Here’s me with one of my main guitars. Even most non-guitarists will recognise it as a Fender Stratocaster (though mine is a Tokai copy), the most successful model of electric guitar ever made. It was released in 1954, and remains the worldwide market leader, pretty much in its original form. Even Fender’s “improvements” have proved unable to compete with the original post-war technology. To what can one attribute its 60 year dominance of a crowded market?

Here’s me with one of my main guitars. Even most non-guitarists will recognise it as a Fender Stratocaster (though mine is a Tokai copy), the most successful model of electric guitar ever made. It was released in 1954, and remains the worldwide market leader, pretty much in its original form. Even Fender’s “improvements” have proved unable to compete with the original post-war technology. To what can one attribute its 60 year dominance of a crowded market?

As a guitar nerd I could give some account, if asked. But what if you were completely ignorant of design and marketing considerations, iconic endorsees, nostalgia, and so on? Or worse still, what if, as in evolution, one were forbidden in principle to consider teleology at all, and compelled to look merely at the mechanical structure (and perhaps its provenance in the older Tecaster/Broadcaster design), and the effects of the “environment”?

You’d be denied explanations like “Leo Fender just got it right first time.” He certainly could never have predicted how things in musical culture would turn out. So you might conclude that the constantly changing “environment” selected a guitar that, effectively, was random with respect to fitness. That, of course, would tell you nothing useful either about the environment or the design. If you doubt that, can you explain why the Epiphone Olympic Special doesn’t rule the electric guitar world? “The environment provides the information” isn’t an explanation that helps me very much – maybe it helps you?

Worse than that, knowing as a matter of fact that Leo did design the thing with his own ideas of what was desirable in a musical instrument, one could reverse the theory and say that it was the environment that was random with respect to a definite purpose, and that in this case that purpose was sufficent, above those of rival makers, to survive the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune.

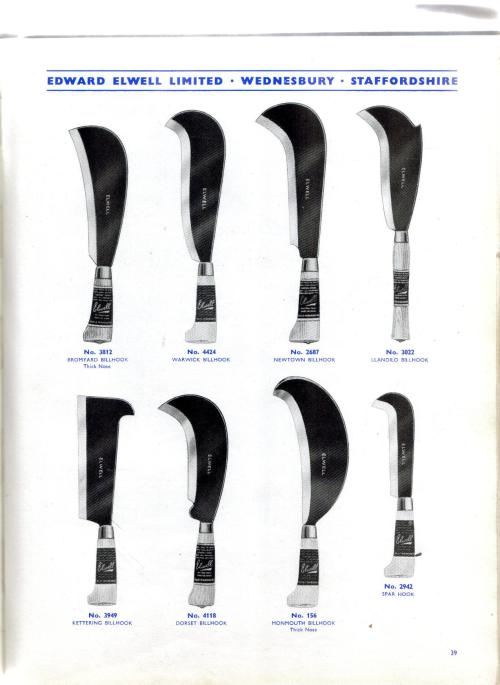

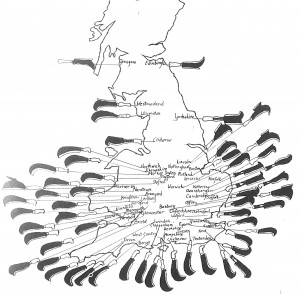

Here’s another technology picture that demonstrates the nebulosity of the fitness metaphor. It’s an odd fact that in Britain the humble billhook, historically, has highly regional patterns – don’t let a hedger here in Devon dare show his hedging tool across the border in Cornwall. Similar significant variations occur in other tools – I remember wondering at the rectangular trowel my Swiss bricklayer friend used, compared to the kite shape universal over here. Sociological reasons would appear the only likely explanation for this, since it’s doubtful that either hedge-branches or walls differ regionally. But if such considerations were excluded, as in biology, any adaptive explanations might well be assumed but deemed too complex to be researched in detail – though a plausible narrative would be considered in order.

Here’s another technology picture that demonstrates the nebulosity of the fitness metaphor. It’s an odd fact that in Britain the humble billhook, historically, has highly regional patterns – don’t let a hedger here in Devon dare show his hedging tool across the border in Cornwall. Similar significant variations occur in other tools – I remember wondering at the rectangular trowel my Swiss bricklayer friend used, compared to the kite shape universal over here. Sociological reasons would appear the only likely explanation for this, since it’s doubtful that either hedge-branches or walls differ regionally. But if such considerations were excluded, as in biology, any adaptive explanations might well be assumed but deemed too complex to be researched in detail – though a plausible narrative would be considered in order.

And once again, the fact that the regional environment was, actually, random with respect to the proudly maintained local design of the tools would easily be misconstrued as the tools being random with respect to the environment: indeed, they’d be a good example of non-adaptive drift.

I’ve just started reading Arthur Russell Wallace’s The World of Life, which begins with a long and thorough section on the worldwide distribution of plants. One can see how this contributes, still, to an evolutionary view of life. For example, finding tens of species in a small square, a hundred or so in one field, and so on up the scale, with associated changes in frequency from ubiquitous to rare, it’s hard to maintain an idea that each species is placed in a unique and fixed niche. It’s easy to document what Wallace like Darwin calls, teleologically, “the struggle for existence,” as the plants unsuited to their particular setting perish whilst others prosper.

Other evidence is, of course, required to show actual evolutionary change in organisms rather than simply this attrition of existing forms, but that idea too is not so hard to support as a generality. What becomes more problematic is to pin down anything like scientific detail in this tangled evidence, to explain change in terms of “natural selection”. To assume that the organisms vary non-purposively and that the environment is a “blind watchmaker” is, without such detailed accounts, rather than the ubiquitous Just So stories, mere philosophical prejudice.

It could equally be the case that organisms vary according to distinct purposes (whether by internal teleology or external), but that the environment is sometimes “random” with respect to those purposes (ie it exhibits unexpected features relative to design) , as is the case in guitar or billhook design. And that’s a rather different theory from Darwinism.

Stephen Talbott, whom I’ve reference here before, has just published another article on New Atlantis, which also examines the intractable vagueness of the “fitness” at the heart of traditional evolutionary theory, and the impossibility of attributing “randomness” in relation to it apart from a prior commitment against teleology.

It says nothing dramatically new, but then neither do the replies of the materialists, of which I’ve seen enough now to consider them inadequate, if not simply desperate. It helps cut them down to size, perhaps.