A few days ago I wrote about the claim that Scripture is “underdetermined” even about a central Christian doctrine like providence, a doctrine on which depends not only the nature of Creation, God’s government of human history and his promises for the future, but even the fundamental practical matter of prayer. I criticised the tendency of even highly-trained academics to cherry-pick Scripture references (and the erroneous “even-handed” suggestion that for every text for a particular position, there are others against). As the old Reformers used to insist, what matters is the whole counsel of God in Scripture.

That, of course, becomes a fruitless quest once one abandons the principle of Scriptural infallibility, for what is left then is a necessarily subjective search for tiny nuggets of God’s counsel in a contaminated human ore. How deep this selectivity goes appears from Peter Enns’ assertion, some years ago now, that Jesus’s way of interpreting the Old Testament is poor, a product of his 1st century Jewishness, which in turn is a conclusion from the assumption of self-emptying of God in the Incarnation of Christ. This goes far beyond the critical claim that most of Jesus’s sayings are spurious later additions: here the theological presumption is Jesus himself taught error. Presumably he taught some truth as well – but any objective criteria for separating gold from lode are lacking.

Lurking in such a theology is the questionable (or rather hubristic) assumption that critical academia has a better handle on divine truth than the Son of God. It’s a natural conclusion from the doctrine of divine kenosis, though, that if Jesus becomes truly like us (to the extent of making the same errors), then we in turn are truly his equals at least – and maybe better educated. But the theological paradigm of divine kenosis, paradoxically, is reached by assuming that Pauls’ teaching in Philippians 2.6ff is divine truth. That I would not, of course, deny, but I have argued elsewhere (here and here) that to interpret this passage as signifying any loss of the divine nature of Christ at the Incarnation is untenable.

That the very term kenosis, based on the Greek for “emptied himself” (or, better, “made himself nothing”) is found only in this passage referring to Christ, suggests that Philippians 2 is not only a proof text but the whole biblical foundation for kenotic theology. I’m not aware of seeing anyone, from Moltmann to the Open Theists or the Open Process Evolutionary Creationists, using any other biblical support for the idea.

Yet once adopted, kenosis invariably seems to proliferate to engulf the whole of theology, and even God himself. The usual logical path is to assume (wrongly) that Philippians 2 implies that the Son became less than fully God at the Incarnation (though Scripture says he took on flesh [Heb 2.14], rather than putting off deity, and the Church concluded at Chalcedon that neither his human nor divine nature were diminished). But having thus “established” that Christ’s love was an emptying of divine attributes, the argument goes that since we learn everything about God through Christ, the Father too must love through self-emptying.

And so to Moltmann, Creation is a lessening of God, literally (and rather crudely, it seems to me) to make room for others. To the open process guys, God gives up some of his freedom and sovereignty to give the secondary causes of nature autonomy. To Open Theists he gives up his omniscience because, in a logical extension of Arminian libertarian free will arguments, it cannot coexist with creaturely liberty.

Once kenosis becomes an axiom it seems always to go further – a kind of theological version of Daniel Dennett’s universal evolutionary acid. Robert J Russell, for example, builds his whole view of cosmic eschatology by going “beyond mere kenosis“, a whole future universe built on a sandy foundation. The recent column by Thomas Jay Oord on BioLogos pushes kenosis as far as it ever seems likely to be pushed, short of saying that true kenotic love entails the suicide of God, which would achieve the first Evangelical Death of God theology! (The rather muted comments at BioLogos suggest that Oord’s theology breaks the bounds even there, for most readers if not for those who commission articles). But to Oord, since the Philippians proof-text shows that divine love is all about giving up divine attributes for the sake of others, then to be truly loving God must, by necessity rather than choice, be empty of the attributes of power and knowledge. Even to create ex nihilo would be an unjust coercion of … nothingness… and, of course, of the creatures which God forces to exist (as puppet master).

Once kenosis becomes an axiom it seems always to go further – a kind of theological version of Daniel Dennett’s universal evolutionary acid. Robert J Russell, for example, builds his whole view of cosmic eschatology by going “beyond mere kenosis“, a whole future universe built on a sandy foundation. The recent column by Thomas Jay Oord on BioLogos pushes kenosis as far as it ever seems likely to be pushed, short of saying that true kenotic love entails the suicide of God, which would achieve the first Evangelical Death of God theology! (The rather muted comments at BioLogos suggest that Oord’s theology breaks the bounds even there, for most readers if not for those who commission articles). But to Oord, since the Philippians proof-text shows that divine love is all about giving up divine attributes for the sake of others, then to be truly loving God must, by necessity rather than choice, be empty of the attributes of power and knowledge. Even to create ex nihilo would be an unjust coercion of … nothingness… and, of course, of the creatures which God forces to exist (as puppet master).

Therefore, God must instead be responsive to a pre-existing (presumably eternal) cosmos… which raises all the classical philosophical bogeys of how such an all-loving God came to be a part (and just a part) of what exists, whether other gods who are not all loving exist to compete with him (and if not, why not?), why love should be ontologically prior and necessary when God’s other attributes appear accidental and changeable, etc, etc.

But none of this would have any justification from Scripture, at least, if Paul had worded just 3 verses in his letter to the Philippians differently (or to be precise, if interpreters had been more fastidious in understanding his meaning). Or then again, had recent theologians been seeking the “whole counsel of God” rather than proof texts for “self-emptying”, they’d have seen that Scripture elsewhere is much more concerned with the human Jesus being full of God, rather than with the divine Son emptying himself of Deity. The Bible actually teaches the self-filling, not the self-emptying of Jesus… which follows through to a very different theology of God, nature, salvation and inspiration.

John in the prologue of his gospel, for example, makes the astonishing claim that the Jesus he knew personally was the very Logos God spoke in Creation to make everything that exists. But he doesn’t stop with that description of Jesus as God – he goes on to the Incarnation in v14:

The Word became flesh, and made his dwelling among us. We have seen his glory, the glory of the One and Only, who came from the Father, full (pleros) of grace and truth.

If the eyewitness saw Jesus in terms of the fullness of divine grace and truth, and a contemporary theologian sees him as self-emptied and prone to misunderstand the Bible, which testimony do you prefer? Whether 1 John had the same author as the gospel, or a different John, it too claims eyewitness status. It begins:

That which was from the beginning [ie God], which we have heard, which we have seen with our eyes, which we have looked at and our hands have touched – this we proclaim concerning the Word of life. The life appeared; we have seen it and testify to it, and we proclaim to you the eternal life, which was with the Father and has appeared to us.

And if a reader had asked John what he actually saw and heard, do we think he would have replied, “Just an error-prone man, actually – the divinity was set aside, you see, to show God’s love better”?

The writer to the Hebrews is equally concerned to show both the true divinity and the true humanity of the Jesus who lived, died and rose again in Judaea. His letter begins by setting the human Jesus in his revelatory setting:

In the past God spoke to our forefathers through the prophets at many times and in various ways; but in these last days he has spoken to us by his Son, whom he appointed heir of all things, and through whom he made the universe.

We note, in passing, that if he is describing Scripture in “incarnational” terms, it is to compare the divinity of the prophets’ words with the divinity of the Son, not to emphasise either or both as primarily human. But to proceed, it is in this incarnate state, as the one whom God sent to speak to us, that the writer now describes Jesus:

The Son is the radiance of God’s glory, and the exact representation of his being, sustaining all things through his powerful word. After he had provided purification for sins…

There is no “emptying of the divine” here – it’s not that the Son was once the radiance of God’s glory, gave it up, and has become so again on his return to heaven – instead something in the human Jesus could be perceived to be the exact representation of God’s being (the word is hypostasis, the basis of classical Christianity’s insistence on the single hypostasis of Jesus as the full expression of both human and divine natures). As others have pointed out, had Jesus divested himself of his divine attributes, he would no longer have been sustaining all things in existence by his powerful word (implying both omnipotence and omniscience) whilst on earth, and there would have been no earth nor anything else in existence. Meanwhile, we are told, he was making a pig’s ear of interpreting the Scriptures he had himself spoken. Excuse me if I disagree. Strongly.

Furthermore, of course, we should remember that his return to “the right hand of the Majesty in heaven” was still in the form of the man he took on earth. His full glory had been occluded to human eyes, but never given up.

My last witness is Paul, whom you may remember wrote Philippians, and may be assumed to be consistent on such a weighty matter. In Colossians 1.19 he writes:

For God was pleased to have all his fulness (pleroma) dwell in him, and through him to reconcile to himself all things, whether things on earth or things in heaven, by making peace through his blood, shed on the cross.

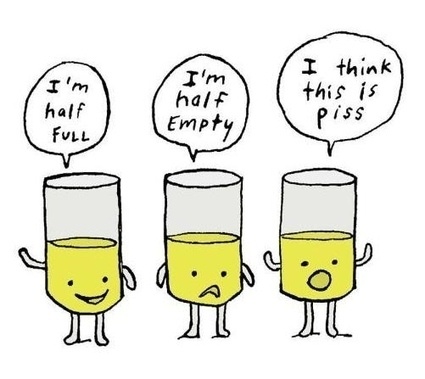

Now Vine says that God’s “fulness” is the completeness of his being – all that he is. And that is in accord with the historic doctrine of divine simplicty, for the notion of God’s consisting of interchangeable parts like love, knowledge or power, of which he divests himself sometimes like a wooden leg, is nonsensical. If Christ on earth was, as Paul claims, indwelt by all the fulness of God, then Christ did not empty himself of anything to become man. Or he’d have possessed the half-fulness of God, right? Lest we think it a slip of the pen, Paul repeats in 2.9:

Now Vine says that God’s “fulness” is the completeness of his being – all that he is. And that is in accord with the historic doctrine of divine simplicty, for the notion of God’s consisting of interchangeable parts like love, knowledge or power, of which he divests himself sometimes like a wooden leg, is nonsensical. If Christ on earth was, as Paul claims, indwelt by all the fulness of God, then Christ did not empty himself of anything to become man. Or he’d have possessed the half-fulness of God, right? Lest we think it a slip of the pen, Paul repeats in 2.9:

For in Christ all the fulness of the Deity lives in bodily form, and you have been given fulness in Christ, who is the Head over every power and authority.

Against those apostolic testimonies are opposed a misinterpretation of Philippians 2, and the human conjecture that for Jesus to be fully human, he would have to be prone to error. People ask, “Didn’t Jesus ever mess up a joint when he was leaning carpentry?” But why, as a believer, would anybody think that an important question? If he did, clearly his disciples never thought it a matter worth mentioning, given they saw the pleroma of God in him.

Our choice, it seems to me, is to take one text (in preference to at least 4 others), together with some human reasoning, to say that Jesus emptied himself of divinity (and then rewrite all the Christian theology of God, nature and salvation to fit). That, I guess, frees us up to teach Jesus better ways of interpreting Scripture in the life to come and even, perhaps, to get him to brush up his theology in line with modern insights.

Or we can take all those texts (together, of course, with what the rest of Scripture testifies) and bow in wonder and astonishment at Jesus, the man filled with all the fulness of God, who nevertheless made himself nothing, taking the form of a man and speaking the very words of God even as he sustained the cosmos in being.

I don’t see how one can do both, though.

Hello, Dr. Garvey!

My eyes are doing much better. Thank Jesus for his gift of doctors! I have a question this is more history than science; however, I would like your opinion on it. I am sure you know the concept of the Dark Irish. I have a book by a Catholic priest long dead who stated that Spanish settled in Ireland as a result of the Spanish Armada. He believed it, but is there any scientific proof of it? My mother’s family claimed to be Dark Irish as well as Palatine Irish. As a German scholar, I know that the Palatine Irish are true; however, what about the Spanish Irish. My father had dark hair too, butt he was English, Welsh, Scottish, Scots-Irish, and Belgian. I have some cousins that are red heads on my father’s side, of course. My hair was black before it turned silver. As a doctor and scientist, what do think about the Spanish Armada legend. God bless. I hope you do not mind my curiosity.

Hi Henry. Glad to hear about your eyes!

Half remembered history – there’s no doubt that some of the Armada guys were washed up in Ireland – I think most of them suffered a sticky end from cold, hunger and hostility. It might be difficult to prove anything genetically (a) because there wouldn’t have been that many and (b) because the original Irish population migrated from the Iberian peninsular before the land bridge broke down after the Ice Age. so the founder effect might well lead to quite a few “dark” genes from then. (My lot, allegedly, were late arrivals from Gaul after Roman times!)

The other complication would be that, as a rebellious Catholic country, no doubt a number of Spaniards turned up there at other times. So ends my authoritative knowlegde of Irish history!

Thanks, Jon.

It is always good to hear from you. Take care. I read the things here you write. Very interesting.