In June I did a post to show that ancient cosmologies, including that of Genesis, were not so much old-science, or even pre-science, as altogether indifferent to the physical and therefore a-scientific. It occurs to me it would be interesting to go on to show how cosmologies have changed over the millennia, and where we end up today. This has already helped me clarify issues in the science-faith discussion, so maybe it’ll give you some points to ponder as well.

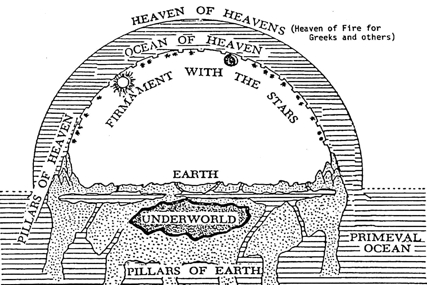

In the previous post I showed how this popular “ancient cosmology” is actually a modern materialist interpretation of biblical passages:

I don’t believe any Hebrew ever saw the world like this. To the writer and readers of Genesis, I believe the “heavens and the earth” created by God looked more like this:

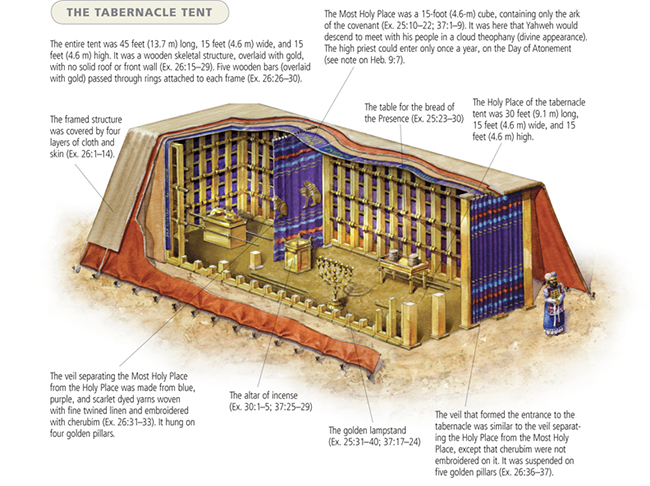

…or in later centuries, like this:

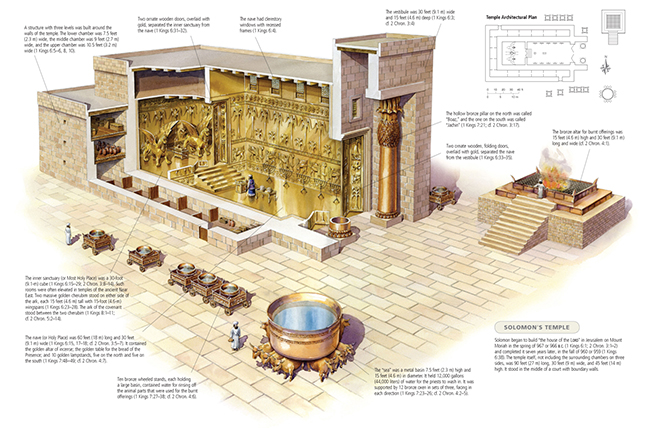

…or in later centuries, like this:

There seems little doubt to me that Genesis 1 is, technically, a “temple inauguration text”, with the Cosmos as God’s “real” temple (of whose pattern the tent and Solomon’s building are imitations, Ex 25.40). Let’s use these pictures, especially the tabernacle one, to illustrate this. The process of creation is the process of producing functionality from uselessness (represented in the cosmic waters, and the phrase tohu wabohu, “formless and void”). The making of heaven and earth is initially the designation of sacred space – ie defining the boundary of the temple courtyard. God creates the heavens and the earth.

There seems little doubt to me that Genesis 1 is, technically, a “temple inauguration text”, with the Cosmos as God’s “real” temple (of whose pattern the tent and Solomon’s building are imitations, Ex 25.40). Let’s use these pictures, especially the tabernacle one, to illustrate this. The process of creation is the process of producing functionality from uselessness (represented in the cosmic waters, and the phrase tohu wabohu, “formless and void”). The making of heaven and earth is initially the designation of sacred space – ie defining the boundary of the temple courtyard. God creates the heavens and the earth.

After the creation of light (or as Walton suggests, of time) God separates two spaces, the higher and lower heavens, by a raquia (= firmament = “something spread out”). The lower heaven is the sky, the atmosphere. The higher is God’s personal realm. You can see them in both pictures as the holy of holies and the sanctuary, separated by a curtain embroidered with spiritual “cherubim” and in the colours of the heavens (blue, purple and red). Or in the temple picture, this “firmament” is solid, of wood overlaid with gold – but still with its spiritual guardians.

The holy of holies contains the ark of the covenant, described in Scripture as God’s footstool, under the “mercy seat”. Israel’s elders are granted a visionary experience of God’s cosmic throne in Ex 24.9-11. Note that the pavement of this space is clear and blue “like heaven”, the name given to the firmament in Genesis 1. Note also that they have climbed Sinai, figuratively traversing the holy space of the sanctuary, the sky, to the holiest place.

Similarly note how in the temple and tabernacle both, the outer sanctuary is decorated with more cherubim, and also with the same sky colours, as if it were the bridge between God and his world.

The word firmament is itself interesting. Outside the creation account, it is rare, and is always used in relation to God’s glory rather than simply the physical sky. In Ps 19 it shows the handiwork of God, in parallel with the heavens, and in Ps 150 it is the “firmament of his power”. In Ezekiel’s strange vision of a kind of mobile spiritual sanctuary, a “firmament” is the base of God’s “chariot”, once more laid upon guardian cherubim who do God’s bidding on earth.

Back in Genesis, God next gathers the waters into one place – chaotic waters become the organised sea. Or in the temple picture, it becomes that large vessel of bronze, also called the “sea”. The sea is separated from the dry land – and in the temple picture we see it standing on its own in the courtyard where God’s people gather to worship.

Next God makes vegetation, which is represented in the palm trees and flowers decorating the sanctuary. The lights of Day 4 you can see in the menorah, whose 7 lamps represent the Spirit of God governing the earth, but also the sun, moon and 5 visible planets of the lower heavens – just God’s creatures, all, though vital to his economy.

Pillars are not mentioned in the Genesis account, and only creep into the modern idea of Hebrew cosmology through two (poetic) passages in Job. But Solomon’s temple has two, not supporting anything, least of all the sky, but symbolically named to represent God’s strength and faithfulness – he supports his own temple. They’re not found in the earlier tabernacle.

All temples have a divine image – and you can see representations of this in both pictures in the person of the priests. Their job is to serve God in his sanctuary and minister his blessing to the world, the selfsame role accorded to humanity bearing God’s image on Day 6 of the Genesis account. This will become particularly important in the next episode, when I will look at the Patristic view of cosmology.

Now for some general conclusions, apart from those already made in the previously linked post about the non-material and essentially spiritual vision of this cosmology – it is scarcely a cosmography except in the broadest sense of affirming that there is some correspondence between how God has ordered the Cosmos as his temple and the physical divisions of the world.

What we don’t see in either the tabernacle or temple pictures is God himself – for no man has ever seen God. But much is said about him by these pictures. Both the Israelite structures were conceived as being cleverly and beautifully contrived for God’s glory. Both in the Pentateuch and Kings/Chronicles the artists involved are named, and described as supremely skilled craftsmen, and in Exodus they are specifically said to be endowed with the Spirit of God. This is clearly because to make a worthy copy of God’s cosmic temple requires not only attention to “the pattern given on the mountain”, but the wisdom of God, who personally made the original with just as much skill and wisdom .

Every detail of the Cosmos (if the temple imagery is indeed a valid conclusion) must be crafted for its specific function in his worship. And though God is invisible, he was present in the shekinah (glory) of tabernacle and temple, and is therefore just as immanent in the cosmic original – he pervades all things in heaven and on earth.

The seventh day of creation, the Sabbath, as I’ve said on other occasions, represents God’s coming to dwell in his temple, analogously to the way he came to dwell in the tabernacle or the temple at their dedication (note incidentally that the temple building was a seven year process [1 Kings 6.38] culminating in a seven-day dedication and the Lord’s shekinah coming to fill the temple [2 Chron 7.9]).

Highest heaven cannot contain him, though that is his true dwelling, but the lower earthly sanctuary is indwelt by him too. So what does he do there? He keeps it in being and governs its activity, no less actually than the worshippers in the Israelite temple prayed for their daily needs, the well-being of their livestock, their government, the stability of the elements and so on at his hand. “My eyes and my heart,” says the Lord, “will always be there.”

Furthermore, in the biblical histories good kings were praised for their attention to the repair and ornamentation of the temple. In this they were only imitating God, the maker of the original temple, in his constant attention to the detail of its own order. So the cosmology of temple imagery suggests that God relates to each detail of the natural world he has created in the same way that he relates to Israel in their “religious” practice. He is transcendent and immanent in the physical universe as he is transcendant and immanent in the lives of his people. There is really no justification for a separation of “natural” and “supernatural” in this view, except insofar as God is the one supernatural being relating personally and intimately with all those things to which he has given natures.

Two significant things are missing from the cosmic temple that are present in the tabernacle. The first is any kind of hierarchy, either of humans (all men were created in God’s image) or of created things (although things are created for different roles, all relate to God directly and not through other creatures or spirits). Neither is there a sacrificial altar as there is so prominently in the courtyard of both tabernacle and Solomonic temple. Before sin, there was no need for atonement in creation to gain access to God – just for an altar for the incense of worship in his presence.

Both in the torah and in Jesus’s teaching the presence of God made the temple, the altar and the priests holy, though they were ontologically earthly things. That kind of immanence brought a shine to Moses’s face, death to those who touched the ark and destruction to the temple when God’s presence departed. The whole world is seen by the Bible writers to be like that: a material artifact made by God but suffused by his presence. That is a far more dynamic cosmology than the quaint conceits of the first illustration above.

Next time I’ll try to show how the eary theologians of the Church remained faithful to that cosmology, and refined it in the light of Christ.

I wonder if some future people found ruins with our common language used in coding and the invisible world of information transfer, whether they’d think we were primative and think there was some hidden world. Or even how the German philosophers and poets would speak of the noumenal, or a world of ideas. Were they just idiots who misconceived the world?

I wonder if we’re just dull in thinking the ancients were so completely stupid. NT Wright has done a great job, in modern biblical scholarship, to show the contrary. I love how some modern people will scoff about the ethical opinions of goatherds 3000 years ago, yet do they know how the house they live in was constructed? Yet they mock those who built the pyramids, which is still not quite known on how.

I suppose ultimately, though, even this will become a chicken or egg argument. Did the Hebrews build their Temple based upon revelation of God’s creation? Or did they Hebrew take their temple form, accumulated over time, and project it upwards and made their own god look like them? This can be parsed through, but ultimately I guess it depends on the spectacles you choose(?) to wear. Do you rule out ‘Deus dixit’ and just chalk it up to grand imagination? But I suppose we’re all working, in our own trusts, from fides quarens intellectum.

Another thought:

I wonder if we can speak of prayer and even the Supper as sacrifice, given the consideration that not all sacrifices are towards atonement (i.e. the incense . The eucharist echoes the once and for all Atonement, but is a sacrifice of thanksgiving and fellowship, an eschatological echo of the eternal feast. I wonder if this is what the early Church had in mind when they used the language of ‘thanksgiving’ and ‘sacrifice’ without implying Roman judaizing.

Cal

Did the Hebrews build their Temple based upon revelation of God’s creation? Or did they Hebrew take their temple form, accumulated over time, and project it upwards and made their own god look like them?

As you suggest, Cal, it’s a matter of faith whether it came from God or man. But I’m writing for Evangelical Christians to persuade them that’s what the Bible says, rather than to convince Stephen Hawking what a good cosmology they had.

But assuming inspiration, we read that the pattern of the tabernacle was revealed, and the pattern commanded to be followed. It corresponded to some heavenly reality. As I wrote in the previously linked post, I think it’s a two way street – the tabernacle is inspired by cosmology, and the cosmology is like the temple. In both cases the same theological truths are being stated – we learn what the world and people are in relation to God.

The Eucharist is indeed a thanksgiving (hence the name), but I wouldn’t want to speculate on whether it’s represented in the cosmic temple! My twopenn’orth is that Christ’s presence in the highest heaven is the conbtinuing intercession for us mentioned in the NT.

However, you’ll perhaps recall that in Revelation (which is largely built on the imagery of God’s cosmic temple), bowls of incense represent the prayers of the saints.

The questions were mostly rhetorical, which throws the question down to certain trusts we all possess. Whether we’re atheists or Chrstians, we’re operating from the same principle of faith seeking understanding. Whether we believe in the Logos Incarnate in Jesus of Nazareth, or an endless multiverse.

Well, I wonder whether the Wedding Feast of the Lamb is that eschatological reality of the Eucharist, which is a mere token (perhaps represented in the token bread and wine we take in our corporate worship). Indeed, prayers also represent a sacrifice, and sometimes they really are sacrificial (when involving sweat and tears)!

Cal