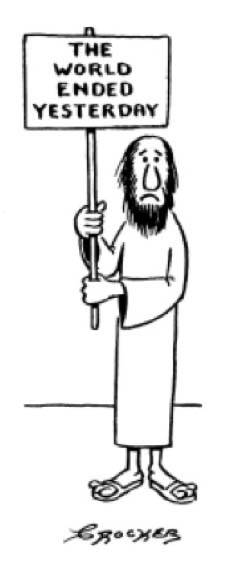

It’s very instructive, for understanding the times, to realise how before climate change became the stuff of our mass-media sandwich-boards, we were subjected to a whole sequence of apocalyptic predictions of the imminent end of the world. This ought to lead us to focus on who wants to keep prophesying doom, and why, without being too distracted by the actual claims, let alone succumbing to fear.

We must remember that none of these scares were from isolated cranks or cults, but were widely believed and affected public policy across the world. At the risk of missing some, and without explaining or debunking them here, we might include:

- 1967: Overpopulation, leading to mass famine by 1975.

- 1969: Overpopulation, leading to extinction by pollution by 1989.

- 1970: Pollution, leading to global cooling and a new ice age by 21st century (and loss of oxygen, and dried up rivers).

- 1970: Overpopulation, leading to dead oceans and US food and water rationing by 1980.

- 1974: CFCs, leading to depletion of ozone layer from CFCs and massive skin cancer increases by 1990.

- 1980: Pollution, leading to acid rain and destruction of water-life and forests.

- 1988: CO2, leading to global warming and massive droughts by 1990s.

- 1988: CO2, leading to sea level rise and Maldives gone entirely by 2018 (and loss of drinking water by 1992).

- 1989: CO2, 10 years to prevent nations drowning, dust bowls, “most conservative estimates” 1-7 deg C rise by 2019.

- 2004: CO2, leading to submerged European cities and “Siberian” British climate by 2020.

- 2008: CO2, leading to ice-free arctic by 2018.

- 2009: CO2, 8 years to save the world (Pricne Charles), 50 days (Gordon Brown).

- 2009: CO2, ice free arctic by 2014 (Al Gore).

- 2013: Methane: ice free arctic by 2015.

- 2014: CO2, 500 days to save the world (French Foreign Minister).

Well, you get the idea. It’s a good exercise to trace the history of all these, the high-level scientists and scientific bodies involved, the quality of the science, and the way that the failure of each new disaster is quietly forgotten: when did you last worry about acid rain, for example? Best not to use Wikipedia, though, which is heavily biased towards saying “global warming was predicted all along,” which you only have to have been there to know to be tosh.

2019, too, is a year when various bodies have expressed concern about illegal increased CFCs from Chinese manufacture of solar panels, but the “ozone depletion” in the antarctic is at its lowest since the scare… though overall there has been little in the way of the decreasing trend predicted to occur after 1990, despite CFCs being quickly banned across the world.

The common factor of all these prophecies, as I am not the first to point out, is the guilt of the human race for spoiling the planet by our activities, or in the case of Paul Ehrlich’s overpopulation, simply by existing (all the overpopulation predictions above are Ehrlich’s, which is why he now has so many prestigious awards and fellowships: in this business false prophecies are rewarded by international honours, rather than being punished by death as in the Old Testament).

As usual, the main point of my post is a little different from simply presenting this historical pattern for your consideration. For when I mused on it, it occurred to me that the first doomsday prediction of my lifetime was of a different, far more legitimate, character. And that was the threat of nuclear annihilation with which I grew up, from my earliest childhood memories.

Those of a similar age to me will remember the news reports of ever bigger nuclear tests, up to the Soviet Tsar Bomba of 50 megatons in 1961. The whole of popular culture, from Bob Dylan’s Talking World War III Blues to features in Mad Magazine (“Whenever I hear/ A bomb test is near/ I hurry to my Blue Shelter” – tune, My Blue Heaven) was controlled by the threat.

My particular obsession, though, was science fiction, and a standard scenario there (also seen in George Orwell’s 1984) was of a world essentially obliterated by nuclear war and struggling in the aftermath. Typical of the genre was Walter Miller’s 1959 Canticle for Leibowitz, but there were hundreds more: even in Dr Who the Daleks were conceived back in 1963 as post-nuclear mutations.

So I’m sure I’m not alone in having assumed that an all-out nuclear war would spell the end of most, or all, life on earth. Bare rock, nuclear winter, radioactive forbidden zones. Failing that, we’d be a race of mutated freaks (“The girl that I marry will have to be/ A purple-skinned beauty with two heads or three” – another one from Mad).

Still, for the nuclear scare to be the odd one out amongst a plethora of exaggerations, politicised science and propaganda seemed to me to be … untidy. After all, the Nuclear Test Ban Treaty was signed in 1963, just 4 years before Ehrlich kicked off on his eugenic revival. Coincidence, or was it necessary to replace one fear with another?

H. L. Mencken (1880-1956) wrote:

The whole aim of practical politics is to keep the populace alarmed (and hence clamorous to be led to safety) by menacing it with an endless series of hobgoblins, most of them imaginary.

Well, nuclear war having, for practical purposes, retreated into the past now, maybe we accept the old assumptions unconsciously, but I was interested to hear a video of a nuclear scientist pouring scorn on the wider risks allegedly posed by the Chernobyl disaster: nobody beyond the immediate events, he said, has died from that or any other nuclear accident, whereas a good number of elderly and sick have died from being evacuated.

Here’s a link to the first chapter of a book on Civil Defence, produced back in the “nuclear era,” but endorsed by serious nuclear scientists and clearly citing the best evidence. It rightly says that a nuclear war between the US and USSR would be one of the greatest disasters in the history of mankind, but also debunks pretty well all the doomsday hype.

Strategic warheads would actually cause relatively little harm outside blast areas, and survival is possible even within it, most radioactivity dropping quickly enough for nuclear shelters to be viable. Food supplies would not be obliterated or rendered lethal, given simple precautions. And the experience of Hiroshima and Nagasaki showed that even bombed cities would not remain uninhabitable in the long term.

Late-onset diseases occur, in fact, at close to the rate in non-exposed populations, that is to say pretty rarely.

In short, life – and even civil life – could go on much as it always has in the aftermath of the ravages of war. Even conventional war can, of course, recalibrate political and economic situtations drastically, and end civilizations. But the end of Russian or American world dominance is a very far cry from the picture of fur-clad savages reverting to the stone age.

This understanding makes sense to me, and seems closer to the science I’ve learned than the apocalyptic images I grew up with. So how did the latter get so ingrained in the public imagination? There are probably a few factors.

For a start, east and west had a policy of “Mutual Assured Destruction,” so it paid both governments to raise the stakes from the idea of “mutually assured considerable damage” that might be closer to reality. Admittedly some of the science used in my source was not available at the start of the Cold War, but much of it was. Even basic physics would rule out the worst-case scenarios.

Perhaps there was an element of Mencken’s generalisation too – that governments use fear to control their populations and keep us compliant. Did Kruschev and Kennedy really believe that the other might press the button, or were both sides also playing a political game at home?

Another factor was that public fear is seldom constrained by sober assessments. Is a CND activist going to be more persuaded by an optimistic (“blasé”) Los Alamos government-paid physicist, or by graphic Sci-Fi horror stories and press speculations? Actually, one factor is that activists in the West were being persuaded directly by Soviet agents planted in their midst throughout the nuclear disarmament campaign, for very obvious reasons: if you’re a totalitarian government and want to win the Cold War, best harness the democratic processes of your opponents.

The extent of Communist involvement is shown by the way the environmental movement grew out of the anti-nuclear movement (Greenpeace being one notable example). Greenpeace‘s left-wing politicisation took a few years, but in Germany the Green Party was conceived by Rudi Dutschke, who died before it could be launched, and by our old friend Daniel Cohn-Bendit, “Danny the Red.” Russia was, and is, a major user of nuclear power, whereas the Left in the West has always been against it, and the Environmental Movement, for reasons examined in depth in Rupert Darwall’s Green Tyranny, still is.

Even apart from external influences, though, “Noble Lie” ethics would ensure that anti-bomb campaigners would be liable to overestimate the effects of nuclear war to garner maximum public support, even if they were aware of the true limits of its destruction. And that would include activists who also happened to be scientists, one such quoted in my source being Carl Sagan.

I can vouche that many CND supporters were not so clued up: I remember talking till 4.00 am with a couple of nuclear activists for whom I was baby-sitting in the 1980s, under a Christmas tree festooned with CND badges rather than chocolates or glass balls – I kid you not. They fully expected the world to end soon, and had only last vestiges of hope that governments might see sense. Sadly they split up soon thereafter, but the world is still here.

A final factor is the role of the popular writer: true Sci-Fi apart, the imaginative appeal of a novel like Nevil Shute’s On the Beach has a greater influence on public ideas than some dry science-citing manual of civil defence. After all, any school-child remembers Al Gore’s movie, but how many adults have ever bothered to check out raw climate data? And remember how the UK government’s effort, Protect and Survive, was scorned on principle, as the world knew survival was impossible.

Mind you some of the offical advice was laughable – an earlier version gave tips like, “Be sure to switch off the gas, or there may be an explosion,” amd “If you’re caught out in the open, duck behind a tree.”

And so it’s possible in our times – when everybody is expecting the weather to kill the world and nobody much is geared up for a nuclear holocaust – to see that even that first scare, no doubt contributing to insecurity and angst amongst many of my generation, was grossly exaggerated. And it is also possible to think of a number of reasons why that was so, and why our concept of nuclear conflict owes more to science-fiction than to science.

Unless there should be an escalation of problems involving Iran or North Korea, Dr Strangelove is old hat. I think it’s instructive, though, to apply its lessons to today’s fears of a man-made end. You may see some similarities.

The really sad thing is that, currently re-reading Nick Davies’s Flat Earth News I find that he dealt fully with the myth of radiation dangers in that book, via his investigation of the contradictory claims about the deaths following the Chernobyl disaster.

I read that book only 10 years ago, but since then had completely forgotten what it said about the science of radiation, having unconsciously soaked up the “ambient noise” in the media about its terrible dangers.

And so it seems that one of the biggest dangers in swimming against the tide is simply forgetting you were trying to do so.