One of the strands running through some of these posts is that if we want to understand God’s ways in creation (and therefore scientific questions like evolution), we must also understand how he acts now. I’m speaking here as to Christians, who accept Scripture’s inspiration and authority, but who sometimes say these questions of God’s governance in the world are moot. The same (they say) is therefore true of God’s involvement in natural processes and the vexed question of natural evil.

There seems to be a feeling that the kind of philosophical-theological views proposed in such concepts as concurrentism are imposed upon the biblical text. But I’m going to argue that in many or most cases they are necessitated by that text itself.

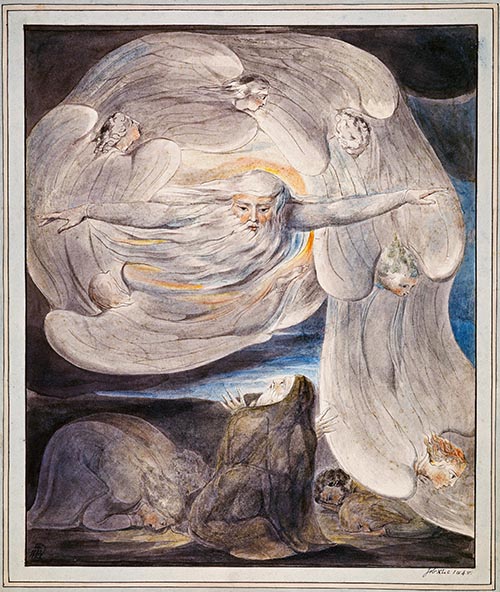

I want to refer to the book of Job, described by Alfred Tennyson as “…the greatest poem, whether of ancient or modern literature.” I’d concur with that, but also add that it’s perhaps the greatest exposition of God’s relationship to creation and to moral and natural evil I know. Job has been dated everywhere from the time of Moses to that of Ezra – but what cannot be doubted is that it precedes by many centuries the scholastic philosophers’ struggle with the deep truths of God.

Yet it is in its own way just such a philosophical treatise, though an inspired one. I want only to focus on one small aspect here – don’t assume I’m saying it’s all the book can teach us. Job, and his sufferings, may or may not have existed. But this is one case where it is not only irrelevant to its truth, but where strict historicity would actually weaken the argument. Job is set up as a test case, on which to discuss the issue of God’s righteousness and innocent suffering – just the kind of theodical agenda beloved of modern theologians of creation. One mark of this is the way in which Job and his disputants focus entirely on the meaning of Job’s own suffering, whereas in a real situation, concern for the deserts and fate of his dead children and servants would complicate the matter.

So Job is the quintessential righteous and blessed man, and the inspired narrator does not have to guess at his inner life – or even at the affairs of heaven. We know that Satan – who as a member of the angelic divine council seems to play an quasi-offical role as accuser – seeks to expose the falsity of Job’s faith. Maybe that’s from malice, but we’re not actually told that. God contends his faith is real and actively permits, and limits, his tribulations.

Even on The Hump believers have expressed moral qualms about the kind of God who would make such a “bet” – but in fact, such motivational issues are the whole point of the book, as the detail here will show. We can see that God intends, in the end, to vindicate and bless Job, but that too is not stated explicitly because God refuses to explain his actions.

What is most interesting is that neither Job nor his interlocutors attribute any of Job’s problems to Satan – even though we must suppose he was no less a part of their theology than of the author’s. Universally they attribute his sufferings only to God – and that includes the narrator. My focus is on two early statements of this. In 1.21, after all his children and property are trashed, Job says:

“The Lord gives and the Lord has taken away; may the name of the Lord be praised.”

The narrator’s response is:

In all this Job did not sin by charging God with wrongdoing.

This is all the more remarkable when one looks at what had happened: no less than two sets of human raiders had, no doubt from morally evil motives, engaged in theft and murder: actual evil had occurred. The natural world was involved too, in the form of a sudden wind and “the fire of God”. The latter term is, perhaps, a colloquialism for “lightning”, but even if so shows its close mental connection in Hebrew minds with God’s personal action.

But Job’s innocence is not in denying God’s involvement in the human sins or the natural evils, but rather in bypassing these altogether as mere secondary causes, attributing all the losses to God, and yet not charging God with wrongdoing.

The second example is like unto it. In 2.10, after Job himself is medically afflicted and his wife invites him to curse God, he again is explicitly said not to sin in his response… which is is to rebuke his wife and say:

“Shall we accept good from God, and not trouble?”

Once again, the narrator asserts that:

In all this, Job did not sin in what he said.

We who are in the know are aware of Satan’s agency here, but it is ultimately irrelevant to Job, to the narrator and to the whole ensuing debate. For example, Eliphaz in 5.17 argues:

“Blessed is the man whom God corrects; so do not despise the discipline of the Almighty [cf Heb 12]. For he wounds, but he also binds up; he injures, but his hands also heal.”

And though Job disputes that his life warranted such “correction”, he agrees with its source in 6.4:

“The arrows of the Almighty are in me, my spirit drinks in their poison.”

What we see here is a sophisticated, and uniquely Yahwist, understanding of concurrentism which, if taken seriously, leads almost inevitably to the kind of scholastic ideas I dealt with in previous posts. There is no doubt in the author’s mind that the Sabeans and Chaldeans did culpable evil. They were incited (somehow) to it by Satan’s agency. But the ultimate cause of it (to the extent that all these secondary causes are dismissed as irrelevant) is the Lord himself. And yet the book is adamant that God is guilty of no wrongdoing. Clearly God is willing (as primary cause) certain events to some ultimate good – in this case, Job’s understanding and blessing – though there is genuinely culpable evil volition involved in both Satanic and human outworking of those events. God wills for good what others concurrently will for evil.

We are not permitted to see clearly what God’s purposes were – they included the victory of Job’s faith over Satan’s accusation, and the vindication of God too, as well as the final blessing of the protagonist – but nothing whatever is said about the collateral damage to Job’s family and servants, whose purpose remains hidden in God. The message of the theophany at the end of the book is that God is simply not the sort of Being who can be questioned in that way.

Applied to “natural evil” the argument is parallel. God (ultimately) sent the lightning, hurricane and boils, for the same good, but largely hidden, ends as the actions of the evil raiders. The elements themselves were not morally evil. But neither were they the least bit autonomous.

Job would have been sinful, the book says from start to finish, to attribute wrongdoing to God. But it’s corresponingly clear that he was right to attribute the events themselves to God. It would, indeed, have been an equal calumny on God to deny his wrongdoing by denying his active sovereignty over the actions of nature, humans and even Satan himself.

Compare that to the attitudes within theistic evolution. For example, consider Francisco Ayala’s claim that to attribute poor design or morally questionable animal lifestyles to God’s design is “blasphemous”. Consider the whole new theology of nature mentioned in my last post, in which God must be distanced from the cruelty and waste in creation by its autonomy, connecting to it only by his suffering on its behalf.

Now from those viewpoints, Job’s whole attitude is scurrilous and anti-Christian. He’s so stupid as to fail to realise that he has made out God to be a moral tyrant by not distancing him from evil, and the writer of Job is just as blind and insensitive… even though such matters were the entire substance of his meditation under the guidance of the Spirit of Christ.

So it seems there is even nowadays a debate between Job and some of his believing friends in the TE movement. Is the matter doomed to remain unsettled, or perhaps to be decided by the superiority of the new theology in the light of scientific knowledge? Maybe, but there’s an alternative interpretation in the book of Job itself.

God speaks in the final chapter:

“I am angry with you and your two friends, because you have not spoken of me what is right, as my servant Job has. So now take seven bulls and seven rams and go to my servant Job and sacrifice a burnt offering for yourselves. My servant Job will pray for you, and I will accept his prayer and not deal with you according to your folly. You have not spoken of me what is right, as my servant Job has.”

And wonder of wonders – that’s exactly what they did.

I tend to think of the Book of Job as the ancients reacting to a prophecy about Jesus. They (I hypothesize) were told that there would be man who would be subject to many unpleasant events, and that these events were necessary for a Good Reason. That reason — the glorification — required that Jesus would always resist these temptations, including the temptation to blame God for them. Even though God instigated the birth of Jesus, both knowing that Jesus would necessarily be subject to all these things.

The ancients must have wondered whether any man could be that sufficiently perfect! So they wrote “Job” about this possibility, to them at first just imagined. To them, a fantastic story. But one, they were told, that would come true.

I realize, though, that this idea I just stated does not exactly support your argument. You appear to want that any Christian can reasonably take the attitude of Job: that no matter what comes to us from God and however good or bad, God is never doing anything wrong.

Or maybe we can take that approach, after all? Not easy, but possible.

Ian

The main thrust of my article is tangential to the interpretation of the main part of the book – the debate about innocent suffering and Job’s theophany and vindication. I focused really on the writer’s view on what kind of God was behind the scenario portrayed, ie one who governs all events in the world for good, even when they seem to be evil (or even when they are undoubtedly evil, in the case of men’s evil deeds).

The closest “challengable” issue, it seems to me, is whether that God’s actions are often inscrutable, and their goodness must be taken on trust rather than being explicable. Even if the story is in some way about the sufferings of Jesus, that point is still valid: one could usefully use the book to show that the apparent guilt of Jesus in being punished by God on a tree is because of a hidden, good, divine purpose – perhaps it’s a good apologetics text for the Jew or Muslim who stumbles at the cross. And that’s true, but Job itself still leaves God’s purposes hidden: Job never even finds out about the contest with Satan. So, does God have inscrutable purposes only comprehensible in the future, if then? Yes.

I’d argue that your christological interpretation is unnecessarily speculative, though. Nothing in the text suggests it, and the question of unjust suffering was a necessary theological balance to the general position (of, say, Proverbs) that the world is governed justly, and that evil doesn’t prosper and it’s worthwile being righteous. Job’s friends all assume it to be a universal principle, and assume its broad converse – that suffering implies just deserts. In that context, Job doesn’t need to be seen as sinless – he even admits to his sins in the debate – but as being “righteous” in the sense of upright and godly, ie the guy for whom Proverbs expects blessing rather than – as in Job’s case – a complete life meltdown.

Like Ecclesiastes, it’s immensely sophisticated wisdom literature. I’ve found Job pastorally invaluable – especially in the medical context. It’s the antodote both to trite piety (“I expect I’ve got this painful disease because I’ve been faithless/because God wants to teach me a [or any other justification snatched from the air]”) and despair (“God can’t really care about me or he’d never let me/mine suffer.”) Such situations are real, indeed common, and not only Job, but scattered scriptures elsewhere, show that the Bible’s position is consistently that God is good, just, loving and wise – but his ways are higher than ours.

He is the source of all goodness, not a person whose goodness can be judged against the goodness we assess in ourselves and other persons… which takes us back to the theistic personalism discussed on the inspiration thread.

One real new revelation in Christ is that God’s concern about our suffering is spelled out in the blood of his Son, and that we can also see in the glorification of Christ following unjust suffering the paradigm for believing that God will also right all other such apparent wrongs.