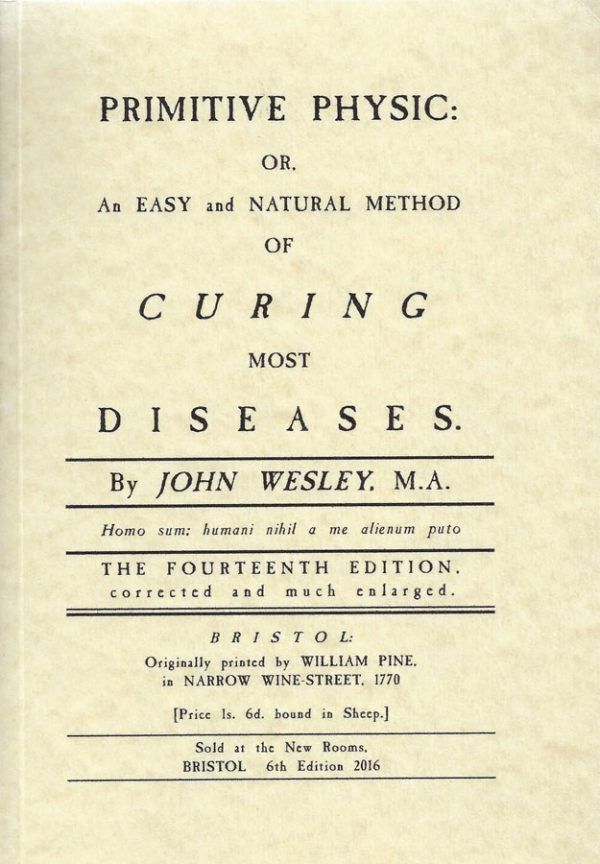

Back in the days of Richard Baxter, George Herbert or John Wesley, medical care was part of the remit of the church minister. Whilst physicians balanced the humours of the rich in cities, out in the sticks the poor could seldom afford their fees, and the pastor, as the most educated member of the community, made it his business to know some herbal cures and folk remedies. How effective they were – other than by demonstrating compassion, not to be denigrated in these days when the suffering are left to die alone – is hard to say, but then the same is true of the professional bleeders and purgers of London.

How things had changed by the beginning of my medical career! Trained GPs (for the first time trained as GPs rather than falling off the ladder of hospital specialities) were available “free at point of contact” to everybody under the NHS. And for more complex conditions, GPs referred patients to free hospital clinics which were sometimes staffed by specialist GPs, as consultants delegated their historic role.

During my GP hospital rotation I sat in on a Diabetic Clinic run by the excellent Dr Cummings, usually the junior partner in a practice run by his father. I well remember him dictating letters to GPs – yes, in those days hospital doctors communicated with colleagues in the community using real letters typed by real secretaries! “Dear Doctor X…” was punctuated from time to time by “Dear Dad…” or on one occasion, “Dear Me…”

As the years went by, the numbers of Type 2 diabetics began to multiply (as now seems apparent, largely because of the misguided dietary advice governments and doctors were handing down to the benighted people), and hospitals began to get more picky, delegating most of their care to general practice so they could juggle with the Type 1 folks’ insulin (really not as hard as it looked – I had spent three months doing it on the wards as a diabetology house-physician). GPs readily picked up the gauntlet, given the opportunities built into the system for ongoing training, and especially so as devolving patient care to primary care became government policy, and some earmarked payments became available. Most decent large practices began to set up Diabetic Clinics, as well as Asthma Clinics, Hypertension Clinics and so on. We in turn delegated the routine stuff to nurses whose specialist training we facilitated, and whom the special payments partially funded.

The government’s purpose was to save money, as hospital clinics always cost far more to run, perhaps because hospitals were increasingly manned by several tiers of management doing creative accounting and needing to be paid themselves – gone were the days of my house jobs when my large District General Hospital was managed by one ex-army major and one assistant. Pretty soon, even the former annual hospital visits were phased out, and Type 2 Diabetes became a GP-treated condition from diagnosis to death.

Not long before I retired, Gordon Brown and the civil servants negotiating a new GP contract refused to believe the medical negotiators when they said most GPs were already doing all these clinics and other management that had been steadily offloaded from hospitals over the years. As far as Brown was concerned, GPs spent most of their time on the golf-course whilst the NHS was in crisis (the NHS meaning, of course, the hospital system that been steadily cut back for “efficiency” and which had broken down spectacularly in the last bad flu season).

So, despite quite specific warnings, of which the profession was advised at the time, Brown instituted a raft of financial sweeteners to tempt GPs to do what, in fact, they were doing already. And that’s how I had a huge pay rise in my last couple of years, though it would have been far better for practice development had governments not consistently cut the recommendations of the Independent Pay Review body, and had they not immediately started a slagging-off press disinformation campaign once they realised they had goofed.

Meanwhile, a whole combination of centrally-orchestrated initiatives was making GP life increasingly stressful. Apart from the steady increase in genuine workload, politicians insisted on such things as schemes for the right to entirely useless annual checks on the worried well, or on telephone services manned by amateurs using algorithms, actually promoted as a way of getting routine advice for longstanding issues in the middle of the night. The latter led, inevitably, to a massive increase in re-referrals to on-call GPs and unbooked appointments, undoing decades of work by practices in training their patients in realistic risk-assessment. Let me tell you it is no fun being phoned at 3am because NHS Direct told your patient that her wart might be cancer and so was an emergency.

My colleagues have kept me informed about the continued deterioration since I retired. Established practices have closed, placing impossible pressures on those that remain. As GP principals have retired, practices have had to sell out to commercial companies, or NHS trusts, employing whatever doctors they can find and interested, of course, in the bottom line and the glossy brochures extolling the brand. This has also meant that the independence of the private-contractor GP has been buried under an NHS logo that now represents a state religion. Doctors jump to whatever tune the Minister of State decrees under his chronic emergency powers, or find themselves unemployed or, worse, hauled up before the GMC for heresy.

The pressures (including an exponential rise in bureaucratic tick-boxing) were making full-time partnerships increasingly unpopular, as was the deliberate feminisation of medical training that was bound to lead to more women with family commitments working fewer hours for fewer years. The salaried GP works set hours – he or she does not often have the ethos that the time to go home is when the work is all done. For me, the addition to the mix of state propaganda telling my patients I was a lazy money-grabber was the writing on the wall that it was time to go, before going mad.

Well, now even that situation has moved on. For the last two years the NHS has become the National Covid Service, and those diabetics (remember those folks who were once regularly seen by consultants?) have been entirely on their own. For many of them it has not gone well: if diabetes is a known risk factor for poor COVID outcomes, then badly controlled diabetes compounded by inactivity and alcoholic psychological support is worse.

The NHS, now organised entirely top-down with the apparent co-operation of a British Medical Association in lockstep with it, has risen to the new challenge – by working on the repeal of the service frameworks by which GPs were required to care for diabetes and the other major chronic conditions that have been thrown under the bus by Public Health policy. This is in order that GPs, trained for so many years to identify and manage whatever medical surprises come off the street, can concentrate all their efforts on carrying through the COVID vaccination booster programme on every man, woman and child in the country, apart from those who will soon be consigned to prison, as in Austria, or concentration camps, as in Australia, or starvation, as in Greece. The job has become to poison the healthy with a jab a receptionist could give after ten minutes of training, and to ignore the sick.

The country has ordered in at least two further doses of Pfizer vaccine for all, to be given every three months or so in perpetuity on current trends, but it will take at least another 3 1/2 months, according to news reports, to complete even the current round. This clearly indicates that running vaccination clinics will be a job for life for the nation’s GPs, making complex conditions like diabetes entirely self-managed affairs. This will inevitably mean early death for the hyperglycaemic millions, unless it should prove to be that all the management provided by our specialist clinics was harmful, which even the worst cynic would hesitate to claim.

I can only see one solution. And that is that theological colleges and seminaries should henceforth ditch their courses in community-building, inclusiveness and diversity, and instead teach ministers-in-training some simple medical knowledge. It will be difficult to work out in practice because, although medical services have been so rapidly run down in Britain, the strict laws protecting the profession have not: even if there’s a two-year wait to be seen by the NHS, if I give medical advice even from my lifetime of professional experience, I’ll likely end up in the concentration camp with the Anti-vaxxers.

This dog-in-a-manger attitude is even worse amongst the Labour opposition, who would like to abolish private medicine altogether, so that it will be impossible to get treatment even if you sell your possessions to do so – a situation even the 17th century villager didn’t face. But then they hadn’t learned the central importance of equality of outcomes.

But if it could be carried off with a degree of success, such medical training for church ministers would not only provide much-needed medical advice for the bulk of British citizens denied it by the mediaeval Papacy of the NHS, much as John Wyclif’s itinerant preachers compensated for absent or ignorant priests.

It would also equip the leaders of Christ’s church to see through the unicorn shit that we have all been fed by the public health establishment over the last two years.