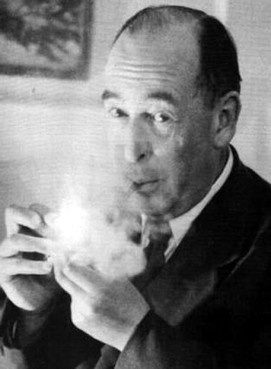

When I cited Os Guinness in a recent post, I noticed a reference to an important essay by C S Lewis whilst re-reading Guinness’s assessment of humanism. It’s well worth reading, though from the 1940s, and gives that feeling you always get with Lewis that, although a mediaevalist, he was half a century ahead of his time.

As you’ll rapidly appreciate, reading the piece, he is pronouncing a eulogy for the popular myth of evolutionism, which he distinguishes carefully from the biological theory of evolution. I found it interesting that he refers to this myth as “Wellsianity”, since I used the film of H G Wells’ Things to Come as the focus of a blog on a similar theme a couple of years ago.

Let me draw attention to a couple of things in this essay. Firstly note the demonstration he gives that popular evolutionism predates Darwin’s theory by several decades, at least. Typically Lewis establishes this via literary quotations, but it has also been shown by the historical fact that, whilst the scientific guild were quite slow to accept Darwin’s theory, the Origin of Species became a best-seller through its popularity with what we should now call “the chattering classes.”

Even Darwin himself was plagued by the “progress” mythology, for though undoubtedly he was part of the society that was longing for a theory of progress, and personally committed to naturalism, he was also after a true biological theory and only reluctantly came to accept the “evolution” terminology of Spencer, whom he actually despised. At the same time I suspect Darwin knew enough about what would sell the theory, and he put in several purple passages about the perfecting wisdom of natural selection, even though the Origin shows a clear awareness of evolution’s capacity to produce “degeneration” as well as “progress”.

Lewis’s essay is fascinating, though, in showing the bearing of cultural setting and mythology on scientific theory. They were mutually reinforcing:

Almost before the scientists spoke, certainly before they spoke clearly, imagination was ripe for it…

The prophetic soul of “the big world” was already pregnant with the Myth: if science had not met the imaginative need, science would not have been so popular. But probably every age gets, within certain limits, the science it desires.

I’ve pointed out in the past S J Gould’s not entirely tongue-in-cheek suggestion that his own punctuated equilibrium theory might simply be the product of a science beginning to prefer catastrophism again, rather than a closer approach to truth. Gould thought more deeply than most. So did Lewis, who observes that mythical evolutionism became the explanation for everything:

To those brought up on the Myth nothing seems more normal, more natural, more plausible, than that chaos should turn to order, death into life, ignorance into knowledge.

Historically that is so astute – apart from the Teilhard de Chardins of the world turning evolution into an entire eschatological theology, more mundane theology became evolutionary through higher criticism. Anthropology became evolutionary via eugenics and scientific racism, and politics via communism, imperialism and later, Fascism. Economics began to look to endless growth, wealth and leisure, medicine to the cure of all ills, technology to the conquest of the whole earth and then the Universe…

Those of us brought up even much later than this essay will remember how our lives were full of visions of the bright future that science, technology – and evolution – would bring. One of my first serious ambitions was to be the first man on Mars: the future was that imminent.

Lewis, though, reading the runes in the new literature of his time, saw an end in sight. The myth was dying. And looking at western society as a whole, has not his prediction come true? What bright future do politicians now see? After a corrupt and disastrous attempt to impose democracy across the world, it seems that everyone’s keeping as quiet as possible whilst nations fall to militant Islam, too lacking in their own vision even to wring their hands. Workers are becoming used to the reality that their wealth will decrease whilst a few become super-rich – they lack the energy even for revolution. Medicine is about antibiotic resistance and spiralling costs (with rationing!), and the future of the world doesn’t stretch much beyond the inevitable Armageddon of global warming – that’s too close to home to have the same heroic ring as the universal heat-death Lewis alludes to.

It does seem that, as a compass for western society, the Myth has lost most of its magnetism. The public is herded along in the welter of progressive ethical and moral changes, without any real sign that it believes there will be a better world as a result. Hope in progress is nowadays in short supply. To the extent that anyone understands postmodernism, it’s seen as bringing unavoidable, rather than welcome, change.

I’m amazed at how, over half a century before Plantinga or Nagel, Lewis puts his finger on the fatal flaw of evolutionary myth – which of course is also the fatal flaw of naturalistic materialism:

What makes it impossible that it should be true is not so much the lack of evidence for this or that scene in the drama or the fatal self-contradiction which runs right through it. The Myth cannot even get going without accepting a good deal from the real sciences. And the real sciences cannot be accepted for a moment unless rational inferences are valid: for every science claims to be a series of inferences from observed facts. It is only by such inferences that you can reach your nebulae and protoplasm and dinosaurs and sub-men and cave-men at all. Unless you start by believing that reality in the remotest space and the remotest time rigidly obeys the laws of logic, you can have no ground for believing in any astronomy, any biology, any paleontology, any archeology. To reach the positions held by the real scientists–which are taken over by the Myth–you must, in fact, treat reason as an absolute. But at the same time the Myth asks me to believe that reason is simply the unforeseen and unintended by-product of a mindless process at one stage of its endless and aimless becoming. The content of the Myth thus knocks from under me the only ground on which I could possibly believe the Myth to be true.

Note how Lewis makes a single exception to the proper separation of scientists from evolutionary myth in the instance of Prof D D M Watson, and concludes:

This would mean that the sole ground for believing [evolution] is not empirical but metaphysical – the dogma of an amateur metaphysician who finds “special creation” incredible.

“But I do not think it has really come to that.” He adds. And I found myself wondering whether that was one point at which Lewis had misjudged the issue. Whatever may have been true in Lewis’s time, can it really be said that the scientific establishment – and especially its biological arm – has been successful in keeping “amateur metaphysics” out of its evolutionary science? In fact, is there not some evidence that the one part of society in which the myth of progress is alive and well is in some parts of the scientific community?

Whether it’s in the quest for extraterrestrial life, in transhumanism (and even in lesser technologies like GM food), in the enthusiastic quest to put morality on a “scientific” or evolutionary footing, in the rooting out of religious superstition by any and all means, or even just the plaintive pleas of those like Peter Atkins that the people should begin to taste the bracing ozone of their insignificance in the universe, it seems that the pull of the future is felt mainly by spokesmen for science, whilst the broad masses drag their feet and begrudge the megabucks of funding for particle accelerators and Mars missions… or if they’re in the appropriate demographic, they dig their heels in for Creationism or go off to fight for a Caliphate in Syria. The past is the new future.

I understand that later in life Lewis became much less convinced that the separation of science and mythical evolutionism was as real as he painted it in this essay. Maybe he was right, in that Watson’s quote seems of a piece with much of today’s zeitgeist in the origins discussion.

Whether or not that is so, though, Lewis’s final paragraph is a word to Christians in this generation. He wrote in code, it is true, but as a Christian apologist. Then, as now, the authentic gospel was counter-cultural, bringing de-mystification, but also true rationality, as it challenges whatever comforting illusions the times bring. Maybe now the illusions are far less comforting, and more akin to the stupor of a hard drug taken too regularly. But Lewis is still on the mark when he writes:

We must not fancy that we are securing the modern world from something grim and dry, something that starves the soul. The contrary is the truth. It is our painful duty to wake the world from an enchantment. The real universe is probably in many respects less poetical, certainly less tidy and unified, than they had supposed. Man’s role in it is less heroic. The danger that really hangs over him is perhaps entirely lacking in true tragic dignity. It is only in the last resort, and after all lesser poetries have been renounced and imagination sternly subjected to intellect, that we shall be able to offer them any compensation for what we intend to take away from them.

I just finished rereading Lewis’ essays collected under the title “Abolition of Man” which (without actually checking dates) I am going to guess that he wrote in years prior to his “Funeral” essay you link here. (Thanks for this, by the way!)

In his Abolition talk, he follows man’s conquest of nature to its logical end (culminating ironically in nature’s final conquest of man), whereas in this essay he seems to recognize that such a thing is mythical and beginning to be recognized as such.

I may be way off in this as I have yet to grasp (much less fully grasp) all the depths of his ideas.

What Lewis writes in “Abolition” of the Tao (whatever we take as our axiomatic grounding or first principles for all subsequent values) and the fatality of our thinking we can step outside of that is, I think, brilliant and also at least as applicable now as it ever has been.

Hi Merv

Thanks for comment. As I (vaguely) remember the Abolition of Man its target is mainly logical positivism as such, with particular emphasis on the denial of man’s innate moral sense (which is what he calls “the Tao”).

That’s implicit in this essay, but I think his outworking of it in the myth of progress is a slightly different emphasis… maybe partly because the latter is/was a popular conceit, rather than the more or less conscious philosophy held by the villains of “Abolition.” That’s less a “myth” than just a stunted intellectual position.

The net result seems the same, in the end.

The “deceased” which is the subject of Lewis’ funeral oration in this case was still kicking at least in my own childhood years, and to that extent still affects my generation’s outlooks from our childhood memories at least.

I remember a sort of unbridled optimism that my dad and his generation seemed to have about everything just improving –we kids would of course be surpassing everything our parents achieved in education (which many of us did) and would be wealthier than our parents just as they became wealthier than theirs (not nearly so many of my generation are on that track anymore). But the optimism was definitely there which perhaps only feeds the disillusionment now.

It surely isn’t a fair comparison in terms of magnitude or tragedy, but perhaps our awakening to the inherent impotence of science and technology to (by themselves) ensure perpetual progress is to us today — perhaps all that is to us what World War I was to the notion of eternal human progress via perfected political systems (and science) a century ago.

Yet Lewis was right …. it still haunts our dreams and may even motivate our agendas still. If we would just tweak that a little … and a little more education there …

Yes – I thought when I first read the essay that he’d announced the funeral prematurely, but then saw how he saw that old stories live on even when they’re losing their power. It’s a similar phenomenon to the period leading to a scientific paradigm shift – geocentrism remains plausible to many even when the evidence base has shifted. The old gods still owned the temples even when the people only believed in them for comfort.

I’d thought of mentioning the disillusion of World War 1 in the post, but it would have overcomplicated matters. The “roaring twenties” were, I guess, a kind of “eat, drink and be merry” blanking of the future. Yet somehow not only faith in science but faith in some new politics (eg Communism, Naziism) for a while replaced the old certainties.

That slow attrition was why I’ve always liked Os Guinness’s phrase “The Striptease of Humanism” (though reading his chapter reminded me he nicked the phrase from Sartre).

Why does Lewis have such a hold on religious people? I sincerely can’t understand the appeal. Maybe it is because he so eloquently encapsulates their own prejudices. His line “Unless you start by believing that reality in the remotest space and the remotest time rigidly obeys the laws of logic, you can have no ground for believing in any astronomy, any biology, any paleontology, any archeology” is poetic nonsense, for the reasons I gave in the previous two posts. The ability of science to predict the behavior of the world is not the result of any assumptions about how reality behaves. Reality could have been otherwise. It could have had magical elements that were not describable by scientific laws. Under certain circumstances, these elements could be detected. Laws might regularly be violated by magical spells or prayers, and if these were strong enough, their effect could be detected. Their non-detection, and the success of the math in describing and predicting so much, is an empirical observation.

Now it is true that the success of our theoretical descriptions, in physics especially, is so overwhelming that it would take quite a bit of evidence to convince us that this magic-free view is false. But it is not something we have assumed from the beginning. Indeed, as you all know, some of the inventors of the mathematics underlying science (eg Newton) did believe in magic. They did not assume their equations were universally true. According to Lewis, Newton would have had no grounds for believing that his equations captured some aspect of reality. But he applied them to some problems, and they worked. This meant the equations did capture something of the essence of reality, if only approximately. Newton still thought magic tweaks might be needed, but later scientists found out that we never actually needed the magic tweaks.

Lou, the reason so many Christians rate Lewis is that they take the time and effort to understand what he’s actually saying. If you don’t get the argument coming from him, you’re evidently overdue to read the same thing from an atheist like Thomas Nagel. Lewis is talking about the inability of materialism to account for reason (and therefore to justify relying on it rather than equally human faculties like imagination, moral sense, religious instinct etc) not about the rationality of the universe.

But also, if you’re going to bandy about words like “magic”, then you really need also to do some homework on the rise of magic from its eclipse under Christianity in the middle ages, through its rediscovery in the Renaissance hermetic literature, and its integral role in the history of early modern science. It’s part of the now mainstream view of historians of science, together, of course, with the dependence of modern science on Christian creation doctrine, which has thoroughly overturned the “science-religion” war view of the nineteenth century. This might be helpful as an introduction.

Jon, I commented above only on the Lewis quotations you gave. We weren’t talking about how rationality arises (though this has a clear answer under evolutionary theory, contra Nagel). The claim under discussion was that science presupposes that the universe is rational, and that this is a merely metaphysical prejudice. That claim is false. The second quote you gave from Lewis seems to confirm that I read him correctly: “This would mean that the sole ground for believing [evolution] is not empirical but metaphysical”. That’s a crazy statement. Evolutionary theory makes many unexpected and surprising and very detailed predictions, as do QM and relativity, and that is why we think these theories capture, at least approximately, something about reality, so that tentative belief in them is justified.

Regarding the broader claim that rationality is not justifiable from outside a rational framework, why don’t the successes of its surprising predictions count as justification for its utility?

No Lou, sorry. You were discussing the claim that the universe is rational. I was discussing Lewis’s claim that in order to believe that the universe is rational, you have to believe in the power of human reason to assess it truly, which is not warranted by the Myth in question – that “reason is simply the unforeseen and unintended by-product of a mindless process at one stage of its endless and aimless becoming. The content of the Myth thus knocks from under me the only ground on which I could possibly believe the Myth to be true.”

Maybe you should read Lewis’s essay – I kind of assume that anyone commenting on points I draw from his arguments will read the arguments.

Re your last post, Alvin Plantinga makes a detailed argument in Where the Conflict Really Lies. Another one for the reading list, to add to Nagel and Lewis. And Henry.

Briefly, reason evolved, if it evolved in a Darwinian fashion, as a mere survival tool, not as a means to discern truth. Plantinga gives examples of how that might work – I’ve not time or space. Not all that works is true, and the fact that events correlate with thoughts and expectations about events is no guarantee that the explanations for them are true objectively.

For example, human reason determines laws of logic (which I happen to believe true), by which all scientific findings are assessed. But the truth of those laws themselves is validated by … oh yes, human reason itself. Accuser, Judge and Jury.

In fact science, because empirical, has to deal with the evolutionary limitations of human perceptions as well as human reason. And if, as sometimes happens, perception disagrees with reason, it has to prioritise reason (evolved, magically reliable) from perception (evolved, mysteriously unreliable).

And that’s the same human reason that, back in early modern times, led a genius like Leonardo da Vinci to consider that the making of a working model of a dragon was supporting evidence for their existence… and of course, more positively and a few centuries earlier, Thomas Aquinas to delineate five rational proofs for God (independent of perception).

Christians (eg most of the founders of science) take it on faith that the rational Creator has made nature orderly and rational, and also made his rational representative, mankind, able to perceive and reason about it correctly. Materialists have to believe that blind and mindless processes have delivered the same result.

“…Reason evolved, if it evolved in a Darwinian fashion, as a mere survival tool, not as a means to discern truth.”

That’s right. We have no guarantee that the products of our reason are true. And science never tries to make such a guarantee.

It doesn’t matter at all whether our theories are the product of rational thought or a random accident of typographical errors.

We judge the degree to which theories correspond to reality by an interesting process that looks not just at confirmations but at other qualities. The combination of compactness (“elegance”) and reach (or power) is nearly impossible to obtain unless a theory does capture something true about reality. And that is all scientists can expect; we don’t guarantee that it IS true.

Regarding your last point, rational thinking about at least the basic aspects of the world would seem to often have big advantages, in terms of survival value, over less rational reasoning. I don’t think the evolution of good thinking skills is mysterious. As to why the universe is rational, I think the materialist explanation is much better than the Christian one. Under the materialist view, whatever exists must be logically consistent, and this implies that at some level it should obey a mathematical description, with real laws that are logical consequences of the properties of the things that exist. Under your view of creation, you have to explain why the universe doesn’t show evidence of “mind” or “personality” above the laws that govern the material world.

Of course you as a Christian would deny what I am trying to explain, as you believe that “mind” or “personality” can make things happen that violate these laws.

Jon, I normally have to rely on, and respond to, your posts rather than the original articles, for lack of time. I apologize for that. In Lewis’ case, I had long ago lost respect for him as a good thinker, after his dopey “liar, lunatic or Lord” argument. He won’t be high on my “to-read” list.

I see in Wikipedia that even NT Wright thinks Lewis’ arguments don’t hold water.

Yet isn’t NT Wright (forgive me if I’ve confused him with someone else) the guy you attacked on BioLogos for the even dopier argument that the Resurrection must be a genuine historical event, because the followers of Jesus would never have written or spread such a tale unless it really happened?

If Wright, by your standards, can’t think straight, why should you think his arguments against Lewis would be based on straight thinking?

Hi Eddie, yes, NT Wrighyt has a lot in common with Lewis; he seems to be more of a propagandist than a critical thinker. That’s why I said “EVEN NT Wright….” I don’t trust his judgement, but I remember that most of the religious commenters on BioLogos do. That’s why I mentioned him–for you.

One doesn’t have to accept every single argument put forward by a thinker in order to recognize the value of a thinker.

I never liked, the liar, lunatic or Lord argument either, and indeed, as that was one of the first exposures I had to the thought of Lewis (when I was a teenager, and rabid Darwinist, as you are now), I classified him with really dumb American fundamentalists in my mind, and refused to read him. Later on, for various reasons, I ended up reading some of his better apologetic essays, and some of his literary works, and I came to see that there was a whole side of Lewis — the supremely cultivated European man of letters, with great insight into literature, a gift for making difficult philosophical and theological ideas clear, and a keen perception of the ruling ideas of our civilization — that I had previously known nothing about.

I haven’t read the particular essay that Jon is discussing, and so won’t comment on it. But Lewis at his best remains quite a perceptive thinker. There was a list of the 100 most important books of the 20th century put out years ago by some American organization. The list included seminal works such as Brave New World and 1984 and so on. Lewis’s The Abolition of Man was on that list. Even if one entirely rejects his religious conclusions, his philosophical and cultural analysis is at times very impressive.

That’s interesting, I might try some of his shorter essays…

Lou

I’d like to follow up my comments in the previous thread and your response as above that “magic” could be confirmed by science as a part of nature.

It’s good to observe the distinction between “material” and “physical” phenomena. Gravitational and magnetic fields are strictly speaking not “material” but they are physical. They are invisible and intangible and have a mysterious quality, but—and this is the key point—they are measurable, or if you prefer quantifiable, and therefore testable scientifically.

Generally speaking, science recognizes as real that which is measurable. If some kind of magic were quantifiable, capable of being described and verified through mathematics, science would encompass it as a physical phenomenon. It would no longer qualify as “magic,” any more than magnetism does. All that would remain would be to link it to other physical phenomena. One of the aspects of the scientific enterprise is to unite all measurable phenomena into one seamless mathematical structure. A step in that direction was the unifying of the electromagnetic and weak nuclear forces at high energy levels, as I understand it. Unifying GR and QM is a major goal for the future.

Science is therefore blind to that which cannot be quantified.

The superstitious or “magic-oriented” mindset acts upon impressions without resort to quantification. To the extent that someone begins to demand measurable results they are no longer in the thrall of magic-oriented thinking; they are in the thrall of a different, mathematics-oriented intuition. The two ways of thinking are incommensurable. You cannot disprove one by means of the other. You pays your money and you takes your choice.

Now, I don’t believe that all that is real is quantifiable and testable. Objective moral values are a counter-example. Nevertheless, quantification does disclose a great deal about one side of reality, the physical side.

Darek

Another aspect of this “mathematical v magical” thought polarisation is the phenomenon of non-logical thought patterns being one of the main drivers of new knowledge, including scientific knowledge.

Mathematics and rational arguments should actually be seen as confirmatory tools, rather than the usual source of insight.

We covered that here in the writings of Michael Polanyi a little while ago. His CV shows he was no slouch as either a scientist or a thinker.

Yes, there’s no disagreement about that. Big new theories are creative acts like making a great piece of art– they are not merely deduced from the data.

Darek, instead of saying “Generally speaking, science recognizes as real that which is measurable”, I think it is more correct to say that science simply demands good public evidence for what is real. I deliberately didn’t use words like “supernatural”, to avoid the semantic issue about whether science could ever recognize something as supernatural.

Let me explain what I mean by “magic”, since Jon criticised my use of the term, and then I think you’ll see that science could indeed recognize this if it were real. By “magic” I meant that mind can trump natural laws. For example, a ritual or words or symbols could have direct causal influence on the physical universe because of their meaning rather than through physical causal chains that are blind to what the rituals, words, etc signify. Saying the word “abracadabra” instead of “Hot cross buns” should not make a bunny materialize in a hat, especially if the hat were far from the speaker and isolated from the sound waves he produced. If it did, that would count as magic. The Bible is full of magical events, and the Israelites clearly thought this was a magical world. The Red Sea parts on cue, Lot’s wife turns to salt, etc. (Incidentally, the Bible grants magical powers not just to Yahweh and his followers but also to other gods and their followers–eg the Egyptian priest was able to invoke his gods to turn his staff into a snake in front of Moses….)

Now, if this kind of magic were common enough, and especially if it were repeatable, scientists would accept its existence. If it were common and regular, it might even be incorporated into laws of magic. But these would be very different from any current laws, in that they are sensitive to the meaning of the cause rather than its physical structure. We would be living in a magical world. There is nothing intrinsic to science that prevents it from discovering and accepting this, if it were true.

Lou

Evidence that is not measurable is not “good evidence” in the scientific sense. Repeatability entails measurability, which in turn entails susceptibility to mathematical analysis.

The events you cite from the Scriptures are portrayed as exceptional, not as representative of everyday reality. Ancient priests were presumably skilled at creating illusions to give themselves credibility, so its difficult to make a case for ancient gods such as Chemosh or Baal as active agents in the Bible.

However, you bring up a relevant point concerning the meanings of symbols as opposed to their physical properties. The meanings are abstracta. In the workings of a computer, it is the physical properties of symbols that do the causal work. What about our mental processes? These are dependent upon chemical processes in the brain. So how can the meanings of symbols, abstracted from their physical properties, play a causal role in our thought processes?

C. S. Lewis made the case for other-than-natural effects–miracles of a type, if you will–because our thought processes are responsive to pure abstracta and not just physical properties.

Lou, you do raise the challenging [but I still think unsubstantiatable] point that science can rise by pulling its own bootstraps as an independent entity. If I understand you correctly it could be summarized thus: “But we don’t need to depend on any extra-scientific philosophy, religious sanction, or any intellectual hocus pocus to substantiate the process of science. It speaks for itself when airplanes fly, computers work, etc.”

I think this still runs afoul of being a trivial tautology that could be summarized this way: Science has unrivaled success because it unswervingly holds to the conviction that we can depend on reality to continue doing what science has discovered … reality does.

That our minds can apparently discover and appreciate that … and do so according to mathematical patterns that we can also apprehend is also amazing. But the trustworthiness of the human mind [in its collective sense] is not something that science can rule on. That is what Lewis points out that I’m not sure you fully appreciate. You insist … but look at all this science that leads to all these things that work so well! To which comes the fatal reply “… so says the mind that was shaped by evolution merely to survive with reproductive advantage.” There is no guarantee that a culture believing many false things (say, for example, being convinced that other tribes are always out to kill them, when their fear is actually inflated to paranoia) will not derive enhanced survival skills from their false belief as an advantage over another tribe that may have truer beliefs.

As Lewis would say, you have some branches (science) rebelling against their own supporting trunk (the human mind) by reducing it to a mere artifact shaped by random processes from nature alone. It does no good to desperately point at any alleged universalities, repeatabilities, workabilities, etc. since the evaluation, judgment, and interpretation for all these things resides in … your own spuriously-conditioned mind. Such is the problem for the materialist.

I don’t see that, Merv. First, I don’t think there’s a tautology, because our theories predict things beyond the observations that initially inspired it.

Second, sure, our minds aren’t guaranteed to produce truth. But that’s why we don’t stop there, we do public experiments. We (usually) aren’t fooling ourselves about the agreement between theory and reality, and indeed that is what science is all about, trying to keep us from fooling ourselves.

It seems to me science and religion split dramatically here when it comes to reliance on what our minds tell us; religious people generally accept personal experiences of the divine at face value (forgetting that evolution might not have perfected our perceptual abilities) while scientists (who realize the fallibility of perception and introspection) look to outside arbiters. So it seems to me the kind of objection Lewis brings against science is actually much more powerful as an objection against the religious person’s reliance on personal revelation.

Lou, you’re the second atheist friend I have that has explicitly written Lewis off (in his case also because of an argument that he thought very weak.) Could it be that atheists are afraid to delve to deeply into all the depths of his prolific writings? I mean … good grief … I don’t agree with everything he writes either; I’m an Anabaptist, after all! And I think Lewis’ moral argument as an evidence for the existence for God has been refuted (by a Catholic, I believe). But despite his failure to publish perfection, he still has much insight that remains pertinent and (I think) true.

But regarding a lack of time to read everything, I sympathize. Picking and choosing is another reality thrust upon us.

Merv, yes, there are so many intriguing things I really want to read, and so little time. I have read bits and pieces by Lewis, and I never saw anything that was even intriguing. That’s in contrast to some other writers I disagree with, who at least make arguments that are thought-provoking. I just don’t see that in Lewis, who seems to be more of a propagandist than a careful thinker.

Of course, among “propagandists rather than careful thinkers,” please make sure you include Larry Moran, Jerry Coyne, P. Z. Myers, Richard Dawkins, Jeffrey Shallit, Nick Matzke, Eugenie Scott, Robert Pennock, Barbara Forrest, the vast majority of posters at The Panda’s Thumb, etc. None of these people can think their way out of a wet paper bag, in any matter outside their very narrow scientific specialties — and in even those specialties, a number of them are mediocrities at best.

Lewis, on the other hand, was a world-class scholar in Medieval and Renaissance Literature, and held the chair at Cambridge in that field; prior to that he was an accomplished student of Classical language and literature, and one of the movers and shakers behind the Oxford Socratic Club, a recreational philosophical organization at Oxford where some of the top minds sparred; and of course as an Inkling he was a contributor to an original literary movement in Britain. He certainly had a much richer, broader, more reflective, and more cultivated mind than any of the people I’ve named above — indeed, than all of them put together.

Of course, that might not be evident if all that you have read is snippets of his apologetic works. When you look at his whole academic and literary output (of which his apologetics work was only a part), he is a very impressive figure in English letters.

Lou wrote: “religious people generally accept personal experiences of the divine at face value (forgetting that evolution might not have perfected our perceptual abilities) while scientists (who realize the fallibility of perception and introspection) look to outside arbiters.”

Not outside of science they don’t. Religious people (who are generally less in denial about their own metaphysical presuppositions) have the advantage over you in that they can choose to take scientific *and* other experiential evidence into account from wider domains and cultures. While you see this as a faulty tainting of good evidence (scientific) with unreliable evidence (everything else), that metaphysical faith commitment of yours is a product of … your own conditioned mind (in the materialist’s view) fed by all sorts of things from that latter category that you want to pretend you’ve left behind.

I just ask for good evidence. I don’t restrict the domain from which it comes.

We know people delude themselves all the time about all kinds of things. Lewis was at least right about that. Our brains evolved under selective pressure not to give us truth but to increase our likelihood of survival. So it should be obvious that we have to check and double-check our experiences in order to get closer to the truth. How can you argue that we should take personal experiences of the divine at face value, given what we know about how easily we fool ourselves?

“I just ask for good evidence. I don’t restrict the domain from which it comes.”

“How can you argue that we should take personal experiences of the divine at face value, given what we know about how easily we fool ourselves?”

Read both of these sentences above, one after the other. It would be difficult to lay out your own contradiction any more clearly, but the key is in your qualifier for the word “evidence” with the word “good”.

Obviously any testimony over personal experience *which can’t be verified in a repeatable or at least universally observable sense* (i.e. ‘scientific’) is (at best) put on probation awaiting verification from your only real acceptable category of evidence. But more typically it is rejected outright, given that you don’t have time to investigate or read everything that you have already ruled out as nonsense –a genuinely limiting factor that we all share.

Let me hasten to add, that I *don’t* accept all accounts of experiences of the Divine “at face value”; nor do most Christian thinkers that I have read or know.

I refrained from challenging this assertion of yours because you did qualify it with the word “generally” in a previous post: “…religious people generally accept personal experiences of the divine at face value…”, and that qualifier is vague enough to allow that the statement *may* be more or less true.

But religious and theological claims have their own accepted methods for checking or filtering claims which (for thinkers) will include scientific as well as other legitimate theological resources. So I suggest that Christian thinkers/writers/historical movers & shakers aren’t generally as credulous as you make them out to be.

Merv, that process seems circular to me. I imagine the procedure is to compare the revelation for consistency with whatever religious beliefs you already hold, but you don’t have an external check on the validity of those beliefs.

I don’t see much skepticism on display among people who claim to have received personal signs or revelations. Many such claims seem jaw-droppingly naive. An example is Francis Collins’ three frozen waterfalls.

“Read both of these sentences above, one after the other. It would be difficult to lay out your own contradiction any more clearly, but the key is in your qualifier for the word “evidence” with the word “good””

Merv, there’s no contradiction. I don’t discount personal revelation, I just require that it hold up to ordinary standards of evidence. It doesn’t get a free pass. For example, if revelation ever contained improbably new information that could be verified, this would count in its favor.

We have to demand some kind of evidential standard, or else we’re faced with multiple conflicting claims about revelation, ranging from claims about space alien saviors to a wide gamut of crazy cults and established religions.

Yes, I tend to ignore revelations, especially when they are based on a backstory which doesn’t make sense or is contradicted by other evidence.

” I just require that it hold up to ordinary standards of evidence. It doesn’t get a free pass.”

“ordinary” = “scientific”

Regarding the free pass, I guess your faith in the scientific processes as the best way to all valid knowledge is the only thing that does get a free pass, then, since it can’t referee its own competition, and nobody else qualifies on your estimate as a more reliable authority to fill the job. I know … science bootstraps itself up to authority on its own merits because within its own context it’s the most reliable thing we’ve got. I.e. it is good at what it does. So all other academic disciplines are just supposed to kneel in petitionary supplication at the altar…

I guess we’ll leave this where we usually do … disagreeing, but thanks for the civility.

Thanks also for your sincere responses.

I am open to other, non-scientific ways to find valid knowledge. However, I don’t see that religion has given us anything that can be called knowledge. Even among people who do think religion gives valid knowledge, there is not even any approximate consensus on what that knowledge might be. Religions continue to splinter freely over time, with each branch generally thinking that it alone has the right answer to some religious question, and there is no generally agreed-upon criterion for deciding who is right (if there were such a criterion, we should see more consensus).

I do not want to become involved in a discussion with Lou on this thread, but instead would offer a comment on using the term “magic”, in opposition to the term “scientific”. If such discussions occurred say in Athens during ~500 BC, everyone would have understood and be familiar with “magic” (whatever their beliefs), while few would distinguish terms such as “scientific” from “philosophical”.

We may also reflect on natives given mirrors and other trinkets by white settlers, to take advantage of the easy belief by natives of the magical.

A (secret) observer would report the facts of the events and artefacts, but the culture and background of the white would be to deceive, while for the natives, their culture and experiences would provide a context for meaning and understanding. The facts are neither scientific nor magical.

My objection is to the misuse of terms such as magic in discussions of the scientific, because nowadays the meaning is automatically given, which is that one term is the opposite of the other. An additional objection to the use of such terms is more difficult to understand, but such discussions may often be understood as making science a thing, which determines meaning and understanding to human beings. This is best described as the flying spaghetti monster (FSM) running around filling minds with meaning stemming from itself (this ironically would be the epitome of the magical).

The enchanted and emotionally attractive in human experience is most often understood through aesthetics and the arts. Ethics provides both the good (in as much as we may understand this) and also may display the beauty and value in the good. The religious attribute, within such discussions, is one dealing with faith and reason – in this way, we may be thankful the red sea does not part at irregular intervals (by magic or due to the FSM, and be filled with awe when we read of a singular event when it did part for Israel.

Guys, an essay on the theme of the scientific epistemology that you’ve been discussing here.

The scientific equivalent of “The Striptease of Humanism.”

PS: follow his links (or mine) to:

http://www.cornwallalliance.org/blog/item/wanted-for-premeditated-murder-how-post-normal-science-stabbed-real-science-in-the-back-on-the-way-to-the-illusion-of-scientific-consensus-on-global-warming/

and to:

http://buythetruth.wordpress.com/2009/10/31/climate-change-and-the-death-of-science/

Forget the issue of global warming as such, but concentrate on postmodern science, against which I think Lou and most of us would be co-belligerents. Beisner’s thesis is that the reason for postmodern science is that real science cannot stand forever without the underpinnings of its roots in creation doctrine, as we’ve been discussing. If one disagrees with that, the job spec is to find a more valid interpretation, since it looks as if the ideology of science is seriously under threat in the coming generation.

Jon,

I can agree from personal experience(s) with these sentiments regarding postmodern science – although in the corporate world few of them are bothered by, or even understand such labels. On climate change, I predicted the politicisation and resulting polarisation at a university seminar I gave about 10 years ago – I had a discussion recently with a friend who is sincere and active on the need to act on climate and Greenhouse gases, but when I pointed out the difficulties that politicisation of the science and the inadequacy in models, he was taken aback. This illustrates the powerful impact science can make on intelligent citizens when it is manipulated by politicians (which includes scientist who have left science and are now politician’s servants).

More sobering and surprising has been my experiences (many years ago) where corporate entities became so intent on self promotion, that the corporations bottom line was trashed, but the (pseudo) scientists and engineers were able to negate the profit motive, something sacred to corporations – their catch cry was, “this is how we do science”, and we have “found our sugar daddies!”

Although I could negate their impact on the area and science I controlled, other areas were no as fortunate, and hundreds of millions of dollars were wasted on creating technologies that were MORE polluting then the present ones. This example illustrates the power such people may exercise by offering science to their political masters.

I shudder to think what such people can do to the faith-science enterprise.

Another consideration, GD. “Post-normal science” is carried out by the same kind of bright university people as is real science, with the same “evolved” faculty of reason, the same natural phenomena and even many of the same methodologies.

The only difference is the underlying philosophy and ethic, which shows that, as we have been suggesting, you can’t assume that reason alone will get you to consistent answers.

That’s why, I suppose, the Gnus are inclined to rubbish the intelligence of their opponents: they believe their reason is just too undeveloped to embrace materialist truth, so they are all hill-billy creationists, IDiots, senile (Flew), shoddy (Nagel) etc. Whereas they ought to be bright, like them. But that ploy gets harder when science itself starts taking on a new flavour – after awhile you end up the only ones who managed to evolve reason.

The difference in the science-faith enterprise is that reason is not absolutized in Christianity, and neither is any other human attribute. Revelation remains as an authority above them all, though as you suggest there have always been those in thrall to the spirit of the age. Postmodernism infected theology before it got many inroads into science, sad to say – but as Richard Baxter wisely said 3 1/2 centuries ago, “Scripture does not change.”

On the matter of reason and intelligence of such bright atheists Jon, I cannot get past (I think it was Rosenberg) the ‘bare faced’ statement that natural selection has created an illusion of reason and intellect (and accompanying attributes such as free will) – how can anyone function intellectually with such a belief? I guess NS will provide, provided an atheist believes!!?

Revelation however as a doctrine is a two edged sword – and that is because it all rests on the doctrine of Grace; however we are shown that reason, virtue, truth, etc., are all intricately and organically intertwined with the Faith. This why I take the view that God can handle all of these matters – and if we have faith, our own personhood and the society we are part of will inevitably benefit from the teachings of the faith as a practical proposition. Ironically, I include atheists of good will within this view.

Those are disgustingly-written links by people who are more agenda-driven than the people they criticize, but as you suggest, I’ll let that go. I don’t think the creation doctrine has anything to do with the problems in science today. I think the issues are (1) primarily the great expense of much modern science and the concomitant dependence on centralized funding, which is almost always either overtly political (government funding) or self-serving (eg climate-change denialist foundations like the Heartland Institute, funded by oil billionaires), and (2) the fact that science has become a career for many practitioners, so that the goal shifts from pursuing truth to making a living.

I don’t know what the solution is, except to expose malpractice. I think the internet is a great innovation in this regard, especially post-publication open peer review, recently instituted by some of the biggest funding agencies in the sciences.

I do think that scientists who are sure they have found a strong effect in some area that impacts the public well-being should become public figures and should voice their concerns widely. They have a responsibility to to do. Rachel Carson, a pioneer American environmentalist who wrote the influential book Silent Spring (about the environmental impact of pesticides), comes to mind as someone who did the right thing and had enormous political impact.

I’m going to chime in with Lou on this … Neither side of the climate change problem can claim to be free of heavy corporate motivation. So for deniers to insist that only the promoters are tainted with profit motivation seems silly. For every corporation that stands to gain from climate change promotion are others who stand to gain by promoting business-as-usual. But that leads to the real point Jon is addressing…

I have a problem with all this. It presumes that science has *ever* been free of values. And in fact (with Lou) I’m not convinced it always should be. Think of Patterson (highlighted in one of the Cosmos series) fighting the big oil companies over the issue of lead poisoning … and fortunately for all of us, Patterson finally prevailed over his Goliath.

There has always been a dance between collecting/organizing information disinterestedly and then acting on it. If you take away the latter part of that balance then you have lost perhaps the primary reason for being interested in the former (why know things in the first place if acting on that knowledge is verboten?)

There is such a thing as overwhelming consensus. And it may be appropriate for a scientist to defend that consensus (thus invoking the indignant wrath of her opponents who accuse her then of activism) by using the data and reasoning at hand. In the articles they made much of scientists studying “climate change” (inherent presumption that ‘change’ is a given) rather than studying *if* climate change is occurring. With all due respect to you, GD, or others who may have their own valid reasons for nurturing a healthy skepticism. But over more the wider issue of whether scientists should ever presume some things, surely we all agree this is often appropriate? If somebody in my physics class takes affront of our presumption that the earth moves, I may well take that as a great opportunity to rehearse how science has historically worked on just such an issue, but I won’t halt my course for a few weeks to seriously re-open and investigate that issue as if our answers to it were prematurely concluded and need to be called back into question (not that such an exercise couldn’t be of immense value in a physics class … but it would come too much at the expense of other subsequent material we would never reach.)

I object to the post-modern denial of objective truth just as much as everybody else here. But I think we are naive to think that science ever existed in some value-free sense. Geniuses from Boyle to Einstein may have had pure knowledge as a premium (perhaps even highest) motivator for their work, but not far behind would be an excitement for how such things might prove useful.

I do agree the danger to science today is real (and even probably fatal) when science purports to be some sort of independent system from all faith values.

So to the extent that this core concern was expressed in these articles, I do think they are right to point it out –too bad that they chose an issue (climate-change) over which they are in every bit as much in the corporate muck as their opponents to try to illustrate the problem.

Thanks for that Merv.

Climate change is a little bit less controversial here – in fact, it’s strange that if there’s a news item on it in, say, the Independent online, there are usually 500 comments from Americans of various persuasions slugging it out. More significantly it’s really not a shibboleth for Christians at all, unlike the US, where it seems to be part of the conservative-republican-creationst/liberal-democrat-evolutionist package. Most believers here believe it’s real and as important as other global issues. So forgive me for drawing attention to it.

Your points about the inevitability, and Lou’s about the desirability, of ethical/political commitment are well made. But as you say, it speaks against the very possibility of absolute objectivity in science, and sows the seeds for its corruption as in this “post-normal science” (which I hadn’t heard of before today, but which makes sense of a number of things).

There was a time when the prevailing zeitgeist was that science must make hard choices for humanity – like racial eugenics. It was, of course, linked to the myth of progress and the politics of fascism.

Lysenko subordinated science to the “greater” truth of Marxism.

Mary Schweitzer’s boss, apparently, wasn’t too happy for her to publish her work on soft tissue fossilisation in T Rex – encouraging the Creationists is sometimes seen as a greater evil than releasing anomalous data.

I was going to round it off with the Church’s attitude to Galileo, but that’s actually a more complex example, as Ted Davis covered at length on BL.

Merv and Jon:

I agree that climate change proponents and opponents (I don’t use the word “deniers” because it is pejorative and rhetorical) may both be accused of vested interests. Opponents can be accused (usually the accusation is false, but leave that aside) of being in the pocket of corporations who want to pump out greenhouse gases; and proponents can be accused (not always fairly, I would guess) of offering exaggerated and irresponsibly alarmist conclusions, on the grounds that alarmist conclusions are far more likely to earn them fame and get them big research grants from governments than modest, qualified conclusions (e.g., there may be a human contribution to the warming, but we aren’t sure how much, and even if we could be sure how much, we aren’t certain what the best policy response would be).

The argument should always be about the evidence, not about people’s alleged motivations.

Aside to Jon: there is increasing doubt both about the basic facts of global warming and about the degree to which the warming is anthropogenic. I recently read an article on polar bears in which it was pointed out that, despite touching pictures showing polar bears stranded on ice floes, no rigorous count of polar bears in the Arctic had recently been done, so that the conclusion that they are all dying off due to global warming was anecdotal and scientifically irresponsible. And last year the Arctic sea ice, during one season, reached a near-peak for something like the past 30 years, which at least at first blush contradicts the hypothesis. The increase of ice in parts of Antarctica is well-known, as is the embarrassing retraction the AGM people had to make about the melting of all the Himalaya glaciers. And of course, where I live, and in a quite extensive region of Northeastern North America surrounding, the winters have been noticeably colder, and the summers noticeably cooler, than the original global scare model’s predictions, for something like 5 of the last 7 years.

All such observations, of course, are simply brushed aside by the theorists, who seem to care nothing about evidence and only about the defending their models. In the meantime, it is becoming more common for scientists originally onside to question the global warming models — much more common than for biologists to question evolution, for example.

That the world is a degree or two warmer than it was 100 years ago, I do not question. But three things are certainly debatable: (a) whether the patterns and observations of the past 10-15 years (including an inexplicable flatline that was supposed to turn upwards again in 2011, but didn’t) are consistent with the catastrophic predictions of global warming writings; (b) even if the warming pattern resumes and follows the models exactly, how much of the warming is due to human production of greenhouse gases, as opposed to natural causes typical of long-term weather cycles (we know the Ice Ages weren’t caused by human production of greenhouse gases); (c) whether Western countries are under the moral obligation (insisted upon by pampered, well-off leftists like Al Gore in the USA and David Suzuki in Canada, shielded from the consequences of unemployment no matter how many North American factories close) to ruin their own economies by adopting stricter emission standards when greater polluters such as China and India are not.

I actually regard the “consensus” about AGW as something very much like the “consensus” in favor of neo-Darwinism. In both cases, we have seen bullying and ridicule and accusations regarding motives substituted for actual argument; in both cases, data has knowingly been falsified or suppressed or massaged so that the public will not know what it originally indicated (cf. the Haeckel drawings in the Darwinian case, and the famous leaked emails in the AGW case).

I have no dog in the fight regarding AGW in itself, but in terms of the politics of the movement, the leaders of AGW have shamelessly used culture-war tactics to bully and browbeat everyone into submission. I distrust any scientist who behaves in that way. An honest scientist would state his results without alarmism, with all due qualifications and uncertainties, and with full disclosure concerning all massagings of data done to bring the model into line with reality. And an honest scientist would not be plotting in emails with other scientists how to disqualify scientific journals which do not toe the party line.

The public is starting to realize that scientists are mortals, with feet of clay, prone to dishonesty and vanity and greed and careerism as much as anyone else. This is a complete changeover from my youth. When I grew up, scientists were treated almost like gods. The name “Einstein” conjured up immediate reverence. Men in white coats were always saving the world from monsters and aliens in the movies, and in real life were curing diseases, inventing laser beams and spaceships, etc. The myth of the scientist as the person who cares only about truth and has no dogmas was widely believed. I wanted to be a scientist, growing up. But after reading P. Z. Myers, Jerry Coyne, Eugenie Scott, Rob Pennock, and the global warming conspirators whose emails were leaked, I find my estimation of the integrity of scientists has gone way, way down. (Of course, knowing a good number of scientists personally has helped, too; when confronted by the person rather than the myth, one is less impressed.)

I retain my belief that science, properly conducted, is a great blessing to the human race and a noble calling; but I find the new style of self-promotion of scientists — bullying, blogging, courting audiences of vulgar groupies on the internet, trying to prevent scientists with unorthodox views from ever getting tenure, competing viciously for grants and prestige, etc. — to be extremely disappointing. And when I think of the AGW lobby, all of this comes to mind, because of the tactics it has employed.

Eddie

The fact that there is a controversy about the science of global warming is evidence in itself that once science compromises its philosophical and ethical basis and becomes something else, its authority vanishes.

Broadly, the Christian foundations meant “There is truth out there, because a true God is behind it.” Postmodernism, in effect, says “There is no truth out there – we have to nake it ourselves.”

To the extent that tells us we were always looking at “God’s truth” through human spectacles, that’s maybe of some value. But when the spectacles become all one believes there is to see, it’s tragic.

The debate on climate change and the politicisation illustrates one important point that imo is often ignored in these exchanges/discussions. This point is the character of the scientists, and the public response (esp in the media) to look for the spectacular and not what is sound.

Good science is done by good people – those who display the character formalised by ethical principles. The Gospel has shown us in many ways, that God is interested in good people – thus He does not seem to bother Himself with rhetoric, but with the actions of people.

Once the public tries (with great difficulty) to equate good science with good people, and bad science with bad people, controversies on GHG will cease.

But wait; I just reminded myself that once good people are differentiated from bad people, almost all of our difficulties on this planet would be addressed and eventually solved, What am I thinking when I say such things? And what has this to do with Faith?

(I guess I jest!)

Faith is not a source of knowledge, GD. If you want an objective measure of which scientists are ethically good, and which are bad, then science must provide the answer… no, hold on…

One other quick comment on the essays—I think it is an exaggeration to say that science depended on a Christian worldview. Much scientific thinking really started (as far as we can tell–earlier cultures may have made more advances than we know) with the polytheistic (and sometimes atheist) ancient Greeks. And frankly, I don’t think it was because of their brand of polytheism that it started there. It was because of inquisitive minds which their culture somehow nurtured.

If Christianity was so important to science, why did it take 1500 years to have this effect? In those one and a half millennia, “Scripture does not change”, but the secular cultural milieu did changed. Ted Davis on BioLogos makes the case for the importance of Christianity for science, especially the doctrine of voluntarism, but his same argument implies that pre-voluntarism Christianity held science back. I don’t see that Christianity was as influential as secular changes in society at that time. Sure, many great scientists of the time were Christians (like most people of the time) and felt that they were uncovering aspects of the divine. But that possibility was always there in the 1500 years prior to their time. It can’t be the most important explanation for the scientific advances of the time.

Lou

Of course science didn’t begin 500 years ago – that’s another version of the modern conceit that we know best. Hannam shows how science and mathematics were both established in mediaeval Europe, largely through the universities. He also gives indications as to the factors why it didn’t happen earlier – the barbarian defeat of Rome and the Islamic overrunning of the East being significant factors.

I recounted how the intellectual tradition and a new empirical, creation-based method of enquiry was maintained in the monasteries well back into the first millennium.

Jaki was amongst the first to show why other cultures, including the Greeks, never really got science going despite their philosophical and mathematical achievements (Archimedes being almost alone in this).

The reason Ted Davis emphasises the central role of Christianity is because that’s what mainstream history of science has been saying for several decades. It isn’t even controversial, which is why the sources I quote here are trying to explain the why rather than the what. You need to be aware that Henry’s book is the standard text for the Open University History of Science degree here. And Hannam’s book was shortlisted for a Royal Society science book prize in 2010.

“The reason Ted Davis emphasises the central role of Christianity is because that’s what mainstream history of science has been saying for several decades. It isn’t even controversial”

Jon, nearly everything you write on this blog about evolution is contrary to the mainstream views of my own field. My positions on evolution aren’t even controversial in evolutionary biology. I am sure you will agree that this should not prevent either of us from criticizing some aspects of mainstream views.

I am not an expert on the history of science, and I don’t regard my position on this as settled. I could be wrong.

Wow, I’ve just read the foreward to Jaki’s book. What ethnocentric snobbery! The first two paragraphs are full of Judeo-Christian prejudice. This is what makes me suspicious of much of the literature on this subject. I know the foreward is not Jaki’s writing, and I’ll look a little deeper, but it’s off to a bad start.

Even a snob can be right.

Almost every sentence of those first two paragraphs in the Foreward look wrong to me.

“Foreword…”

Jaki often writes with great haughtiness and arrogance. This is partly personal with him — he could be a condescending, pompous man in real life, very proud of his accomplishments and very dismissive of intellectual opposition. He also has a very strong Catholic prejudice in the way he writes history of science. He writes with unnecessary contempt for both Protestant and non-Christian traditions. I don’t recommend most of his work, except for Science and Creation, which, if one can endure the cultural condescension, has the virtue of offering a clear historical thesis which an undergrad can grasp.

There is better scholarship, and scholarship written without the condescension and the Catholic partisanship, by Protestant, Jewish, and secular scholars, on the relationship of Christian theology to the rise of modern natural science. Maggie Osler, a secularist who used to be at the University of Calgary (and may still be), comes to mind. A Catholic who is better than Jaki for detached analysis is Francis Oakley. Hooykaas, Michael Foster and others also make the case without the “attitude” that comes across in Jaki. Ted Davis himself is another very balanced, moderate Protestant scholar in the area.

As Hanan says below, even a snob can be right. So one shouldn’t throw out a conclusion merely because some of those who advocate it are unpleasant. It’s better to find the writings of a non-snob who holds the same position, in order to be able to analyze the position unaffected by the personal irritants.

It has been pointed out by Ted Davis that in many academic areas, most of the best writing is still not available on the internet. This is definitely the case in the area we are talking about.

Hannam’s book looks much better.

As an aside, I have to point out that the Judeo-Christian universe is NOT particularly rational or lawlike. It’s is a magical world, full of demons, inexplicable and even whimsical divine interventions, etc. Everything in the universe, every process and every being, even the motion of the sun and stars, is subject to the vagaries of mood of this god.

What do you mean by “the Judeo-Christian universe”? In someone like Dante, the universe is highly structured and orderly. This is also the case for many other Christian thinkers, including Aquinas, Kepler, etc. C. S. Lewis’s historical study, The Discarded Image, is useful in showing the tendency of Christian thinkers to imagine an orderly and rational cosmos.

Eddie, I’m just looking at the Bible, trying to keep later societal developments separate. The Bible is full of the things I mentioned. They have been emphasized or de-emphasized at different times in different societies.

Good questions, Lou. I think one Christian rebuttal to that is that no culture grows up and develops in an instant (such as within one person’s lifetime). Christianity didn’t spring, fully developed, into existence with Christ. It started (though one could even point to thousands of years of development leading even to Christ) and then proceeded with fits, starts, and lapses (collapses of empires and resulting chaos tends to set any organized progress back a bit … especially were it not for the church doing what it could to preserve knowledge through it all) … proceeded in some good directions and many bad ones through human corruption and quests for power.

And then, even despite wars and plagues that were still rocking Europe the explosion of modern scientific thought began.

I think it significant that the Greeks never really pursued their (often brilliant) philosophies with the same rigor of empirical study that the later western Europeans did. And Chinese also, had many brilliant inventions far in advance of when the west ever saw them (gun powder, compasses, rockets …) but somehow never pursued them with the same rigor of curiosity that lead to further discovery or questions about the cosmos. The Chinese still thought the world was flat long after the Greeks and later Europeans knew it to be round.

Granted, there are many reasons we could highlight to speculate why western Europe at that time was such a productive stew pot. Jared Diamond compares all the squabbling and competing monarchies –all afraid that their neighbors might capitalize on new knowledge before they themselves can — he compares that with the political monolith that was China (no fears from bordering rivals) and make a case for why Europe progressed to rapidly in technology … and its subsequent byproduct, knowledge.

But still, it does make one think, doesn’t it? At the very least Christendom certainly didn’t prevent knowledge, and the stronger case is made, in fact, for the contrary.

I should correct myself (with more than a nod to Hannan’s “God’s Philosophers”) when I said that “And then, even despite wars and plagues that were still rocking Europe the explosion of modern scientific thought began.”

That should be amended to “… the explosion of modern scientific thought continued.”

At most we might note that it accelerated, but also included some serious backsliding and deliberate forgetting of significant developments (including critiques of Aristotle) that had gone before. The significant contributions of the Islamic and Hindi world probably can’t be overstated, which doesn’t really help your thesis much, Lou.

Merv, thanks for the support above about the propriety of the activist scientist. Another good example is the group of physicists who went out of their way to make sure that the public knew the dangers of atomic war.

“The significant contributions of the Islamic and Hindi world probably can’t be overstated, which doesn’t really help your thesis much, Lou.”

Maybe I’ve misunderstood you, but it seems to that on the contrary, they prove my point. There is nothing about christendom per se that was essential for science to develop. Sometimes science flourished under Islam, sometimes it flourished in the Hindi world, and sometimes it flourished under Christendom. Sometimes it also suffered under each of those belief systems. The actual belief system doesn’t seem to be the driver.

To the claim that the Greeks were little concerned with empirical discoveries, I recommend your observation that it was the Greeks who figured out the world was round. And they incidentally also figured out other important empirical relations, like Archimedes’ famous relations regarding displacement and mass as Jon mentioned.

Many cultures made a start in scientific progress. However, no previous culture approached the Western Christian culture in that respect. The Greeks certainly progressed in mathematics and in some areas of physics. Their discoveries were essential to the later scientific revolution. Yet the Greek contribution was not sufficient. They had some concern with empirical discovery, but the concern was not consistent; they were predominantly focused on the mathematical and rational aspects of nature. It seems that the Biblical idea of voluntarism (God’s will contains an element impervious to human reason, which means that science cannot proceed purely deductively, but must investigate nature through experiment) was central in the rise of an empirical approach to the science of nature. This insight is now widely granted by historians of science, including non-religious historians such as Maggie Osler.

The historical argument is not “modern science is true, therefore Christianity must be true.” Rather, the argument is, “No one can say Christianity was unfavorable to science, because it provided the core, non-Greek understanding of nature which science required: the idea that nature is such that no amount of reasoning from first principles, no matter how acute, is enough to understand nature, without being combined with empirical investigation.” It’s possible that in another universe, something other than Christianity could have provided this basic insight, but in the world we know, Christianity was the religious background that delivered the goods.

The most likely alternate religious source was Islam. The Muslims revered Greek knowledge, and also had the necessary component of a voluntaristic notion of God. Perhaps, had the Greek-lovers rather than the occasionalists won out in Islamic theology, Islam would have played the historical role that Christian Europe was later to play. But Islamic theology came to overplay the inscrutable will of God and underplay Greek ideas of the rationality of nature, and in the end, science withered in the Muslim world.

We see the careful balance between Greek mathematical, a priori reasoning and empirical reasoning in early modern astronomy and physics, as Brahe, Kepler, Galileo, and Newton juggle empirical data and mathematical models in order to work out the structure and laws of the solar system. The Muslims erred too far on one side, and the Greeks too far on the other, to have produced this balanced synthesis. The God of will and the God of reason had to correct and complement one another.

That’s the epistemological case. The case regarding motivation, however, tips even more strongly in favor of Christianity. The desire to know God through understanding his creation is well-attested in early modern scientific writing; further, as historian Lynn White has shown, the motivation of charity (the relief of the human estate through the knowledge of and control of nature) long predates Francis Bacon, and can be found in medieval writings.

None of this proves that Adam fell, that Christ redeemed us, etc. What it shows is that Christian metaphysical and moral assumptions played a major role in the birth of modern science. Not the only role — causation in history is multifaceted, and religion is not the only factor — but a major role.

I would never argue: “Christianity gave us modern science, and modern science is great, so Christianity must be true.” But I do reject the “Christianity opposed science” narrative, which is 99% untrue for most of Western history, and even today, in the USA, is only true in a limited sense, i.e., certain narrow Protestants oppose a very small subset of the total of all scientific teachings (i.e., some teachings relating to origins).

I was probably hasty to include lump the [Hindu] science in with the Islamic contributions … the latter made so many contributions to our maths, while the Hindus led in using place value, though not much in their science.

The Hindi religion includes concepts of cyclical infinities along with a multitude of whimsical gods whereas Islam is monotheistic. I was just thinking of your thesis as being that religions generally are inimical to progress … and probably many are. But not so much the monotheist ones –especially Christianity, given when/where modern science seems to have flourished.

You wrote: “Everything in the universe, every process and every being, even the motion of the sun and stars, is subject to the vagaries of mood of this god.” [presuming you meant ‘Christian God’, there].

… which seems to be an extreme reflection of faithfulness and biblically-observed regularity much to the excitement of all the early great Christian scientists who were busy trying to think God’s thoughts after Him.

The Greeks certainly did have so many bursts of brilliance –so much of it philosophical and mathematical. As a trigonometry teacher I really admire the genius of Eratosthenes for so closely approximating the actual circumference of the globe by measuring two simultaneous shadow angles down separated deep wells. (How might it have changed history if Columbus nearly a couple thousand years later had heeded the earlier Greek wisdom and been possibly deterred from his voyage!)

But these flashes of brilliance failed to catch … failed to have enough followup to provoke new ideas for discovering new law-like relationships or to shake up world views of the time. But in the middle ages, enough “tinder” was set and waiting, that this time it kindled.

Merv,

It is interesting to consider the history and science (if any) for the Byzantium empire – they had all of the Greek (Hellenistic) knowledge and also Christianity. Yet I do not think they advanced in what we term science to the extent the West did. The reasons for this are very complicated and I do not think they can be reduced to what Christianity did or did not, and certainly atheism had a virtual zero impact on such advancements.

GD

Part of the story, at least, is that Islam co-opted both the literature and the staff. I was interested in a recent (sad) news item about the eviction of Christians from one town in Iraq, by Isis, to hear it stated that Christians from there had been amongst the scholars contributing to Islamic science in the early centuries. It seems in the 7th century Christian Iraq had a near-monopoly in medicine, philosophy and Greek literature, and produced giants like Hunayn ibn Ishaq, an Assyrian Nestorian.

After Constantine it’s easy for us Westerners to forget that the cultural centre of the Empire was Constantinople and all points east. Rome was a backwater, and that showed when the East became preoccupied by, and then conquered by, Islam.

One could say that Islam was a late beneficiary of Byzantine knowledge as early-modern atheism was of Catholic and Reformation learning.

Jon,

History is full of interesting and illuminating information that would help us understand ourselves and individuals and communities – and civilisations are to me an endless and inexhaustible source for wisdom.

On the topic, I am impressed by the efforts and fruits of Medieval Scholasticism, and I am inclined to the view that this (if we can identify one major cause) has a lot to do with the Western advances in science – but not the only cause.