disasters can be from God, but that real ones have natural causes (“flannelgraph thinking”).

Thus last week, since I’d just written the blog, Lisbon came up in my Bible study on Daniel 9, which soberly prophesies a future re-run of the destruction of Jerusalem and the temple at the time of Messiah. At least one person just couldn’t make a connection, on the simple grounds that we know earthquakes fortuitously hit people living on fault lines and therefore come under “natural causes”.

Now her thinking emerges directly from “a disconnect between scientific and theological belief” (though she’s neither a scientist nor, as far as I know, has any particular origins position). The “insulation” consists of separating the “Bible World” from the “Actual World” – but of course that can’t work because the destruction of Jerusalem is in both, and the result can be seen directly at the Wailing Wall and in Middle Eastern politics.

The question is whether that disconnect is the result of a “natural fault line” between what science shows and what theology shows, or whether it indicates that science, both at popular and professional levels, has created the firewall by its philosophy and/or methodology – the thing I suggested happened through the Deists after Lisbon.

What is sure is that putting disasters out of the “theological” category and into the “natural” category fundamentally affects spiritual life, because one no longer has just grounds for penitent reflection either personally or corporately, but only for half-suppressed recrimination against God for not being more competent in designing nature. “I guess we’ll all die one day” is just not the same reflection as “I too will perish in the same way unless I repent.”

Replace “human disasters” with “biological copying errors” in the above and ones theology of creation becomes similarly altered: natural causes replace God’s purposeful activity.

You write of your friend: At least one person just couldn’t make a connection, on the simple grounds that we know earthquakes fortuitously hit people living on fault lines and therefore come under “natural causes”.

Allow me to join your connectionless friend in engaging this just a bit more. Yes, I know that identifying some proximate cause in no way overrides or replaces prophetic narrative about the same event. Yet surely there must be something said about the proximate cause. Let’s take the non-hypothetical situation of motorcyclists and helmets. So it is known that those choosing not to wear helmets die at a far higher rate than those who do. Should some prophet declare God’s judgement on cyclists, and we knew somehow that the Judgment was authentic, would we so easily dodge that judgment then by donning the required head gear? Or knowing what we know now about earthquakes, are those who are both terrified of earthquakes and also wealthy enough to do something about it in the privileged position of moving away from such zones and therefore beyond the reach of that particular judgment? I know –earthquakes aren’t the only natural disaster. But still, those who don’t like the thought of tornadoes probably won’t choose the high planes. Those avoiding floods avoid the lowlands. Those avoiding earthquakes and volancoes … So it would seem then that God’s judgment is inexorably more harsh against the poor who cannot just pick up and move from whatever circumstances they were unfortunate enough to be born in the midst of. Can that be right?

To pile on that a bit more; how do we know the prophet isn’t merely following in the spirit of one of Job’s friends? There seems to be much biblical occasion to call that into question.

One final admission of struggle with our tower of Siloam passage. Of what use is it for Jesus to warn that the rest of us too will perish if unrepentant when we (and likely they too) all know good and well we will perish anyway? Was he speaking of another (spiritual) kind of death? In which case, his words would seem a harsh indictment of the 18 unfortunates under the tower. I get it that we are all no better than those who suffer judgment, but knowing we will all perish anyway kind of guts the threat does it not? Sort of like knowing ahead of time that a terrorist plans to kill all the hostages anyway regardless of whether you meet the given demands.

Okay — just one more. Before we go all off on judgment, Jesus still doesn’t let us rest there either. The man born blind –Jesus emphatically rejects the disciples’ conviction that this must have been judgment for something (either the man himself or his parents –somebody sinned, right?) and He declares instead that it was rather so that God’s glory could be shown. Add that in with Job and we see that our Judgment enthusiasms here have some serious problems.

What are the answers to all this, Jon? Life, the Universe, and Everything! In twenty words or less, please. [just kidding — I think I’m now channeling a certain George from another site.]

I’m only just now catching up on news of the Grenfell Tower fire you mentioned.

I’m so sorry. Such flippancy around the discussion as what I exhibit I would take back with that tragedy so recent. I know time doesn’t undo the loss, but somehow it seems inappropriate to speak of it so soon.

Merv

Your flippancy is more serious than a lot of the self-serving political reaction to the Grenfell tragedy, so I don’t think you need feel too guilty about it.

N T Wright points out that in the Siloam case (in the same passage as “Pilate mixing worshippers’ blood with their sacrifices”) Jesus was speaking very literally – in 70AD many perished exactly likewise – by the collapse of the city and the slaughter in the final sanctuary, the temple. So he’s talking about temporal, not final judgement, and that in relation to his own ministry. But that doesn’t alter the case that God habitually acts in the world in that way: “Does disaster come to a city, unless the LORD has done it?” (Amos 3.6)

I think the question of prophecy is, to some extent, a distraction to the question of divine government, except insofar as those biblical examples establish the theology. Nobody (as far as I know) prophesied the Great Fire of London , but the default position of the people was that there are no causes independent of God, despite the (soon known) cause of a bakers fire in Pudding Lane (though they lynched a couple of Catholics first, I believe). It took only six lives, but much wealth: in that case, the poor had less to lose.

As you say, we are all going to die, and in strict terms justly, and Jesus himself demonstrated that the godly innocent, as well as the “ordinary folk” may die along with, or even ahead of, the guilty – another thing stressed in the latter chapters of Daniel.

But I don’t think that equates to God’s picking on the poor who inhabit earthquake zones and so on – out your way the videos seem to show affluent cities being hit by tornadoes just as often as trailer parks. Floods may affect marginal land, but conquests target the cities, and the plunder. When Jesus foretold the Fall of Jersualem, the ricjh had the opportunity to heed the warnings and escape, even if they didn’t repent. But it was the Church that heeded further prohecy and escaped to Pella – the Sadducees stayed close to their wealth and perished with it: most of the others fought the Romans and each other and still perished.

And yet the mystery of how and why God acts remains. In Revelation, the “horse” of famine “must come”, with the other three, before the end. But the “oil and wine” are spared, which seems to confirm the realistic finding that in times of famine journalists, dictators and so on manage to find decent food whilst the poor starve. Why? We’re only told “Shall not the Judge of all the earth do right?”, and that in connection with the toytal destrcution of the cities of the plain, in which not ten righteous people were found.