In my last post I suggested that failure to deal adequately with the implications of monotheism itself leads directly to many erroneous ideas in both theology as such and in understanding the relationship of God to creation, including evolution.

I used the analogy of God as author to show how one should see God as not “a Being within reality”, but the being whose reality – himself – creates our entirely different, subordinate reality. That is why it is possible for God’s will to lie behind everything – including what we will – without reducing us to automata. I also spoke of the shortcomings of that analogy, in that an author can only appear to interact with his characters by writing himself as a character in their reality. Whilst that has intriguing possibilities for understanding more of revelation and the Incarnation, it suggests that it is not possible to have real relationship with God, and in that the analogy is false.

The logic of the author metaphor has been understood before: I was reading today how C S Lewis, before becoming a theist and then a Christian, tried to have his cake and eat it, once he realised the emptiness of materialism, by following a popular fad for “The Absolute”, which was, as it were, God without the personhood (and the consequent demands upon our own lives). These intellectuals argued that God could no more relate to us than an author could to his own created characters. They were clearly wrong (and “The Absolute” in that form has now disappeared into the abyss of damned philosophical demons). But it’s not immediately obvious why it’s wrong. I suggest it may be because we don’t understand the difference between God’s creation and authorship any more than we do that between creation and artisanship.

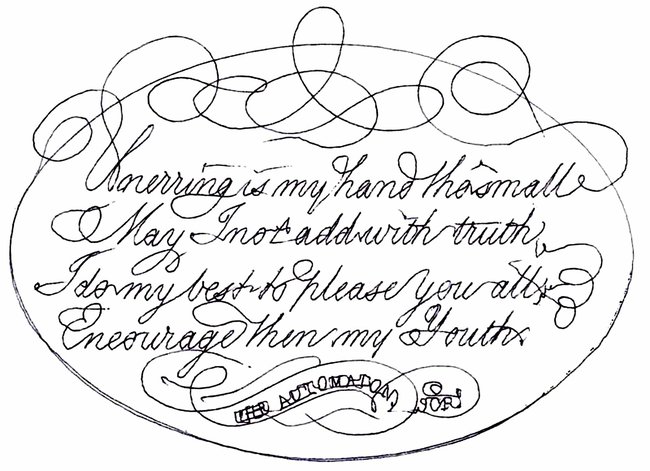

Coincidentally (I do love the synchronicity that pervades life) I recently saw the film Hugo when my daughter brought us the DVD to watch. Never knowingly in touch with cultural fashion, I’d never even heard of the film, though it’s five years old. A charming fantasy, the plot nevertheless touches base in the reality of the life of the early film-maker Georges Méliès, but the real star is a broken automaton supposedly made by him (Méliès certainly did make automata) but actually based on that made around 1800 by the Swiss clockmaker Henri Maillardet in London. That story is at least as fascinating as that of the film, for when delivered in fire-damaged pieces to The Franklin Institute in 1928, the automaton was attributed to Johann Maelzel, who genuinely invented the metronome and fraudulently invented a chess-machine. Only when painstakingly reconstructed and able to perform its repertoire of four intricate drawings and three poems did the final poem of the automaton reveal the name of its actual maker, Maillardet.

If you’re unfamiliar with the machine, you really should check out this clip.

For our purposes, the interesting thing is that the eighteenth century obsession with automata was more than a fad for intricate mechanisms: it had a serious philosophical basis in the belief that physical reality was, with the possible exception of the human soul, no more than a mechanism. This analysis of the reason for the prevalence of automata appears to be widely accepted, and is attributed in large parte to Descartes. As Wikipedia‘s article on automata puts it:

A new attitude towards automata is to be found in Descartes when he suggested that the bodies of animals are nothing more than complex machines – the bones, muscles and organs could be replaced with cogs, pistons and cams. Thus mechanism became the standard to which Nature and the organism was compared…

The world’s first successfully-built biomechanical automaton is considered to be The Flute Player, invented by the French engineer Jacques de Vaucanson in 1737. He also constructed the Digesting Duck, a mechanical duck that gave the false illusion of eating and defecating, seeming to endorse Cartesian ideas that animals are no more than machines of flesh.

In his Treatise on Man, Descartes wrote:

I should like you to consider that these functions (including passion, memory, and imagination) follow from the mere arrangement of the machine’s organs every bit as naturally as the movements of a clock or other automaton follow from the arrangement of its counter-weights and wheels.

To Descartes, only the immaterial soul of man was excepted from this mechanistic – even clockwork – conception. The ability of man to perform a whole range of tasks (rather than the automaton’s restricted range, even if in these it might out-perform a human) and to use the gift of language in solving unfamiliar problems was all that enabled one to distinguish a person from a machine – much the same as in today’s Turing Test.

But the attempts to make machines to beat the Turing test are only one aspect of the evidence that Descartes’ mechanistic philosophy is still alive and well, and more pervasive than ever in an academic world that largely rejects the human soul’s existence. Artificial Intelligence aside, the reduction of living things to mere collections of molecular machines is a trap into which not only mainstream biology, but even Intelligent Design (following the general scheme of William Paley), has tended to fall.

There is, if you’ll bear with me, a parallel between this mechanistic view of nature and the theological problem people have with a sovereign God, above and beyond the pervasive metaphor of true “free will” as the antithesis of being created “robots”. Both draw too close an analogy between the work of artifice and the act of creation. Whether one is an atheist seeing natural selection as nature’s Henri Maillardet, honing the biological machines of the cell, or a believer seeing the same mechanisms as God’s direct or indirect work, one is still, perhaps, failing to see that the two kinds of making – artificing and creation are fundamentally different in their results as well as, or more than, their means.

Scripture does, of course, represent God as a workman, laying the foundations of the earth, knitting the foetus together in the womb, and so on – that is the closest, perhaps the only, analogy we have to creation. Likewise, even before Descartes it was obvious that legs act as mechanical levers for walking: the machine analogy has indeed some validity in the biological world, as Paley rightly perceieved and demonstrated long before James Shapiro’s natural genetic engineering or discovery of the flagellar motor or algorithmic processing in cells..

But in the end, to be a created organism is much more than to be a set of molecular machines individually put together by evolution, like the machinist at the Franklin Institute who rebuilt Maillardet’s drawing boy. That’s the true weakness of the genetic model, which is thoroughly Cartesian in its conception. Creation is not just a method of manufacturing artifacts – it is an alternative activity, resulting in a qualitatively different result – an integrated being, which Maillardet’s boy, despite the poignancy he excites, can never be. He is an automaton – and even the lowliest animal is not.

This, it appears to me, is Descartes’ biggest mistake – not in attributing rationality only to an implanted eternal soul (quite different from the biblical conception in any case), but in failing to see that both human reason and living bodies are finally non-mechanical because created by God. And so God could certainly create through evolution, as he creates people though natural generation – but he could not create by evolution, if that is conceived as an essentially mechanical or chemical process. Creation transcends mechanics.

And so to the parallel with human choice. The question of how God can be sovereign over our “real” choices without making us robots is answered not by elevating free-will to an unbiblical autonomy, but by a greater understanding that we are created beings, not manufactured robots, and so the relationship between maker and made is of a quite different order. It may be a tricky concept to understand, but is not that much more difficult than perceiving that our bodies are “real” in a way that an automaton’s is not, even though, in Christian understanding, they are sustained in existence moment by moment only by God’s active will (even the weakest Christian position, “mere conservationism”, believes that). And even though, unlike the automaton, we cannot be put together again from fire-damaged parts by clever mechanics after two centuries, we have a kind of reality that it does not, even in principle.

We need to recover the wonder of knowing how different is is to be a creation of the living God, rather than one of Descartes’ clockwork automata – and that applies to trees and dogs, as well as sons of Adam.

“And so God could certainly create through evolution, as he creates people though natural generation – but he could not create by evolution, if that is conceived as an essentially mechanical or chemical process. Creation transcends mechanics.”

I’m not getting the distinction between God creating *through* evolution and God creating *by* evolution.

Also, I think “machine” may be due more respect or consideration. Almost by definition, a machine requires a designer and is intended to accomplish a purpose. Like, totally teleological.

Cath

The distinction is partly about sufficiency of means, and partly about the nature of the outcome. To cite the procreation example, all the genetics and biology is a necessary part of God’s means, but insufficient to account for God’s creative purpose in forming the prophet Jeremiah or King David. Or us.

Regarding outcomes, generation itself is a natural (in the Aristotelian sense) outworking of creation, and produces more than an assemblage of chemicals and genetic information, but rather a holistic being… and (contra Descartes) that’s true for animals and plants as well as people.

I’m not averse to the machine analogy, given that creatures are never less than machines, but more. In my old work, biomechanics was a useful tool in understanding back problems – but woefully insufficient as an understanding of the body.

As Intelligent Design people themselves concur, machines indeed require a designer – but not necessarily God. An alien within creation could, in theory, construct molecular machines, and II people flatter themselves they’ll make a robot that passes the Turing Test. But only God can create anything, firstly because he creates in the first instance ex nihilo, and secondly because even when creating through existing means, or through existing materials (water into wine, for example) he creates whole instances of “being”, and the whole reality in which they exist.

Design is still our best analogy, because as you say it establishes finality: an idea in God’s, or the created designer’s, mind becomes reality. But the mere designer achieves his ends by “putting things together” to make a machine, and only God creates to make an entity. This is, for the most part, a return to Aquinas’ way of looking at things. It’s much disparaged by Cartesians, but I think is beginning to look necessary again as reductionist science shows in inability to explain anything much in biology at a deep level.

By the way, I didn’t talk like this when doing Romans 9 yesterday, which is probably why it seems to have been much appreciated by the folks.

Jon,

I *think* I know what you mean.

God creating *through* evolution would be God using certain natural/material means *as part of* the ingredients of bringing new life into the world; the other ingredients would be his supernatural/spiritual input, His “ensoulment” of the living being.

Whereas, God creating *by* evolution would be God allowing nothing but natural/material means to bring new life into the world; these natural/material means would naturally produce the life/soul of the living being.

Close?

If the first formulation is true, then God is *actively* involved, not passively involved, in bringing each being into the world, whether it’s Jeremiah, King David, us, or an animal or plant. I’m not sure this would sit well even with the post-neoDarwinian, new wave “structuralists”.

P.S.

Did your Romans 9 lesson touch on the sobering verse 27?

[“And Isaiah cries out concerning Israel: “Though the number of the sons of Israel be as the sand of the sea, only a remnant of them will be saved”]

It reminds me of Jesus’ sobering words –

“Enter by the narrow gate; for the gate is wide and the way is easy, that leads to destruction, and those who enter by it are many. For the gate is narrow and the way is hard, that leads to life, and those who find it are few.”

Not far off. The active involvement of the Creator in Creation is, as far as I can see, the distinctive of Theism against Deism. Precisely how that happens is a secondary matter.

All along I’ve been seeking to make that distinction in discussions here and at BioLogos, as being far more central than “whether evolution is true”, as if evolution ever saved anyone. Historically, theistic evolution was clear on God’s involvement – even the spiritualist Wallace was convinced of God’s ultimate governance of each and every outcome of natural selection (so that, for example, he determined that the various woods of trees would benefit mankind in specific ways).

There are still TEs – I suspect a majority in the pews, who don’t have a specific interest in the field – who are thoroughly theistic in that sense. One writer who springs to mind is David L Wilcox, an Evangelical (Reformed) population geneticist active in the ASA but, somehow, not cited much on BioLogos. And of course, the writers here. That’s the “Providential” in “Classic Providential Naturalism”.

I’ve still not read Denton’s new book, and his religious position seems equivocal – but I gather he specifically admits the insufficiency of structuralism as a total explanation of life, and points to the work of ID in showing the requirement for active teleology – though not committing himself to that alone, either.

On your other point, I did indeed cover v27, which is central to Paul’s overall argument in Romans 9. His emphasis is on the remnant being chosen by grace: Jesus in the other verse majors on the choices that result from grace.

“The active involvement of the Creator in Creation is, as far as I can see, the distinctive of Theism against Deism. Precisely how that happens is a secondary matter.

All along I’ve been seeking to make that distinction in discussions here and at BioLogos, as being far more central than “whether evolution is true”…”

However, going the other way, I think, is something I believe St. Thomas Aquinas said in “Summa Contra Gentiles”:

‘The WAY that God created the world reveals God’s character.

A wrong understanding of the WAY that God created the world reflects a false understanding of God.’

Interesting.

(I started thinking of how Scripture always, I think, shows God by his word creating things *quickly*, even instantaneously. I’ll try to ponder this a bit more.)

“On your other point, I did indeed cover v27, which is central to Paul’s overall argument in Romans 9. His emphasis is on the remnant being chosen by grace: Jesus in the other verse majors on the choices that result from grace.”

That’s confusing to me.

It seems if you choose to see things that way, then you’re either chosen for heaven or you’re not chosen, and it doesn’t matter what the hell you believe or do.

Oh, well. Probably not important.

But wait.

God wants *all* men to be saved (cf. John 3:17; 1 Timothy 2:4),

but He chooses *not* to save *most* men?

What the hell?

That, of course, is why Romans 9 needs careful exegesis… as does John 3 and 1 Tim, of course.

That’s also why Aquinas treated Ephesians 1 so carefully, and yet saw it as a good, not a difficulty, when he wrote:

Good Latin, Jon. It is much more better than mine.

Jon:

A quick note on Denton’s new book.

Whether his religious position has changed since his second book, *Nature’s Destiny*. is unclear to me. In that book he spoke of God with some frequency, not in a religious tone but in the mode of natural theology. He indicated that his book amounted to a revived argument for natural theology. There was nothing specifically Christian about his references to God, but he did seem to envision a personal being (or at any rate a being with a designing mind) who planned for the universe to “output” human life (or something very much like it) as a computer program outputs its results. (He actually uses that metaphor.) So his view in that book would seem to be at least Deistic, if not Theistic. And he does use the word “design” frequently in the book, especially in the conclusion. He thus gives all the impression of being an ID proponent.

In the new book, the word “God” is not prominent, and he speaks of ID people as people with views compatible with his, but seems to distinguish himself from them, not as doing anything against what they are doing, but as doing something somewhat different. He does talk about “design” now and then, but he seems more interested in showing that biological forms are immanent within nature, and he doesn’t actually claim that the “Types” are the product of intelligent design by any personal being. His book thus might be interpreted almost pantheistically — as if nature is the expression of the divine, rather than something designed and created by the divine. But it’s hard to tell, because he stays away from theological questions in the book, even more than he did in the second book.

It is possible that there has been no change in his views, and that the avoidance of “God” language was purely a rhetorical choice, in order to give the book the widest possible appeal to biologists (many of whom have an axe to grind against religion). Indeed, the new book does come across as a purely scientific discussion of two very different views of evolution, the Darwinian and the structuralist. So if that was his goal, he succeeded; but it wouldn’t follow that he denies a role for God in generating the “Types.”

As a Platonist I’m of course attracted to the idea of “Types” and I see them as a natural bridge between theological talk and scientific talk. The question is whether someone can take Denton’s scientific argument and run with it theologically. What would the doctrine of Creation look like, expressed in Dentonian evolutionary terms? This is something I want to think more about.

Eddie

I’ve got Nature’s Destiny, but had forgotten its religious stance in the four years since I’ve read it. As I said, I’ve not got round to the new one (too many band arrangements to do!), but I surmise that structuralism is more or less equally compatible with both Platonic and Aristotelian ideas of form.

If so, creation (taken overall) might not look that utterly different from the kind of thing Aquinas believed in his synthesis… allowing for a revised conception of change over time, of course. It would still involve the instantiation of an idea within the mind of God, just as do those things we already know to arise from “natural laws” in our world.

Edward,

“The question is whether someone can take Denton’s scientific argument and run with it theologically. What would the doctrine of Creation look like, expressed in Dentonian evolutionary terms?”

What does the “doctrine” of Creation” look like now (i.e. pre-Denton)?

Are you saying religious “doctrine” may change based on the opinions/conclusions of science?

Cath Olic:

If you want to know what the doctrine of Creation looks like, read the relevant passages of Augustine, Aquinas, Calvin, etc.

And no, I am not saying that the core religious doctrine needs to change. You know that. You were present on BioLogos when I took all kinds of lumps from commenters and management alike for arguing that BioLogos seemed to be departing from core Christian theology. So I cannot think that your question now is entirely sincere.

Doctrine does not need to change, but its formulation may change, as new intellectual categories become available. The early Church consisted of fishermen etc. who thought in a Semitic idiom, and who knew as much about Aristotle as a Kentucky hillbilly knows about quantum physics today. Later on, the Roman Church recognized the value of Aristotle for the formulation of Christian doctrine, to the point where Thomas Aquinas has become one of the most important doctors of the Roman Church. That represents a change in formulation of doctrine, but not in the core of doctrine.

Similarly, if we learn something new from scientific research about *how* God created, that may lead to a change in our expressions, but need not involve abandoning any required doctrine.

I am formerly from BioLogos. I no longer want anything to do with them due to their deistic/atheistic views. I was recommended to come here. I am a step-descendant of Catherine Tudor of Berain. My ancestor, Morris Wynne, was her third husband. Catherine’s great-grandfather was Henry Tudor, King of England and Earl of Richmond. I suppose the Richard III Society would not like me very much. I had an ancestral uncle by the name of Henry Wynns, whose name I used on BioLogos. I hope I am welcome. Henry

Hi Henry – welcome. I’ve seen your posts in my moonlighting over at BioLogos. You’re welcome even though one of my good friends was a champion for Richard III decades before they dug him up.

However, since we’re discussing credentials, it seems one of my distant ancestors was Elizabeth I’s Archbishop of Armagh, John Garvey, so we seem to have roots in the same dynasty. The fact that my more recent ancestors were iron-moulders in the Black Country and tended to die in pub brawls etc needn’t be mentioned…

I wish to thank you, Jon. I would like to go “home” to England one day. I suppose that is why I love my Virginia so. As you probably know, we are very English here. I am glad that the previous John served Elizabeth I. Perhaps that is why we are interested in many of the same things. I have a lot of reading to do here. It all looks very interesting. I still consider Wales to be part of England even though Great Britain’s government is more federalized now. My God bless us and our wonderful efforts. I wish to thank you for welcoming me.

Don’t let a Welshman hear you say Wales is part of England! That said, I love Wales and my brother even more so – he even took the trouble to learn Welsh.

Before I go for now, I like what you said. That is true. I do not think my Welsh kinsmen would not like that. They should remember, however, that the first Welsh King of England, Henry, did unite the two. If I ever come to Britain, I will keep in mind what you have said.

Hi, Henry. Glad to see you’ve found the site. Hope you will enjoy the discussions here.

Dang! now one of us will have to write something to discuss. Fancy doing a piece on how the windows of heaven evolved by natural selection…? 🙂

My dear friend,

I am already happy to be here with such fine scholars and lovers of our Lord Jesus. I thought you would like to know that a certain organization has suspended me to December 28, 2289. I told them to do that. Don’t worry, I said nothing else. I am enjoying what I am reading here. Now, I feel truly among the spiritually living. In 2289, I shall be in heaven. That is all I have to know. I find the articles here quite interesting. I also like the statement of faith. I have made a copy of it and placed it in my notebook of scholarly things. I hope no one mines. I really am impressed with the scholarly minds here. I always new you were a fine scholar. I wish to thank you for inviting me. I am now going to study a book in theology in German written by Joseph Ratzinger and then I shall watch “Jane Eyre” as well as a DVD about William Tyndale. I shall be popping in to read on the camel later sometime. May our Lord Jesus bless everyone here.

Hi, Henry.

Which version of Jane Eyre are you going to watch? I’m fond of the 1944 version starting Orson Welles and Joan Fontaine. If you can get a copy of the “Cinema Classics Collection” DVD put out by 20th C Fox Video (ca. 2007), it not only contains a good print of the movie but has a boatload of special features, including detailed commentaries on the film.

Hi, Eddie,

I like the Orson Wells version too; however, I watched today the George C. Scott version. I enjoy that one as well. Those were very good movies by great English writers of the early nineteenth century. I enjoy them. Have a good night. Henry

I wish to say something else. I am quite impressed with the people on this forum. I believe I do recognize some of the names here. Dr. Edward is a very intelligent person and I have enjoyed our conversations. I am a BA in German, History, and Philosophy at Old Dominion University and received my MAR from Liberty Baptist Theological Seminary. I am a conservative evangelical and a Southern Baptist. I could be in reference to eschatology an historic premillennialist in the tradition of George Eldon Ladd, an American Baptist and erstwhile professor at Fuller Theological Seminary. I also could believe like Anthony Hoekema, or William Hendriksen, both amillennialists. Ladd’s view and theirs are non-dispensationalist. Again, I hope I am welcome. God bless.

Henry,

I should respond that we have a different aim here to that of BioLogos: that of trying to bring all branches of knowledge on origins together under one roof – a roof that seeks to remain true to classical Christianity (see here for what I mean by that). They have always struck me as keener to wave the flag for the truth of a particular view of science against Young Earth Creationism, which eclipses the sometimes excellent stuff like that of Ted Davis, as a notable example.

For whatever reason, their discussion board seems to have become increasingly a talking shop for speculative theology, largely from heterodox sectarian sources. I’ve lost the patience to respond to much of it… as I would here, with the difference that I have occult powers to make it disappear!

I like that.

Dear Jon,

I must say that I like your statement on CPN. I have finally found where I belong. May God bless.

To Edward’s 16/03/2016 at 02:24 am,

“If you want to know what the doctrine of Creation looks like, read the relevant passages of Augustine, Aquinas, Calvin, etc.”

I won’t speak for Calvin, but I think I can for Augustine, Aquinas, and others, as formulated in Catholic Church creation doctrine. I’d say that this creation doctrine says, among other things, that

1) God brought the universe into existence, and more importantly,

2) God created the universe FOR MAN, as a gift “addressed to man.”

Related to this, I’ve been pondering some more about those Aquinas words (‘The WAY that God created the world reveals God’s character. A wrong understanding of the WAY that God created the world reflects a false understanding of God.’)

and about how Scripture always, I think, shows God by his word creating things *quickly*, even instantaneously.

And I wonder why God would have overseen an amazing (and deadly) world of inanimate and animate things for millions, even billions, of years *when the entire purpose of creation, namely, man*, wasn’t around to appreciate it and give God the glory.

For millions of years, even billions of years, all these living, suffering and dying things but zero in terms of the economy of salvation; no forward or even backward movement in terms of progress toward a perfection that only man is capable of achieving by grace.

No divine lessons to be learned.

For 13 billion years or so, essentially and theologically nothing.

Wow. I’m not sure what the above would say about God’s character.

To me, it would seem like a rich guy who builds an amazing ballpark, has the grass cut and the field meticulously manicured every day – for decades and decades. But in all that time, he never has, and *knows he’ll never have*, any players to step onto that field and *play the game.*

I’d call that guy quite a “character.”

Cath

The question of how man’s rule of the earth fits in is indeed a significant one that needs understanding, but is not unique to the question of deep time. Understanding it in that context actually helps clarify what Scripture teaches on man’s rule, avoiding both “Baconian” dominionism and the denial of human exceptionalism.

After all, in terms of magnitude the earth is just a blip in a vast universe, which, at least before the parousia, is for the most part entirely off limits to mankind. And that’s been known, in essence, since the middle ages. The atheists use it as a lever (the so-called Copernican principle) to say that mankind is insignificant.

But that doesn’t follow for all kinds of reasons, many or most of which were picked up by theologians in times past:

(a) Though the present earth is man’s domain, organised both to bless him and to allow him to bless it and express its worship, and the biblical record necessarily reflects that (since it too is to bless man and enable him to be a blessing), that does not mean that God has no other purposes in creation. For example, it was common even back in the 17th century for divines to assume that the heavenly bodies were all inhabited, mostly by superior and more perfect races. God similarly could have created the past ages for his own different purposes, and for their own sake: the Bible’s concern, however, is primarily our role, and so it is rightly anthropocentric.

(b) The universe needs to be that big for us to exist at the scale we do (cf Teller and cosmic fine-tuning) – the fact that a gram or two of radium comes from tonnes of pitchblende does not make the radium insignificant. Likewise a long period of existence before man says nothing about his significance, especially if God, in his wisdom, made that a necessity.

(c) The rule of nature includes – more fundamentally than is recognised – the offering of rational worship on behalf of the irrational creatures for their goodness. And that is just as possible for a long-extinct, but “reconstructed”, dinosaur as it is for a lion.

(d) Another major part of man’s role (fulfilled in Christ) is the transformation of the cosmos from the physically-empowered to the spiritually empowered, which Scripture represents as the good being changed for the better, not the evil being transformed to good, so that God is all in all. To say that any particular period of time is “too long” for the old creation is a purely subjective value-judgement. God’s timing is his own concern.

(e) The “red in tooth and claw” idea of the world expressed in your word “deadly” is to me one of the most unfortunate developments in theology (adopted with relish by the Darwinians) after the middle ages. It is not the way the Bible describes the good creation even now, after man’s fall, and much less how one should accurately characterise the world of deep time before sin. I’ve written a number of posts on the anti-creation bias shown by such ideas here, whether used by evolutionists trying to say that evil predates the fall, or Creationists denying deep time because evil couldn’t predate the fall – both have a pessimistic and pre-Christian view of nature that dates only from the time of the Reformation.

Finally – as a general thought – some of my main beefs against theistic evolutionists have been when they reason along the lines of a “any God worth his salt wouldn’t have done it that way.” Because if it turns out he did do it that way, and ones watertight reasoning was wrong, ones empty blasphemy has achieved only condemnation for oneself.

Cath Olic:

Does the Catholic Church teach that the Creation was *only* for man? Not also for the sake of other creatures? Not also for the sake of God?

Also, please give the exact source for your Aquinas quotation. (You used quotation marks, so I assume you were giving a quotation and not a paraphrase. But even if it’s a paraphrase, please give the source for the claim.)

Finally, I don’t think God created Israel or the Church instantaneously. He brought them into being by means of lengthy preparatory processes (the captivity in Egypt and Exodus, the three-year teaching mission of Jesus and all the prior history of Israel which set things up for the coming of Jesus). Fine things may take time. And of course, since God dwells in eternity, not time, he does not have to “wait” for billions of wasted years for products of evolution to emerge. Man is as present to God in his eternity as the first bacterium is. It is only perishable things that feel the passage of time, not God. So your concern about long years of waiting seems misplaced, and based on an unduly anthropomorphic conception of God.

Interesting examples, Eddie – both Israel and “a people not yet created” (ie the Church, in NT speech) are described by the verb “bara” (create) in the Hebrew Scriptures.

I still suggest that ex nihilo is part of the content of creation (bara), but not necessarily as regards the material (maybe it is applied to what we might now call “information”, “form” or whatever else is new and divine in the act of creation.)

Otherewise we’d have to say that, taking Genesis 2 at face value, Adam wasn’t created because he was formed from dust (and from a subsequent inbreathing by God).

Edward,

“Does the Catholic Church teach that the Creation was *only* for man?”

It certainly appears that way.

For example, from the CCC’s #299:

“… The universe, created in and by the eternal Word, the “image of the invisible God”, is *destined for and addressed to man*, himself created in the “image of God” and called to a personal relationship with God.”

………….

“Also, please give the exact source for your Aquinas quotation.”

I have only what I showed.

But even if the quote was bogus, it raises a worthy topic. Since God is so interested in his revelation, in revealing himself through his words and his ways, wouldn’t the WAY he created reveal something about him?

…………..

“Finally, I don’t think God created Israel or the Church instantaneously.”

Neither do I.

I didn’t say God creates all things instantaneously.

I said Scripture always, I think, shows God by his word creating things QUICKLY, even instantaneously.

The Church says it was created at Pentecost. Pentecost was pretty quick, I think.

Secondly, the “creation” of Israel or of the Church is not “creation” as the word is formally understood. Their formation was substantially different from making something from nothing or making a man from mud. Their formation was more akin to change in, and/or growth of, certain existing peoples.

…………….

“He brought them into being by means of lengthy preparatory processes… Fine things may take time.”

Like fine wines. But not always (cf. John 2:9-10).

……………

“And of course, since God dwells in eternity, not time, he does not have to “wait” for billions of wasted years… It is only perishable things that feel the passage of time, not God. So your concern about long years of waiting seems misplaced, and based on an unduly anthropomorphic conception of God.”

Here’s just one of many verses about God “waiting” –

“So Moses and Aaron went in to Pharaoh, and said to him, “Thus says the LORD, the God of the Hebrews, `How long will you refuse to humble yourself before me? Let my people go, that they may serve me.” Exodus 10:3.

Were Moses an Aaron unduly anthropomorphic here?

Cath Olic:

It’s pretty irresponsible of you to quote “Aquinas” without checking the source yourself.

Obviously Moses and Aaron are speaking to Pharaoh in the language of men, the language that he understands. In that language, “how long” is a perfectly reasonable question. For God, the length of time is irrelevant. He knows the outcome; he’s not in suspense; Pharaoh isn’t holding God up. What Pharaoh is holding up is the inevitable sequence of temporal events, including Israel’s escape from Egypt. Any good Catholic teacher could explain this to you. Why don’t you go to a Catholic college and do some studying, instead of trying to teach the stuff to yourself?

Pentecost may have been quick, but how did all those follower of Jesus come to be there for that quick event? There were several years of work involved in assembling them.

There are no statements in Genesis indicating how long it took God to make sea creatures, etc. (Of course if you want to join the Protestant fundamentalists and say “one day” — you are welcome to; but who reads the “days” literally any longer? Certainly not a single one of the authors of the current Catechism of the Catholic Church, I assure you.)

Finally, I don’t see the word “only” or “alone” in the passage you cite in the CCC regarding the purpose of Creation. And the CCC is hardly the only Catholic document in the world. What others have you consulted? If it has “always and everywhere” been the teaching of “the catholic church” that creation was designed exclusively for man, you should have *no problem* finding me lots of passages which say so in various Catholic theological writings and official documents.

I must agree with your statement here. It is unimportant how long took to create. Time is for us and not for God, even though He could enter it through His Eternal Son, Jesus.

“The way God created …….”

I have a lot of time for Thomas, and I think that if we try and understand the latest advances in the Sciences, we may obtain a glimpse in the way of the Creation – I wish these discussions would include the obvious notion that God is not limited by space and time. If we try to understand this, than the Gospel can be better understood, in that God created the “instant” He uttered (or the Word commanded), and it includes all past, present and future that we try to comprehend. This removes the notion of ideas in God’s head (gives me a headache thinking like that), and speaks absolutely of God’s Sovereignty over all creation.

On the time we humans need to contend with, it may help us to realise that salvation of us wayward beings takes a great deal of effort by Christ – this is hard work by any reckoning – but we mess understanding even this part of the revealed Gospel(!).

Hi GD

Yup – I think Aquinas followed Augustine in concluding that God, in eternity, creates all things – from beginning to end – in one simple act. Augustine’s problem was that God should take as long as seven days, and concluded it (or the description of it in such terms) was accommodated to human temporal understanding.

This seems, in principle, to solve all problems about the time take, for things to happen within creation. But it also undermines the deist, or semi-deist assumption one sees so much in these discussions about God creating the universe “at the beginning” and then “letting it unfold” under its own steam: this implies that God was only creatively active at one instant in history, which is absurd… as you’ll appreciate, from the Orthodox perspective, God’s sustaining of all things being closely related, at least, to creation.

To Jon’s 16/03/2016 at 08:44 am,

“… that does not mean that God has no other purposes in creation. For example, it was common even back in the 17th century for divines to assume that the heavenly bodies were all inhabited, mostly by superior and more perfect races. God similarly could have created the past ages for his own different purposes, and for their own sake…”

We weren’t so much talking about opinions or about 17th century assumptions.

We were talking about creation *doctrine.*

The creation *doctrine* I’m aware of says all of God’s creative activities were directed toward man.

“Another major part of man’s role (fulfilled in Christ) is the transformation of the cosmos from the physically-empowered to the spiritually empowered, which Scripture represents as the good being changed for the better, not the evil being transformed to good, so that God is all in all. To say that any particular period of time is “too long” for the old creation is a purely subjective value-judgement. God’s timing is his own concern.”

Yes, the timing is absolutely God’s concern, and his prerogative.

And related to that, we can say that *time* and *timing* are important to God.

We also know – or at least the doctrine of some is – that creation is ordered for man. So, I continue to wonder why a God so concerned with time and with man would allow 13 billion years of time to go by with no man (and no ‘spiritual empowerment’, no good becoming better).

“The “red in tooth and claw” idea of the world expressed in your word “deadly” is to me one of the most unfortunate developments in theology (adopted with relish by the Darwinians) after the middle ages. It is not the way the Bible describes the good creation even now, after man’s fall…”

Should we dispense with Romans 8:22-23 – “We know that the whole creation has been groaning in travail together until now”?

Was it an unfortunate development of theology, a slip of the tongue?

What words besides “groaning” and “travail” should Paul have used?

Cath Olic:

1. “Red in tooth and claw” is quite a different image from “groaneth in travail.”

2. You object to Jon’s citing “divines” and claim that instead you want “doctrine”. What do you think divines talk about? Baseball? They talk about doctrine. That’s what they study. That’s what they teach. But I suspect you mean “doctrine” in a narrower sense than is commonly used. Given your usual agenda, by “doctrine” you likely mean “what the Church of Rome teaches.” But of course, that begs the question whether what the Church of Rome teaches is true doctrine. In some cases, it is. In other cases, it isn’t. And since Jon has asked us not to debate the truth or falsehood of Roman Catholicism, I won’t say anything further than that.

3. “So, I continue to wonder why a God so concerned with time and with man would allow 13 billion years of time to go by with no man (and no ‘spiritual empowerment’, no good becoming better).”

The proper response is that God is not really concerned with what you wonder about, but follows his own counsels; and that whether he chose to allow 13 billion years or 13 seconds before the appearance of man is entirely his own business. Indeed, Augustine answered a similar question centuries ago, when someone asked what God was doing for all the millions of years before he created the world. You probably already know Augustine’s scathing reply, but if you don’t, I’m sure that with your knowledge of Catholic theology you will be able to quickly find it. The point, of course, is that some kinds of theological wondering are non-constructive because they are offered with combative intent rather than in the spirit of faith seeking understanding.

Hello, Eddie.

I am not sure that I should join in on this point; however, since we are still living in time, perhaps I should try to contribute something. If I do not make the mark, I hope you and the others will excuse me. It is a difficult discussion to determine what was happening in eternity. In my opinion, something must have been going on in what I shall call eternity past. I feel that the angels and other heavenly beings that God created have been around much longer than our existence. I also wonder what actually happens when we die as Christians. It could be that there is an eternal soul that lives separately in the intermediate heaven ruling with Christ in His millennial reign. I am now approaching this from an amillennial or postmillennial view. It also could be since time and eternity are not the same, that we step out of time at death and walk into eternity. What does this mean? The dead in Christ might experience the Second Advent and the return of Christ even though believers on earth are at the graveside in time. This does not mean that Jesus will not reenter time one day with the Second Advent; on the contrary, for those who already are in eternity, they might experience it when they leave this life. You are probably asking what does this have to do with what I will call eternity past. Perhaps this might be a logical answer to that question. I hope so. Perhaps God has always seen eternity and time. There has never been a period when he did not. Is that rather Calvinistic? Perhaps. I must say that this discussion is really exercising my old noodle. It is the same with us. How many times have we lived this moment? For us, it is the first time. But in the Mind of God, it has happened many times. Therefore, my humble answer to our Catholic friend is this: Even though there is a creation for us, God has in eternity always experienced what has been, what is, and what shall be. It hope this makes logical sense to everyone. It is rather late now; therefore, I must drink some soda and go to bed. God bless.

Hi, Eddie

Does my statement below have any relevance to the conversation here? I would just like your opinion. Take care.

Hi, Henry.

The way this page is laid out, with nested replies, both of your statements are “above” rather than “below.” Are you referring to your longer or your shorter statement? Your shorter statement I agree with; it more or less makes the same point I was making. Your longer statement I can’t completely follow, because it seems to cover more than one subject or make more than one point. But you mentioned angels. I would ask you: are angels in the realm of time, or of eternity? I assume that they are in the world of time, because they are created beings, but if I am wrong then Jon or someone will hopefully set me straight. Anyhow, if they are in the realm of time, and if they were created before man was, then yes, they would have been doing something before the creation of man — but not before creation overall. Before creation overall — and even using the word “before” is tricky there — there were no angels doing anything, and there was no duration of time. There was only God, alone, in his eternity. That’s how I understand the typical Christian doctrine.

I believe that you are correct now that I think about it. Perhaps it was thinking of the concept of how we as Christians get to heaven at the moment of death as well as the Second Coming and applying that to angels. The traditional view of the human soul leaving the body at death to go to heaven would imply that they are still within another level of time. If Congregationist W.D. Davies, a former professor of New Testament at Duke Divinity School, was correct that we step into God’s eternal now when we leave this life, then that might imply that angels are outside of time too. I will have to think about that. No, the thought is clear to me now. I do have trouble with Davies view. The spirit of Samuel in I Samuel 28 appearing to King Saul without his body would imply time. Therefore, I would have to say that angels are within time, and therefore were not in God’s pre-creation eternity. I do believe you are correct, my friend. I have enjoyed our conversation today. I helped me to get some cobwebs out of the old noodle.

I meant: It helped me to get some cobwebs out of the old noodle. I believe I need a new keyboard.

Eddie

Eternity for created beings is an area I fear to tread … maybe the angels do too.

Of late I’m thinking that “eternal life” (as per the future hope) should not be taken “technically” as entailing timelessness. remember the Christian hope, biblically speaking, is resurrection to bodily life that’s imperishable, with the rest of creation – which doesn’t seem to sit well with sharing God’s timelessness, which seems to me to be one reason for his unique omniscience and omnipotence.

On the other hand one might wonder how we will see God “face to face” if he is in eternity and we in time.

The intermediate hope is being in the presence of Christ in heaven, but awaiting resurrection on the new earth… “waiting” seems to imply passage of time.

So there are some factors: since, as far as I’m aware, the time-frame of the age to come has not been revealed, I shall attempt to follow Calvin’s dictum of not going beyond what is written.

I also agree with your conclusion now. It accept now that our spirits go to the intermediate heaven until the resurrection on the new earth. It fits better with the Holy Scriptures. Also, I agree now with RVG Tasker, late professor of New Testament at the University of London, that II Corinthians 5:1-10 mostly talks about the intermediate state. What the Apostle Paul meant to Tasker and now to me in II Corinthians 5:1 is that we have a home in heaven until the resurrection of the body and the renovation creating the new earth. Tasker compares the house in the heavens with John 14:1-3. I think Rev. Tasker was right and he does know the exact answer now. The house in the heavens is what Jesus meant when he said: In my Father’s house are many mansions. The mansions or dwellings are our house in the heavens. If I felt better, I would work on a BD online from the University of London. The United Kingdom BD seems to be the same as our MDiv in North America. Thank you both for sharing your knowledge. God bless.

To Edward 17/03/2016 at 02:23 am,

“Obviously Moses and Aaron are speaking to Pharaoh in the language of men, the language that he understands. In that language, “how long” is a perfectly reasonable question. For God, the length of time is irrelevant. He knows the outcome; he’s not in suspense; Pharaoh isn’t holding God up. What Pharaoh is holding up is the inevitable sequence of temporal events, including Israel’s escape from Egypt. Any good Catholic teacher could explain this to you. Why don’t you go to a Catholic college and do some studying, instead of trying to teach the stuff to yourself?”

One reason I don’t you go to a Catholic college to have them explain this stuff to me is that, if they’re anything like you on the above, they wouldn’t be teaching me anything I didn’t already know.

Another reason is that they, like you on the above, may mix in sloppy and theologically problematic propositions, like “For God, the length of time is irrelevant.”

……………

“Pentecost may have been quick, but how did all those follower of Jesus come to be there for that quick event? There were several years of work involved in assembling them.”

But a lot fewer than 13 billion years of work.

More importantly, the years of work that *were* involved in assembling them comprised *Divine-to-human and human-to-human* interactions.

And in terms of the salvific *progress* of those interactions, for God, *sooner is generally better than later*…

“Philip said to him, “Lord, show us the Father, and we shall be satisfied.”

Jesus said to him, “Have I been with you so long, and yet you do not know me, Philip? He who has seen me has seen the Father; how can you say, `Show us the Father’?”

……………….

“If it has “always and everywhere” been the teaching of “the catholic church” that creation was designed exclusively for man, you should have *no problem* finding me lots of passages which say so in various Catholic theological writings and official documents.”

You’re right, it should be *no problem.* But it sure could take up a lot of time and space.

It would be much better if *you* present for me just one or two pieces of Catholic *doctrine* – for we *are* talking about doctrine – which effectively say creation was NOT destined for and addressed to man. (I haven’t found such. Maybe you can.)

Cath Olic:

I realize that, given your tendency to ecclesiolatry, the Bible may not count as a source of “doctrine,” but have you ever read the book of Job? Are you not aware of the statements there in which God indicates that not only man, but other creatures, are his concern in the plan of creation?

I find it amusing that you rest so much weight on the Catechism of the Catholic Church, given your apparent contempt for virtually all Catholic Church officials and theologians. You won’t take courses from them (because you know Catholic theology far better than they do), and you are always bad-mouthing them for their liberalism; yet you assume that suddenly, when they get together to write up the Catechism (which in its current form is largely a committee production of clergy and theologians trained in the post-Vatican II era, i.e., in the most liberal era in the Church’s history), all their intellectual and spiritual defects will vanish and they will write up a perfect Catechism which you can rest in with 100% confidence.

And I suppose that if I showed you statements of Augustine and Aquinas which clearly contradicted the passage you’ve pulled out of the Catechism, you would just dismiss the statements, as the purely private opinions of Augustine and Aquinas, which cannot be set against “doctrine.” So what is the point of my digging up historical sources to show that your Catechism statement is inadequate, or at least is not the whole story? You will just dismiss the sources you don’t like.

To Edward’s 17/03/2016 at 02:42 am,

“You object to Jon’s citing “divines” and claim that instead you want “doctrine”. What do you think divines talk about? Baseball? They talk about doctrine. That’s what they study. That’s what they teach. But I suspect you mean “doctrine” in a narrower sense than is commonly used.”

Yes, I mean in a narrower sense. I mean *doctrine*, not talk *about* doctrine.

Anyone can talk about doctrine. But I’m not interested in just anything anyone says *about* doctrine.

I thought you were, too [“If you want to know what the *doctrine* of Creation looks like, read *the relevant passages* of *Augustine*, *Aquinas*, *Calvin*…” (i.e. not any old “divine”)]

…………

“Given your usual agenda, by “doctrine” you likely mean “what the Church of Rome teaches.” But of course, that begs the question whether what the Church of Rome teaches is true doctrine. In some cases, it is. In other cases, it isn’t.”

Well, at least you believe in infallibility. Yours.

…………….

“…whether he chose to allow 13 billion years or 13 seconds before the appearance of man is entirely his own business.”

Quite true.

“Indeed, Augustine answered a similar question centuries ago, when someone asked what God was doing for all the millions of years before he created the world. You probably already know Augustine’s scathing reply, but if you don’t…”

As God is my witness, I don’t.

But I would say that before God created the world, *there were no years* for him to do anything, because time had not yet been created.

I’d say further that

1) God created time (i.e. a measure of change), but

2) God is outside of and apart from time – just as he is separate from all of his creations, but

3) God can and does operate on and within his creation, which obviously includes time.

And also, that once God *does* create a “game” involving matter, men, and *time*, none of them is “irrelevant” to him.

To Edward’s 17/03/2016 at 04:57 am,

“… have you ever read the book of Job? Are you not aware of the statements there in which God indicates that not only man, but other creatures, are his concern in the plan of creation?”

Indeed.

But why not get more up-to-date, with THE Man himself?

Jesus said “Are not two sparrows sold for a penny? And not one of them will fall to the ground without your Father’s will.”

But of course, he followed that with

“Fear not, therefore; you are of more value than many sparrows.”

…………

“And I suppose that if I showed you statements of Augustine and Aquinas which clearly contradicted the passage you’ve pulled out of the Catechism, you would just dismiss the statements, as the purely private opinions of Augustine and Aquinas, which cannot be set against “doctrine.””

Kind of like, on a separate topic, Augustine’s flirting with the idea of “delayed ensoulment” of the life in the womb?

Yes, I would dismiss it.

Edward had earlier mentioned Calvin, regarding Creation doctrine.

Just out of curiosity, tonight I briefly Googled to find out a little about John Calvin’s creation “doctrine”.

Apparently, he believed in a literal, six 24-hour days creation.

*But more importantly*, regarding the subject at hand, I read:

“For Calvin, God’s creation was intrinsically good and behind the creation of the world there was a divine order and purpose. In the very beginning, *the world was created to serve man.*

This, for Calvin, *is the whole purpose of God in his creation*…

This same idea is brought out in the Institutes where Calvin says:

‘God himself has shown by the order of Creation the *he created all things for man’s sake*.’”

http://archive.churchsociety.org/churchman/documents/Cman_105_2_Hallett.pdf

Quite Catholic! I mean, quite orthodox.

Cath Olic:

“Quite Catholic. I mean, quite orthodox.”

“Quite un-Biblical” is the phrase that comes to my mind. It’s certainly not the teaching of either Genesis or Job.

Apparently you think I am wedded to the all the words of Calvin. But while I agree with Calvin on some matters, e.g., the matters on which he disagrees with BioLogos, I don’t give him an automatic pass on everything. I don’t give any theologian an automatic pass on everything. If they start adding to or subtracting from the Bible in the interest of their own agenda, I raise objections. Calvin’s statement goes beyond what the Bible says, and even beyond what can be safely inferred from what the Bible says. So I don’t regard it as authoritative.

If you want a discussion of the history of anthropocentric vs. non-anthropocentric readings of creation within Christian theology, I recommend Santmire’s book, The Travail of Nature . It wisely avoids the usual Catholic vs. Protestant polemics, and shows how *both* Catholics *and* Protestants have divided over the question of anthropocentrism. One can certainly find unwarranted, un-Biblical anthropocentrism in Catholic as well as Protestant doctrine; but one can also find both Catholic and Protestant authors who have seen non-anthropocentric themes in the Bible.

For example, the fact that we are worth more than sparrows does not mean that sparrows are worth nothing. The story teaches us that sparrows are one of God’s concerns in creation. Creation benefits them; they enjoy it; in their own non-rational way they perceive the glory of God through it. And the ultimate purpose of Creation is not to serve man, but to express the glory of God — I believe that the Presbyterian catechism used to begin with that. You will find similar statements in Aquinas. Creation benefits man, but it is not exclusively or even primarily for man. It is for the glory of God.

On one of your other points, time is “relevant” to God in the sense that God ordained a world which would operate in time, but God does not feel the passage of time. He does not have to “wait”; he is not impatient, drumming his fingers waiting for Pharaoh to comply. He has no emotional stake in how long Pharaoh takes to come around. That Pharaoh will eventually come around is guaranteed. God’s plan to liberate Israel cannot be thwarted. And it’s a matter of emotional indifference to God whether the earth will be ready for man in 6 days or 14 billion years. He isn’t going to have any sensation of long, wasted years without man. Man’s arrival is guaranteed and is present to God as fulfilled. It is only the creaturely world of reptiles and birds and mammals etc. which could possibly groan with impatience: “Gee, how many more million years do we have to wait before man comes along to rule us?” God doesn’t experience things in that way.

Edward,

“Apparently you think I am wedded to the all the words of Calvin.”

No, I didn’t assume that.

However, I suppose I DID assume that you considered creation doctrine to include what Calvin said about creation [“If you want to know what the doctrine of Creation looks like, read the relevant passages of Augustine, Aquinas, Calvin, etc.”]

And at least part of Calvin’s creation doctrine says that creation was *made for man*.

But I guess all creation *doctrine* isn’t created equal.

John Calvin’s certainly isn’t the same as Edward Robinson’s. Maybe you should have told me: ‘If you want to know what the doctrine of Creation looks like, ask me!’

………………

“If they start adding to or subtracting from the Bible in the interest of their own agenda, I raise objections.”

But I’d bet you didn’t object to your bible having only 66 books instead of 72.

……………..

“The story teaches us that sparrows are one of God’s concerns in creation. Creation benefits them; they enjoy it; in their own non-rational way they perceive the glory of God through it. And the ultimate purpose of Creation is not to serve man, but to express the glory of God…Creation benefits man, but it is not exclusively or even primarily for man. It is for the glory of God.”

Amen, amen. In the beginning, er, before the beginning, the Trinity was getting bored with each other, and was feeling down, low in self-esteem.

So the Trinity created the man-less universe as a pick me up, a pat on the back.

Glory to me! And thus, they felt better about themselves.

But the Trinity felt better still when those sparrows chirped their praise, on Sundays and Wednesdays (I think they’re Baptist).

And the trees that they nest in join limbs for an acapella chorus of praise, but on Saturdays (LDS, I think.).

(By the way, do ALL sparrows go to heaven when they die, to behold the eternal Beatific vision they’ve long desired? Or just some?)

Why, when you think about, the final addition of praise-capable men was quite anticlimactic.

Giving glory to God was doing fine without us.

…………

“On one of your other points, time is “relevant” to God in the sense that…”

Lord, thank you for not leading me to theology school.

I will try to spend the saved tuition money wisely,

and for your glory.

Cath Olic:

What I had in mind in referring you to Calvin, Augustine, Aquinas etc. was that you should read broadly in the great minds of the Christian tradition on the subject of Creation. I was not endorsing every single statement you might find in any particular figure. I don’t believe anyone has things entirely right. That is is why it’s good that we have a long and rich tradition of great thinkers, who can supplement and correct each other.

I think that most of what Calvin says about Creation will be in tune with most of what Augustine says, and so on. They will of course have differences over detail, e.g., Augustine thought that Creation was instantaneous, not spread out over time. But in broad outline they will agree that Creation involves both God’s will and God’s reason, that God is not thwarted by any inherent defects in matter, that God’s will is completely realized, that God does not leave Creation to randomness or chance, that God is not surprised by what Creation produces, etc. They will also agree that man is in a sense the crown of creation. I don’t believe, however, that all the Fathers will agree with Calvin’s statement that man is the only purpose of creation. I think you will find that perhaps Origen leans that way, but that Irenaeus and Augustine qualify the notion along the lines I have suggested. For more information, the book I suggested should give you a start on the sources.

Regarding the number of books in the Bible, I have not made any comment on the status of the Old Testament Apocrypha — most of the books of which are found in Catholic Bibles. The tradition in which I was raised, while not regarding those books as divine revelation, gives them a kind of secondary authority; they cannot be used to determine any doctrine, but are sometimes included in the daily Scripture readings. Years ago, in a service I attended, the minister read from the book of Wisdom. I have no distaste for those books. I own some Bibles which contain the Protestant books with the Apocrypha included at the back, as a lengthy appendix. I approve of that addition, as the material in the additional books provides background for the understanding of the New Testament.

Regarding the general tone of your reply, I will say that there is a witty sort of sarcasm, and a sort of sarcasm that is merely aggressive. Unfortunately, it seems you can manage only the latter. You might think about how such a bedside manner is likely to affect your attempts to convert people on the internet to your brand of Catholicism. People tend to judge the various forms of Christianity by their representatives. They assume that the spirit of a religion will show through in the behavior of its adherents. You might want to bear that in mind as you ask yourself the question: “Am I getting through to people?” That is, presuming you care whether or not you are getting through to people.

“The opinion of those who say with regard to the truth of faith that it is a matter of complete indifference what one thinks about creation, provided one has a true interpretation of God… is notoriously false. For an error about creation is reflected in a false opinion about God.”

– St. Thomas Aquinas, from Summa Contra Gentiles, II, 3,

as quoted by Joseph Pieper.

https://books.google.com/books?id=4h5vBQAAQBAJ&pg=PA133&lpg=PA133&dq=%22notoriously+false.+For+an+error+about+creation+is+reflected+in+a+false+opinion+about+God%22&source=bl&ots=2c1Hq3YEuC&sig=-GAVgknBBghG_Z-GVYMOFv3ejJI&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjmvLX5w8nLAhXFNSYKHbkHChMQ6AEIHDAA#v=onepage&q=%22notoriously%20false.%20For%20an%20error%20about%20creation%20is%20reflected%20in%20a%20false%20opinion%20about%20God%22&f=false

Cath Olic:

The quotation from Aquinas has no application to anything I have defended. I have not said that “it is a matter of complete indifference what one thinks about creation, provided one has a true interpretation of God.” Nor could you possibly think I have said this, if you have been paying attention to all my arguments with the TEs on BioLogos. I have said that it very much matters *how* God is involved in “evolutionary creation” — if evolutionary creation is to qualify as orthodox Christian doctrine. And I have been rebuffed by BioLogos leaders every time I have said it. I have been told that I am asking an unreasonable question and that no TE/EC should have to specify how God is involved in evolutionary creation.

I know that, in your love of black and white positions, you find it hard to “do nuance,” but maybe you can grasp and even accept this distinction:

There are some theological beliefs about creation which are central to Christian faith; there are others which are not.

We should insist on the theological beliefs which are central to Christian faith. We should not insist on the theological beliefs which are not. We should regard the latter as speculative possibilities which Christians may debate, provisionally accept, provisionally reject, etc.

I have already given, above, a list of central statements of Christian doctrine on Creation. Here is a list (by no means exhaustive) of statements that are *not* central to Christian Creation doctrine:

1. The world was created in six 24-hour days.

2. Genesis 1 gives a literally accurate account of how the world is created.

3. Macroevolution never happened; God created all living creatures directly.

4. The world is only about 6,000 years old.

5. Genesis 2-3 gives a literally accurate account of how man and woman and animals were created, of a talking serpent, of actual physical trees with fruits conveying life and knowledge, etc.

All of the above statements, and many other statements, are not central parts of Christian creation doctrine, and therefore can be debated and discussed freely and with open minds, with faith not hanging in the balance on the outcome of the discussions.

On the non-binding character of the propositions listed above, I would venture to say that the vast majority of living Catholic theologians agree with me, including those Catholic theologians who put together the most recent versions of the Catechism of the Catholic Church. I would venture to say that the current Pope agrees with me as well. But of course I stand ready to be corrected, by direct statements of the Holy Father, or of any of the Catholic theologians who were responsible for the Catechism.

Much has transpired here. A review is in order. I’ll title this:

“What I’ve learned from the above dialectics with the doctor (PhD)”

1)

“Doctrine” has no necessary relationship with truth, but means only the teaching of an *opinion* of what the truth is.

This is evident in considering two things from the doctor:

a) “If you want to know what the doctrine of Creation looks like, read the relevant passages of Augustine, Aquinas, Calvin, etc.”, and

b) His recognition that Augustine’s creation doctrine doesn’t equal Aquinas’ which doesn’t equal Calvin’s, etc.

2)

TRUE doctrine, on the other hand, is what the doctor determines.

3)

Closely related to 2) above, is the doctor’s belief in infallibility.

He doesn’t believe in the Catholic Church’s infallibility, of course,

but rather he believes in his own infallibility.

This is evident in his statement:

“… the question whether what the Church of Rome teaches is true doctrine. In some cases, it is. In other cases, it isn’t.”

4)

Although he acknowledges that God cares for his creation, and that his creation includes “time”, he believes

“For God, the length of time is irrelevant.”

He believes “God does not feel the passage of time…he is not impatient”.

[

Perhaps he will later explain God’s apparent impatience in Scripture (e.g. Exodus 16:28; Numbers 14:11; Psalm 4:2; Mat 17:17; John 14:9)]

5)

The doctor is primarily interested in broad reading and in dialectics, not in truth.

Or, at the least, he believes that after thousands of years of broad readings and a wealth of writings and interminable dialectics, no one has a full doctrine of creation which is fully true.

This is evident in the doctor’s statement:

“What I had in mind in referring you to Calvin, Augustine, Aquinas etc. was that you should read broadly in the great minds of the Christian tradition on the subject of Creation. I was not endorsing every single statement you might find in any particular figure. I don’t believe anyone has things entirely right.”

He gives the appearance of encouraging, and even valuing, correction –

“That is is why it’s good that we have a long and rich tradition of great thinkers, who can supplement and correct each other” –

but can’t answer who it is who is in the position to correct others, and why. No “why”, other than his opinion, or a consensus of opinions he happens to agrees with. This sits well with him, I suppose, because of 3) above.

6)

He agrees with Calvin and the Church Fathers and the Catholic Church, among others, that “man is in a sense the crown of creation.”

But he disagrees with their position that creation was “destined for and addressed to man” or that “the world was created to serve man” or that “God created all things for man’s sake.”

While he has mentioned some Fathers’ names, he has so far provided no citations from the Fathers which support his disagreement.

7)

Related to and in support of 6) above, he has stated his belief that non-rational

creatures, such as sparrows, perceive the glory of God.

[However, he has not yet stated whether he believes the sparrows and other non-rational creatures, with enough proper perception of God’s glory, can go to heaven.]

8)

He believes I should go to a Catholic college and do some intensive (and I assume “properly” supervised) studying, so that I, too, may make statements like his.

………….

The above are the primary takeaways that came to mind so far.

Good night, all.

Cath Olic:

I ignore all the non-intellectual parts of your carping post immediately above this one. On the substantive points:

When you’ve done a proper scholarly study on the range of views held by the Fathers re anthropocentrism, let me know. Santmire’s book would be a good place to start, as it would guide you to some of the primary sources you would need for the task.

As for the rest, we’ve already discussed the problem with your obsessive need for a human theological authority which can settle things for you, so that you can live without doubt, puzzlement, or angst. I don’t have that obsessive need. That’s why I’m not a fundamentalist — either a fundamentalist Protestant or a fundamentalist Catholic.

Edward,

“I find it amusing that you rest so much weight on the Catechism of the Catholic Church, given your apparent contempt for virtually all Catholic Church officials and theologians… and you are always bad-mouthing them for their liberalism; yet you assume that suddenly, when they get together to write up the Catechism (which in its current form is largely a committee production of clergy and theologians trained in the post-Vatican II era, i.e., in the most liberal era in the Church’s history), all their intellectual and spiritual defects will vanish and they will write up a perfect Catechism which you can rest in with 100% confidence.”

You’re free to be amused.

Similarly, you might be amused that I believe in the validity and efficacy of sacraments *even when* received from a priest who is in the state of mortal sin. I don’t find Donatism amusing. Perhaps you do.

But back to that Catechism, where does it say anything that conflicts with any previous editions of the Catechism or with any traditional Catholic doctrine?

Edward,

“If you want *a discussion* of the history of anthropocentric vs. non-anthropocentric readings of creation within Christian theology, I recommend … When you’ve done a proper scholarly *study on the range of views* held by the Fathers re anthropocentrism, let me know. Santmire’s book would be a good place to start, as it would guide you to some of the primary sources you would need for the task.”

Primary sources I would need for WHAT task?

I know. Not the truth task.

Rather, the task of engaging in still more *discussion* on an ever wider *range of views.*

A task kind of like a Full-Employment Act for PhDs.

And so, the doctor provides confirmation of my 5) above.

…………

“…your obsessive need for a human theological authority which can settle things for you, so that you can live without doubt, puzzlement, or angst. I don’t have that obsessive need.”

I know. You have no need for the Church.

The church of Edward will do.

Cath Olic:

I don’t deny the need for the Church. But it’s not the job of the Church to provide the sort of certainty that is necessary to satisfy the chronically intellectually insecure. The kind of person who needs to cling to neo-Thomism as the absolutely complete, flawless, and irrefutable truth about Christian theology, or to the views of Ken Ham as the absolutely complete, flawless, and irrefutable truth about Christian theology, or to the views of Barth, etc., is looking for the wrong thing from the Church. The Church of course has a commitment to some basic theological principles, but the main job of the Church is to provide a living, loving community in which Christian life can be lived out. Within that community, intellectual disagreement is possible, as long as it isn’t on core beliefs. I’ve mapped out some core beliefs regarding creation, and I’ve suggested a number of beliefs held by particular Christians about Creation that *aren’t* core and needn’t be insisted upon. You’ve made no comment on either set of beliefs. Do you dispute any of them? If not, then what are you arguing about? And if so, which of them do you dispute?

The fact that almost every discussion with you ends up with your accusing me of low personal motives indicates a serious problem. In the end, you turn to *ad hominem* remarks. One of the reasons I’ve suggested that you pursue some Catholic education at the university level is that professors would drill that bad habit out of you. All the *ad hominem* parts of your essays would be marked up in bright red, to show you how not to argue.

My friend Dr. Edward,

I must agree with this statement. The Church is here to teach us about our Lord and how to properly live with one another. Naturally, there can be differences in theology; however, these should go outside of orthodoxy. I must disagree with American Baptist Church theologian Harry Emerson Fosdick because his theology was heresy. He denied many beliefs of the Church including the literal Second Advent of our Lord. He only taught the immortality of the soul and denied the resurrection of the body, a concept clearly taught in our Holy Scripture. Our souls and bodies will clearly be reunited when our Lord literally returns to establish heaven on the new earth.

These should not go outside orthodoxy.

To Edward’s 19/03/2016 at 09:03 am – Part 1 of 3:

March Madness continues!

“I’ve mapped out some core beliefs regarding creation, and I’ve suggested a number of beliefs held by particular Christians about Creation that *aren’t* core and needn’t be insisted upon. You’ve made no comment on either set of beliefs. Do you dispute any of them?”

I think I may.

Firstly, I would say one of the core Christian beliefs about God *in general*, that is, *not* about any of his *actions in particular*, is his “omni-ence”:

he’s omnipotent, omnipresent, omniscient.

That omniscience includes the characteristic that he’s *not surprised* by *anything*.

Among what you say are core beliefs about creation is

a) “that God is not thwarted by any inherent defects in matter.”

This seems to presuppose that God *created* matter, including man, *with inherent defects.*

That’s not core to me, nor to the CC, nor to many other Christians.

b) “that God does not leave Creation to randomness or chance.”

Just a question here. Have you told those Christians at Biologos, and other TE/CE-ers, who hold to randomness/chance in evolution, that *they are violating* core Christian doctrine regards creation?

c) “that God is not surprised by what Creation produces.”

Now, I already said Christians believe God is not surprised by *anything*.