A friend of mine is wrestling, candidly and productively in my view, with the hype of climate change. On the one hand he sees that there is so much in the mainstream account that is just nonsense, both regarding climate change itself, and the proposed solutions such as those fudged at COP26. On the other (if I don’t misrepresent him) he finds it hard to believe that a whole scientific community is complicit in deception, and also feels that the existence of harmful warming is undeniable, affecting the poor most of all. One example he cites is his own experience of extreme temperatures when visiting Delhi a few years ago.

The question is important to Christians in particular, I think, because the image of the world’s poorest burning up and dying of drought and starvation is the most legitimate motivator for our compassion, and hence buying into the climate change agenda. So it is worth addressing. The retreat of glaciers seems somewhat more removed from human need, and only the eco-warriors get more than mildly worked up about plastic straws, and even they are silent about the vast amount of plastic waste from either COVID PPI and test-kits, or from renewable energy technologies.

It is self-evident that any change in weather patterns will adversely affect some, even if others benefit. One has only to consider the catastrophic crop failures in Northern Europe during the Little Ice Age, or the hardships of US farmers in the 1930s Dust Bowl era, to realise that. Still, before any assessment of net harm or benefit, and before attribution of causation to mankind, one needs to get the facts straight. So I decided to check out the data behind the headlines regarding climate change in India – surely the index case for a populous, poor, region. And I majored on Delhi, since that was the focus of my friend’s anecdotal evidence of heatwave conditions.

The first question to ask is whether a heatwave or a record local temperature is any indicator of global warming. Heatwaves are one of the only two weather extremes (the other being “extreme precipitation” but not flooding) that the IPCC summary report actually says have increased worldwide. But digging into their report, even those were claimed in only one scientific paper out of over forty that found no trend in extreme weather, and it is worth asking why that was the one the IPCC headlined… and, of course, why delegates at COP26 blamed all extreme weather on warming, in despite of the IPCC report that supposedly informed the conference.

But we had droughts and heatwaves in the past as well (I remember England’s brown fields in 1995, though the UK’s worst recent heatwave and drought was way back in 1975-6). Also, record temperatures happen all the time and are not good indicators of trends – the Antarctic interior experienced its lowest ever recorded temperature this year, and one of its coldest winters.

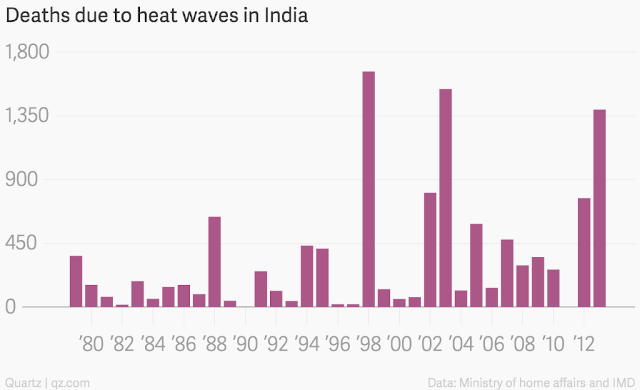

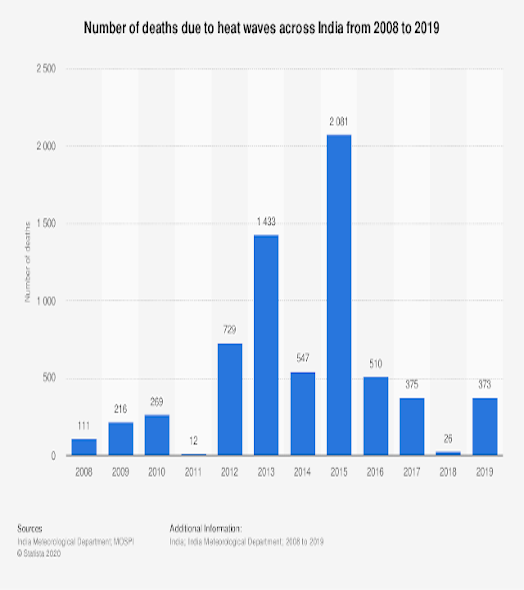

Here are a the two best charts I could find to cover heatwave deaths in India for as many years as possible:

The overlapped periods show the charts are comparable. To me it looks as though 1980-1997 was a relatively good period (and who knows what was happening before then, perhaps in the 1930s?), but whilst there have been more peak years in the time since – in 1998, 2002, 2003, 2013, 2015 – it’s hard to see any trend within in that later period, especially when you factor in that the population of India has doubled linearly since 1980. The 1,600 or so deaths in 1998 would therefore be the equivalent of 2,400 now, which is significantly more even than the record year of 2015. There’s been nothing to see since then.

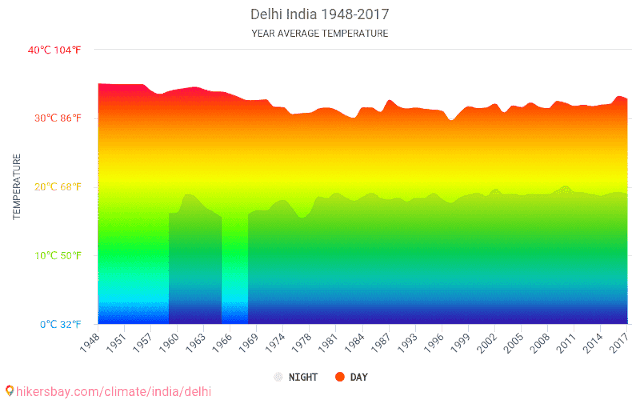

Overall though, The Indian government denies there has been an overall increase in temperature (this article links to their report), and that seems to be confirmed by a graph I find on the web for Delhi itself, the 1950s being hotter presumably despite an increase in the industrial heat island effect in recent years:

As for record high temperatures, based on 100 years of records:

“And, the highest ever temperature reading during the same period is 48.4°C (119.1°F) recorded on 26 May 1998, again at Met Delhi Palam.” (Wikipedia)

This seems a tad higher than a 48 degree high recorded there in 2019 (for some reason reported as “the highest ever” and compared to 47.8 in 2014 in The Statesman – which sounds like another case of ignoring records before certain dates to push the warming narrative). The full dataset of peak summer temperatures would show what’s happened in the last century better, but the point is that the hottest day ever in Delhi was actually 23 years ago. If, then, Indians are suffering the increasing direct effects of global warming, it does not appear in the records.

Incidentally there is also no recorded increase in India’s tropical cyclones either, and that matches the lack of a trend for hurricanes worldwide – not surprising as they are driven by the difference between tropical and polar temperatures, which decreases with overall warming.

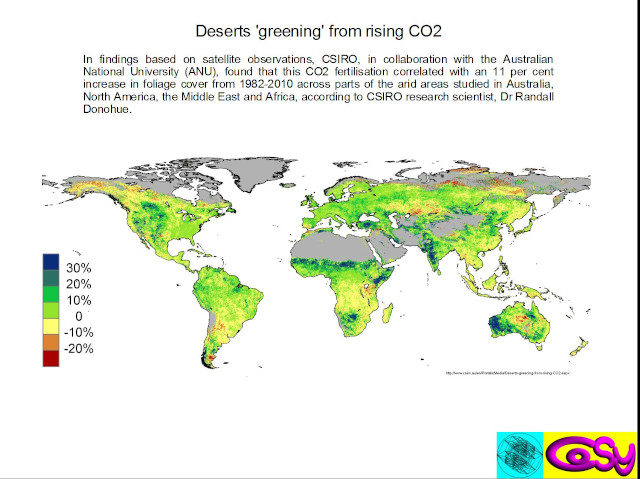

Meanwhile India’s food production – surely what most people here imagine when they are told the poor in the developing world are suffering from climate change – is actually at record levels, partly from improved farming methods and seed varieties, but also because of CO2 greening and, in dry areas, the lower requirement for water with higher CO2. India is in fact a success story in the reduction of extreme hunger (whilst still being a poor country per capita). Here is a global map showing CO2 greening from 1982-2010, showing up to 30% greater foliage cover in parts of India:

Whilst this map is before you, notice that the Amazon basin was mostly greening at the very time when the environmentalists told us it was dying from deforestation. The Sahara Desert is retreating. The map shows that Britain is greening too, which doesn’t quite match Chris Packham’s post-COP26 lament that the world is going to hell in a handcart, unless he’s worried about crop yields in central Australia and Patagonia.

All this information (assuming it’s been clocked by the Indian government and its scientists) may well explain their copping out of COP26, and notably their much-publicised bucking of the fossil-fuel restrictions advocated there. What has driven their increased resilience has been the decrease in poverty, which as always has been dependent on the easy availability of energy. If they can’t see much wrong with their weather, and a lot that’s right with it in producing more food and jobs, then their self-interest is clearly served by building more power stations. The local pollution problems affecting Delhi this week may seem a worthwhile cost for now – and remember that it comes from coal particulates, and not from carbon dioxide.

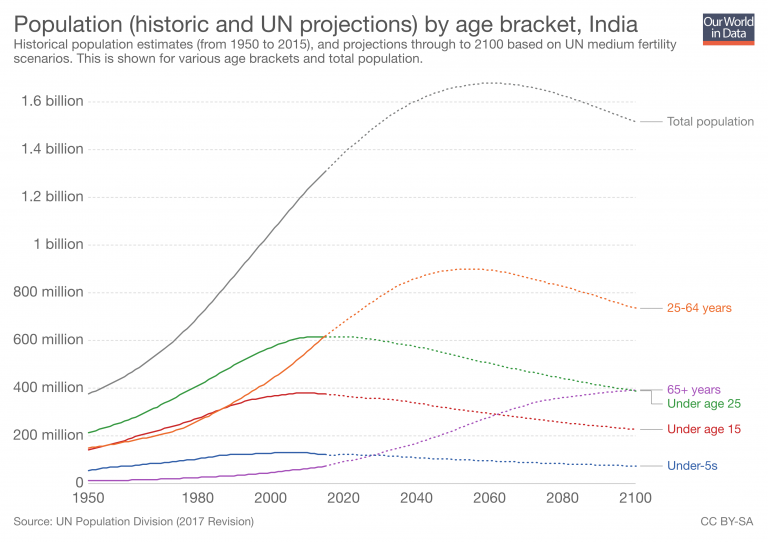

India’s population is expected to peak around 2060, but that is likely to depend on the reduction of poverty. The population of children has already peaked – the demographics indicate the future:

Currently, India’s production is slightly outpacing population and looks likely to serve their population peak. But if energy costs escalate, and production drops, it is that which will devastate the poor.

India’s governors may also be quietly questioning the whole worldwide alarmist narrative, and reasoning that impoverishing their own folks would not even contribute to the good of the world. If so they are a lot better informed than our own political class, who appear to get their agenda as a job lot from Klaus Schwab.