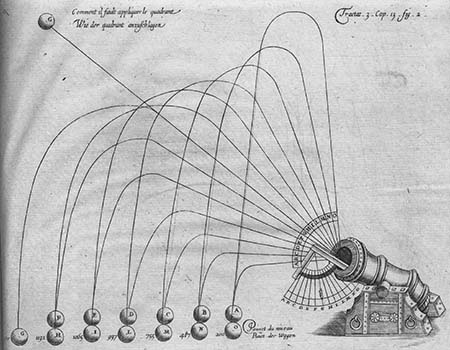

One of the astonishing examples of theory driving observation in the history of science is how Aristotle’s theory of trajectory was believed by over 2 millennia’s worth of observers – careful philosophers, archers, gunners and small boys playing catch included – until Galileo showed they were all parabolae. How could people be so blind to what every day phenomena were telling them? I’ve been wrestling with Goethe’s theory of optics – quite different from Newton’s – and have more or less decided that Newton has the edge now, but that given what was known to them, Goethe v Newton is a good example of the under-determination of theories by evidence and, conversely, that the theory you already have dictates the way you understand the evidence. Along the way, though, it’s a great example of the “Aristotle phenomenon” – how most of us can’t see what’s hiding in plain view because of the theoretical glasses we wear. Or in this case, prisms. This is the experiment Newton did that we all learned, and performed, at school, or at least saw on a Pink Floyd album sleeve:

I’ve been wrestling with Goethe’s theory of optics – quite different from Newton’s – and have more or less decided that Newton has the edge now, but that given what was known to them, Goethe v Newton is a good example of the under-determination of theories by evidence and, conversely, that the theory you already have dictates the way you understand the evidence. Along the way, though, it’s a great example of the “Aristotle phenomenon” – how most of us can’t see what’s hiding in plain view because of the theoretical glasses we wear. Or in this case, prisms. This is the experiment Newton did that we all learned, and performed, at school, or at least saw on a Pink Floyd album sleeve:

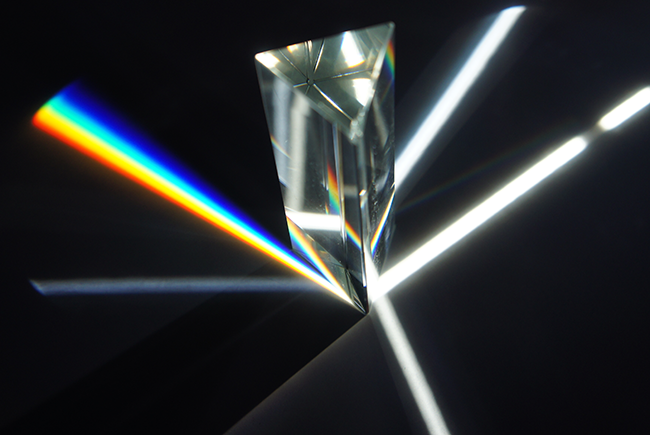

The interesting thing is that, though I must have seen a hundred such graphics preparing this column if I saw one, it’s not what happens at all, as Goethe saw when he tried to repeat Newton’s experiments. What he saw was what this photo shows:

The interesting thing is that, though I must have seen a hundred such graphics preparing this column if I saw one, it’s not what happens at all, as Goethe saw when he tried to repeat Newton’s experiments. What he saw was what this photo shows:

What’s noticeable is that the colour only begins to emerge and encroach on the edges of the white as one gets further from the prism, and Newton’s “pure” green colour only appears to arise when yellow and bright blue mix, these last two then decreasing in prominence. It’s easy to see why Goethe concluded that colour was a phenomenon arising from the interface of light and darkness, and not by differing refraction. Does the pattern not suggest two bi-coloured spectra radiating from the light-dark interfaces as the light emerges from the prism, and mixing to produce the familiar spectrum?

What’s noticeable is that the colour only begins to emerge and encroach on the edges of the white as one gets further from the prism, and Newton’s “pure” green colour only appears to arise when yellow and bright blue mix, these last two then decreasing in prominence. It’s easy to see why Goethe concluded that colour was a phenomenon arising from the interface of light and darkness, and not by differing refraction. Does the pattern not suggest two bi-coloured spectra radiating from the light-dark interfaces as the light emerges from the prism, and mixing to produce the familiar spectrum?

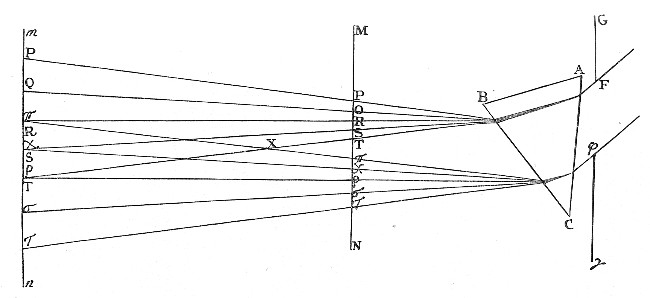

Now the first question is whether Newton noticed this phenomenon too. Goethe apparently thought not, but in fact Newton did deal with it in the second part of “Opticks”, as this figure from it shows:

![refraction_thumb[3]](http://potiphar.jongarvey.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/refraction_thumb3.jpg) Indeed, this way of representing the light is used in his own famous sketch of his “crucial” two-prism experiment, though it’s not used in most of his diagrams. A little thought makes his own explanation clear: the effect is produced by the diverging parallel beams of refracted pure colour, and the changes are from progressive subtraction from white, rather than addition to it.

Indeed, this way of representing the light is used in his own famous sketch of his “crucial” two-prism experiment, though it’s not used in most of his diagrams. A little thought makes his own explanation clear: the effect is produced by the diverging parallel beams of refracted pure colour, and the changes are from progressive subtraction from white, rather than addition to it.

Incidentally this phenomenon makes you wonder if the first of the countless illustrators of textbooks only read the first chapter of Opticks to make his erroneous representation (my first picture) and everybody else just copied rather than – dare one suggest it – doing the experiment.

But it’s worse than that. I did the experiment in school physics, and I remember the light box, the prism, and the pretty colours all being on a sheet of paper whilst I used my pencil and ruler, and later crayons, to record the result. And what did I record? Just what I’d seen in books before, that assumed Newton’s theory: nice coloured beams bending twice. And none of the other 30 in the class, nor in the years above and below, nor in schools across the country and round the world, every draw the nicely criss-crossing bands of primary and secondary colours of reality. We all draw what we think we see. I wonder what happens to the odd kid who asks the physics teacher why his experiment doesn’t look like the one in the book? Enquiring minds, I suspect, are urged to enquire no more.

Anyway, the next question is why Newton came up with his subtractive explanation rather than Goethe’s additive one, since the data of the experiment (or of any of the prism experiments) really can’t determine which theory is right, as some quite prominent scientists have conceded. Newton set great store on avoiding “hypotheses” and drawing only inevitable conclusions from experimental evidence – like BioLogos’s Melanogaster, only perhaps less confrontational. This is how he presents his research in Opticks, as a series of experiments, some deep thought, and the right conclusions. The classic way of doing science.

But it’s obvious from his early notebooks that, like Darwin, this was more rhetoric than truth. Newton claimed at the Royal Society that though the corpuscular theory of light didn’t disagree with his theory, he was indifferent to it. But in fact that theory informed all his experimental work, just as Darwin’s evolutionary convictions coloured his research despite his protestations that they followed it. Light corpuscles, varying in speed or size, would plausibly be differentially refracted by glass, but would have no logical link to Goethe’s light-dark interactions, rational though they are and consistent with so much evidence. As ever it was the idea that came first, and then the supporting observation.

Incidentally, it’s not only corpuscles that, literally, coloured Newton’s vision. Most of us see five colours in the Newtonian spectrum (and note the five spots in Newton’s sketch above). But in his circle of colours Newton names seven (orange and indigo added), making it quite clear why in the text:

…and distinguish its Circumference into seven Parts DE, EF, FG, GA, AB, BC, CD, proportional to the seven Musical Tones or Intervals of the eight Sounds, Sol, la, fa, sol, la, mi, fa, sol, contained in an eight, that is, proportional to the Number 1/9, 1/16, 1/10, 1/9, 1/16, 1/16, 1/9.

He sees seven colours because Pythagoran numerology says there ought to be seven, just as light must be refracted because Galilean (née Democritan) atomism says it’s made of particles. One last point on this: Goethe’s theory of colour, for all its faults, remains a theory of colour. Just as Galileo had already dismissed colours as a purely mental effect, so Newton’s theory dispenses with them immediately (interesting how in his diagrams they tend to appear as algebraic letters unrelated to their names), being replaced first with “angle of refrangibility”, then with theoretical invisible particles. Later, colour became a wavelength, and now it is whatever virtual and inconceivable entity quantum theory makes photons. Colour can be anything, in fact, that makes the maths work, even if completely unintelligible, apart from colour itself – which can’t be measured.

One more thing, perhaps in the “why this matters” department. One of the most obvious departures from reality of that abhorrent text-book diagram that misinforms every scientifically-educated child in the world is the refraction of light within the prism. What actually happens is more complicated, as this photo of the real experiment shows:

To orientate you, the incident light beam comes from the right, and the refracted Newtonian spectrum (not fully formed) obviously goes left. An initial reflection from the glass travels off to the bottom. But the white beam at 2 o’clock, showing little or no divergence, comes from internal reflection at the point where the emergent spectrum starts, and it in turn emerges with minimal refraction at the base of the prism. If you look carefully this beam is tinted red on the right and blue on the left, but there’s no real spectrum. There’s other interesting stuff going on too.

So in direct contradiction to the standard diagram, little or no differential colour refraction occurs when the light enters the prism, nor as it passes through the glass. Pretty well all of it occurs at the angled glass/air boundary. Goethe’s theory, or what little I’ve learned of it of it, doesn’t seem to explain that. But neither as far as I can see does anything I learned at school.

If the experiments are so misrepresented, how much is the resulting theory to be trusted?

Did Darwin outline a theory of common descent before the Beagle voyage. (I haven’t read much on Darwin in the way of biography, so I don’t know what the answer is. What’s the biographical basis for saying that the theory shaped the observations? On the optics, Feynman’s QED (quantum electrodynamics) is an interesting book for the mathematically challenged, like me (and short.) It’s been a long time since I read it, but it went far beyond my physics education.

pngarrison:

The evidence comes from Darwin’s notebooks, and Gertrude Himmelfarb’s venerable biography gives a good account (ch 6). Darwin started a new notebook in July 1837 and (quoting GH) “the theory of mutability informs almost the whole of this first notebook.” That’s less than a year after the Beagle returned, and there’s no real sign that he had any thought of “transformism” during that, so the genesis must be around that time. Natural selection was a later development, of course.

But on his return the mutabiloity of species was “all the rage in one form or another in the medical schools of London” (Bortoft), so he would have been aware of it, and his notebooks show he was more than simply acquainted with it – it was guiding his work. Not to forget the evolutionary views of his grandfather Erasmus, of course, which must have affected him once the subject was raised in his mind.

Bortoft also quotes from a private letter that rather belies the “see first, ask questions later” method he claimed to have followed in his autobiography: “no one could be a good observer unless that individual was an active theorizer,” and “…all observation ust be for or against some view if it is to be of any service.”

I’m curious as to why you think that the data of the prism experiment can’t decide between the explanations of Newton and Goethe. Goethe’s explanation predicts that the coloured rays would cross over more and more with increasing distance beyond the white wedge, while Newton’s predicts that the coloured rays should become more and more cleanly separated. Newton’s experiments were conducted over a distance of about 22 feet, which is much longer than the white wedge, and more than amply demolished the explanation resurrected by Goethe.

http://www.huevaluechroma.com/pics/6.26.jpg

Also, if you apply the procedure used by Newton to explain the spectrum of a wide beam to your final example, you’ll find it predicts that the beam should emerge with narrow reddish and bluish fringes that die out further from the prism, which seems to be exactly what you have observed.

David, thanks for posting – your own website looks fascinating and I will browse it at leisure: colour theory has always held some fascination for me as a doctor, a lifelong photographer and a lapsed painter. I shall look forward to reading what you have to say on colour vision, which I deliberately avoided introducing here, though I’m interested in how Newton’s experiments overlap with colour perception. Anyway, I bow to your professional knowledge on such matters.

You must understand that I dipped my foot in the basics of Goethe’s colour theory as a way of approaching his way of doing science, which in term was in pursuit of the wider themes of analytical versus intuitive knowledge that we’ve discussed here through the work of people like Michael Polanyi. It just seemed to illustrate that well, especially in relation to what happens once it’s popularised.

So the main reason I didn’t consider the effects of Goethe’s scheme further out along the refracted beam was that I didn’t think of it! It does seem obvious though, which makes me wonder why he seems, despite having no “scientific” credentials, to have been taken so seriously by mainstream physicists at the time, and given discussion-room since (see the Wikipedia entry here). It was that, rather than a full personal evaluation of the theory, that prompted my suggestion that either explanation might have occurred to Newton, had he not been primed by corpuscular theory.

I just wonder if the physical limitations of the apparatus available might have something to do with it. In both Newton’s and Goethe’s time sunlight was the brightest available source, and the experiments required a restricted aperture and focusing through fairly rudimentary lenses. Even at Newton’s 22 feet (larger than I imagined – mother must have had a big house) things must have been quite difficult to discern clearly.

I’m still not clear on the formation of the reflected and refracted secondary beam though – it appears to have remained largely parallel and as narrow as the primary beam that becomes a spectrum (as it ought, being internally reflected from that). Why not just a second spectrum?

Jon, I think the Wikipedia article is very selective about responses to Goethe’s theory. In his A History of Color (1999) Robert Crone sums up the reaction as follows: “It is not surprising that Goethe, to his vexation, got no response from the physicists of his time…. The people who listened to Goethe were philosophers, artists, and distinguished ladies with whom he spoke about his color theory in the Kurgarten. They are the same as those who in this century still remain supporters of Goethe’s color theory: philosophers like Wittgenstein, artists like Kandinsky, holistic prophets like Rudolf Steiner, and all those others for whom the exact sciences are incomprehensible and overwhelming, and therefore abhorrent.” Among later scientists, Goethe certainly did have an influence on physiologists, notably Purkinje, Muller and Hering, but this was for other aspects of his work than his theory of the origin of colours.

In Newton’s explanation of the refraction of a broad beam of light, differential refraction at the first interface causes an initial angular divergence of the spectral components, creating a narrow reddish fringe on the acute side and a narrow blue-violet fringe on the obtuse side of the beam at the second interface, where further differential refraction adds to the initial divergence. However in the reflected beam the red and blue violet fringes swap position, so that the second differential refraction tends to reverse the first one, and the rays proceed from that point roughly parallel.

David – thanks for second paragraph. Puts the thing to bed neatly… thinking about it, it makes Newton’s experimentum crucis almost redundant, at least as far as schools teaching basic physics with limited equipment are concerned.

Regarding your first I’ve had the same overall impression as Crone: Rudolph Steiner’s name keeps popping up wherever one looks researching Goethe (not to mention even further out people like Gurdjieff). Nevertheless, it’s interesting that any exact scientists (Helmholtz and Heisenberg come to mind immediately) were interested enough in the issues he raised to discuss them sympathetically.

I suspect it’s part of a wider issue than that of Goethe – I’ve been surprised in recent months how many of the great scientists, especiailly of the late nineteenth to mid twentieth centuries, were philosophically literate and keen to draw boundaries around the capabilities and range of “the exact sciences” (rather than finding them overwhelming or abhorrent, or even wrong). As for “incomprehensible” – maybe yes, in many cases, but that was because of familiarity rather than ignorance.

You’ll find it very interesting to compare the original sources with the spin attached to them in the Wikipedia article. Helmholtz said that in his 1853 lecture he was “mainly interested in defending the scientific point of view of the physicist against the accusations which had been made by the poet” (Helmholtz, Goethe’s Anticipation of Subsequent Scientific Ideas [1892]), and the quotation that in the Wikipedia article appears to offer support to Goethe’s theory actually refers to Newton’s theory, not Goethe’s.

Ah Wikipedia – you have to love it as a sociological window on who’s most bothered to push a particular subject.

David, I’ve now had time to read your section on colour vison, which is excellent – especially (given how I started this piece) your children’s page with the admonition to teach the adults properly!

Bearing in mind that you are concentrating only on colour, and that the same level of complexity applies if one is studying perception of form, movement, stereoscopy, and then on up the scale to cognitive meaning and then rational assessment, it’s an astonishingly good visual system.

It would be interesting to know how many of the same kind of high-level features have had to evolve separately in other visual creatures like cephalopods or insects, which after all have similar needs in comparable visual environments in order to survive (but that’s outside your department, I guess).

I glanced at your stuff on pigment-mixing too – hard to believe that the average artist nowadays would apply themselves to the theory and get to know individual pigments so well. Maybe that’s why the i-pad is in the ascendency.

Thanks again for both your input here and the link to your site.

You’re welcome Jon, and thanks for the discussion. I should have a go at cleaning up a few things like that on Wikipedia myself, but it may turn into a time consuming battle, and I want to finish some improvements on my own site first.

I’m afraid you’re right, insect and cephalopod vision are not my department!

Interestingly, if art forums are anything to go by, there are actually many amateur painters who are quite obsessed with the minutiae of individual pigments, even if they take little interest in other technical questions. Ultimately I think you have the same choice of understanding what you are doing, or not, with both digital and traditional painting.

Dr. Jon Garvey

Dr. Garvey, I recently had a chance to reread your article entitled “More on seeing what you believe” which was written right before 2015, the year of light, which coincided with SPIE events and Alhazens 1000 year anniversary. In looking at your post, the top illustration, which presumably describes the constellation Cygnus is not part of the article, however, it too is an illustration that has loads of significance in the realm of light.

In referring to your illustrations – there are 8 illustrations not including the galaxy banner with a 9th illustration provided by Mr. Briggs of Goethe and Newton color traces. Your work is excellent in my humble opinion. This is a challenging subject to describe in a concise and succinct manner. Please forgive my punctuation and writing style, I wasn’t a journalism major.

While I would prefer to communicate with you by direct email, hopefully, you will find this post useful to augment the body of your article and the materials describing the true visual mechanics of Newton’s famous prism experiments which took place during a pandemic that lasted from the year 1665-6 respectively. Tying this to Goethe’s color studies published some 144 years later was also something I have independently undertaken, although, up to this point the work has been unpublished. Given all that Goethe, Castell and others including Sir David Brewster have illustrated or claimed about Newton, it is unfortunate that Newton wasn’t there to defend his views at the time. Really enjoy your writing style.

So you Mr. Garvey and Isaac Newton both went to Cambridge where Newton studied centuries ago. I found your post while searching for images, then recognized the Newton sketch and located your site. Incidentally within Newton’s notes are what appear to be sketches of Alhazen’s work on the mechanics of human vision which makes me believe that Cambridge may have a copy of one of his early 10-11th century books. Alhazen was also was gifted in medicine so you share that in common.

At any rate, the story that you are telling is a great one and should be of paramount importance to a student’s understanding of how colored light behaves, except for the fact that as you pointed out, almost all the illustrations of this phenomenon are inaccurate. Misrepresented illustrations still appear in publications like the encyclopedia Britannica. So the purpose of this group of comments is to expand on what you have already created. I hope to continue this thread in the future. There are more details being left out at this point. Perhaps it’s best to keep it simple, but I am a detail kind of person.

What is critically apparent is that with the advent of sophisticated image rendering programs, images like the second one in your article can portray a fake experiment “photo” to be real. So one might ask of the viewing public, “what two or three things about this image that are not accurate”? In doing so it brings people back to the idea that they might want to do the experiment and see for themselves then they might want to rewrite this chapter in the textbooks. We all might want to go through the thousands of illustrations on line and remove them as well. Unfortunately we are not set up to do this as of yet. First and foremost we need to understand what is truly being visualized. Thankfully Mr. Garvey, you have done some of that educational work for them.

The next order of business here is to have someone look carefully at the Newton text describing his ray tracing emergent light diagram (which is the fifth image in your article) then compare this to the David Briggs provided illustrations of Goethe and Newton’s prism observations. I have done this, and, it doesn’t appear that the Briggs Newton illustration has the colored lines correctly represented. The emergent light from the upper triangle of light should read from red at the top through yellow. The emergent light from the lower triangle of emergent light should read from cyan on top through violet. Both the top triangle and bottom triangle of emergent light are different, however, here they are shown to be the same. Mr. Briggs drawing needs to be corrected and it should match what Newton wrote in his accompanying text. Otherwise Briggs work on color is quite illuminating.

My sense is that you shouldn’t take my word for it, it would be better for you and David Briggs to check this– see http://www.huevaluechroma.com/pics/6.26.jpg attached image by David Briggs.

Lastly I just want to point out that we might want to think of R,O,Y,G,B,I,V as only a pneumonic device to get the relative order of light colors correct and not a fixed in stone metric. There are more than 7 colors (some might even say an infinite amount) in a correctly described prismatic effect. Also most men’s cone functions are not sensitive enough to see the full range of colors that approximately 50% of women can see (citation to be provided later). Furthermore, if one plots a complete chart of spectral outputs on a linear color bar graph, they should be able to clearly see that there are wide gaps between some of the original 7 colors and narrow gaps between others. Green is vastly under represented cyan is not described… (that is another matter – so is the way that a target would need to be placed to capture the entire middle range of wavelengths from the emergent face of the prism) but back then Newton didn’t have a spectrometer so he did quite well for a guy with simple tools. The notion of 7 true colors is simply something that Newton had considered yet to this day some texts address this as though it were a proven fact. Its not in my opinion what do you think?

Hopefully there are a few tidbits of information here that you and David Briggs may find of use. Please do not think that I am trying to put anyone down here, its just that in order to correctly discuss this subject matter, one needs a number of visuals, photographs, and diagrams to properly illustrate what is being described, otherwise it is easy to fall into the trap of simply falling back to someone else’s photo rendered faux illustration. Please don’t hesitate to correct anything that I have written. Theres more to this story. Thank you for developing the content. Best Mr. Z

Hi Mr Z. Welcome to The Hump.

I’m flattered that you picked up on this piece, and it’s interesting what a rich subject it remains, even after the learned David Briggs and I had our back and forth!

My contact with David was entirely through this thread – and he got to it, I believe, through tracing my pirating of his graphic. So I have no contact details for him: you may wish to alert him if this thread continues.

That’s a very good reason for keeping our discussion public, I think, though I’ve nothing against private correspondence: you, after all, stumbled across it in the public domain!

You’ll also realise that I wrote the thing as a rank amateur, vaguely recalling A-level physics as a retired doctor interested in perception! I can’t even remember where I sourced my external material, though I’m surprised how well it stacks up on re-reading after all this time. So to reply…

First, a note about the blog header – nothing so scientific as Cygnus. I superimposed a mosaic from Ravenna on a panorama the Milky Way to symbolise a Christocentric universe… and now for the first time I see that the cross of Cygnus is, quite providentially, over there to the right. If I’d known, I might have adjusted the graphic. Now I will never unsee it. Thanks for being so observant.

Your correlation of Newton’s diagram with the text is interesting, not least because it raises the question of why the two projections are so different. I suppose one explanation could be that the images appear at different distances from the source, but that seems a little unconvincing. In any case, I agree that the diagram David linked to has missed that nuance, so if he appears here he might have a view on why it happens.

On the 7 colours (I think you meant to type “mnemonic?) I offer Newton’s desire for Pythagorean harmony in the OP. He records six only in his experiment, although as you rightly say, as a spectrum of wavelengths it ought to be infinitely gradated given a truly white source.

The clue, I’m sure, is in colour vision, about which I did a piece here. Briggs also, of course, covers it extensively on his website. What we actually see, physiologically, is the mysterious mental perception of red, green and blue, according to the sensitive frequencies of our three types of cone, and the perceptions triggered by mixtures of those when two types of receptor are triggered, ie magenta, yellow and cyan (the so-called secondary colours).

Hence we’re seeing, in a continuous spectrum, six definite colours and the gradations between them, not because of the nature of light, but because of the nature of eyes and minds. That sets me wondering why the millions of intermediate colours aren’t more obvious – what we usually see are those six and a vague merge area between.

My guess is that the frequency range to trigger perceptions of specific colours like orange or carmethine or viridian must be very narrow (giving a very fine-tuned balance of receptor response), whereas a wider band of frequencies would set both receptors humming for magenta, yellow and cyan perceptions.

Violet, of course, is seen dimly as an artifact of extreme blue with a low-grade triggering of the second peak of the red receptor, and magenta more or less disappears at the distance frequencies sort themselves out, because bright red no longer overlaps with bright blue.

That seems to account largely for the phenomena of a spectrum physiologically – the perception of colour in the real world is much stranger both neurologically and philosphically (as I attempt to explore here, to link these themes together.

If Newton sorted out his work during a pandemic, maybe yours is to get the textbooks corrected during this one, though I fear societal inertia is against you! As for me, I’m living in despair at the anti-science approach to COVID-19 of government, press, most of the public and many organs of science, including, sadly, Newton’s own Royal Society, now apparently well encumbered by geopolitics and Groupthink. It’s cold outside the box, but pretty liberating.

Dr Garvey, Your comments about how prismatic dispersion patterns may appear different relative to their distance from the source is true in regard to describing the appearance of emergent prismatic light. And, based on where the white reflective target is placed at the emergent end, the rainbow of colors may have in it a range of green hues or no green at all. If one looks at Newtons drawing you published, the line M,N is cut where the emergent light would not include the color green.

I did have a chance to look at David Briggs own work on color theory which looks to be well thought out and indexed. I sent him an email as well. Quite a complex subject in and of itself. That looks like many many years of work for him to perfect, and, quite an interesting course for those interested in color theory.

I also went back and checked Newton’s work in Optics to verify how he annotated his line drawing provided in your article and, again, for the record you have done a great job of fact checking. The reference source for this is in “Newton Opticks or, a Treatise of the Reflections, Refractions, Inflections, and Colours of Light” pp 162- 164 PROP. VIII. PROB. III. 1730 EDITION I believe Goethe, and Sir David Brewster might benefit from looking at that problem again. Also Castel the Jesuit mathematician had a few things to say about colored light. Each of these three minds from the 18th and 19th centuries has a published drawing on what they assert is taking place here. That said, to this day this phenomenon appears to be somewhat controversial.

If possible I would like to communicate by email is this is available. Thanks again Best Mr. Z

Hello Dr. Jon Garvey, following up on Goethe… I think it’s very possible that he may have benefitted from the published work of Lewis Bertrand Castel, the Jesuit priest and mathematician that published a work and two illustrations on this subject in the 18th century. The first of Castels illustrations like Goethes assertion about Newton mischaracterizes Newton’s findings which were published and referenced in the above response to you.

The second Castel illustration (one of 2 in a 400 page book on color huh.. a book on color with almost no illustrations) appears to correctly describe what Goethe noted some 70 years later. Also note that Castels own diagram #2 is similar to Newtons problem described in the above response.

Just a few minor points you might want to ponder.

Also of note are Castels and Newtons interest in a relationship between light and sound. In Newtons case he used a comparison of visible colored light from violet to red as estimated to be on the order of one octave. This turns out to be very close… ie: 390nm to 780nm … how he could have estimated this is beyond me or any of the physicists I have asked. They didn’t have spectrometers back then.

Castel on the other hand created an ocular musical organ that uses colored light to correspond to the musical notes played.

So checking in with Father Castels work, or at least referencing it, might help to explain how Goethe came to publish some of his findings.

He figured it out 70 years before Goethe

Still working on fact checking… there are a few others of note that could be referenced as well…

Best to you Father Garvey Mr. Z

Perhaps the answer is less mysterious than preternatural spectroscopic insight. Newton had discovered that light, transmitted through air like sound, is like sound’s notes actually a consistent gradient, of colours.

So maybe (perhaps thinking of Pythagoras and the harmony of the spheres) he drew a philosophical conclusion rather than a scientific one. I’m not quite sure how that works with his idealised notion of seven colours rather than eight – maybe the octave would be some repeat of red in his mind.