In my last post I drew on George Berkeley in the context of probability theory, to show how western thought’s tendency to make abstractions from reality actually leads to a misleading view of the world. The generalisations of science are particularly prone to the reification of abstract notions.

One example from biology that I noted back in 2014 is the way, in classical adaptive evolutionary stories, that single traits are attached to single survival criteria divorced from the complex and messy reality of the real creature and its world (or rather, God’s world). There I quoted Craig Holdrege on the misuse that has been made of the giraffe by evolutionists from Dawkins to Darwin (and in this particular case, even before him, to Lamarck):

Both the trait (“long neck”) and the particular survival strategy are products of a process of abstraction from a complex whole. Therefore we can think them clearly and establish a clean and transparent explanation that seems to work — it makes sense that the long neck evolved in relation to survival and feeding habits. Unfortunately — and it is the price we pay when we operate with abstractions — we have lost the giraffe as the whole, integrated creature it is. We’re not explaining the giraffe, we’re explaining a surrogate that we have constructed in our minds. The animal has become a bloodless scheme. For this reason evolutionary stories are usually woefully inadequate.

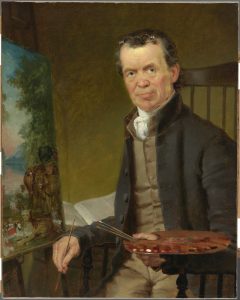

I look at some of the backstory to his remarks in the rest of that post. But today, I want to use the excuse opportunity of the theme of abstraction to illustrate another example, that is, the painting by the naive Quaker artist Edward Hicks (1780-1849) on the cover of my book, God’s Good Earth. The publishers having seen fit not to credit him anywhere, a few people have asked me about the image, and it’s an interesting story.

There’s a pretty reasonable Wikipedia page on Hicks, to which I refer you. But briefly, he was trained as a coach painter, but became a convinced Quaker, to the extent of becoming a preacher.

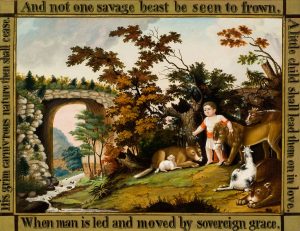

His beliefs conflicted with his love of painting, leading to a tension within himself and to problems within his denomination, which disapproved of decorative painting. But he returned to art partly for economic reasons, and yet his rather naively conceived pictures closely reflect his faith. In particular, he returned over sixty times to a single subject, The Peaceable Kingdom, which he executed in numerous different forms for friends and others.

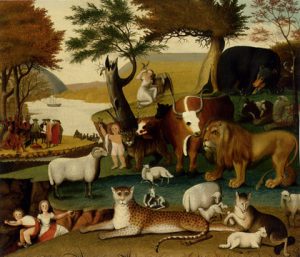

The excellent graphics department at Wipf and Stock suggested the painting to me when the photograph I fancied would have cost a fortune in licence fees. I fished around the various versions on the web, and picked the one that seemed best to reflect my book’s contents.

The excellent graphics department at Wipf and Stock suggested the painting to me when the photograph I fancied would have cost a fortune in licence fees. I fished around the various versions on the web, and picked the one that seemed best to reflect my book’s contents.

In some ways, the painting’s subject is slightly tangential to my book’s theme, which is the goodness of the present creation. Hicks’s conception, however, is primarily about an Edenic future, which, however, he hoped to see established in the new land of America through the peaceful precepts of Quakerism.

The composition is drawn from Isaiah 59 and 65, in which the wolf lies down with the lamb, the baby plays safely with the viper, and a little child (whom he interprets as the Christ child, at least sometimes) shall lead them.

What is so interesting is that, not only do the elements and even the style of the various versions differ enormously, although there are common recurring elements, but even the message of the piece appears to change over time.

For example, many versions feature in the background the Quaker William Penn’s peace treaty with the Lenape native Americans in 1683, clearly intimating that this kind of peaceful coexistence amongst men ought to be, and can be, achieved.

In later versions, this scene seems to be replaced by groups of Europeans in similar converse, and this appears to represent the healing of the unfortunate split that occurred within the Quakers themselves, led on on one side by Hicks’s own cousin. This conflict was a hindrance to Edward’s own faith and preaching, and the pain seems to feed into some of his compositions.

All these elements are representative, in some way, of the theme of redemption, present or future. But my point here is that it would be a mistake to see this large series of paintings as simply alternative “versions,” from which one can abstract a single meaning. Rather, what I love about the pictures is that each one tells a somewhat different story, despite the recurring visual and conceptual themes. To me it is as if we are seeing Hicks’s worldview – which is to say his faith – working out in the changing, individual circumstances of life. The themes, or patterns, only really make sense in the context of the individual, contingent, scene.

I may be over-fanciful in this, but I see in this an echo of what George Berkeley is getting at in his dislike of abstraction. It is only in nitty gritty reality that laws or principles have, themselves, any reality. They do not transcend contingent events – they depend on them. Maybe that’s also why God’s word to us in the Bible predominantly comes in the form of a narrative, not a treatise. The reality we have is the only reality there is, being the one God has actually created. It’s a deep thought.

Incidentally the particular painting of which my cover is a detail is displayed in the Dallas Museum of Art.