A good friend of mine predicted a couple of decades ago that the next big thing, in popular religion, would be asceticism. He was, I think, foreseeing a reaction against the rampant hedonism of the times. I think there is indeed an element of that reaction seeping into our culture, so he’s been proven right about the fashion trend, at least to an extent. But I think there is a real, and largely involuntary, asceticism of the truly spiritual kind that is proving to be a necessary Christian accomplishment in our times.

First, a few thoughts on the meaning of the word, which has come to mean scorning all pleasurable experience in some masochistic fashion. But “ascetic” actually derives from the Greek word for “monk,” which in turn derives from the verb ασκεω. This, according to Vine,

…signifies to form by art, to ardorn, to work up raw material with skill; hence, in general, to take pains, endeavour, exercise by training or discipline, with a view to a conscience void of offence.

It is used just once in the New Testament, when Paul, appearing before the Governor Felix, says that he “strives always to keep my conscience clear before God and man.” In other words, he means the kind of athletic discipline which, elsewhere, he describes as “beating his body” so as not to be disqualified for the prize, having coached others.

So insofar as monks “renounced the world,” the aim, at least originally, was to renounce only whatever in the world, even when God given, might detract from their aim of knowing God better. The Christian is in training to please God, and will choose sometimes to turn away even from legitimate pleasures to further that training. That, of course, is the actual point of Lent, which this year began on February 22 – not to give up chocolate or alcohol to prove your will-power, but to avoid what might distract from fellowship with the Lord.

Well, sometimes when the saints lose sight of voluntary asceticism of this type, God has a habit of enforcing reliance on him by taking away the props the world offers. And make no mistake, historically his action can be quite radical. Unlike the Postmoderns, God is not averse to respecting traditions. Quite the reverse, in that it is the faith handed down from the apostles, including of course the Bible and the sacraments, that establishes the continuity of the covenant God has made with his people in Christ.

In the Old Testament it was the same – the Passover was instituted by God to remember, and to call the people back, to their salvation from slavery to free fellowship with God. Likewise the temple worship bound the people together with each other and with their God. Hence Solomon’s temple became a sacred and long-hallowed place, where God’s “name” dwelt, in a way that St Peters in Rome or St Basil’s in Moscow only mimics. Yet when Israel lost faith in God, he had no hesitation in raising up the Babylonians to destroy the temple, and indeed the nation, so that those who possessed any true faith at all only had God himself to rely on.

In individual lives similar deprivations can deepen, or even awaken,faith. I know someone who is aware of being in the early stages of dementia, and has consciously to seek the help of the Lord for the things in daily life usually taken for granted. Bereavement has the same effect – and perhaps is one of the greatest challenges usually encountered in the autumn of life, which may either prepare us for glory, or demonstrate by our resentment that we never had a share in it.

Well, the last three years have, I’m certain, torn away many of the props in the culture on which we relied. I don’t think I need rehearse them here for regular readers, but I doubt there are many around us dull enough to escape entirely the onset of the Great Gloom of the “Permacrisis.” I believe there are signs that the failure of the “broken reeds” on which we have leaned in the last few generations is leading many to a hunger for God – the true God. It’s a great opportunity to point people to the fact that Christ is not a bruised reed but a rock, that he may be found, and that he is a more than adequate replacement for the world we’ve all lived for, which is quickly sliding into the sea.

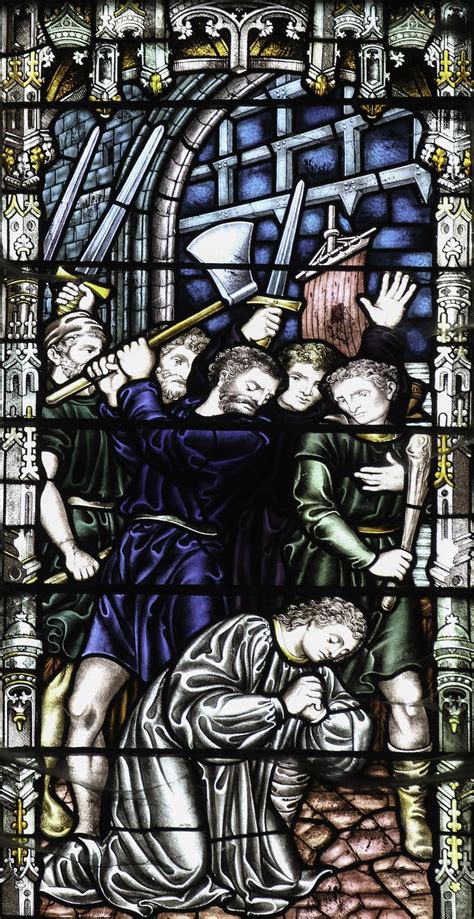

This week, in particular, many Evangelical (and other) Anglicans are grieving over the realisation that their church, as an institution, has gone badly astray from the “faith once delivered to the saints” (Jude 3). It is a grief not to be disdained. The C of E was born out of fiery spiritual struggle half a millennium ago, and despite its shortcomings and heterogenicity it has preserved both the ancient catholic tradition and a doctrinal basis firmly grounded in the Reformation. From Hugh Latimer and George Herbert to John Stott and Dick Lucas, authentic Christian living and teaching has continued within a tradition closely linked to the life of the nation by its Establishment and, of course, by the monarch’s Coronation oath. There is something special, too, about worshipping in a sanctified and beautiful space where your community has prayed for many centuries.

I was christened as an Anglican, converted through Anglicans (amongst others), married (to a confirmed Anglican) in an Anglican church, and have belonged to three Anglican congregations. I even have an Anglican archbishop (of Ulster) in my ancestry, and another archbishop (of Canterbury) was educated at my school. It is strange, at my advanced age, to enter an ancient church, or hear a peal of village bells, and think, “This institution has now officially embraced heterodoxy.”

Now many (including the global south’s bishops representing 75% of the Anglican communion) have seen that it is time to “come out of Babylon” in some way. Alternative Anglican communions are being organised through GAFCON and others. Foresighted Evangelicals (and, I assume, other conservatives like the Anglo-Catholics, to be even-handed) have been preparing for this moment since they saw the way that the LGBGTQ+ issue was being handled.

There is a certain kind of “consultation” which is made to appear as if it is aiming to establish truth, but is in fact engineered to enforce a foreordained conclusion. The issue, to the hierarchy, was never about discovering the authentic teaching of Jesus, Lord of all, on the matter, but to elevate human desire and experience over Scripture and re-brand the church as a celebration of diversity rather than “the pillar and foundation of the of truth” (1 Tim 3:15). This is plainly shown by the firm stance of nearly all the denominations on single-sex marriage before it became socially disadvantageous to take a firm stance.

But other Evangelicals, apparently less prepared, are talking about hanging in there, in the (vain) hope of influencing the direction the now deeply compromised Church of England will take. And whatever the opposite of the “Christian asceticism” described above is, I think many of these people are falling into it. The reverence for tradition must be a strong factor, together with the quite understandable reluctance to be pushed out of an institution whose leadership, rather than they themselves, has moved. Something does seem deeply wrong about relinquishing a church-owned house that has served the Christian community since mediaeval times, in favour of hiring a school hall.

I remember showing an American scholar of the Puritan theologian John Owen round the latter’s church in Coggeshall, and the vicar showing him an old pewter offertory plate from the vestry, that was used in Owen’s time. That kind of historical and spiritual continuity is not easy to come by, and I can imagine the reluctance, for the congregation and minister of a church like that, to consider giving it up. But they should remember that the Jerusalem temple, whether that of Solomon of that of Herod, had a richer heritage, yet God was more interested in “worshippers in Spirit and truth” than in holy spaces, and so “not one stone was left on another.”

The defence that the Church of England has not actually changed its official doctrines is really, it seems to me, a poor excuse for clinging to the familiar. Even the Soviets had free speech, free press and free religion written in to their constitution, but the Gulags were the reality that counted. “Handsome is as handsome does,” and there is a gospel word for saying one thing, and doing the opposite.

But other causes for ministers to “stick with it” are less ethereal and more nitty-gritty. Stipends, and even more significantly, pensions, are paid from central funds. Leave the church, and you leave your livelihood. Furthermore, many churches get far more of their funding from Church House than from their congregations. In some cases the major factor there is that half a dozen worshippers are trying to maintain a listed mediaeval building and their minister and ministries. But the central-funding model, unlike the entirely congregational funding of Non-conformists, itself disincentivises sacrificial giving on the part of even large congregations. Becoming self-supporting is, to Anglicans, a very steep learning curve indeed.

But the fear of losing time-honoured security is not restricted to the Anglicans. I belong to a Baptist Church (though I consider myself a Christian rather than a Baptist, perhaps from spending much of my life in Anglican, Congregational and Brethren fellowships). The Baptist Union is undergoing its own Downgrade Controversy v2.0, this year following the consultation exercise the Church of England had a while ago.

To me, all the appearances are that the BU leadership has a similar agenda to the Anglican bishops, and are sympathetic to gay marriage whilst hoping to hold on to the conservatives too. Otherwise, they would not have entered into an inevitably divisive exercise but held to the doctrinal lines they drew at the time that the State made it legal. But I suppose they may just be historically and sociologically naive.

It may well be, though, that the outcome is different from what the Anglicans have experienced, in that Baptist churches are fully independent, subscribing only to the broadest of principles of faith to be members. Baptists are also the most Evangelical of mainstream denominations, and over here “Evangelical” usually means a much stronger reliance on Scripture than in, say, the US. Furthermore, I am told that a conference of ministers called to oppose the proposed changes attracted far more than petitioned for them in the first place.

But even if the move were strongly outvoted and rejected, there seems no doubt that the BU will be divided. And since many Baptists have as strong a sentiment for their Union as the Anglicans do for their institution, it may well be that the fear of such a breakup will lead many to try and fudge the issue, keep everyone on board – and in the end disrupt the thing anyway for the same reasons that a majority of the world’s Anglicans, it seems, are jumping ship despite the cost. For those who remained in such a doctrinally corrupted denomination, there would always be pressure to affirm unscriptural relationships because the Baptist church in the next town does. So for Baptists, there is exactly the same need to prioritise “obeying the Lord’s teaching” over “being Baptists.”

Even though Baptist church buildings belong, usually, to their congregations (or their mortgage companies, often run by the BU!), individuals may well have to consider leaving fellowships in which they have a financial, as well as a personal, stake, if those fellowships fail to understand that this is a matter of core teachings on creation and marriage, not one of “accepting all who come.”

For ministers, the issues are nearly identical to those of their Anglican brethren: to take their churches out of the Union is to lose both their pensions and the accreditation as Baptist ministers for which they invested years of study, and treasure, not to mention the loss of friendships which, to their grief, many of those withdrawing from Canterbury’s rule have already experienced. One vicar said that the hundreds of Christmas cards he used to receive were reduced to one shelf’s worth this year. That hurts.

But we are, all of us, in the time for choosing our priorities with regard to truth and deception. Do we wear the mask and get the vaccine passport, of wear the “Live not by Lies” T-shirt? Do we dutifully wave our blue and yellow flag, or dig deeper into the actual geopolitics of the world? Do we stay in the pews our grandparents sat in, or put up with plastic chairs in a school hall smelling of veggieburgers? In other words, do we choose the comfort of conformity, or the transforming, if sometimes painful, training of the genuine Christian ascetic?