Spending a sweltering summer bank-holiday Monday on an overcrowded Lyme Regis beach with my grand-daughter and her mother last week was a duty rather than a joy. The book on Lyme I’d brought along to read between building sandcastles and queuing for fish and chips told me that the town’s resident population of 3,000 expands to 15,000 on a hot summer’s day, and I could well believe it as they had all apparently encamped on the same small area of sand as us.

But before Lyme Regis acquired world fame through Jane Austen’s Persuasion and Mary Anning’s fossil discoveries, it was just a small mediaeval sea port with an inadequate harbour. In fact, it seems to be the case that coastal settlements were either, if blessed by a harbour, commercial ports devoted to trade and vice, with the inhabitants liable to be press-ganged into the navy, or if not they were impoverished villages struggling to claw out a bare existence from fishing, supplemented where possible by smuggling or wrecking.

The only reason respectable people had to visit the coast was if they were shipwecked on a voyage to somewhere more worthy, and then their littoral acquaintance was likely to be limited to being dashed against the cliffs or murdered by the local wreckers.

All that changed (as I found in my Lyme guide book) in 1750, when a Lewes physician named Dr Richard Russell published a Latin dissertation on the benefits of bathing in, and drinking, sea-water, particularly for “affections of the glands”, meaning mainly tuberculosis. This was in 1753 translated into English. At the time the fashionable and rich already resorted to spa towns like Bath, but Russell claimed that sea-water was superior to all these: the fact that he lived near the sea rather than a spa, built a large house and treatment-centre in the down-at heel fishing town of Brighthelmston (soon to become Brighton) and made his fortune there may, perhaps, have guided his theorising.

Be that as it may, the theory came at the right historical moment to become fashionable, and as his Wikipedia page states “few disputed its value”. Certainly he was elected to the Royal Society for it as early as 1752. After his death, his sea-water therapy gained ground by its inclusion in a popular medical book of 1769, Domestic Medicine by William Buchan, which sold 80,000 copies. Additionally, his former house, being grand, was let to the Duke of Cumberland, who was regularly visited by his nephew the Prince Regent, so that the sea treatment now acquired royal patronage.

Russell’s theory was as unfalsifiable as astrology or natural selection, and relied for its popularity on its being of the times and, like its contemporary foxhunting, a craze for those with plenty of money and not enough to do. It therefore seems absolutely typical of Popper’s (if not Feyerabend’s) category of pseudoscience.

Like the regime at the spas, sea-bathing involved the rich putting up with maltreatment mitigated by being in fashionable company and undertaking fashionable leisure pursuits, at the right time and place. In this case, the right place was anywhere that could kit itself out with bathing machines and the therapeutic paraphernalia, together with the right kinds of ball-rooms, hotels and similar entertainment to attract the in-crowd. The right time was the autumn and winter, because the value of sea-bathing came partly from the coldness… which, naturally, fitted well into the the social calendar, as the summer months were spent at ones country estate, after which the “season” began.

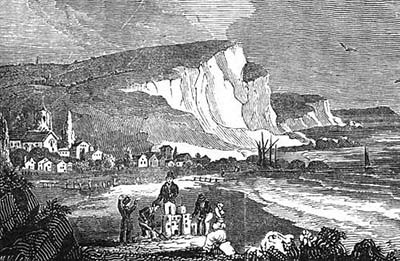

And so resorts like Brighton, Scarborough (which was also a spa), Blackpool Cromer, Margate and Weymouth started to grow in size and wealth beyond anything local industry could support. Some resorts were also able to cash-in on the Romantic movement’s attraction for wild scenery – previously satisfied by the sublimity of mountain landscape. Lyme Regis had such dramatic cliff scenery, but also the advantage of the eighteenth century elite’s fascination for curiosities like fossils, which it had in abundance (later to be made world-famous and more scientific by Mary Anning).

And so, for the rich, the sea became for the first time associated with grandeur rather than terror, wealth rather than poverty, fashion rather than backwardness, and culture rather than ignorance. Painters would have a comfortable base for creating picturesque coastal scenes. Writers like Austen would spread the word in print.

Fast forward now a few decades, and the rapidly expanding railways, already rich from their carrying trade between cities and to and from big ports, were looking to make more profits from passengers. This fortunately coincided with an enlarging middle class, and a richer urban working class, given time off from paid work. The natural solution was not only to organise train-loads of passengers to enjoy the pleasures of the rich at the seaside, but to use their profits to build up new resorts with rather more modest hotels and more bourgeois entertainments. And so the rail network prospered because of sea-bathing, and sea-bathing because of the railways.

I suspect that one element may have been the need to fill the trains, and resorts, outside the wealthy’s winter season. This meant the hoi polloi being encouraged to take their holidays in summer – which paradoxically meant they might actually enjoy bathing in warm seas, whilst their children might (by 1838) stay on the beach and build sandcastles without dying of exposure.

This democratization of sea-bathing began to dispense with the pretence of medical value – except in the vague sense that fresh air, leisure and swimming were “good for you”. After the Second World War, when the seaside had become the holiday destination for all, sunshine became healthy as well – and a sun-tan a sign that you could afford lengthy holidays on sunny beaches, rather than, as before, an indication that you were a labourer or a sailor. And so we can trace the tanning industry – not to mention the bikini and speedos – back to Russell’s dubious science.

Just think, now, where Russell’s pseudo-science has taken us from a possible world in which the coast would still be deserted except for navigators and fishermen. Across the whole world, seaside resorts are the leisure destinations of hundreds of millions: airlines rely on an international traffic for this purpose, and have filled the air with CO2 and noise because of it. For some countries it is the major part of their economy. The holiday hotel, wherever it is found now, is modelled ultimately on the establishments lining Georgian and Victorian promenades.

Off the back of this association of the seaside with pleasure, the coast has become a desirable place for the well-to-do to live, and to explore for its own sake, and water an inviting, rather than a feared and alien, element. In the 18th century, even most sailors couldn’t swim – it seems probable that only the craze for sea-bathing made swimming popular, and therefore we now have pools even at inland hotels and in every town, and in private houses too, as a status symbol. And for the same reasons swimming has become a popular sport. But swimming itself led to other activities like surfing, or scuba diving, or water polo.

Trip round the bay c 1917 – my granny and her parents standing near the bow. The boat is named after a heroic lighthouse-keeper’s daughter – perhaps the public identified with her because they visited the seaside.

Those first fashionable seaside visitors admired the picturesque fishing boats they found there and, presumably, sometimes paid to take trips on them. This led in the more popular age to “trips round the bay” in boats built for the purpose. The occasional rich regular visitor might even learn to sail his own boat – and that, also increasingly extended to the masses, became the basis for millions of people now to be engaged in sailing, power-boating, sea-fishing and other watersports.

I could go on at length about the changes – many beneficial – that have affected numerous aspects of modern life because one man invented a pseudoscience nearly three centuries ago. But you can have fun working it out yourself by imagining what the world would be like if nobody had any more reason to visit the coast than they have to visit, say, an industial site. No picture-postcards, perhaps. No upgrade houses for millionaires around Sydney Harbour or Sandbanks in Dorset. No sun-loungers, sun-beds or melanoma scares. No beach volleyball. No rock-pooling. No pop-up tents that refuse to pop down. A completely different world, in fact.

And most of all, no sitting on a sweltering beach amidst thousands of sweaty chavs trying to keep sight of your granddaughter whilst snatching some reading time. That’s what pseudoscience does for the world!

It appears that injecting sea water (Ocean Plasma) is very efficacious in treating TB.

Better than bathing in it or drinking it 🙂

http://oceanplasma.org/documents/simonroberte.html

Sounds good, Ian – no more unsightly bathing machines having to be converted to beach huts. Just piles of used syringes…

I think it was accepted for the same reason evolutionism is. It was not scientifically studied but it was presumed it was.

Yet they would of said experts had studied it.

So a close examination was needed. likewise evolutionism needs close examination to see if its a hypothesis of science.

it ain’t but creationists need to do a better job of showing why not.

Robert

“Evolutionism” is usually (though admittedly not exclusively) applied to the philosophical position that everything evolves, and so is neither a scientific hypothesis nor empirically verifiable by definition.

I would, of course, disagree with your assessment of how much evidence for evolution there is (defined minimally as descent with modification).

That said, one interesting consideration for something like sea-bathing is that it’s as unlikely that any controlled trials have been done to disprove its efficacy as that they were to prove it.

As I said in the OP, it was accepted because it was of its time, but then along came the germ theory of disease, and “lymphatic disorders” were blamed on Mycobacterium tuberculi and chemicals that would poison the bacteria were the thing to find. Bathing machines at Brighton quickly became simply “old hat quackery”.

For all we know from “the literature”, though, the regime might have been much more effective than placebo – but who’s going to set up the research during any British winter soon? That may sound unduly credulous, but I remember a paper (quickly forgotten, of course) during my medical career that demonstrated hot water bottles to be more effective than non-steroidal anti-inflammatories in the pain of both osteo and rheumatoid arthritis. But there’s not much profit for Eli Lilley etc in hot water!

Evolutionism is a useful term for defining evolution proponents. Words change meaning over time.

I don’t agree anything is of its time.

If a controlled experiment by a researcher was done on sea water and published loudly and proved it was untrue claims then it would of been accepted. So the times would of changed.

Its just people and no times.

We canm chage, or introduce any correction or error anytime.

We can change, or introduce any correction or error anytime.

Of course we can – the issue is that we usually don’t. To take your example, it’s possible that if some over-funded researcher did some research that confirmed sea-bathing as useless, it would get some column inches in the science pages of the Daily papers, with quaint pictures of bathing machines and stripey costumes. It would fit the narrative.

But if an enthusiast did some trials and found a significant benefit from seawater in TB, it would get lost immediately – and quite probably the guy would never get research funding again.