Following on the theme of the last post, secularism, I’ve been re-reading Craig Gay’s excellent, but sadly out of print book The Way of the (Modern) world – or, Why It’s Tempting to Live As If God Doesn’t Exist. It is still available in a Kindle edition – if you can get hold of it, read it. Mine was a review copy, back in the day when I worked for a magazine and got books free. Sadly, freelancing on The Hump lacks the perks.

Being published in 1998 the book concentrates less on postmodernism than it might, but as Gay points out, the latter is only really modernism taken to a new extreme, and using a wealth of sources he exposes not only modernism’s inexorable ratchet towards excluding God, but along with that its tendency towards dehumanisation too.

I was surprised to see, on re-reading, the stress he put on my bête noire of autonomy, even citing the relevance of the Prometheus myth through a number of writers I have missed in dealing with that theme from time to time, eg here. Perhaps I unconsciously remembered his emphasis from my 1998 reading – or perhaps it’s just blindingly obvious.

The book is full of thought-provoking nuggets, like the observation of one writer back in the 1930s that automatic machines, in effect, do slave work without motivation, rest or pay. That sounds OK, in that using machines as work-units appears better than using humans in the same capacity – until one realises that, whenever there is competition for jobs between machines and people, the people will be competing with slaves, and will have to lower their sights on wages and working conditions simply to live. They will become mere “human resources”. Been in a call centre recently? Maybe not, since they’re already being replaced by bots.

Nearly a century on from that writer, AI looks like being perceived as better and cheaper even for many skilled tasks. The fact that any individual human qualities are entirely lost when machines take over, and effectively lost as humans struggle to work like machines, should give us pause for thought. Would you rather be cared for in old age by immigrant care workers on minimum wages with time only to dish out your pills and rush to the next “service-user”, or by a robot with more time but no soul?

Nearly a century on from that writer, AI looks like being perceived as better and cheaper even for many skilled tasks. The fact that any individual human qualities are entirely lost when machines take over, and effectively lost as humans struggle to work like machines, should give us pause for thought. Would you rather be cared for in old age by immigrant care workers on minimum wages with time only to dish out your pills and rush to the next “service-user”, or by a robot with more time but no soul?

One theme that occupies the author a good deal is the way that the obsessional quest for individual autonomy – which Gay, like me, traces back as far as the Renaissance, through the Reformation to the Enlightenment – has actually led to the loss of true individuals in a number of ways. For a start, insisting on the primacy of the individual self is directly, and inevitably, linked to alienation. You can only be unique to the extent you are separated from others. The quest for maximal human happiness has produced a highly dysfunctional population.

Then again, we can all see, if we choose to, how the smörgåsbord of modern life, filtered through a thoroughly superficial media, actually leads to conformity to whatever is currently in favour, and can be sold as “autonomy”. David Bowie was an icon of non-conformity, but that only makes his fans the more recognisable by their similarity. And does buying a Mac really make you different? Different from whom?

The Christian view of personhood is about the heroic, and sometimes painful, effort to build character. We see that back in the garden of Eden, when Adam failed the test of patiently waiting to learn wisdom from God. We see it par excellence in Jesus, who despite his divinity, as a maturing human had to “grow in wisdom and stature” by making the right choices in obedience to his Father. We’re even told that:

Although He was a Son, He learned obedience from what He suffered, and having been made perfect, He became the source of eternal salvation to all who obey Him…

Even the incarnate Son of God built his character by actually doing life (incidentally, that’s one reason that his life, as well as his atoning death, is vital to the Christian hope).

But secularism generally knows nothing of this, and the emphasis now is all on finding ones “true self”, which is mysteriously hidden, fully-formed, deep within us without reference to God, to enculturation or even, latterly, to biology. Currently the main focus is on sexuality as the locus of identity, but the same phenomenon is seen in less obvious form in everything from the cult of celebrity (meaning you got on TV for fifteen minutes, fulfilling Andy Warhol’s prophecy) to “bucket lists” of thrilling experiences one must have before one dies in order to satisfy (rather than to develop) that “true self”.

Without pushing the comparison too far, it’s actually much like the contrast between ancient Gnosticism and Orthodoxy: theirs not to strive to become like Christ as the apostles falsely taught, but to release the light of God already hidden within them (and only them!) through some secret key of knowledge. Religiously, “authentic faith” now no longer means true doctrine, authenticated by the apostles, but the doctrine to be found within oneself. The “true self” is the sole arbiter of what, if anything, one will commit oneself to from religious tradition.

This narcissism is increasingly even to be found in Christian worship songs, grace to grow in Christ being mistaken for God’s unconditional approval of our spiritually undeveloped, fleshly, state. “I’m loved by you, it’s who I am.” No, chum – it’s who Christ is, and who you may become by his grace, through faithful discipleship.

The idea of the independent, inborn, self flies in the face not only of Christian truth, but of science and common sense too. It’s obvious that a child only begins to develop a sense of self in interaction with others, and the nature of that interaction, together with the choices made by the child and a smattering of biological determinism, governs what kind of character that person eventually has. As far as Christian doctrine goes, that character will tend towards increasing alienation from God and man apart from grace. But the grace of Christ is a school of obedience to God’s will, which cultivates a true individual in communion with God’s Kingdom and its co-heirs.

Let me preface my last point by reference to the story in Acts, the subject of my pastor’s sermon yesterday, when Peter is miraculously released from prison. The Lord’s very special provision is clear in the narrative, as is the intense prayer activity in which it occurred.

Less obvious is that Peter’s rescue followed the execution of James, like Peter one of Jesus’s central core of apostles. Also seldom remarked upon is that the angel’s intervention led directly to the execution of the innocent guards by Herod. I don’t think the “why” of God’s selective intervention is an answerable question, but I take from it the general principle that in God’s kingdom, actions are particular, rather than in-the-mass. We cannot take the Lord’s special care for Peter as meaning lack of care for James, or for the guards – or even Peter himself, when he was eventually martyred. We, like the Jerusalem church, are called to pray and love as needs arise, and to leave the management of the world in its entirety to the Father.

This pattern is certainly true of Christian virtue, on which character (and so the whole Kingdom of God) is built. We are called to love our neighbour, as we encounter him, and not to find the most efficient way to save the whole world. The means and motives are what will, counterintuitively, change the world – not the achievement of ends.

The secularized world, in contrast, recognizing no sovereign God, must manage the whole world, rather than mere people. It tells us to save the planet, not love our neighbour. In its political form modernism seeks to quantify behaviour, and often even to monetarize it, to achieve mastery of the world. Let’s see how this process of abstraction can dehumanise us in one professional sphere, medicine, since it’s an example I’ve experienced.

A doctor operating under the traditional Christianised form of the Hippocratic ethic will be fully committed to the patient in front of him. Knowing he cannot cure the world, he will seek to cure the bit of it he encounters, and where he can’t cure, to care. He will adjust his workload according to the knowledge and strength he has, but always guided by doing the best he can for his patient, because the patient is a person made in God’s image. What that “best” is in any particular case is a moral question, in the exercise of which the doctor himself will grow as both a physician and a human being. For such a doctor, and such a patient, the obstacles in the road may turn out to be the road itself.

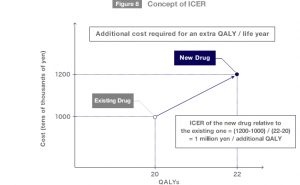

But modernism (combining secularised science, economics, politics and utilitarian ethics) replaces both a real human patient and a real human doctor with the abstraction of figures. Outcomes are measured statistically – including even the quantification of the unquantifiable in units like “QALYs” (Quality Added Life Years). In my professional career when I questioned such abstractions I was told, “We have to quantify quality of life somehow.” But that is only so once one is committed to pursuing utilitarian ethics, rather than Christian morality. Virtue cannot be reduced to variables.

After processing, all these calculations are fed back as professional performance standards to the doctor, who (unless he rebels) must then submit both himself and his patient to mathematical abtraction. Both are dehumanised in the process, because the real human issue – love – has been subordinated to an inhuman system. God’s Kingdom retreats from the gates of hell.

But it’s not only professionals who are moral humans under God. Even a slave can grow in grace and virtue by sweeping his master’s room “as for thy laws” (George Herbert) – until, that is, he’s made into a contract cleaner on a zero-hours contract by an international corporation, and rushed from job to job to maximise shareholder profits.

It’s so hard to get out of the mindset of “practical atheism”. Natural disasters show our impotence in the face of the elements – but we can neither pray nor accept the lesson of our frailty, but must find someone to blame for lack of foresight or inadequate response. The real truths about the natural world, our science asserts, are mathematical abstractions, not enchanted landscapes and marvellous fellow creatures. The real truths about all human relationships show up on the bottom line of a double-accounting spreadsheet. The real truths about communities are calculable from opinion polls.

The upside is that, whilst secularism may lose us our souls, it may also gain us the world… or what’s left of it after we’ve bent it to our corrupted wills.

Interesting post Jon – while I would empathise with your comments re machines and de-humanisation, I have often pondered on what constitutes an individual, and how we as persons may find and do goodness in this world. Christianity shows us the type of persons we should be (Christian = Christ like), yet I for one am convinced that many non-Christians may do far greater good that I am capable of doing.

The nature of human beings is at time (to me) part of the Divine mystery.

George, thanks for your thoughts.

My first reaction is the truth that we only become fully human in Christ, as he becomes formed in us, which is what Christian character is about.

But that does not exclude the existence of true virtue in those who don’t know Christ, through common grace. That goes with the traditional teaching that the image of God was marred, not effaced, by the Fall; and concomitantly, that the special relationship with God that was formed in the garden could never be completely undone. “He has put eternity in the heart of man.”

Maybe that’s support for the view that “humanity” only truly came into being in personal relationship with God in Adam, whatever cultural achievements genus Homo had achieved before that. Virtue exhibited by unbelievers would still, then, ultimately derive from encountering Christ ancestrally.

But another thought is that the very distinction I made between the virtuous doctor and the “best practice algorithm” shows that it might be possible for A to do quantitatively more good than B, and yet for that to count for little in God’s estimation if it is done from other than a Christlike heart. We are called as sinners by forgiving grace, it is true; but Christ surely also loves us for the righteousness he will bring about in us.

Good reply Jon and I agree completely. Yet I am somewhat interested in examining the robot scenario and the way our industrial/commercial culture impacts on us as a community and as persons. It seems to me that one way to see the how this is unfolding is that of, “does it do any good?” and what drives it all. Economic activity and innovation can improve life, cure diseases, feed the hungry – yet it can also oppress the poor and weak, give unimaginable wealth to greedy and vile people, and so on.

I think as Christians we may seek to avoid things that bring misfortune to all of us, but we rarely as a community, appear to change the course of the economic/industrial machine. I wonder why this may be?

George,

One factor that Gay points to is that Christianity has had trouble critiquing modernism because its roots are so much in Christianity. Much discussion of that is beyond the scope of this medium, but for example the Reformed recovery of “vocation” (that all callings, not just the “religious”, are sanctified in Christ) very easily became, amongst the later Puritans, a reason to sanctify commerce for its own sake, thence leading to the duty to make a profit becoming an absolute.

One could point to a similar thing in science – the early modern idea of harnessing nature for human good was, from early on, easily transformed into the idea that the earth is ours to use as we please, that aquiring knowledge is an end in itself rather than a way of serving God, and so on. Likewise the Protestant (over-)disenchantment of nature leads directly to materialism once God is doubted – with Christians themselves having emptied nature of meanings, spiritual beings or divine immanence.

Also, as in all ages, Christians inevitably imbibe their society’s worldview (we criticise early Christians for not dealing with slavery, whilst being pretty blind to our own consumerism). But I guess it’s compounded when one loses the imperative that the gospel ought to critique whatever society we’re in. Nowadays that’s often been replaced with the imperative to be relevant to society – for example, working out ways to teach truth in soundbytes to people whose attention span is shortened by Twitter (etc) rather, than the harder job of critiquing soundbytes and short attention spans in themselves.

Plus, of course, the fact that “There will be terrible times in the last days”!

We are now entering into the area of how Christianity has been practiced as an institution and previously an organ of the State, and within this context, the impact of personal attributes that we often discuss as virtue and vice.

I think Alan is making a valid point regarding virtue – there is (in a general sense) a natural tendency to both virtue and vice, and Aristotle seemed to equate these in his ethics, with acts that impact on individuals and their community. From memory, he used courage to show it is virtue when a person risks his life to protect and save others, yet it may bring him harm (good to others, bad to self). Conversely we can argue on cowardice.

I think the Christian faith would take an individual away from this complex good/evil, and instead show how a self may seek goodness within self, and yet also strive to do good to others. This makes repentance and growth in Christ central.

I cannot see a similar thing for a community, since a community is bound to contain non-repentant chaps. But I think a community would also contain some with an inclination to natural virtues, and others with an inclination to vices. Makes everything, including the results of robotics and computerisation, so complicated.

Hello Jon. A very interesting piece.

You suggest that virtue cannot be reduced to variables. I think this is worth pursuing!

It strikes me that virtue, much like happiness, is merely a position on an axis. That virtuous position might have been settled upon as a result of any number of factors subsumed under either nature, nurture or both but that is not important here. What is important is that every person you know will be more or less virtuous than every other person you know and that their virtuosity will be determined by a range of variables, not least your own moral position for a given situation.

For example, ceteris paribus, a homeless man asks three people in the street for help. One refuses to acknowledge the man, the second gives him £20 and the third invites the man to live in his spare bedroom until he is back on his feet. An ugly example, I grant you, but which person is the more virtuous? Are we not regarding all three as falling somewhere on that axis by reference to the good they have done? If we cannot identify and assess the variables then what tools are left to us to identify virtue?

The recent Happiness Index (yes, please can everyone now unclench their toes!) is an attempt to establish mean levels of happiness by country. Happiness is arguably as difficult to nail down as virtue so, for want of a better method, the survey used…variables!

You also raise an interesting point in your response to GD about whether ‘good acts’ (however we might define those) depend on their goodness for divine approval on the basis that the subject acts from a Christ-like heart. You suggest ‘it might be possible for A to do quantitatively more good than B, and yet for that to count for little in God’s estimation’.

Yet I am wondering why God might make a distinction between a virtuous act by a non-believer and a virtuous act by a believer. Is the effect not the same? Why would God not rejoice to an equal extent in both acts? I am inclined to believe that the object has little interest in whether the subject’s heart is Christ-like or not. If we assume that the effect is the same regardless of belief, how then might it follow that acts performed by non-believers have no/reduced virtue? Should we stop non-believers doing charity runs, for example? Do we believe that a Christian one pound donation to a good cause is worth more than a pound given by an atheist? Should we check that the paramedic has faith before accepting their help? I identify these rather obvious examples not out of any desire to seem facetious but to examine whether God’s (unknown and unknowable) estimation of an act actually translates meaningfully into our own human assessment of its virtue. If it is unknowable then, clearly, it cannot.

As an aside, I would be worried if the virtue of the act depends purely or predominantly on the relationship between the subject and God. This risks self-absorption and narcissism on the part of the subject, one of the very dangers against which you warn us in the piece.

The virtuous act depends not on the worth it brings to the subject but the good it does for the object, which must surely be the over-riding principle.

Welcome to The Hump, Alan! I should point out to others that we’ve know each other for getting on 35 years, so if anything you say offends me I’ll simply post embarrassing pictures of our youthful musical exploits rather than the usual cruel and unusual bloggish punishments like banning!

We can probably resolve a fair bit of apparent disagreement if I clarify that I was intending to differentiate utilitarian ethics from virtue ethics, rather than denying that there is any gradation in virtue (which there must be, if one can grow in virtue). In other words, there is a clear difference in your three Samaritans, but you couldn’t, surely, assume that the guy who gave £20 was twice as good as if he’d given a tenner, and half as virtuous as someone who gave £40. It’s a shame as I rather liked my “virtue cannot be reduced to variables” aphorism, and it falls short of universality ouside its context.

Skipping to your last point next:

Whatever truth there is in that practically, there’s surely another and important side, as Jesus taught when he said that the widow who gave a tiny coin gave more than the rich benefactors had with their silver. As far as the poor recipients went, they’d rather have received the mina than the mite, but we have to ask why God used different measures, and maybe that speaks to the question of Christlikeness.

Bear in mind that in answering GD, I accepted the reality of virtue wherever it is found. But the goal of Christianity (as opposed to the goal of modernism, which is the point at issue more than the believer v. the unbeliever) is to build a future Kingdom of right relationships grounded in God’s love, by calling individuals into the tutelage of Christ in order to make them the kind of people who belong in the Kingdom, starting now. That is, of course, all of grace and comes only through repentance – which is the antidote to narcissism sadly lacking in much that passes for Christianity.

Come the return of Christ, in many ways the “values” of that Kingdom will cut across what we value now (such as rewarding poor widows more than rich philanthropists). I’d contend that this impacts on concepts like “Happiness Index”, which seems to me a very typical attempt at “virtue reductionism”, by defining happiness in terms of what the statisticians, or at best a sample of the population, define as happiness, rather than what Christ (as the final judge) rates. Wikipedia seems to suggest that the people themselves were not consulted: UN politicians enlisted “leading experts in several fields–economics, psychology, survey analysis, national statistics, and more…”. Even Ken Dodd wasn’t invited, and I’d say he was just as qualified.

In that regard you’ll remember that the “Blesseds” of the beatitudes are equally translatable as “Happys”, but the Happiness Index seems to have missed off “hungering and thirsting after righteouness and “being persecuted for righteousness’ sake” in favour of things like economic well-being. Even outside Christianity, the Greek philosophers like Plato contrast the “happy” and “miserable” man in terms of their philosophical virtues, none of which make it to the Happiness Index (nor philosophers either), which is defined in purely secularist terms – namely GDP, social support, healthy life expectancy, freedom to make life choices, generosity, trust and dystopia.

Thanks for the interaction!

George

I’ve replied here since you responded to Alan, but your post appears on the screen above his. I think you’ve touched on a key connection between virtue as “character” and virtue as “good received”.

The two are relationally connected, simply because love is a two way relational street – there cannot be love without a lover and a beloved, nor can there be virtue without a good person and good done to someone.

The problem to which the Kingdom of God is a solution is the loss of love in the world – either the compassion is lost, or the recipient bites the hand that feeds him, or both. In the end, the lesson to be learned is the mutual love of the Godhead – which, most immediately and plainly, we see in Christ’s life and teaching. The believer (by grace, through faith) perceives that the willingness of Christ to die for him/her is a spinoff from the love intrinsic to God.

Build your idea of character formation from there – it involves imitation, the indwelling of the Spirit, obedience to command and teaching, etc. The truly virtuous society (aka the Kingdom of God) is the one in which love is all in all, which necessarily correlates to God being all in all. And it can’t be reached by political or scientific change.

The Church is intended to be a demonstration or downpayment on that society – but that brings us back to “good people in the world”. From the start, the gospel had a political and social role: the historians demonstrate how many of today’s ethical ideals – democracy, compassion for the weak, personal freedom, lack of public corruption etc – have come ultimately through the influence of Jesus.

I first learned that through a friend and scholar Bruce Winter (he was the warden of Tyndale House in Cambridge) who might be described as a sociologist of Roman society in New Testament times. Jesus has been socially/ethically radical wherever he is proclaimed – we lose sight of that in the “post-Christian” west, which Os Guiness pithily describes as a “cut flower culture”, with many beautiful blooms doomed by being cut off from the root.

PS Apologies for so many uses of the rather quaint word “virtue” – it’s not one I customarily use, but it seems the most appropriate in this context.

On the news today – a think-tank estimates that 30% of jobs will be impacted by robotics within the next few years. Which brings to mind another refernce from Gay’s book – modernism characteristically tries to alter humans to fit the society it builds, rather than the society to fit people. It does seem a weird way to run a world, when you consider it!