That slogan, together with “Stay Home,” has been dropped from England’s political messaging, but it’s an interesting one to focus on a little in the ongoing SARS-CoV-2 saga.

Those whose memories have not been reprogrammed by the current version of history will remember that, before lockdown, British policy was to encourage herd immunity, the only strategy that uses known technology (the human immune system) to make the inevitable survival of the virus unproblematic.

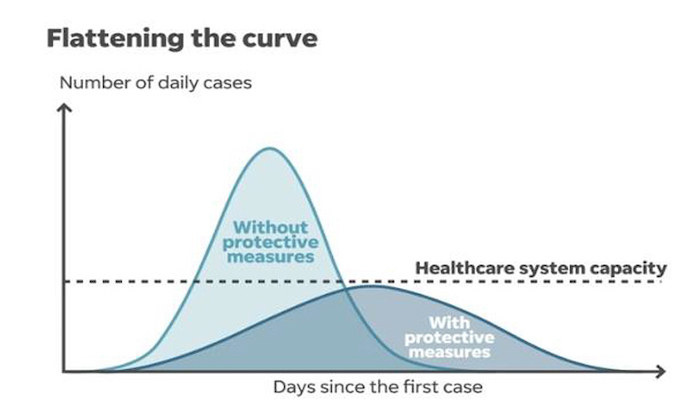

Fazed by Imperial College’s apocalyptic modelling, however, Boris Johnson became afraid that 500,000 people could die (an implausibility he repeated for effect even in his TV address last weekend), and lockdown was introduced, as in every other country joining in the Groupthink, in order to “save the NHS.” The logic of this was very clearly stated by the scientists at briefings: by slowing the spread, and “flattening the curve,” NHS intensive care facilities could have time to increase their capacity and not be overwhelmed, resulting in treatable COVID patients dying unnecessarily.

This made some sense, but it’s good to remember that ITUs would not actually have been overwhelmed – it’s just that the patients could not be admitted to them, and would be dying at home, or in hospital corridors, as happened initially in Italy. Still not a pleasant situation, but once the situation quietened down, the NHS would get back to normality as it has in many previous years when influenza epidemics overloaded its capacity. Government would, as it has for many decades, spend some more money for next time, and claw it back when the nation’s books didn’t balance.

Incidentally, Boris Johnson referred in Parliament to COVID-19 as “a once a century event,” which is tosh as so far the deaths have not even reached those from flu two years ago, let alone the 80,000 of 1968-9 and other outbreaks. But if he believes it, then a good place to save money in future years would be in pandemic planning, being a problem only for four generations ahead.

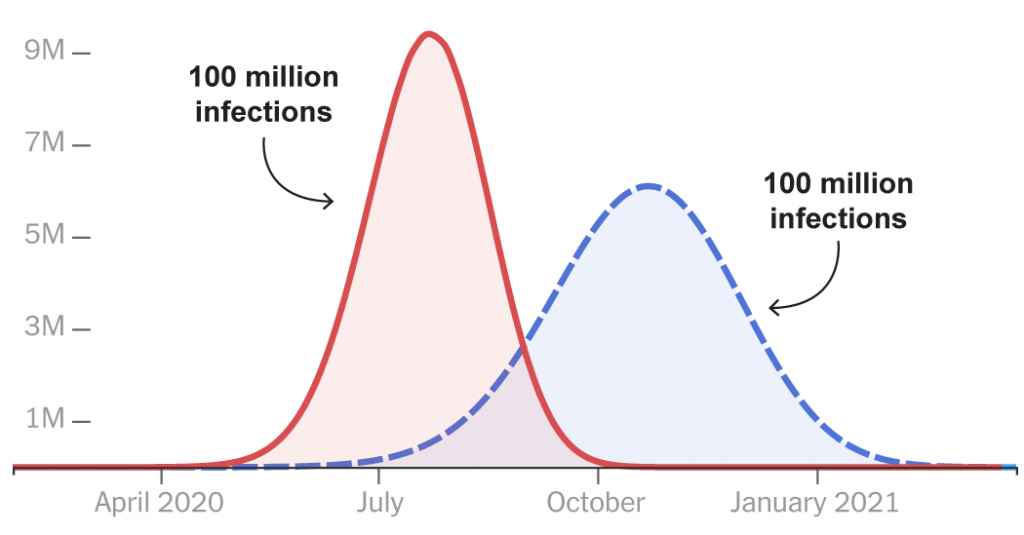

In the (worldwide) event, either lockdown was implausibly effective, or the models grossly exaggerated the need, so that expensive new emergency “Nightingale Hospitals” stand largely unused, awaiting the bogeyman of a second (or third) phase that, for some reason, would be much worse than the first.

The actual implication of “flattening the curve” is clearer in the graphic I flashed briefly on my Imperfection video, thereby probably letting most people miss the irony:

The point is that the area under the curves is identical: not a single case is prevented, and not a single life is saved, apart from the small number of severe cases surplus to capacity who could have survived through intensive care.

But as in Iraq, Afghanistan and all the other recent wars in which we’ve got involved, mission creep has firmly set in: somehow lockdown got to be about “saving lives,” and now that the ITU capacity is surplus to any likely requirements, the NHS message has been dropped. Of course, that commits us to an exit strategy based on wishful thinking about a universally effective, safe, and universally available vaccine becoming available whilst we all live in irrational fear of each other, and submit to electronic surveillance that is unlikely now ever to be abolished (after all, contact tracing works for terrorists and dangerous dissidents too).

Did we save the NHS, though? Today, the BBC news pointed out that hospitals are currently operating at 60% capacity, GP appointment requests are down by 30%, and waiting lists for everything from hip-replacements to cancer are likely to be disrupted for months. The public is aware of this, but that disquiet doesn’t open the routine clinics and operating sessions, nor remove the fear of catching the plague or, worse still, further burdening those brave boys and women daily risking their lives in the constant battle on the wards. Who would want to be the rear-gunner in a wart clinic in Exeter?

The “disrupted for months” message ignores, of course, the fact that years of austerity had already begun an inexorable lengthening of waiting lists, overburdened GP surgeries, and overcrowded casualty units. With expenditure on COVID-19 currently equalling the cost of the NHS, and the deepest recession in memory looming, the future ability of the NHS to do what it is there to do – to treat the nation’s illnesses – is scarcely likely to improve. The NHS as an institution was never at risk – what we’ve done to it in the name of COVID-19 is to incapacitate its normal function. We’ve saved the brand, at the cost of the product.

Part of the current NHS under-performance is due to government-induced patient COVID-fear. One example familiar from my own career is the rise in deaths from myocardial infarction. We had reached the stage of public knowledge a decade ago that mere minutes make a difference in survival for this, but even so most weeks some old guy would come into a routine morning surgery having had chest pain during the night, and would show a massive infarct on ECG. I tore my hair out to get people to treat chest pain as an ambulance emergency (as opposed to dialling 999 because a chemist had found their routine cholesterol was raised!).

So there is an inbuilt human tendency to underplay ones symptoms, and a perceived overload of the health system by the Worst Disease In The World Ever only encourages that. A relative told me just today that he’s been getting a flashing light in one eye. My family is odd, in that decades of having a doctor close to hand gives them a sounding board on whether to treat a complaint seriously or not, but most people, usually, would immediately be off to the doctor with such a potential risk to their sight. Today, they’re likely to have swallowed the message that every doctor is worked off their feet under a flood of Coronavirus illness (whereas a total of 25 people have died in my whole county throughout the epidemic – that probably correlates to about 120 confirmed cases), and choose to “wait and see”… or maybe wait and lose their sight.

So, it seems to me that the message that we have now saved the NHS, and can move on as long as we’re alert, is much the same as saying that we’ve won the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. No exit strategy means no resolution whatsoever, but just a lot of expenditure in a lost cause. There is a good reason why nature gave us an immune system, rather than social distancing.