I find myself reading an old (1956) book by psychologist A. M. Meerloo, The Rape of the Mind – the Psychology of Thought Control. His study of the techniques of individual mind control under Naziism and, particularly, Communist brain-washing – which he more correctly calls “menticide” – arose from his first-hand experience as a Dutch resistance worker and later examiner of both Nazis and Communists.

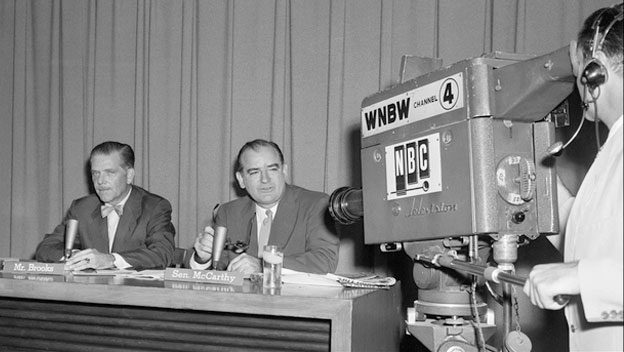

But he goes beyond this demonic application of new scientific knowledge of the mind to the techniques of mental mass-control exercised by totalitarian regimes over their populations. Even more significantly for us, he documents the deliberate use of similar techniques in supposedly free countries by politicians, commercial advertisers and special interest pressure-groups. Bearing in mind that he was writing in the early days of both mass-media television and social psychology, he was highly prescient about the increasing dangers to human freedom and dignity from these tools. Just as the New Media can be powerfully harnessed to create radical terrorists, so the rest of us can be subtly manipulated to believe – well, that we’re free from manipulation.

But he goes beyond this demonic application of new scientific knowledge of the mind to the techniques of mental mass-control exercised by totalitarian regimes over their populations. Even more significantly for us, he documents the deliberate use of similar techniques in supposedly free countries by politicians, commercial advertisers and special interest pressure-groups. Bearing in mind that he was writing in the early days of both mass-media television and social psychology, he was highly prescient about the increasing dangers to human freedom and dignity from these tools. Just as the New Media can be powerfully harnessed to create radical terrorists, so the rest of us can be subtly manipulated to believe – well, that we’re free from manipulation. What is worrying is our lack (as ordinary individuals) of any serious concern to identify and understand such mind-control at work in our own case, despite the astonishing and otherwise inexplicable changes to public values, which seem to leave people unaware that anything has changed in their thinking. Why are we so surprised when people in other cultures espouse moral values that we only rejected last year? How did we come to consider not only that torture might be a necesssary evil, but that it always was held to be so by everyone? Why do we so often fail to spot the incongruity between trumpeting the rights of the disabled and aborting most Downs’ syndrome babies?

What is worrying is our lack (as ordinary individuals) of any serious concern to identify and understand such mind-control at work in our own case, despite the astonishing and otherwise inexplicable changes to public values, which seem to leave people unaware that anything has changed in their thinking. Why are we so surprised when people in other cultures espouse moral values that we only rejected last year? How did we come to consider not only that torture might be a necesssary evil, but that it always was held to be so by everyone? Why do we so often fail to spot the incongruity between trumpeting the rights of the disabled and aborting most Downs’ syndrome babies?

In reading the book, the sheer power of “mass suggestion” was actually most graphically shown by one instance in which the author himself unknowingly succumbed to it. Writing on the very subject of the power of the media to deceive, Meerloo says:

Radio and television have enhanced the hypnotizing power of sounds, images, and words. Most Americans remember very clearly that frightening day in 1938 when Orson Welles’s broadcast of the invasion from Mars sent hundreds of people scurrying for shelter, running from their homes like panicky animals trying to escape a forest fire. The Welles broadcast is one of the clearest examples of the enormous hypnosuggestive power of the various means of mass communication, and the tremendous impact that authoritatively broadcast nonsense can have on intelligent, normal people.

Now in 1938 Meerloo was still practising in Holland, but nevertheless he appeals to the common experience and memory of Americans, which appears, in the light of later careful research, to be entirely false. Check out this article from the Daily Telegraph.

Reading that piece, it seems that the real mind-control was not exercised by Orson Welles at all (though it did his reputation no harm to go along with that myth in later life), but by the newspapers, which, it seems, puffed up the “universal panic” story primarily in order to discredit the competing medium of commercial radio as dangerous to society and to truth. How well they succeeded is shown by the fact that most of us still believe them (and are completely unaware of the exposure of the truth), as did Meerloo. If he can be fooled, any of us can. I wonder how many Americans became convinced that they had personally experienced the public panic that never, apparently, was?

I leave this piece with some more general words from Meerloo’s book, upon which it would be good to reflect in this internet age, not only concerning how we adopt political and moral views within current society, but how, on the smaller scale, our attitudes to issues arising in religion or science may be tweaked by those who, perhaps consciously (or perhaps nowadays, unconsciously adopting what has become normal methodology) seek to bypass rational enquiry, or even legitimate authority. Now, more than ever, we need to know why we believe what we believe.

I leave this piece with some more general words from Meerloo’s book, upon which it would be good to reflect in this internet age, not only concerning how we adopt political and moral views within current society, but how, on the smaller scale, our attitudes to issues arising in religion or science may be tweaked by those who, perhaps consciously (or perhaps nowadays, unconsciously adopting what has become normal methodology) seek to bypass rational enquiry, or even legitimate authority. Now, more than ever, we need to know why we believe what we believe.

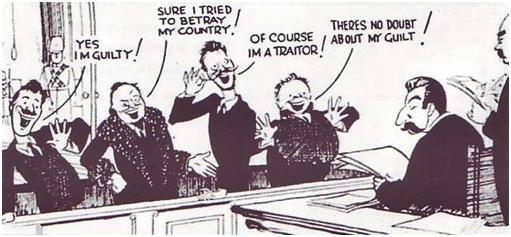

“Speech manifestations represent conditioned reflex functions of the human brain.” In a simpler way we may say: he

who dictates and formulates the words and phrases we use, he who is master of the press and radio, is master of the mind.In the Pavlovian strategy, terrorizing force can finally be replaced by a new organization of the means of communication. Ready made opinions can be distributed day by day through press, radio, and so on, again and again, till they reach the nerve cell and implant a fixed pattern of thought in the brain. Consequently, guided public opinion is the result, according to Pavlovian theoreticians, of good propaganda technique, and the polls a verification of the temporary successful action of the Pavlovian machinations on the mind. Yet, the polls may only count what people pretend to think and believe, because it is dangerous for them to do otherwise.

I’ve sometimes wondered if the entrance of far-right or far-left candidates into our various elections here in the U.S. wasn’t a sneaky (cooperative) way to make a mere leaning candidate in that direction look much more moderate, and therefore less out-of-bounds to those who want to feel moderate. But you present a kind of flip side here where somebody might pull levers to encroach or limit the acceptable range rather than to explode it. Very interesting indeed.

Given that only a small percentage of people over here would still be living who are old enough to remember the Wells event first hand, the mythologized newspaper accounts and recorded history has been our surrogate cultural memory. I guess it should be no surprise that at that level memory shows its faults as well. The individual human mind sometimes “knows” what it is supposed to remember and voila! The mind inserts what it needs to bring actual memories into line. I had never been aware of this cultural example of the same thing. Thanks.

Been away for a while at a camp. Tis the season for such activities.

Hi Merv – hope camp was good. As my straight talking grandmother used to say when we’d not visited for awhile, “I thought you was dead!”

Writing the piece, I thought of the possibility that the real fake story was the Telegraph’s debunking of the Welles myth, but life can’t get that hard, surely!

There’s also a parallel with those scientific myths like the Scopes trial, and even the Galileo affair. I guess Churchill was right – “The price of freedom is eternal vigilance.”

The quote by Chomsky reminded me a bit of this one I saw today:

“If you don’t want a man unhappy politically, don’t give him two sides to a question to worry him; give him one. Better yet, give him none. Let him forget there is such a thing as war. If the government is inefficient, top-heavy, and tax-mad, better it be all those than that people worry over it…. Give the people contests they win by remembering the words to more popular songs or the names of state capitals or how much corn Iowa grew last year. Cram them full of noncombustible data, chock them so damned full of ‘facts’ they feel stuffed, but absolutely ‘brilliant’ with information. Then they’ll feel they’re thinking, they’ll get a sense of motion without moving. And they’ll be happy, because facts of that sort don’t change.”

― Ray Bradbury, Fahrenheit 451

From this article:

https://www.lewrockwell.com/2015/06/john-w-whitehead/the-final-link-in-the-chain-around-your-neck/

Cath Olic

The book by Meerloo cited in the OP speaks to that theme, and (at the very start of the TV age) describes how empty diversions predispose the mind to being controlled by others – and how deliberately that fact is employed by those desiring such control.

But centuries before, Blaise Pascal said the same in spiritual terms: