I’ve already suggested that we ought to do a full review of John Walton’s important new book, Lost World of Adam and Eve here. But since it consists of 21 propositions, it’s maybe less daunting to make a cautious start by mentioning the “excursus” in Proposition 19 by celebrated New Testament scholar N T Wright.

You’ll probably be aware that Tom Wright, formerly Bishop of Durham, is one of the most prominent theological proponents of orthodox Evangelical teachings. That in itself is controversial nowadays, but he has also attracted dissension because he is not afraid to challenge received Evangelical wisdom head-on where he thinks it goes against the truth of Scripture. I’m quite sure he doesn’t always get it right, but he works on the right issues in the right way.

You’ll probably be aware that Tom Wright, formerly Bishop of Durham, is one of the most prominent theological proponents of orthodox Evangelical teachings. That in itself is controversial nowadays, but he has also attracted dissension because he is not afraid to challenge received Evangelical wisdom head-on where he thinks it goes against the truth of Scripture. I’m quite sure he doesn’t always get it right, but he works on the right issues in the right way.

That Wright contributed to Walton’s book is, in itself, a measure of the worth of Walton’s work. In fact, in discussing the central calling of Adam – which relates to serving and developing the sacred space of God’s creation as his image-bearer – Wright specifically cites three names in modern scholarship: Walton himself, Greg Beale (another hero of mine whose work on biblical temple imagery I’ve covered here) and J Richard Middleton, who is a supporter of The Hump and has commented occasionally. I’ve also reviewed Middleton’s own recent book, if rather inadequately.

Wright’s brief from Walton was “the use of Adam by Paul”, centred especially on Romans 5, which is an important passage because it deals with the role of Adam more than any writing of the pre-Christian era after Genesis. Christian views of Adam and the Fall derive principally from Paul’s innovative understanding.

This passage, together with the other scattered references in Paul, has been seen as an important indicator of the historical reality of Adam. Scholars like Peter Enns have taken the line that Paul probably believed wrongly in Adam’s concrete existence, being a child of his time, but that it somehow doesn’t affect the inspiration of Scripture even if it weakens his actual argument. Others have said that Paul’s argument simply doesn’t work if a real Christ is paralleled with an allegorical Adam, and that thereby Scripture becomes so culturally bound that “inspiration” is stripped of any real content.

Wright, like Walton, appears closer to the latter group, arguing from the ANE concept of “archetype” rather than the much later idea of “allegory” that Adam is “the representative” of mankind as a person – as opposed to being “representative” of mankind in the abstract. In neither Wright’s nor Walton’s case does that argue for a strict historical literalism in the Genesis account.

But in fact, in his excursus Wright stresses, as biblical scholars should, not how Paul’s theology can speak to matters that interest us, like the historicity of Adam, but what Paul himself is interested in teaching. And the central point of his argument is that, whereas we tend to regard Romans 5 as teaching about the origin of sin and the means of salvation from sin, Paul actually intended something wider, primarily about the Kingdom of God.

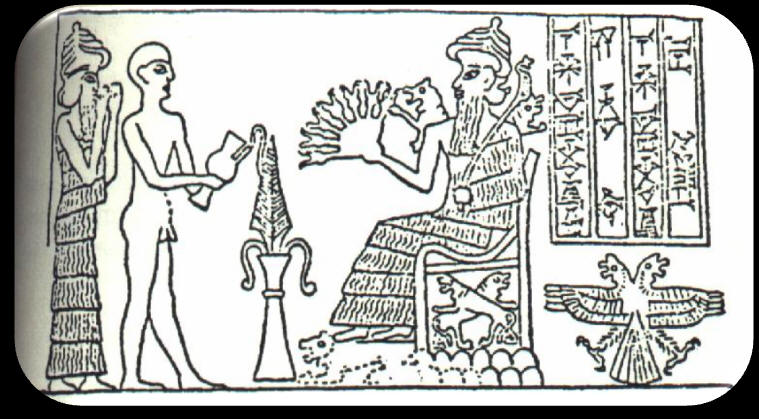

I won’t reiterate his examination of the text(s), but he shows how the discussion of sin is, as in Genesis itself, set in the wider context of God’s purpose in creation. The background of Genesis is the intended role of man as God’s vice-regent in not only preserving, but completing, God’s “cosmic temple”, under God bringing what remains of unorder (tohu wabohu) into God’s cosmic order. The aim was always that all things should be united under God’s reign.

I won’t reiterate his examination of the text(s), but he shows how the discussion of sin is, as in Genesis itself, set in the wider context of God’s purpose in creation. The background of Genesis is the intended role of man as God’s vice-regent in not only preserving, but completing, God’s “cosmic temple”, under God bringing what remains of unorder (tohu wabohu) into God’s cosmic order. The aim was always that all things should be united under God’s reign.

But sin, apart from being a disaster for humankind itself, also interrupted that work by introducing disorder and rebellion against God’s rule. The history of salvation, then, culminating in the incarnation, passion and glorification of Christ, is indeed about salvation from sin, but always with the purpose in mind that we should be restored, in and with Christ, to the perfection, or completion, that Adam missed. This achieved, the project proceeds to its original eschatological goal. Paradoxically, the tragedy of sin brings even greater glory to God, and his Son, than Adam’s obedience would have done.

All this is, to me, incontrovertible in Paul’s writing, once I re-examine the text wearing the spectacles that Wright provides. The chapter provides a welcome re-orientation to those who have been too closely focused on the gospel as “personal forgiveness”, and even more to those who can’t look at Scripture without irrelevantly dragging science into it.

On one minor point (and that in relation to science) I found myself questioning Wright on the basis of his own methodology, and his own view of biblical inspiration. Moving on to the vocation of the actual Adam, Wright seems to nod to C S Lewis’s speculations, with which some may be familiar. Wright, describing how Israel would recognise Adam’s story as like their own, suggests a provisional scenario:

This leads me to my proposal: that just as God chose Israel from the rest of humankind for a special, strange, demanding vocation, so perhaps what Genesis is telling us is that God chose one pair from the rest of early hominids for a special, strange, demanding vocation. This pair (call them Adam and Eve if you like) were to be the representatives of the whole human race, the ones in whom God’s purposes to make the whole world a place of delight and joy and order, eventually colonizing the whole creation, were to be taken forward… If they failed, they would bring the whole purpose for the wider creation, including all those other nonchosen hominids, down with then… Not that death, the decay and dissolution of plants, animals and hominds, wasn’t a reality already; but you, Adam and Eve, are chosen to be the people through whom God’s life-giving reflection will be imaged into the world…

Now in general this proposal makes a good deal of sense to me, and runs along the lines I’ve developed for myself over the last five years or so. But his threefold use of the biological term “hominid” inevitably leads one into a particular prehistoric interpretation of the idea, in which Adam and Eve are buried in deep time, perhaps around the time of the emergence of Homo sapiens, or even earlier. Possibly much, much earlier, in fact, since the term Hominidae encompasses not only the genus Homo and the Australopithecines, but all the great apes. Even had Wright used the more restricted word “hominin” the story of sin – and, even more importantly, the image-bearing and vocation of mankind – will tend to be set way back in anthropology, rather than in history.

This is quite unnececessary, given the fact that Wright’s proposal removes any “Creationist” need for a single human progenitor or for a primordial golden age, and I see many problems with it. These cover many areas: the first is the lack of any evidence for the conscious worship of any named gods before the Neolithic period, tens of thousands of years later than any time when the word “hominid” would be appropriate other than as a way of distinguishing the “called” from the “uncalled” humans.

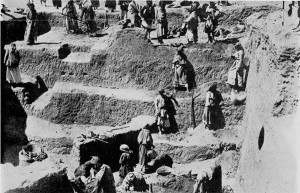

Then one must consider the proto-historical features of Genesis, which for all its ANE “mythological” genre elements treats its archetypes, Adam and Eve, as people in a particular place and time. This is comparable to the Epic of Gilgamesh, in which Gilgamesh is a king mentioned in the ancient king lists. Likewise, Adapa, the sage of Eridu, is historically situated as the first in a line associated with the foundation of a real city at the time and place indicated in the ancient texts, according to archaeology. Even the Flood, in the ANE, is treated as a specific event (King Ashurbanipal had pre-flood texts in his library) which correlates with the local archaeological evidence at Shuruppak for a flood c2900BC.

Then one must consider the proto-historical features of Genesis, which for all its ANE “mythological” genre elements treats its archetypes, Adam and Eve, as people in a particular place and time. This is comparable to the Epic of Gilgamesh, in which Gilgamesh is a king mentioned in the ancient king lists. Likewise, Adapa, the sage of Eridu, is historically situated as the first in a line associated with the foundation of a real city at the time and place indicated in the ancient texts, according to archaeology. Even the Flood, in the ANE, is treated as a specific event (King Ashurbanipal had pre-flood texts in his library) which correlates with the local archaeological evidence at Shuruppak for a flood c2900BC.

The genealogies of Genesis may be (as Walton suggests) stylised, idealised or abridged, but they indicate historical awareness and the recounting of events within human memory, rather than the story of the fossils. This brings me to my main quibble, as far as N T Wright is concerned as a biblical scholar. And that is, what view of inspiration must one take if whoever wrote Genesis was led by the Spirit to narrate in an historical setting a story that did, indeed, occur, but far beyond the reach of any human recollection? And why would God wait so many millennia before starting the engine of salvation?

It’s rightly objected that to look for the Big Bang or heliocentrism in Genesis, when any conceivable author would have had no knowledge whatsoever of such things, is unhelpful. In fact, the whole thrust of John Walton’s project is that one should approach the texts first from the viewpoint of the ANE culture in which they arose. It is, of course, true that God could give new scientific insights or dictate forgotten history, as the scientistic Atheists insist upon to countenance inspiration at all. But having shown that that’s not the way God has ever worked, why would Yahweh plant the far-from-self-evident account of a palaeolithic attempt at covenant in the prophet’s mind – yet stripped of its real context and enrobed with a complete new setting?

Far more likely, surely, that divine inspiration (which as Charles Hodge said works not just through “interference” with the author’s mind but by the preparation of his whole life, and even his whole culture) should have used traditions and documents preserved through the descendants and successors of those to whom they happened.

So, to my mind, Wright’s talk of “hominids” is more likely to obfuscate our understanding of covenant and salvation history – including his own excellent proposal for its interpretation – than to illuminate it. My own proposal is that the kind of Adam Wright proposes would sit very nicely in third millennium BC Mesopotamia, right where Genesis puts him.

Jon, I wonder about the timing issue, and if its as important as you indicate. True that the writers of Genesis would have had no knowledge of hominims, let alone hominids, or how many millenia had passed from the evidence of modern human spiritual and higher order cognitive abilities. But they might have known that there was a time before there were cities or even agriculture. They must have considered this, or the whole idea of beginning, the main theme of Genesis would make no sense. I am also not convinced that they were speaking of known history before Genesis 11 (as seems to be a consensus). So I dont think its terribly far fetched to place Adam somewhere around 50,000 ya, even without considering the role of God in inspiration of the text.

Hi there, Sy

In the end the placing of Adam and Eve into the history we reconstruct in our age is of limited importance, of course. That they existed, in my view (and I think that of Walton and probably Wright) affects the nature of the world, sin and salvation. When they existed is more a question of apologetics and rational faith. Just as, whilst believing in Christ will save us, seeing that he fits into a first century Judaean timeline will both help our belief, and probably add to our understanding of his teaching and actions.

My argument – what in old English idiom we’d call my “two pennyworth” to show it’s an offering, not a pontification – is that not only the biblical writers, but ANE scribes in general, were well aware of historical traditions – but not as “history”, which was a later invention, but in mythic or epic genre.

So to your point about awareness of pre-civic life I’d say “Amen” – the Sumerian myths are often about the founding of the first cities, like Eridu, with a folk-memory that before that (which included the “kingship descending from heaven”), all was chaos, just as we view the early mediaeval period as the “dark ages”. But to the earliest Sumerian writers, it was literally just a few centuries in the past. The same vibe seems to me to exist in Genesis, and my point is that the kind of Adam Walton or Wright describe would sit perfectly well in that setting.

Third millennium Mesopotamia is a uniquely significant place, seeing the foundation of cities, writing, maths, astronomy and so much more – including communications, of course, seeing that Adam’s legacy spread to all men, not just amongst an isolated hunter-gatherer group. It also happens to have been, a millennium or so later, the reputed birthplace of our spiritual father Abraham.

My larger “historical” objection to the “palaeolithic Adam” idea is that it only seems necessary at all in order to explain things like the origin of human imagination, art etc, which Genesis isn’t about, once one gets away from Adam as “the first man” and sees him as the one who introduced the covenant relationship with Yahweh, and its repudiation, sin.

Conversely, if one adopts an Adam back in the Ice Age, once has to explain how (as far as we understand things) all knowledge of Yahweh was then lost until Abram, and indeed all knowledge of actual gods until the neolithic. How come totemism, shamanism and magic are all we find evidence for over tens of thousands of years, and where was the line of people that kept the flame burning for Yahweh, as we find in Seth’s line leading down to Abraham in the Bible?

But if 50K years is legit, then so would be the 3m years they’re now suggesting for the first tools. By what criteria would one make a preference? I’d say it should be on the basis of what Genesis 2 is actually about, which is a new personal relationship with Yahweh.