There’s an interesting take on the historicity of Adam on the Colossian Forum, as part of a project funded by BioLogos, Beyond Galileo – to Chalcedon: Re-imagining the Intersection of Evolution and the Fall, of which at least one of our readers, J Richard Middleton, is a participant.

The piece, by Aaron Riches, is interesting in critiquing a major strand of BioLogos’ own position as being tarred by the same brush as Biblical Creationism. Both, he suggests, are tied into the same unwitting subservience to the supremacy of the modern scientific paradigm, a criticism I’ve made myself. BioLogos has disowned scientism in the past, but we are all susceptible to its soft form, in which we do not claim that only scientific truth is valid, and yet default to it as the principal arbiter on most questions – this is the spirit of our age.

Aaron’s position on Adam is hard to appreciate coming from a scientifically biased background. It is easy to misunderstand him as denying the validity of science, but that is not his position at all. Rather, he is saying that the reason that informs faith (and that is presented to faith by Scripture and the world) encompasses much more than the limited epistemology that science affords. In particular, especially with regard to Adam, it is our resonance with the personal that is key.

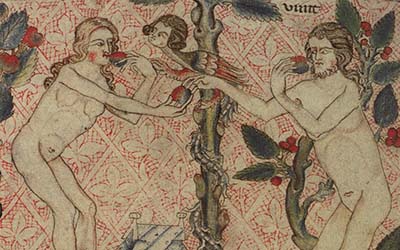

He begins with the central fact of Christian experience – the personal incarnation of Christ. In Paul’s discussion of Christ’s ministry in Romans 5, it is the person of Jesus who is central, but it is also the person of Adam off whom the discussion bounces: the origin of our sin is as personal as the origin of our salvation, and should not, and cannot, be reduced to mere metaphor. This, he says, is why Genesis begins the revelation of God with the account of an actual person.

But how, we might ask, does this deal with the criticisms of an Ayala, a Venema or a Falk that genetics does not allow us to admit a single pair as the ancestor of humanity? The essay makes no direct attempt to answer that, but that’s not because no such accommodation is possible, but rather because it’s not desirable. After all, whatever else an actual Adam is, he belongs somewhere in history, not in science. If a single human once invented the bow and arrow (which is not impossible), that fact would be quite invisible to archaeology. In fact, with uncommon exceptions archaeology can tell us little about the human importance of individual lives – even dating a rich bronze-age burial to the exact year would not tell us what made the person buried worthy of this honour.

There are a number of ways that Adam might be accommodated to the scientific story – I’ve even suggested some of my own. But that’s not Riches’ point. Instead, within the life of faith, we should view Adam as we were intended to view him, and not let one particular aspect of experience – our current genetic models – overturn the rest of human experience.

There are a number of ways that Adam might be accommodated to the scientific story – I’ve even suggested some of my own. But that’s not Riches’ point. Instead, within the life of faith, we should view Adam as we were intended to view him, and not let one particular aspect of experience – our current genetic models – overturn the rest of human experience.

Trying to get a better handle on where Aaron Riches is coming from in this, I was particularly helped by his link to a piece by an Orthodox writer, Jonathan Pageau, which I found resonated with ideas I’ve also had over the last few months. Pageau too is open to misinterpretation (and was soundly misunderstood by a number of scientific readers in the comments). But what he’s saying is not so much a critique of science as a presentation of the case that we are in danger of losing touch with the primary level of reality as we over-stress the instrument-based scientific picture that has developed since Galileo.

As I suggested at the close of my recent piece on postmodernism, the primary level of experience, shared by all men not only now but in all times (and even by the animals) is the level of the sensory, the phenomenological. Pageau, too, suggests that whenever we look away from the telescope and the supra-sensory insights of that and other instruments, the world is flat, heaven is above us, we confront each other face to face – and this level of reality is where most human meaning is to be found.

Don’t conclude he’s trying to return to a mediaeval science – as he says, the mediaevals well knew the world was round, but in daily life even with that knowledge, the world is experienced as flat, the sun rises and sets, and so on – and there is real meaning in all those un-mediated sensory experiences.

I’m reminded of Arthur Eddington, who defended the mundane world before an imaginary tribunal of scienists (he was himself a ground-breaking astronomer, of course):

My conception of my spiritual environment is not to be compared with your scientific world of pointer readings; it is an everyday world to be compared with the material world of familiar experience. I claim it as no more real and no less real than that. Primarily it is not a world to be analysed, but a world to be lived in.’

This doesn’t dismiss the scientific, but does, as it were, rehabilitate the world of daily experience, as Pageau does, as the place where we should most seek meaning and significance. A few weeks ago, before reading either Riches or Pageau, I’d thought of doing a piece with this general theme.

Imagine a great film you enjoy on TV – one with a message of the most significant human emotions, moral content and so on. It may be pretty instructive to study how the director has achieved his impact through his the script, the cinematography, the sound and so on. It may be interesting to understand the financial and political struggles that brought it to the screen. It may even be valuable to go deeper and understand the various scientific and technical aspects of film-making and TV.

But what is the film, really? How is it meant to be experienced? Miss the human impact intended by the director, and everything else is relatively unimportant. So then, what is God teaching us about in Adam, at every important human level? That’s the big issue. The “how” of Adam is well down the list of priorities.

It’s still an individual matter if the Fall happened personally to a whole lot of people rather than just two. If the plan of salvation existed from the beginning, not as a contingency plan but as a certainty necessity, then whoever came to moral-spiritual capacity was going to soon blow it and need saving. I don’t know when, where and to whom it came about, and I can’t see any way we can find out, but I think the essence of what happened is described in Genesis.

Pngarrison

I think it’s a risky thing to argue from a plan in eternity (one that, indeed, is represented in Scripture as a secret within the Trinity even the angels did not know) to a general necessity in time; ie “There was already a salvation plan, so sin was bound to happen some time.” Would one argue that God’s “set purpose” in Acts 4 that Jesus would be betrayed was that human nature was so corrupt that someone or other was bound to betray him, rather than being linked to eternal foreknowledge about Judas?

More generally though, I’m unconvinced by the arguments usually given for a “generic and corporate Adam”. The article cited in the OP has as its main concern treating Scripture as a separate epistemological source not subordinate to science. But there are separate concerns too which, in my view, affect vital truths about Christ and the gospel.

For starters, I see no evidence that, in its ANE context, Genesis could be interpreted as teaching a racial or allegorical fall through an individual one. I know of no examples of such “Everyman” metaphors in the ancient literature – as indeed John Walton confirmed to me in an e-mail. Adam can be an archetype, but that in the ANE implies an individual, whether real or believed to be real. So Genesis cannot be deliberately using Adam as a metaphor for something general; it must be simply mistaken, if Adam was not an individual.

Then we come to the use of Adam in both Old and New Testaments. The few OT references are individual, most notably the 1 Chronicles genealogy. But the NT references are much more clearly so. I have yet to see a convincing case that Paul’s argument in Romans 5 does not depend for its force entirely on the comparison between two actual individuals and their bequest to us. But the same individuality applies to Paul’s use of Adam in 1 Corinthians 15, and his use of Adam and Eve in 1 Tim 2.11ff and 2 Cor 11.3. But Luke, too, implies an individual in taking Jesus’s genealogy back to Adam. If we also include the widespread use of Edenic imagery, such as the description of Satan as a serpent (and the use by both Jesus and John the Baptist of the Genesis-rooted “seeds of serpents” for the wicked), then the Biblical case for an individual person, albeit it with room for much valid interpretation regarding anthropology, biology and so on, is strong.

If Adam was not in fact an individual, that implies that the apostolic authors are, too, merely echoing the false beliefs of the Genesis author, which entails a certain view of Scripture. The easiest move is to dismiss inspiration altogether, but that is not the current line amongst those under the Evangelical umbrella, where a “kenotic” view of inspiration is embraced: that is, that as God’s word is given to man, it is emptied of much of its divine content of truth, and takes on the human characteristics of pervasive error. Naturally, discerning what remains of God’s truth is also a human, and necessarily error-prone process.

This, needless to say, is entirely alien both to the testimony of Scripture about itself and the judgement of historical theology. It was the supernatural authority of God’s revelation that was stressed by the prophets (“Thus says the Lord…”) and the apostles (“we do not speak with words of human wisdom…”) as well as the Church in Patristic, Mediaeval and Reformation times. But it is not surprising coming from those who take a similarly kenotic view of Christ’s incarnation, in which the humanity is stressed over against his divinity in a way very reminiscent of some of the views rejected by the Council of Chalcedon.

Nearly every possible trick had been tried in early centuries to resolve intellectually the difficulty of the eternal Word’s becoming man. Many stressed his divinity at the expense of his humanity (eg docetism, adoptionism) and others his humanity (eg Ebionism), with Arianism striking a middle path by effectively rejecting both.

But the orthodox emphasis of Chalecedon was that his “kenosis” was not any loss of divinity, but the taking on of created flesh by divinity. Even in his death he was still the ruler sustainer of the Universe – how much more so in his life, since the cosmic order was maintained. So his “Very truly I tell you, we speak of what we know, and we testify to what we have seen, but still you people do not accept our testimony” was not hyperbole. What he taught about the altar making the offering holy, rather than the gift polluting the altar, was also true of him.

Furthermore, the human nature he assumed was that of a New Adam – mankind as created, in perfect communion with God, and not as fallen. To speak of Christ’s participation in human error is to deny this ancient testimony (perhaps sometimes by the circular assumption that since there was never an unfallen human nature, Jesus couldn’t have assumed it).

As Athanasius says:

Now historically the Church took its view of inspiration from this high view of incarnation, both of them being perceived by faith in the Word who is the divine source of both truths. In my view the other view of incarnation, and hence of inspiration, and hence of the reliability of the Adam “corpus”, depends on conclusions derived from human reasoning and investigation. Accordingly, I personally find it impossible to accept.

Do you think inspiration implies inerrancy? Most of the Christians around me have insisted on this all my life, but I don’t think it necessarily follows. It’s understandable that Christians thought something like that for a long time (and most? still do) but inerrancy seems indefensible to me at this point.

You accept that evolution happened and that is a conclusion from human reasoning and investigation – it certainly couldn’t be predicted from anything in Scripture. If you don’t think the point of Genesis 1 was to provide scientific knowledge, you could say that evolution doesn’t conflict with Scripture. (You would have J.I. Packer on your side.) I don’t know offhand what you think about the Flood or language differentiation at the Tower of Babel. It has long seemed to me the those stories are even more difficult problems for the inerrantist than Genesis 1, since they plainly claim things happened that should have effects on what we observe today that are not in fact seen.

It seems possible to say that the incarnation/inspiration involved in producing Scripture is different than the central Incarnation, since, unlike Jesus, the prophets were sinful men, even if inspired. If they express or assume the beliefs of their culture, that needn’t compromise their report on spiritual matters.

Personally, it seems more likely to me now that even Jesus took on the incidental beliefs of his culture and the non-moral/spiritual imperfections we all suffer. In what sense did He live the life that we do if He walked around with His divine omniscience on every subject and practiced carpentry without ever cutting Himself or hitting his thumb with the hammer, if He never made an innocent mistake in any respect? It seems akin to the temptation He was offered in the wilderness to reclaim His Heavenly prerogatives before His mission was done.

On the original question of Adam, I don’t know what the truth is. It certainly doesn’t seem possible at this point that the human race descends from a unique couple at any reasonable time in the past. The possibility of Adam and Eve being one couple among a population, with only their descendants being fully human makes no sense to me. Their descendants would be confronted with how to treat the sub-humans who looked like them, made a living like them, possibly talked like them. How would they even tell for sure who was fully human and who wasn’t? If they could tell the difference, would it be o.k. to treat the sub-humans like animals? If they were in the middle East, you end up saying the people in the rest of the world weren’t fully human – it sounds like 19th century racism. (There is an anthropologist in Russia who claims something like this – surprise, surprise, the “real” humans were in Russia.)

I can see the possibility that a representative couple lived something represented by the tale of the garden, and what they did then had consequences for everyone else who also then became fully human.

As for what depends on human reasoning, I don’t see how we can separate out what does and what doesn’t, except by the insight that the Spirit gives us. In a real sense, everything from every human, prophet or not, other than Jesus, depends on human reasoning to some degree. Whatever God revealed to them came through their human experience and thinking. It bears the mark of their culture and their individual personalities. The same is true of the church fathers. I don’t think we can sort out human reasoning and divine message just by looking at the source.

pngarrison (btw, if you’d rather be called by your given name, let me know):

You make many good points. One of the problems is that the term “inerrancy” is slippery. I’ve seen it used to mean everything from absolutely strict historical reading of every past-tense prose sentence in the Bible, to a much broader notion, e.g., that the Bible is without error in all that it teaches , where the word “teaches” creates more interpretive space. (For example, the Bible may incidentally represent the world as stationary, in line with common conceptions of the day, but it does not follow that the Bible teaches that the world is stationary, in the way that it teaches things about Moses or Jesus. Thus, the Biblical representation of the world as stationary would be an error, but not an error that threatens “inerrancy” in the religiously important sense.)

Of course, often people are concerned that errors are blasphemously imputed to Jesus. But again, what kind of error should we be concerned about? Errors in geography and botany? Or errors in religious teaching? Could Jesus perhaps make certain kinds of error, but not other kinds?

If we take the Trinitarian discussions seriously, then Jesus is not only fully God but also fully man. And if he is fully man, then he doesn’t, any more than any other Galilean peasant, know the theory of relativity or how stars were formed — even though as Logos he was also there during creation. For him to be fully human, while he may be in a sense conscious of the divine nature within him, I don’t think he can be in daily possession of the divine knowledge of nature and history that God has. He would not be able to live and act truly as a human being if his human body housed the conscious omniscient mind of the Creator. To act humanly, you must feel yourself to be human, not a God in disguise. And indeed, at least in the Synoptic Gospels, Jesus speaks as if he conceives himself to be a man who does not know all that God knows, either about nature or human destiny. He may of course have flashes of prophecy, but not total knowledge of past, present and future. (Otherwise we would have Docetism, and Jesus would be something like Krishna.)

I would say that Jesus held the normal beliefs of Galileans of his day about the shape and motion of the earth, the causes of thunder and lightning, etc., as opposed to ideas such as were found in the Greek philosophy of his day, or the science of our day. That is, he believed some things about the structure and order of the world which are false. But I don’t think it is blasphemous to say that. If he is really human, and not just a God pretending to be human, he is subject to the same intellectual errors as other human beings. So it’s far from blasphemous, but a consequence of the Trinitarian notion of “wholly man” or “fully man,” to make Jesus the Galilean carpenter partake of human ignorance.

But there is a difference between what Jesus says, and what Jesus teaches. Jesus might say or imply, in the course of talking about righteousness or sin or the kingdom of God, that the earth does not move. Yet Jesus is not teaching anything about the earth at that point. He is rather assuming the common view of the earth, and teaching about something else. So he can be in error while his teaching remains inerrant.

I think this applies to some extent even to the Biblical references made by Jesus. Suppose, for example, that Jesus said: “Have ye not read that on the third day, God said … and it was so,” and then went on to draw some moral about the reliability of God’s word and hence God’s promises, to help strengthen the failing faith of one of his followers. Now Jesus may well have believed that the world was created in six 24-hour days. That may well have been the standard reading at the time. But it doesn’t follow that this is the correct reading of Genesis, i.e., it does not follow that the Genesis writer intended anyone to adopt such a belief. The six-day scheme may well serve some purpose other than to convey historical information. And if many of the rabbis of his day did not realize that, then Jesus might not have realized it, either. But it wouldn’t affect his teaching in the context.

His teaching, in the example given, is practical rather than historical. It’s as if he said, “Don’t you remember, in Gone with the Wind, when Rhett Butler …” and then drew a moral from it. It’s irrelevant whether there ever was a person named Rhett Butler, and equally irrelevant whether Jesus knows that Gone with the Wind is fiction or has mistaken fiction for history due to his lack of knowledge of the literary conventions of another era. His point is not to try to convince you that Rhett Butler really lived and did X or Y. Rather, he is simply taking advantage of the fact that you know the story of Gone with the Wind, so that he can use events in that story to illustrate his point. So when he refers to the events of the third day, he is taking advantage of the fact that all of his listeners know the Genesis 1 story, and using that story to teach them something relevant to their current problems. He wants the listener to draw the moral from the story of the third day; whether the third day was actually a 24-hour period or not is incidental. The point is that, given his pedagogical goal at that moment, Jesus would have used the Genesis passage in exactly the same way whether he believed in six calendar days, or day-age, or gap theory, or that the six days were just a literary device . Therefore, his teaching on the point in question, being unrelated to his incidental acceptance of a literal six days, would remain inerrant.

So if it turns out upon study that the Genesis writer did not intend six literal days, then doubtless many rabbis of Jesus’s day, possibly Jesus himself, and many of the Church Fathers (though not Augustine) have made an error. But it’s an error of no theological consequence. It’s not an error in the teaching of Scripture, but in the human interpretation of Scripture. It would be Christian writers who would be in error. But nobody ever said that Christian writers were inerrant in all they taught, so that is not a problem.

Eddie

Your overall position is quite plausible. It is indeed reasonable to say, “If fully man, then (negatively) not intuitively in touch with all knowledge and (positively) in touch with his own culture.”

But you seemed to forget quite quickly the first half of your description, “…not only fully God, but…”. The same reasoning process must be applied to his divine nature. And it would then be reasonable to say, “If fully God, then omniscient.”

And therein lies the mystery of the Incarnation, because we are not qualified to privilege one nature over the other, and we have absolutely no insight into the matter except what Scripture gives us. And as GD points out below, Scripture has plenty of pointers to a more-than-ordinary humanity, as well as to the basic human issues of emotion, fatigue, hunger and so on.

The kenoticists get round it by, effectively, denying Christ’s Godhead (by piss-poor exegesis) and treating him as in practice only human-like-us – a view consciously rejected throughout Church history. But Scripture maintains the mystery in tension: in Hebrews 1, for example, it speaks of the same Son sent to speak to us more excellently than the prophets also “sustaining all things by his word of power.” Now I don’t know how one might accidentally hit ones thumb with a hammer whilst maintaining the integrity of every particle in the universe, but the latter at least, is what it says… but then, how do I know that those bits of Scripture aren’t culturally conditioned too? Perhaps the writer to Hebrews was insufficiently kenotic (or Ebionite) in their Christology. If Scripture is thus relaivized, how will one judge the matter, except by ones own (non-apostolic) culturally-conditioned beliefs?

And Colossians 3 says that “in Christ all the fulness (pleroma) of the Deity lives in bodily form.” It is quite likely that the word “pleroma” is being filched from the proto-gnostics, who sharply distinguished God’s spiritual fulness from the corrupt physical – if so, Paul is making a profound statement about the reality of full divinity in the human Christ. But were the Gnostics actually better informed, Scripture being human and all?

The problem is then that one is logically entangled as soon as one tries to avoid extreme kenoticism by granting some divine power and knowledge to Christ, as one must if by his power he stills the storm and by his coming from heaven he teaches God’s word. Exactly how much more divine than us does he have to be before he’s not properly human? Is there a table of disciplines to be drawn up with theology, morality etc on the “divine inerrant” side, and history, biology etc on the “human errant” side? How dare any human even presume to attempt that if they worship Jesus as God?

But of course, the issue never rests with flat earths (if anybody in 1st century Hellenistic Judaea still believed that) and bent nails. There is always mission creep: if Jesus wrongly believed the Old Testament account of Adam as the first sinner, then his teaching on sin needs to be adjusted. “If you, being evil…” might be a mistaken cultural assumption of his rather than (a) a divine endorsement of the biblical doctrine of sin and (b) a divine knowledge of the state of our hearts.

Hi, Jon.

Yes, fully God as well as fully man — but that is on the metaphysical level, the level discussed by theologians who bust their brains trying to make sense of the Trinity. I’m not denying that is sometimes an appropriate level for discussion of Jesus. But I’m talking about phenomenological level — how Jesus experienced himself, so to speak.

Over and over again I’m told by Protestant apologists that we must accept that God *suffered* for us, *died* for us, and that this God is very different from a Greek deity who is immaterial, spiritual, above the body and all its pains. I’m told that Christianity is not “Greek” but “Biblical” or “Hebraic” and that we must reconceptualize Jesus in that light and cease to overly-spiritualize him. But what if we follow through on that?

Well, the Passion means nothing — certainly nothing “Hebraic” — if Jesus didn’t really feel agony, didn’t really know the fear that mortals know in the face of death. If Jesus is just God in disguise (Docetism), then the Passion is all playacting for him, something his infinite super-powers can easily get him through. He can only experience the Passion *as a man* if he has the limitations of man. But if his body has the limitations of hunger, thirst, vulnerability to wounds, and death, and his soul has the limitations of fear and anxiety, then why couldn’t his mind also have limitations that all men have? Scientific ignorance, historical ignorance, ignorance of what people in China are like, ignorant that there is such a thing as the New World, etc.

I’ve often been admonished to abandon my “dualism” — my allegedly “Greek” view that treats body and soul as quite different things, and to adopt a “Hebraic” view of the unity of man — body, soul and spirit all fused together. Well, if that’s really the “Hebraic” or “Biblical” view of man, and if Jesus really *is* a man, then the limitations of Jesus’ body would go hand-in-hand with limitations of his mind and soul. So he couldn’t be a man while dying for our sins but an inerrant God when talking theology. We do theology with our minds and souls, and if the “Hebraic” teaching is that body shapes mind and soul as much as soul or mind shapes body, then there is every reason to think that Jesus, when reasoning theologically, would reason as an educated rabbi of his day, but still, like them, as a man. Otherwise, it’s back to a kind of dualism, only with a “God trapped in a Jewish body” rather than a “ghost living inside a machine.”

Of course, nothing I’ve said rules out the possibility that Jesus could know things the rabbis didn’t, if he was inspired by God. But if he was inspired by God 24/7, and inspired with the fullness of God’s knowledge 24/7, then he *would* know the theory of relativity, etc. After all, he was the Logos through whom the physical universe was made, and if he knows he’s the Logos, then he knows the theory of relativity. But such a Logos is too far above mortality to pose credibly as a humble, suffering Jew. So he mustn’t know he’s the Logos, even if he is aware of being somehow closer to God than other mortals.

Are you arguing that Jesus at all times understood himself to be identical with YHWH, creator of the universe, and had all the knowledge of all that YHWH had ever done, and all the knowledge that YHWH had of the future? So that he walked around understanding the biochemical secrets of life and relativity and quantum theory, but chose not to talk about those things because they wouldn’t be understood in his era?

If so, then forget all that stuff about getting back to a more earthy, Hebraic Jesus, who because he has suffered like us, “understands where we are at,” and can stand in for us. A 5 ft. 6 in. Palestinian Jew who walks around thinking — no, *knowing* — that he created the universe and can blow it out like a candle at will is simply not credible as my suffering representative. I’d take someone like Mother Theresa any day. She really *would* know how I feel, what I fear. She lived with fears and doubts herself.

Or are you saying something different? Are you conceding that Jesus didn’t walk around 24/7 thinking “I’m God”, but still affirming that Jesus had fits of *temporary* knowledge that he was God, before lapsing back into self-induced forgetfulness so that he could resume the role of suffering servant and relate to the common man? So that when someone asked him a

a religious question, he suddenly recovered his YHWH memory of creating the universe ex nihilo and his YHWH knowledge of the future, but when someone asked him where the sun goes when it sets, or if there are people at the Antipodes, he becomes ignorant again and genuinely had no more idea than his fisherman or carpenter friends?

Such a Jesus would be a sort of Jekyll and Hyde, sometimes with one personality and self-conception, sometimes with the other; and like Jekyll (at least as Jekyll was at first) unaware of the activity of his divine (in the case of Hyde, demonic) side most of the time. So (corresponding with the humility of Jekyll) he would normally think of himself as a mortal who has been “adopted” as God’s son (at the Jordan), and as nowhere near as great as the Father, but every now and then (corresponding with the boldness and assertiveness of Hyde), he would pop out with statements like “Before Abraham was, I am.” God and man would alternate as if their appearances were controlled by a sort of spiritual “toggle switch.”

But perhaps that is not your view, either. But then, if we eliminate the view that Jesus walked around 24/7 knowing that he was YHWH, and if we eliminate the view that Jesus had fits of knowing that he was YHWH, what would be your view of the state of knowledge of Jesus, and of the self-concept of Jesus?

These questions aren’t based on mere metaphysical speculation on my part. I haven’t even started on the Biblical side. There are scores of statements in the Gospels — the few Johannine statements that don’t fit are decidedly in the minority — that indicate that Jesus’s self-consciousness was that of a mortal man. He thought of himself as having a special role, yes: as “Son of Man” and as “Son of God”; but he was always saying things like “The Father is greater than I” or “No man knoweth the time of X, only the Father” — the implication being that he, Jesus, didn’t know the time of X either.

We are told that Jesus prayed. Well, if his self-consciousness was 100% that of YHWH, praying would be idiocy — indeed, psychologically impossible. Under any straightforward reading of such passages, Jesus was praying to God, conceived of as distinct from him, as God is distinct from all men (which Jesus would have had drilled into him as a Jew), and as a father is distinct from his son. And when he asked that the cup be taken from him, that would be a totally insincere request if he knew fully that he was divine and could walk away from this Passion business any time he wanted to. Who is making him take the cup, other than himself, if he is God and planned the whole economy of salvation?

When he said that he was commending his soul into the Father’s hands at the end, he was surely speaking as man and a Jew, not as the Creator of the Universe doing some “slumming.” Otherwise the whole Passion narrative reeks of falseness.

So I think that, even if we completely set aside Trinitarian formulas about Jesus’s humanity being real and genuine, even if we just stick with the Biblical text, we have a Jesus who speaks, acts and feels like a mortal, who doesn’t know everything, not even everything about religious matters, and who can feel fear, anguish, humiliation, etc. That’s what I see when I read the Gospels. That what I saw when I was in Sunday school as a child, and that’s what I still see when I read the Gospels in the light of Greek and Hebrew study, historical study, literary study, etc. I see a man who understands himself, on the conscious level anyway, to be a man, however much he is aware of some deeper knowledge and power which he has access to when he heals, and no matter how much he feels himself to have been given special responsibilities by God. He is aware of himself as a *special* man, as a man who walks with unusual closeness to the divine — but still a man.

Of course, the knowledge of Jesus after he ascends to heaven — that’s another matter. But then he has abandoned the limitations of “Jesus” — Jew, carpenter, Palestinian, first-century, no schooling beyond what was necessary to read Hebrew in the synagogue, vulnerable, mortal, bad-tempered about fig trees, etc. –and become once again the pure Logos, the Second Person, the pure Son. Then his knowledge is identical with that of the Father. But not while he’s on earth. Or so I interpret the Gospels.

The foregoing is the basis for my thoughts on “Jesus as Biblical interpreter.” But of course I have not yet drawn any conclusions about how Jesus reads the Bible. I have not said that Jesus’s reading of the Bible will yield any errors. I’m just laying out my basic axioms. I’m saying that when he reads the Bible, Jesus doesn’t say to himself: “I know what this Book means, because I’m the one who wrote it.” I’m saying that he reads it as a pious Jew, albeit one with a special connection with God.

If I post anything further on this, it will be on the subject of what it means to read the Bible as a pious first-century Jew. Any limitations that Jesus might have as an interpreter would be related to that. But this is not an Ennsian “incarnational view of Scripture”, nor is it a Murphyan “kenotic” view of God. It’s simply taking seriously what the Bible teaches, i.e., that Jesus was born, lived, and died as a Jew, and what the Trinitarian doctrine insists on, i.e., that Jesus’s “mannishness” was real and ran to the core of what he was (as Jesus of Nazareth, carpenter and part-time synagogue preacher), and therefore was bound to shape all that he did and felt and said — including his exegetical activity. Be the Scriptures as perfect as the most diehard

Reformation Protestant would insist upon, they still have to be interpreted, and all human beings bring their peculiar personal version of humanity to that task. Jesus would have done the same.

Well, I’m not much into the “suffering God” theme – Patripassarianism was another of those beliefs the Fathers had to deal with.

Personally, I think people attribute to Hebrew thought what Hebrews never did, from that well-known 20th century exaggerated dichotomy of “Hebraic” v “Greek” thought that enables “modern” thought to gain some ancient authority.

Yet if one ignores metaphysics, one has even less grounds for speculating on the unique Son of God and his being. Who he is is crucial to salvation – what that was like for him is not, or he would have taught it to us.

What the orthodox doctrines work hard to stress is the unity of the divine and human natures of one Christ, and yet their distinctness. He was fully God and fully man, not a mixture of God and man, and still less one at the expense of the other.

It was Christ as a complete unity who suffered, but he suffered in his human nature not simply for Platonic reasons of the impassibility of God, but because it was the human nature that needed redemption. And yet it was an identity of the divine Word of God in our suffering – for unlike some of the heresiarchs said he did not withdraw happily whilst a human victim suffered. In that sense, and in the effect on the divine communion, God might be said to have suffered.

Now those orthodox teachings are already pushing the boundaries of comprehensibility, and so I say that in the absence of any teaching of Scripture, nor any conceivable comparable example from which to extrapolate, anybody who uses reason to say what the Lord’s mental life nust have been like has gone too far.

This is one of the genuine mysteries we accept by faith, as opposed to the kind of impasse some of the modernists get into by speculating incoherently. And as a nystery I intend to leave it.

Jon:

I agree with many points in your analysis.

On some particulars, I understand Patripassianism to be the doctrine that God as the Father suffers. Much could be said about that — there might be a *sense* in which the Father suffers but it is a not subject that I would lightly speculate on, without doing more study. In any case, I wasn’t claiming that the Father suffers; I was claiming that the Son — in his mortal career — suffers.

I agree with you that the Hebraic versus Greek conflict has been greatly overplayed. My complaint there was really against theologians who bash dualism when they think they don’t need it, but slyly slip it in when they think they do need it. One can’t preach loudly that human beings are psychophysical wholes, but then say that Jesus, even though he was a real human being, wasn’t a psychophysical whole, but a sort of yoking of a divine mind to a human body.

I don’t think we have to speculate very much about the interior life of Jesus on the points I’m raising, since the Gospels give us much evidence on that point.

For example, the Gospel narrator tells us that Jesus prayed. And unless the Gospel narrator is trying to mislead us, that means the same thing as it would if the Gospel narrator told us that Peter prayed, or the high priest prayed, etc. To a Jew, praying means addressing God as someone distinct from oneself, and vastly superior to oneself in the power to give one what one most needs for body, soul , and mind. So I infer from the words of the narrator that Jesus regarded God in that way. I don’t see any reason to block such an inference on the grounds that the ultimate nature of Christ or of the Trinity is a “mystery”; I’m not claiming to have a full understanding of all the thoughts and feelings of Jesus. I’m merely pointing out that “Jesus prayed” is not compatible with any teaching that suggests that Jesus walked around thinking of himself as YHWH.

Eddie

An interesting quote from Dietrich Bonhoeffer on the “Church perverted by Greek thought” trope:

I think every reader of this thread could do worse than to review the documents of Chalcedon, and especially the Tome of Leo which is its backbone, here.

The only drawback is that one fails to appreciate just how many serious errors (or “fatal exceptions”!) had pervaded the Church,and in the case of Arianism even dominated it for a while, through putting reason before revelation. To which another quote from Bonhoeffer is relevant:

In his day he had in mind the liberal Church’s compromise with Naziism, I suppose. But now many Evangelicals would regard him as a bit of a dinosaur:

Eddie, sorry I didn’t reply earlier. I think we pretty much agree here.

I don’t mean to be saying that I know what it was like to be Jesus when He was here, but there are some remarkable clues in Scripture. He “grew in wisdom and stature” – the first part of that is pretty mind boggling if you think He was fully God. He was “tempted like as we are.” He clearly really felt hunger, thirst exhaustion and pain like we do. I think it is reasonable to think that He got the occasional cold, etc.

There’s no question among us of any doctrinal error on Jesus’ part. The question is what about human imperfections and limitations that have no moral-spiritual component. I assume, being perfectly focused and disciplined He was a fine student as a child, but does that mean he never did a sum and got it wrong at first? No one can know for sure, and it bothers some people to think He might have, but it seems possible to me. If you haven’t faced even the possibility of frustration at your limitations, have you really been “tempted as we are?”

I think the question of what “incarnation” of the Word means in terms of inspiration of Scripture is the more pressing problem, because we are faced with the problem now that certain statements and even whole stories in Scripture seem to conflict with observations, if those stories are taken in the plain literal sense that they have historically been taken, and that in all likelihood was the intention of the original human writers.

I think the value of science for Biblical studies is that it can shake us loose from long standing conceptions that were really a distraction from what the prophets and the Spirit were actually concerned about.

From Peter Enns blog post today. Seemed relevant.

“By using the incarnation as an analogy for the Bible, no claim whatsoever is being made that the Bible is a “hypostatic union” or other language normally reserved to describe the incarnation of Christ. It is an analogy, not an attempt at identification.”

Hey PNG,

I have given this link out before, but I do enjoy reading it and his take on Adam and Genesis. Let me know what you think.

http://drmsh.com/2012/07/26/genesis-13-face-compatible-genome-research/

Hanan, I had looked at that when you posted it before, although I haven’t gone through all the comments. Something like what is proposed there seems reasonable to me. I like the idea of a representative couple – he seems to imagine them as specially created, but it makes more sense to me to think of them chosen out of that surrounding population. If they were specially created they would have to be made to look genetically like some particular population. There’s not any unique lineage lurking among us that’s completely distinct from everyone else.

What doesn’t make sense to me is that he sees the non-Edenic people as being sinners simply because they are human – it seems to mean sinfulness is part of the definition of humanity, which creates obvious problems for the Incarnation – a Fall that affects everyone seems necessary. If Genesis is really describing two difference creations of humans, it gives no explanation of why the non-Edenic humans should be born sinners. It makes more sense to me that their sin is the consequence of Adam and Eve’s sin. How that would work out in detail I don’t know.

For something to be sin, the person has to be aware of “the law,” the fact that they are doing something wrong. It may be that such knowledge came at different times for different cultures and individuals, and the fact that they would fail the test was determined by Adam and Eve’s original failure.

Of course we always have the problem of how God deals with the individual who dies never having known sufficiently about right and wrong or about Him; the child who dies, the person raised by abusive sociopaths, the feral child (this category is really weird – google search it,) the tribesman, ancient or modern, who lived his whole life in a culture of warfare and revenge. I assume that if we knew what God does, we would find it merciful.

Hi PNG

Regarding your first paragraph, I think it is safe for me to say that Dr. Heiser does not necessarily (though not outright against it) believe in a real foundational couple. That essay is him bringing up an idea of Adam and Eve specifically being an archetypal story for the election of Israel later on. Just like Israel is elected amongst the masses so are Adam and Eve. This idea comes out in a Psalm where the the composer talks about the Children of Man and then the Children of Adam, appearing to make a distinction.

For further reading you can read this as well as to how evolution plays in. Don’t get bogged down by his comments on evolution. Just continue reading to where he actually discusses Adam.

http://drmsh.com/2012/06/02/evolution-adam-additional-thoughts/

You can always email him regarding your other questions. I find the man to be brilliant in his analysis of the text. I am sure he has responded to questions like that.

Preston

Clearly there is a difference between incarnation and inspiration (but then it isn’t me who uses the term “incarnational” for Scripture). But the incarnation is, at least, the limiting case, in that if Jesus himself were capable of doctrinal error, then the rest of Scripture doesn’t have a leg to stand on.

But the emphasis in Scripture itself is not on the recipients of inspiration, but on the Source. God speaks to Moses, and his face shines, rather than God’s dimming. If it’s a question of a human effort to understand God, then the watchword is fallibility. But if it’s a question of God choosing to speak through men, it’s a question of sovereignty… the same sovereignty that promises perfection through grace to universally-sinful people like us.

So Hebrews contrasts the prophets with the Son in 1.1-2, but in both cases refers to God speaking to men through them – the excellence of the Son’s ministry does not diminish the reliability of the prophets, for he builds his entire doctrine about Christ thereafter from assuming the truthfulness of the Scriptures he cites.

Now understanding genre, culture and authorial intent are important, as not only Jim Packer but William Tyndale stressed in talking about the “literal meaning”. But “error” is a big word to use of Scripture since it entails sitting in judgement on it – and on its Editor in Chief. I have to know that I know better than the authors “carried along” by the Holy Spirit of Christ in them – I teach the Teachings.

Given the historical situation, I also have to say that I know better than two millennia of catholic orthodoxy – indeed that the very basis on which those guys argued through to the theological concept of Incarnation and stressed its centrality (the authority of Scripture v. the errors of the heresiarchs) was wrong. Apollinaris and Athanasius stand in equal ignorance, and the arbiter is Western critical scholarship in the form it happens to take this year.

If it’s not surprising that previous generations considered the Bible without error, it’s even less surpring that those brought up with Modernism and Postmodernism should deny it. It’s culturally conditioned, but far more myopically so than any previous generation, because it elevates itself above all prvious generations.

Now it may well be that Jesus made slips of the tongue or of the saw – but if so his apostles don’t record them. And since there is no other account of a perfect human life (the eternal Image of God conformed fully in the created image, conceived by the Holy Spirit, born of a virgin, well-pleasing to God, raised to glory at the Father’s right hand…) then it is something on which anyone is incompetent to speculate. We don’t even know unfallen Adam’s psychology – are we competent to pronounce on the God-man? Certainly, as soon as we insist he had, on some principle of absolute identity, to be like us in our failures, to be conformed to cultural errors and the like, then we have no grounds to exclude sin either – we have only his say-so, and that of the same witnesses who gave us Scripture, that he is sinless. Perhaps God has the same limited success with the embodied Word as with the written word… or perhaps he doesn’t in either case.

It’s not just that Jesus “must” have believed in a Young Earth and ergo “must” be capable of intellectual error to be fully human: it means that when he backed up his teaching with “Scripture cannot be broken” he had his whole doctrine of inspiration wrong (even though it was his own Spirit, without measure, that had done the inspiring). No less misled was John, who thought he was inspired by the same Spirit to write the Lord’s words into Scripture.

Problems with the Flood or the Tower of Babel? We learn by what they teach as God’s word, and wait patiently for any correlation with current wisdom on … probably not geology and linguistics, if the work on the creation narrative (that has suddenly made all that irreconcilable “conflict” with science pretty passé) is anything to go by.

“it’s even less surprising that those brought up with Modernism and Postmodernism should deny it. It’s culturally conditioned, but far more myopically so than any previous generation, because it elevates itself above all previous generations.”

Jon, you’re accusing scholars of coming to their conclusions just to fit in with a culture, and not because of their own study of the details of their discipline. A famous IDist once insinuated to me in person that that accounted for what Francis Collins had to say about evolution – he was just protecting his prestige and his grants. (I had resolved not to let him make me angry, but he succeeded anyway.)

At least do them the courtesy of accepting that they think for themselves, and deal with the textual evidence rather than making accusations of just following the herd. You’re accusing people of being cowardly conformists. They could just as well say that your perspective is a product of past fundamentalist-evangelical culture. Both are irrelevant observations as far as getting to the truth of the matter.

It looks pretty unavoidable to me at this point that there are trivial contradictions and errors in Scripture, despite all the special pleading to try to account for them. It’s easy to see that the Flood and the Tower and Jonah are great stories that could be there just to teach the ancient Hebrews and us about the sins we are prone to and the judgements that will follow. But coming up with a didactic reason for Kings and Chronicles giving different numbers and other details seems harder. If every apparent error or contradiction in a seemingly historical account is accounted for by some didactic purpose, what did inerrancy ever amount to? It seems to me that it is something that Scripture never explicitly claims for itself, and there might be a reason for that – that it’s not the relevant kind of perfection to describe Scripture. It has been assumed to be a necessary corollary of God’s perfection, and I think part of the motivation has been the feeling that we really, really need a perfect book (Jews and Christians are not the only ones who have felt that way,) so God must have given us one.

I concluded a long time ago that the little song that tells us we know Jesus loves us “for the Bible tells us so” has it backwards. We take the Bible seriously because it tells us a story about Jesus that is so compelling that it refocuses everything, and we find Jesus ourselves. Plenty of people have been saved without picking up a Bible (plenty of them couldn’t read.) They just heard a story or even just a call to repent and ask for forgiveness. An inerrant library wasn’t necessary.

I just sent you privately the story of a man who actually came to believe in the existence of God when he realized that Jesus believed that there is a God. That temporal order of beliefs is unique in my vicarious experience, but I think it reflects an essential truth. We don’t believe in Jesus because of miracles (which we didn’t witness) or because we have a perfect book or because of an apostolic succession. We believe because the Spirit revealed to us the truth about Jesus, using whatever words or people or thoughts were available and attracted us to Him. Someone could say that this is completely subjective, or we could say there really is a Holy Spirit and He really does lead people to God’s Son. The New Testament is the major tool but not the only tool for that.

“as soon as we insist he had, on some principle of absolute identity, to be like us in our failures, to be conformed to cultural errors and the like, then we have no grounds to exclude sin either – we have only his say-so, and that of the same witnesses who gave us Scripture, that he is sinless.”

Jon, this is the slippery slope thing. Saying one thing doesn’t imply saying the next, although someone usually will. The truth is going to be on the face of some “slope,” because people do draw conclusions that don’t follow and wander off. Even if the truth is metaphorically taken as the top of a hill, that is an unstable position, too. There is no ultimate security in the text or in its doctrinal summation by a community. The only real security in the reality of God Himself – that there is a Spirit who will lead us into all truth. It’s good to be cautious about innovations, since we are sheep who tend to wander off, but the Pharisees were cautious, too cautious, and missed what God was doing.

Jesus said that the Spirit would lead his people into all truth, but He didn’t give a timetable. Just because a perspective is old doesn’t mean it has to be true, and of course the same is true for the new.

“the creation narrative (that has suddenly made all that irreconcilable “conflict” with science pretty passé)”

It only became passe’ for those willing to consider that it might have an intention other than giving a literal historical account. As a literal account, it’s not error free, and it was certainly taken as a literal account by countless faithful people for millennia. If one grants this about Gen. 1, it seems to raise the possibility that just because the fathers and everyone else agreed on what other parts of Scripture were doing, doesn’t mean that that they were right. The Spirit might not have finished leading us into all truth in 500 A.D. or 1600 A.D. I doubt that He has now.

Preston

Your first comment, on scholars thinking for themselves, presupposes that it’s possible to think outside the bounds of ones culture. And though it’s not easy, I agree it’s possible – though devilish hard to know at what points one is operating under the errors of ones culture unthinkingly.

But if that is so, then one must grant the same possibility to those theologians of old, and even more to those who wrote Scripture under the guidance of the Holy Spirit, and supremely to the Incarnate Son of God as he indwelt first century culture.

Agreement on doctrine (including that of Inspiration) over millennia of cultural change is actually one of the safeguards against buying into the transient spirit of the age.

It only became passe’ for those willing to consider that it might have an intention other than giving a literal historical account. As a literal account, it’s not error free, and it was certainly taken as a literal account by countless faithful people for millennia.

I would say it became passé for those willing to treat it as an authoritative text and look for the true “literal meaning” in its original setting rather than relativise it from a modern objectivist viewpoint as “obsolete science” or “primitive myth”.

It’s not quite true to say that faithful people have treated it as “literal” for millennia, because the criteria for “literal” have moved with the culture. Usually the faithful have assumed a more or less culturally acceptable view of its literality, and searched for the spiritual significance within that.

Up until now, the text has proved pretty robust in that respect, turning up comparable doctrines of creation, sin, death, the divine image, and so on whether influenced by Platonism, Renaissance Humanism or whatever.

It’s also a moot point if containing “errors” under a modern view of what constitutes literalism makes it erroneous under its own frame of reference. More on that in a forthcoming post.

What worries me nowadays is that the modern cultural assumptions are so often made dominant – for example, in that whole range of evolution-based theologies that re-interpreted the Eden story as far as was possible in a Promethean sense of a fall upwards to greater spiritual knowledge, attributing whatever didn’t fit to ancient ignorance of the Darwinian narrative.

Finally, a recourse to the governing hand of the Spirit, over against Scripture or other sources like orthodox tradition, as the arbiter of truth, puts one in the difficult position of having to conclude that those who disagree with one aren’t listening to the Holy Spirit right. I agree that’s no more of a problem that drawing different conclusions from Scripture, but it’s no less of one either.

In my case, for example, the single most significant experience arising from my baptism in the Spirit was the sudden insight of the divine origin of Scripture – suddenly it made sense, after I’d been struggling with reading it for several years.

Normative for others? Of course not – I’m not the Pope. But if one wants to argue for the primacy of the Holy Spirit as revealer, that’s my particular testimony.

The reality of His people having the Spirit doesn’t mean that we will agree at any given moment – only that eventually we will, even if only in eternity. It was a major moment for me when it hit me that for the sub-culture I was raised in, ultimate security was usually found in Biblical inerrancy (and their common interpretations, which they assumed were the only reasonable ones.) Hence the vehement (fearful) defense of it.

The other message was there, too, that our security is in God Himself, but when I realized that the latter was by far the more important, it was something of a revelation for me.

Jon, I don’t think we disagree on substance, but merely on what descriptive words to use. You want to hang on to “literal” and “inerrant” – to me it seems like those words are being stretched to the breaking point (and that they are not themselves Biblical words.) We agree on “inspired” and the fact that, historically, it hasn’t been a trivial task to find out exactly what is the inspired meaning for some passages.

Preston:

I’d agree with you that “inerrancy” is of questionable value these days. I think the reason for it is that the notion has been narrowed so much by certain American Protestants that it has become suffocating even to most other Protestants, let alone Catholics or Orthodox.

I think that Jon has in mind a broader and subtler notion of “inerrancy” than Ken Ham does, so if Jon uses the term, I’m less wary. And maybe in the UK it doesn’t have the suffocating associations it does across the ocean. But for many in North America, “inerrancy” is a fighting word, implying children riding on dinosaurs and a global Flood in historical times that covered the top of Mt. Everest. I don’t see why “inspired” isn’t a strong enough word to do all the necessary work — provided that “inspiration” means something stronger than what happens when a Hollywood screenwriter comes up with a new story for a sitcom.

Sorry for slow response, guys – wife’s birthday, drive to daughter in London – nearly 8 hours at the wheel. Phew.

“Inspired” is fine, but as Eddie says below, it has a low value in general useage, which has been transferred, often, to the Bible. It tends to mean “value added to the text”, or regarding the Bible, that God has “breathed some life into it.” The task then is to find the divine gems amongst the human effort.

But the Scripture word, θεοπνευστος has more the sense of what God breathes out through the human writers: and so Peter speaks of men “carried along by the Spirit” and Hebrews that “God spoke to us through the prophets.”

Charles Hodge speaks of the process of inspiration as being wrongly applied purely to the text – it implies God’s hand in the call, training and experience of the writers, the historical circumstances, as well as the varied means by which the human agents work, from the visionary prophet to the eclectic proverb-collector.

But the emphasis is on what God speaks, and the theological task is to square that with the culture he has used, the differences in numbers or whatever else. “Literally true”, in the sense that the Fundamentalists use it, is a travesty of the doctrine.

Since I don’t often get to quote Bonhoeffer, here’s another one to close:

Hey, Preston!

I jumped into this discussion for your sake. Did you see my reply to you? I tried to put some thought into it. I’m not expecting an answer as long as mine in reply, but it sure would be nice to hear that you recognized I was trying to some extent to defend aspects of your position. (Or, if you don’t think I was defending any of your ideas, it would be nice to hear where I misunderstood what you were trying to say.)

I think some important points have been absent from these discussions on Christ as a human being. It is obvious that even as a child, Christ understood His Father’s business better then the priestly elite (who in those days were also the intellectuals of Israel) – hardly a common trait for a young boy. It must be understood that Christ was the perfect human being – so discussions which try to portray Him as a typical peasant carpenter who stumbled through an apprenticeship are misguided. What is remarkable is Christ did not turn to His Godhead whe faced with human difficuties, but freely accepted Hus humanity, and yet was without sin. This sets the ‘template’ for what we as Christians should try to achieve – to be completely human as God intended us from the beginning.

I guess if we do not fully comprehend these attributes regarding Christ, the Word of God, we may have difficulties comprehending the testament of God’s people as presented in the Bible.

GD:

Even if Christ was a very precocious young lad on theological matters, that does not prove that he knew everything that God knew, or that he thought of himself as YHWH, creator of the universe, rescuer of Israel from Egypt, and giver of the Law.

I don’t know if he was a “typical peasant carpenter” or not. He may have been given a little more education than a typical Galilean Jew of the day — that might explain how he could talk in the synagogues. But he is not represented in the Gospels as having any formal rabbinic training.

The fact that Christ was without sin, and born of the Holy Spirit, must mean that Christ was not a typical man who walked and talked in Judea, and other various places. I suppose as modern and post-moderns, we may equate the degree of “perfection” of a human being with how much knowledge he has accumulated – in a humorous vane, I guess someone with 5 PhDs may be 5 times more perfect that someone with one (and where does that leave all of those without one little ol’ PhD?)

I suggest that a human without sin will still be hungry and needs to eat, will need sleep, and in fact all of the bodily needs common to all of us. I also state that only another person without sin can fully comprehend the attributes of a sinless person. So I for one cannot add much more regarding Christ as a human being because He was the Son of God. I am also certain that if Christ needed knowledge about the Chinese (or evolution, or chemistry, etc.) to fulfil His task of Salvation for the entire human race (and the creation), He would have had such knowledge. Such knowledge is not essential and so we do not need to find it in the Bible – we have the capabilities to find such knowledge ourselves, and that too is from God.

God speaks to us through His people, and His Son – to persuade us to turn to Him for our good. I do not see this persuasion to include the latest science, nor philosophy – these matters will arise during out time, and they do constitute the culture and conditions of the particular time we live in, but are not the essence of Faith.

It may be difficult for us, especially during this scientific epoch, to comprehend the fact that the message from God is totally true and good, and yet it is delivered to us by imperfect people using error prone language (as made very obvious by my many typing errors, just to mention one source of error). When we add the difficulties that are encountered when we speak to another person, we may wonder how we are even able to communicate – in fact we spend many years leaning how to speak and write, and yet we still we make mistakes.

One of the many reasons why so much effort went into establishing Orthodox Christianity is the fact that we are error prone, and the Church realised that we must agree on how to articulate the central tenets and core beliefs of the Christian faith. Anyone who has spent time reading legal documents will understand this. This is not a reflection of Biblical problems, but a realisation that we human being will inevitably think and speak differently and when doing so, we will find areas of disagreement. We are imperfect, God is perfect.

GD:

I agree with many of your observations here.

Yes, if Christ needed knowledge of chemistry etc. in order to carry out his mission, he would have been given it. That is why I think he knew only as much about chemistry as typical Galilean Jew of the day would have known.

I would apply this to the Biblical knowledge of Jesus. When modern scholars like Walton interpret Genesis, they tell us that we must understand the Near Eastern background in which Genesis was written. But no Jew of Jesus’s day, not even the most learned rabbi, knew beans about the Ancient Near Eastern background of 1,000 B.C. (or even 550 B.C., if you take the improbably late date for Genesis 1 put forward by many scholars). Almost all that we know of those cultures and times, including the relevant languages, we have learned only since the 1800s. Jesus would not have been taught a thing about the “Babylonian world view” or the “Egyptian world view” etc. So he would have had to interpret Genesis without the benefit of the scholarly tools that Walton, Enns, etc. bring to the task. His knowledge would then come out of his textual studies, or from direct inspiration by God. Either of these ways is compatible with traditional Jewish thought of the time of Jesus, and I’m not objecting to anyone who asserts that Jesus understood Genesis better than others because he studied deeply and more diligently, or because from time to time God imparted insights to him that God imparted to no one else. Those ways of knowing are compatible with Hebraic thinking, and fit in very well with the notion that Jesus was a real man, not God doing a good job of faking being a man. That was my main point.

Many of the points from Jon cover the subject so I will leave the discussion – I will point out however, that John 8:51-59, and esp verse 58 – should encourage us to consider the mystery and also the fact that God the Father had a particular view of Christ.

I already conceded the existence of some statements in John; however, even in the passage you cite, which makes one of the most radical claims in the Gospels regarding Jesus’s divinity, he still distinguishes himself from God. (But not enough to satisfy his Jewish listeners, as the sequel shows.)

Jon:

Thanks for the Bonhoeffer references.

To respond (whether in agreement or disagreement) to his remarks on Greek thought and the Chalcedonian formula is would take some research time that I don’t have at the moment. I will make a point about his remark on heresy, however:

I agree with him that the notion of heresy is connected with the notion of teaching authority. The problem that American Protestant sectarianism has is that its declarations of heresy come from multiple teaching authorities, none of which acknowledges the legitimacy of the other authorities. The Methodists can thumb their noses at the declarations of the Reformed, the Southern Baptists can ignore the charges of heresy levelled at them by the Lutherans. Where there is no central doctrine held by all, heresy declarations are merely the imposition of the theology of one party upon other parties; and the Protestant principle (certainly in its American form) makes it impossible to set up an arbiter over the conflicting parties. The imposition of any arbiter would violate the freedom of a Christian (so the argument goes) to worship God according to his own conscience, read the Bible according to his own understanding, etc. Thus, American Protestantism has a cultural commitment to theological anarchy.

That’s not been an entirely bad thing from the point of view of intensity of religious belief: more Americans are *actively* Christian than Britons, French, Dutch, Danish, etc. Many of those countries have at least a nominal national Church (Anglican in Britain, Reformed in the Netherlands, etc.) which in principle should set the definitions or orthodox and heretical, yet religious belief is far weaker in those countries, and stronger in the USA where no national theological standard exists.

However, the American situation is certainly a bad one for coherent Christian *thought*. The theological incoherence of TE is one illustration of this. The TEs are paralyzed — as a group — when asked questions about divine action in evolution, because in order to answer them, they would have to speak out of their individual Christian theologies of sovereignty, providence, free will versus determinism, etc. — and those individual theologies (Lutheran, Reformed, Wesleyan, etc.) disagree. (And to make matters worse, the individual TEs are not even always true to their own theological traditions; Falk isn’t “Wesleyan” at all on questions of creation, for example, and the Reformed TEs often sit very loosely to classical Calvinistic ideas about God’s sovereignty and providence. But that’s another subject.)

Thus, there is not and cannot be any coherent TE theology of divine action. So TE as a collectivity can’t articulate itself in a way that fits it into the millennial Christian tradition. All one can get from TE writers is freelance private Christian theologies, based on their own personal instincts of what God would or would not do. And by the very American Protestant principle to which TEs as American evangelicals subscribe, one is free to simply reject their claims of what God would or would not do, based on one’s own private and idiosyncratic sense of God. Venema can say: “I don’t think God would do X,” and Dembski could reply, “Certainly God might do X,” and then ID/TE discussion stalls over that fundamental disagreement, with no theological authority acknowledged by both who could declare which view of God is right. Anarchy reigns in American Protestant theology, and TE does nothing to address that problem; if anything, it only exacerbates it.

Eddie

Interesting to consider that if that situation had applied when core Christian doctrines were being hammered out in the early centuries, there would have been no core Christian doctrines hammered out, and no Christian orthodoxy from which to dissent – just a disparate set of cults.

I see the variations not as individual interpretations of Scripture, which was how many of the denominations started, allowing still a great deal of theological fellowship if not always practical love, but as different interpretations of inspiration.

That’s where the Fathers differed, as quotes from any number of them on the final authority of Scripture would show (some from Athanasius, Augustine and Irenaeus were bracketed with my Bonhoeffer source). Even the last’s appeal to tradition was to do with the preservation of apostolic teaching.

Jon:

I’m not sure I understand what you mean.

Are you saying that in modern Protestant denominationalism, the differences in interpretation are serious and destructive, because they presuppose different notions of inspiration, whereas in the time of the Fathers, the differences were not so destructive, because the Fathers all had the same notion of inspiration, even if they varied in their interpretations of particular passages?

Well Eddie, all was not necessarily rosy in Patristic times – Cyril hiring brown-shirt monks to intimidate the opposition etc – and then, as now, people didn’t wear a T-shirt with “HERETICS RULE” on it. But there was such a thing as catholicity, and any reading of the Fathers shows that “the Holy Scriptures” featured centrally in it. When push comes to shove, the doctrinal positions that made it into creeds and weren’t reversed by the next general council were those that best accorded with biblical doctrine.

That, in my view, answers your observation about the lack of a basis for Catholicity now, especially in the US. Extolling private interpretation, in itself, weakens any sense of accountability to the Church Militant, Penitent and Triumphant: can you imagine any US academic nowadays submitting to the decision of a general council of bishops and scholars without crying “Foul! Academic Freedom!!”?

But more importantly, interpretations cannot agree if one says, “This saying of Jesus clearly disagrees with my position, but that’s because it’s not an authentic saying of Jesus,” and another says, “I disagree – Jesus did say it, but it’s not binding because it was the human,/i>, culturally limited Jesus who said it,” while a third says, “You’re both wrong – God is still revealing new truth through the social advances of democratic society, and so the Spirit brings about the evolution of the faith principally through unbelievers.”

Meanwhile, outside, feminists with banners are objecting that to take the Bible, or any other text, as authoritative is intrinsically oppressive of minorities.

Good cartoon.

http://wp.production.patheos.com/blogs/peterenns/files/2015/02/11007614_628927553920047_152492327_n.jpg

“Interesting to consider that if that situation had applied when core Christian doctrines were being hammered out in the early centuries, there would have been no core Christian doctrines hammered out, and no Christian orthodoxy from which to dissent – just a disparate set of cults.”

This sort of assumes that Jesus isn’t capable of running His church. The impending chaos of the early days resulted in an understandable appeal to an apostolic succession and bishops and ultimately a magisterium. But I can’t see anything to convince me of the infallibility of The Magisterium or any of the little magisteriums that have followed.

They are necessary in the way the rest of institutions are necessary for human beings in groups to do anything, but when one decides that it is infallible, nothing good results. The history is that the authorities have needed reforming many times, and more often than not, it’s someone on the fringe who starts the reform, which shouldn’t be surprising when the church’s founder started on the fringe Himself, and, before His death, never left it.

We humans reflexively look for an authority that can serve as an anchor, but all the available authorities in this world are either human or depend on fallible human interpretation.

In the last 2000 years the church has tried episcopacy and the accompanying magisteria, and inerrancy plus multiple magisteria to do Biblical interpretation. (Lip service is given to every man and his Bible, but most people are drawn to groups and leaders.) Neither has proved to be remotely close to flawless, but nonetheless the gospel is intact and God has His people. People are always looking for the true temporal spiritual authority, and Jesus is always there saying, “I am the only one who is up to that job.” Jesus has been running his church all along, even if it has run amuck a bit at times. He will continue to do so.

A number of valid and important points are made by png. I would add one or two if I may. Orthodoxy, which inevitably made statements that rested on apostolic authority, was not the result of institutionalisation. Much of the history of that time (after Rome stopped killing Christians and decided to adopt Christianity as the Sate religion) reflected in many ways, the politics that emanated from the Emperor and his central power base. It is this turmoil, which was due to various players trying to manoeuvre themselves into power via political alliances, favour with the emperor, and by creating a large following, that had a lot to do with the Church developing the Orthodox Christianity that has lasted to this day – it needed to be that robust. During these days, there was one Church, and as I mentioned, authority was always related to Apostolic teachings, because Christ commissioned the Apostles for such a task. So far from assuming Christ did not run His Church, the facts show that is how Christ ruled His Church.

Historically I agree with the view the institution that adopted the name of Christ often showed, by its behaviour and conduct, that it was run by non-Christian – but such events did not destroy the Church Christ established, and one very good reason for this, was due to the labours that culminated in the protection of Scripture (the bible) and the accompanying orthodox teachings. I find it an extraordinary aspect of the history of Christianity, that it seems to have suffered more (from evil acts and a desire for wealth and earthly power by those who insinuated themselves into the institution) since it became an arm of the state, then the days when it faced persecution by the state. Perhaps the enemy within (who is harder to identify) is more deadly than the enemy outside who declares himself.

Prreston

In my view you’re excessively dichotomising the person of Jesus from appointed means. It’s certainly true that the Church is Jesus’s project, as Acts makes clear (being about what Jesus did and taught next – but Acts also shows that his leadership was by no means simply invisible and providential, still less mediated only through personal mystical encounter.

Humanly speaking, since Jesus came in the flesh into human history, the appropriate way for that essential story to lead to faith was by being testified by witnesses. And so it was that in Acts 4.23ff the Church, which assesses its situtation through application of the OT Scriptures, prays and is granted an outpouring of the Spirit – in order to proclaim God’s word boldly. And as Paul says in Romans, “How can they hear without someone preaching to them? And how can they preach unless they are sent?” (adding then yet another Scripture quote).

Jesus, of course, had already appointed apostles to lead his Church, and we find that they in turn appoint elders in every town, and that Paul as he nears death urges Timothy to preserve sound teaching (with the help of the Spirit) and entrust it to reliable teachers in turn. An infallible magisterium it is not, but Christ instituting a human/spiritual leadership to maintain the Church it certainly is.