In The Generations of Heaven and Earth I make a case for the Genesis 1 creation story being in essence a phenomenological, rather than an ancient “scientific,” account of the world, though that is complicated by the author’s concept of this creation as a temple reflecting the form of the wilderness tabernacle and/or the Jerusalem temple.

That passage in my book was developed from various explorations of the theme here on The Hump, in which I included the suggestion that to a scientifically naive person with limited geographical knowledge, such as a modern child or an ancient adult, something like Genesis 1 describes pretty well one’s experience of the world, without speculation on the things not experienced.

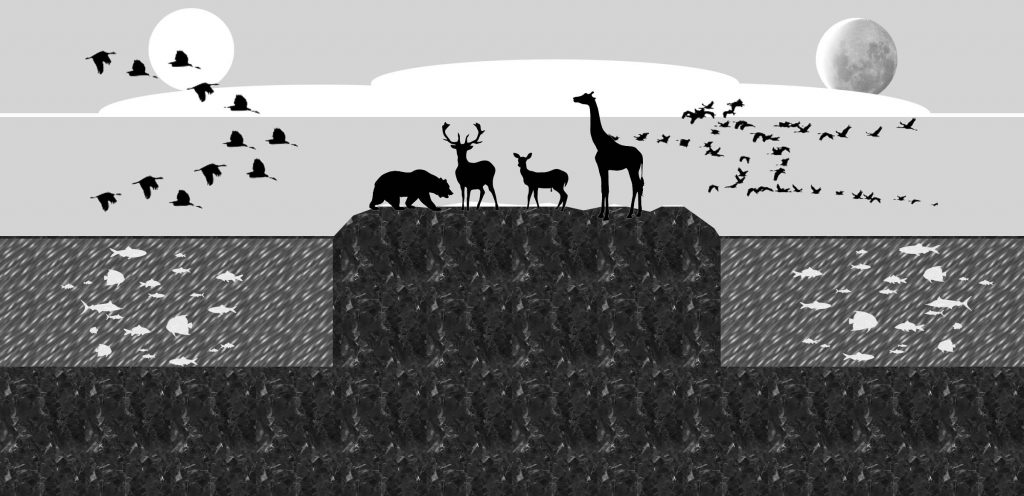

Here is the illustration of Day 6 from my book.

The world, as you see, is conceived as a layer-cake of indeterminate lateral extent (much as most of us nowadays thing of the universe as a three-dimensional collection of galaxies with no definite boundary), simply because no such boundary has been experienced. To the Hebrews, this layer cake is “the heavens and the earth,” a term naming the extremes and including all that is in between.

The bottom layer is the earth (Genesis 1 mentions no underworld), and no attempt is made to understand its depth or any limits, again because these are unknown, The top layer is the heavens, or shamayim, which may equally be translated “sky” or “expanse” but not (as I have argued elsewhere) “firmament” in the sense of a solid sheet or dome.

The complication is that almost certainly the “upper waters,” separated from the lower waters that became seas, are the clouds, whose physical function throughout Scripture is to deliver rain. That would make “sky” a vague term for the space under the clouds, but with an ambiguous reference to the distant blue “something” always know to be above the clouds. Scripture makes reference to “the highest heaven” as the unique dwelling place of God, the place of the “light” of Day 1, but also refers to the heavens as the abode of the birds, which is clearly much lower.

In an old post I also pointed out the Bible text in which Absalom, caught in a tree by his hair, hangs “between heaven and earth.” Somehow, the sky seems to refer to anywhere “up,” that is above the normal human dwelling space – much as tall buildings now are known as “sky-scrapers.”

This week, with my four-year old granddaughter staying, I realised I had a fast-disappearing opportunity of quizzing a pre-school age child on her cosmological view before it becomes educated out of her. The immediate prompt was the picture she drew that is absolutely typical of how young children picture the world. This is Martha’s effort, uncannily similar to my Genesis summary apart from the wider colour palette:

The drawing was done spontaneously, but today I quizzed her on the understanding lying behind it. As you see, There is a clear green base placed at the very bottom, which she told me is the ground. At the very top is a blue boundary which is, she said, the sky. The human (and canine) interest is resting on the ground – it’s the family, and I’ll leave you to guess which one is me (but Martha is the smallest, in blue).

Things become interesting when you realise that the sun (children always include the sun – I wonder why) and the clouds occupy the same space as the people, one of the clouds actually touching the head of one of the adults. Yet Martha assured me that the sun and the clouds are “in the sky” (not “below the sky”), and the human figures are not. And so, in the childhood universe, the sky is both anything “up there” and a definite blue “something” marking its upper limit. Incidentally, in another picture she drew birds remarkably like those in my picture – also “in” the sky, just as the birds of Genesis 1 are the product of the upper waters and fly in the heavens.

I then asked Martha what the blue sky was actually made of. This she simply had not considered before, but upon reflection upon my leading question whether it was hard or soft, she settled on “soft.” No theories of a solid firmament, then. When asked if anything was above the sky, she had nothing to suggest. And that’s obviously why it is at the very top of the paper.

A similar lack of specificity met my enquiries about what was under the ground, and how far it went. She sagely offered that there is soil. And when pushed she added “worms,” eventually specifying that there were probably at least ten. But the thought that there might be a bottom to the soil, or that it went on forever, were simply outside her range of considerations. The ground is the bottom of her world, and the sky is the top.

When I asked her where the moon was in her scheme, or where it hid during the day, she had nothing to suggest. Out of sight, out of mind. Moses was certainly ahead of her in including a concept of night – but then he didn’t go to bed at 7.00pm.

So I asked her how far she thought the world extended to either side of where her picture ended, and she ventured that when she had come in Daddy’s car to our house, it was a long way. It took some prompting from me to decide what might happen if one kept driving even longer, until the petrol ran out – would one keep going forever, or come to some kind of end? She opted for a finite world, not surprisingly, rather than one that goes on forever, but the fact is she had never thought about it: what mattered was that as far as she had ever traveled (and she has flown abroad), the sky was up, and the ground was down. In other words, she has no idea of the concept of a “cosmos” as a closed system of some particular shape, limited in size up, down, or sideways – nor of something that is infinite in any of these directions. Not surprising, as it was the Greek philosophers who originated that idea. Consequently she does not “believe” in a world that is flat, or round, or anything else, and I’m pretty sure that the writer and readers of Genesis, and other pre-scientific and pre-Greek texts, had a similar worldview.

That’s not entirely true in Martha’s case – when pressed about what would happen if one kept driving and driving, she fished out of her memory the idea that the world is round, and gestured a flat circle with her arms. I’m pretty sure that was the beginning of her adult education creeping in, her child mind misinterpreting some older person’s statement that “the world is round.”

Within our conversation, however, it settled her slight concern about the boundaries of the world to see it like a plate which would limit how far you can travel. It’s a naive concept – but remarkably similar to the Babylonian world map that is the first graphical representation of the world of which we know. It probably arises from the idea of the horizon seen at sea, or from a high mountain – but that is beyond the experience of my granddaughter, so I suspect she takes it on trust from some adult or her older sister.

So, all in all, my conversation with Martha confirms my impression that there are questions you don’t even start asking about the world until some educational system challenges you with them. I’ve said before that I vaguely remember as a child being told that the world was a sphere, and asking all the usual questions about why the Australians don’t fall off, before I started trying to dig through to them from Exmouth beach. Martha will begin to reach that level of sophistication not long after she starts school in September.

Somehow it seems a bit of a shame.

Jon,

This is lovely. And, yes it is a shame. If all of us, especially the politicians and other elites could be magicked back to a child’s view of the world, just think…

Still, there would probably be fights over toy trucks and balls and such, but beats what we have now.

Well, I’m happy that the phenomenological will come to give way to the scientific as Martha grows up – though I’ve benefited from rediscovering an anthropocentric and intuitive experience of the world.

I do suspect a true science would integrate them better than what we have now.

I’m watching a vigorous older man with 400 acres and no money describe how he carved out his life, his houses and homes, food and a family using ingenuity and elbow grease. He had a ball for 50 years creating a slice of heaven this side. Planted 40,000 Christmas trees to earn a buck.

If we could take our youth and expose them to a hands on homestead approach to living, we might have fewer murders in our cities.

Strange though how human nature hasn’t changed much over all these years when we decided we were finally civilized.

Hi, @outforlunch, and welcome to The Hump

Your old man knows the truth of working with his hands and “bearing his own load” as St Paul puts it. It begins to look as though both our youth, and those of us who have become “domesticated” – will be forced to learn those motivations and skills anew as the cities increasingly self-destruct.