In the last post I showed how “probablistic chance” fares no better than “Epicurean chance” as a true cause of physical events. Half of Monod’s materialistic “chance and necessity” explanation for evolution thereby falls to the ground. What is left is what appears to be the safer concept of nature obeying the “laws of nature” (ie the natural truths behind the formulations scientists make). This necessity, we assume, is a commonplace foundation of science which fits well into the theistic framework: God writes the laws of nature, and so achieves his purposes in the world.

But the overview article (a must-read) I linked to last time, by Norman Swartz, who trained as a physicist before becoming an historian and philosopher of science, shows just how fragile the concept of laws of nature is on close examintation.

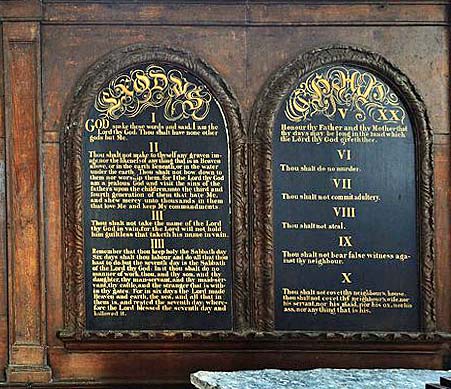

As I’ve pointed out in the past, the scientific idea of “law” was the attempt of Baconian science to universalise order in an atomistic, passive universe, against Aristotle’s concept of individual “natures”, by a direct transfer of the concept of an unbreakable Mosaic law to nature (Scripture itself having no such concept). Sinful humans could break the law of Moses – passive nature was bound by God’s decrees. This actually arose, in the first place, from a misunderstanding of the role of the Mosaic law as a binding code rather than as a demonstration and paradigm of God’s judicial wisdom (cf John Walton in The Lost World of Scripture for this). But even considered in a theistic context, Swartz points out how problematic this is:

As I’ve pointed out in the past, the scientific idea of “law” was the attempt of Baconian science to universalise order in an atomistic, passive universe, against Aristotle’s concept of individual “natures”, by a direct transfer of the concept of an unbreakable Mosaic law to nature (Scripture itself having no such concept). Sinful humans could break the law of Moses – passive nature was bound by God’s decrees. This actually arose, in the first place, from a misunderstanding of the role of the Mosaic law as a binding code rather than as a demonstration and paradigm of God’s judicial wisdom (cf John Walton in The Lost World of Scripture for this). But even considered in a theistic context, Swartz points out how problematic this is:

Religious skeptics … might have wondered why (/how) the world molds itself to God’s will. God, on the Prescriptivist view of Laws of Nature, commanded the world to be certain ways, e.g. it was God’s will (a law of nature that He laid down) that all electrons should have a charge of -1.6 x 10-19 Coulombs. But how is all of this supposed to play out? How, exactly, is it that electrons do have this particular charge? It is a mighty strange, and unempirical, science that ultimately rests on an unintelligible power of a/the deity.

I’ll return to that “unintelligibility” later – Swartz is right in implying that, in the end, science cannot escape from a final cause beyond itself. But he’s also right in saying that the idea provides no explanation for how God would apply his laws, unless in some occasionalist sense of doing everything himself. Remove God from the picture, and the idea that that laws of nature are prescriptive is even less coherent:

Twentieth-century Necessitarianism has dropped God from its picture of the world. Physical necessity has assumed God’s role: the universe conforms to (the dictates of? / the secret, hidden, force of? / the inexplicable mystical power of?) physical laws. God does not ‘drive’ the universe; physical laws do.

But how? How could such a thing be possible? The very posit lies beyond (far beyond) the ability of science to uncover. It is the transmuted remnant of a supernatural theory, one which science, emphatically, does not need…

The problem is this: a law is an immaterial, often mathematical concept. The Decalogue was enshrined in torah on hearts and minds, and enshrined on tablets of stone. But where are these laws of nature supposed to reside? And how is inert matter supposed to “know” that it must obey these abstract decrees? Nobody has ever been able to answer this satisfactorily:

Some recent authors [e.g. Armstrong and Carroll] have written books attempting to explicate the concept of nomicity. But they confess to being unable to explicate the concept, and they ultimately resort to treating it as an unanalyzable base on which to erect a theory of physical lawfulness.

In other words, there is no viable explanation, but it must be true if the laws are binding on the universe. But as a matter of empirical science, there is no justification for the last assertion. The most that science can say (as Hume pointed out) is that we are able to observe certain patterns in nature every time we look carefully enough, and that it is practically useful to assume that such patterns will apply universally in time and space, and to work on the basis that they are therefore “necessary”. Swartz points out the logical weakness in this:

Necessitarians – unwittingly perhaps – turn the semantic theory of truth on its head. Instead of having propositions taking their truth from the way the world is, they argue that certain propositions – namely the laws of nature – impose truth on the world.

The Tarskian truth-making relation is between events or state-of-affairs on the one hand and properties of abstract entities (propositions) on the other. As difficult as it may be to absorb such a concept, it is far more difficult to view a truth-making relationship the ‘other way round’. Necessitarianism requires that one imagine that a certain privileged class of propositions impose their truth on events and states of affairs. Not only is this monumental oddity of Necessitarianism hardly ever noticed, no one – so far as I know – has ever tried to offer a theory as to its nature.

So in this case, observation of the effects of regular true causes leads to a deduction of propositions called “laws”, which are then illegitimately held to necessitate the very causes from which they are derived. Now, notice how similar this is to the error to which I drew attention in the last post in considering probability as a cause in nature, when it is in fact an effect of true causes:

Necessitarians, however, frequently have severe problems in accommodating the notion of statistical laws of nature. What sort of metaphysical ‘mechanism’ could manifest itself in statistical generalities? Could there be such a thing as stochastic nomicity? Popper grappled with this problem and proposed what he came to call “the propensity theory of probability”. On his view, each radium atom, for example, would have its “own”(?) 50% propensity to decay within the next 1,600 years. Popper really did see the problem that statistical laws pose for Necessitarianism, but his solution has won few, if any, other subscribers. To Regularists, such solutions appear as evidence of the unworkability and the dispensability of Necessitarianism. They are the sure sign of a theory that is very much in trouble.

There’s a lot of fuss over the claim that Darwinian evolution is a theory in deep trouble – but perhaps the real attention should be on the far graver issue that the idea of prescriptive laws of nature is impossible to sustain coherently:

A number of Necessitarians (see, for example, von Wright) have tried to describe experiments whose outcomes would justify a belief in physical necessity. But these thought-experiments are impotent. At best – as Hume clearly had seen – any such experiment could show no more than a pervasive regularity in nature; none could demonstrate that such a regularity flowed from an underlying necessity.

This much I have discussed before over the years. I had not previously realised, though, that this issue is represented by a deep divide amongst philosophers of science, the “Necessitarians” being opposed by a large body of “Regularists”, who more modestly restrict themselves to “laws of nature” as mere descriptions of the way the world is, without attempting to explain why it is thus by invoking necessity.

On the Regularists’ view… It’s true that you cannot “violate” a law of nature, but that’s not because the laws of nature ‘force’ you to behave in some certain way. It is rather that whatever you do, there is a true description of what you have done. You certainly don’t get to choose the laws that describe the charge on an electron or the properties of hydrogen and oxygen that explain their combining to form water. But you do get to choose a great many other laws. How do you do that? Simply by doing whatever you do in fact do.

As Swartz points out, this idea neatly dissolves even intractable problems like free will – when you choose, you establish a proposition just as true as, if less universal than, the law of gravity. Immediately, we sense that the explanation of scientific regularity is avoided by Regularists simply by being ignored. But in fact, what is happening is a careful, and important, drawing of boundaries around the explanatory power of science – it’s the refusal to allow science to pretend to answer metaphysical questions beyond its competence. In other words, it’s the denial of the scientism which BioLogos, for example, officially rejects. But it’s a denial in fact, rather than merely paying lip-service whilst retaining many scientistic assumptions (“soft scientism”), including the assumption of the binding nature of laws of nature.

But for Necessitarians, the way-the-world-is cannot be the rock bottom. For after all – they will insist – there has to be some reason, some explanation, why the world is as it is and is not some other way. It can’t simply be, for example, that all electrons, the trillions upon trillions of them, just happen to all bear the identical electrical charge as one another – that would be a cosmic coincidence of an unimaginable improbability…

Regularists will retort that the supposed explanatory advantage of Necessitarianism is illusory. Physical necessity – nomicity if you will – is as idle and unempirical a notion as was Locke’s posit of a material substratum. Locke’s notion fell into deserved disuse simply because it did no useful work in science. It was a superfluous notion…

At some point explanations must come to an end. Regularists place that stopping point at the way-the-world-is. Necessitarians place it one, inaccessible, step beyond, at the way-the-world-must-be.

Now, as foundations for secular science (that is, the science of methodological naturalism) Swartz shows that Necessitarianism and Regularism are mutually exclusive and formative for ones whole view of the world:

The divide between Necessitarians and Regularists remains as deep as any in philosophy. Neither side has conceived a theory which accommodates all our familiar, and deeply rooted, historically-informed beliefs about the nature of the world. To adopt either theory is to give up one or more strong beliefs about the nature of the world. And there simply do not seem to be any other theories in the offing. While these two theories are clearly logical contraries, they are – for the foreseeable future – also exhaustive of the alternatives.

But Swartz has quietly excluded a theistic understanding in this somewhat pessimistic analysis – he has thrown out a philosophically unjustifiable necessitarianism whilst retaining a philosophically unjustifiable naturalism. Can the metaphysical acceptance of God, perhaps, break the intellectual log jam (albeit by admitting the ultimate mystery of Deity)? Remember how Swartz expressed the problem with prescriptive laws even in their original theistic context:

But how is all of this supposed to play out? How, exactly, is it that electrons do have this particular charge? It is a mighty strange, and unempirical, science that ultimately rests on an unintelligible power of a/the deity.

In describing Necessitarianism, he describes two varieties. The first is the familiar (and probably incoherent) one of abstract laws mystically influencing entirely passive particles. The second is a more Aristotelian view that regularities are part of the natures of individual entities – so that the charge of an electron is a feature of its individual nature, rather than an external “abstract truth” imposed upon it. Both varieties are vulnerable to his fundamental critique of Necessitarianism, but the second, it seems to me, avoids the problem of mystical prescriptive laws existing nebulously within the universe.

Assuming a naturalistic science, a science of natures appears to be less satisfactory than a set of universal rules governing the whole universe – though as we have seen, such  universals cannot be intelligibly conceived. But once one admits the Creator, the existence of a “design concept”, or form, applied to each and every electron created in the universe, is not problematic at all. Even humans mass-produce basic components – and there are, as we know, very good reasons at the theological level for God to be the Creator of regularity as well as the Creator of contingency. He is both faithful and innovative, and the regularity of the universe reflects his faithfulness.

universals cannot be intelligibly conceived. But once one admits the Creator, the existence of a “design concept”, or form, applied to each and every electron created in the universe, is not problematic at all. Even humans mass-produce basic components – and there are, as we know, very good reasons at the theological level for God to be the Creator of regularity as well as the Creator of contingency. He is both faithful and innovative, and the regularity of the universe reflects his faithfulness.

Such a view doesn’t explain how God creates electrons or anything else, but that only matters if one insists that science has to explain the Deity’s acts, rather than perform its proper, more limited, role of explaining how what God creates interacts. “God created the natures of electrons with this particular charge” is certainly inexplicable in terms of material efficient causation, but so is the proposition “God created a universe which began 14+ billion years ago.” The creation of God is the logical place for the believer to stop looking for efficient causes: but the unbeliever too can look no further and remain a scientist.

Removing the philosophically unjustifiable principle of necessity arising from laws of nature deals the death blow to the ability of Monod’s “chance and necessity” to explain anything about evolution. Neither chance nor necessity are meaningful terms in themselves. It also, incidentally, removes any justification for thinking of the universe as a closed system, whose laws bind God’s activity as much as they bind material processes. As Alvin Plantinga has well argued, God is free to make his universe rigidly regular, approximately regular, usually regular or anything in between.

Removing the philosophically unjustifiable principle of necessity arising from laws of nature deals the death blow to the ability of Monod’s “chance and necessity” to explain anything about evolution. Neither chance nor necessity are meaningful terms in themselves. It also, incidentally, removes any justification for thinking of the universe as a closed system, whose laws bind God’s activity as much as they bind material processes. As Alvin Plantinga has well argued, God is free to make his universe rigidly regular, approximately regular, usually regular or anything in between.

But that does not matter in considering how science operates, particularly in understanding evolution and origins. Science, with its epistemological limitations, would still operate as well as it does, provided God has provided regularity, as he undoubtedly has. Secondary causes, as a matter of empirical observation, create repeatable patterns from which we can derive true propositions. To paraphrase Swartz in Regularist mode: “Whatever nature does, there is a true description of what it has done.” In many cases we can connect those true propositions in terms of chains of efficient material causation, and as we do so our knowledge will grow. We can even connect them in terms of empirically-determined statistical probabilities, and make duly approximate predictions accordingly. Science continues to uncover truth about the world.

But we will, to my mind, achieve a much clearer idea of where science must stop, and where the supra-scientific creative power of the Logos must be admitted, by dethroning both “chance” and “necessity” as causative powers. Physical and chemical forces are true causes. Physiological mechanism are true causes. Created teleological processes, such as human minds, are true causes. And God is the final true cause of them all, and the only providential Governor of them all.

By the way – the derivation of the title of this piece is from this: