Jurassic Lark

The Hump is likely to be post-lite this week, as I’m preparing to play two solo guitar sets at the Lyme Regis Folk Festival, at the heart of the Jurassic Coast, as well as leading the civic parade on sopranino sax, in pied-piper style. Don’t ask how that came about since I’ve hardly played folk since the mid 80s. It’s a bit like Pink Anderson or John Hurt being dragged out of their rocking chairs on the Mississippi Delta to play after decades, except that those guys were actually good. Anyway, if you happen to be there on Friday or Saturday, say “Hallo.”

The Hump is likely to be post-lite this week, as I’m preparing to play two solo guitar sets at the Lyme Regis Folk Festival, at the heart of the Jurassic Coast, as well as leading the civic parade on sopranino sax, in pied-piper style. Don’t ask how that came about since I’ve hardly played folk since the mid 80s. It’s a bit like Pink Anderson or John Hurt being dragged out of their rocking chairs on the Mississippi Delta to play after decades, except that those guys were actually good. Anyway, if you happen to be there on Friday or Saturday, say “Hallo.”

Lyme Bay Fish

It was actually in Lyme Regis last week that I saw a minor natural wonder. For some reason a huge swarm of whitebait had formed (must be a good summer) and were filling the entire shoreline, making about a quarter of a mile of water look as if it was boiling. A number of shoals of mackerel were engaged in a feeding frenzy, and small kids were scooping them out in pink rockpool nets, their dads were picking up mackerel with their bare hands, and a chortling angler was reeling in as fast as he could and getting half a dozen mackerel on each cast. The sight from the ornamental gardens was amazing. No profound message there, except the surprising fecundity of nature.

It was actually in Lyme Regis last week that I saw a minor natural wonder. For some reason a huge swarm of whitebait had formed (must be a good summer) and were filling the entire shoreline, making about a quarter of a mile of water look as if it was boiling. A number of shoals of mackerel were engaged in a feeding frenzy, and small kids were scooping them out in pink rockpool nets, their dads were picking up mackerel with their bare hands, and a chortling angler was reeling in as fast as he could and getting half a dozen mackerel on each cast. The sight from the ornamental gardens was amazing. No profound message there, except the surprising fecundity of nature.

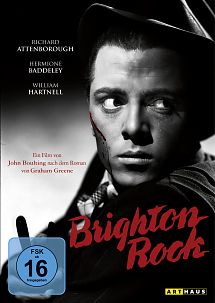

Brighton Rock

Today, I see that Richard Attenborough has died. My tenuous link with him is the 1947 film Brighton Rock, a celebrated pioneer of “stark realism” that personally I don’t rate very highly. But that same year, the guy who is the bandleader in the ballroom scene, Norman Griffiths, who was with my Dad in their first band at school, was also the best man at Dad’s wedding. Somehow I doubt I’ll be invited to Attenborough’s funeral on that account.

Today, I see that Richard Attenborough has died. My tenuous link with him is the 1947 film Brighton Rock, a celebrated pioneer of “stark realism” that personally I don’t rate very highly. But that same year, the guy who is the bandleader in the ballroom scene, Norman Griffiths, who was with my Dad in their first band at school, was also the best man at Dad’s wedding. Somehow I doubt I’ll be invited to Attenborough’s funeral on that account.

Creation and Salvation

Following on, more seriously, from some previous Hump thoughts, I’ve finally finished John Sailhamer’s magnum opus The Meaning of the Pentateuch, which makes a strong and detailed case for a compositional approach to the Pentateuch, concluding that it was from the very start strongly Messianic, the overall message being not so much to record “the Covenant of the Law” as to document its shortcomings and look for a future king who would restore Israel.

Following on, more seriously, from some previous Hump thoughts, I’ve finally finished John Sailhamer’s magnum opus The Meaning of the Pentateuch, which makes a strong and detailed case for a compositional approach to the Pentateuch, concluding that it was from the very start strongly Messianic, the overall message being not so much to record “the Covenant of the Law” as to document its shortcomings and look for a future king who would restore Israel.

This suggests that the New Testament’s Messianic interpretations are neither incorrect, nor even esoteric, but consistent with authorial intent. For example, Sailhamer argues a good case for Matthew’s application of Hosea’s “out of Egypt have I called my son” to Jesus being consistent not only with Hosea’s own Messianic intent, but with that of the Pentateuchal text (Balaam’s oracles) with which Hosea interacted.

A full review would seem to be irrelevant to our purposes here, but one minor thing also caught my eye. One of the things that has moved me towards a more “hands on” view of God’s activity in the natural realm is that there seems no strong reason why he should create nature as a closed system (Robust Formation Economy Principle in Howard Van Till’s parlance), yet remain actively engaged in the business of salvation and personal relationship with believers. Several of us have noted this dichotomy in many expressions of the BioLogos form of theistic evolution, in which God would be incompetent or arbitrary to guide natural events, whilst simultaneously being happily hands-on not only regarding biblical miracles, but in answering personal prayer.

Sailhamer has no interest in that issue in his book at all – his concern is purely Old Testament theology. But he does mark, as an important point, the close links that not only the Pentateuch, but the rest of Scripture, makes between creation and salvation. Even the overall structure betrays this: the Bible starts with creation, turns immediately to sin and salvation, and ends with a new creation. But in detail too this connection is, in his view, a major compositional theme. He alludes briefly and positively to the discovery of cosmic temple imagery in Genesis 1, and links it to the role of the earthly tabernacle in salvation history.

For a more detailed example, Sailhamer sees the poems in the Pentateuch as the “compositional seams” the author uses to keep us abreast of the overall direction of the book. Exodus 15, the Song of Moses after the Red Sea deliverance, is one of those, and Sailhamer points out several literary links back to the creation account. The overall effect is that God’s salvation power is likened to his creation power. Such an analysis (there are many other examples given in the text) emphasizes the question I have asked myself before: why would God act in a completely different manner in creation from the way he acts in salvation?

Answers on a postcard, please.