The placebo effect always interested me when I was in medical practice. After all, it’s the only treatment that works across the entire spectrum of illness and the standard against which all other drug effects are judged. I caught the repeat of a BBC documentary on it here (unfortunately UK readers will only be able to catch it for a couple of weeks and those in foreign parts not at all. Sorry).

I’m not so much interested here in trying to explain the effect, which is far from straightforward, but in using that lack of straightforwardness to discuss what it may tell us about the nature of being a human being, or in other words, how we have been created.

What the documentary shows is a series of pieces of research in which placebo effect was found to alter not only the perception of disease or stress, but the actual mechanisms involved. For example, giving placebo oxygen to people at high altitude actually alters the levels of a neurotransmitter that, usually, responds to lack of oxygen by mediating muscle pains and so on. Though pO2 remains low, the transmitter maintains its levels as though it were normal, and the patient’s exercise tolerance is like that of someone on oxygen.

The other most notable example in the film was a trial of placebo in established Parkinson’s disease sufferers, which I guess most people know is characterised by dopamine depletion in the basal ganglia of the brain. The main interviewee was one who was given placebo, after a washout period for his regular bromocryptine treatment, and showed a response at least as good as he would have done to the drug. Scans on the placebo group showed there was actually an increase in dopamine levels when they were (falsely) told they were in the drug group, accentuated when the placebo was actually administered.

Now bromocryptine is a dopamine agonist (ie stimulator), so the film commentary was suggesting that the placebo effect works via the body’s chemical receptors in the same way as the drugs do. But that’s really a non-explanation on reflection. The basis of, say, bromocryptine’s therapeutic effect is that, by the simple laws of chemistry, a deterministic effect on a specific part of the body is produced (subject to provisos about varying physiology, secondary effects etc), just as certainly as iron will be sulphated by sulphuric acid. The underlying principle is that the body is a system of separate chemical reactions, which can be modified, to some extent, piecemeal. Bromocryptine is a magic bullet directed to its target by the laws of nature.

What was happening in the Parkinson’s case, it seems, is that a (presumably) deficient natural dopamine agonist was made available in large quantities by the placebo effect in the absence of the expected artificial agonist, bromocryptine. If anything, one would expect natural factors to be chronically suppressed in those under such drug treatment (that’s the supposed basis of substance addiction, after all). What pathways, then, led to such a powerful effect?

Naturally enough the programme dealt with the role of belief in the placebo effect, from the success of subterfuge in pre-modern medicine, through the effects of hypnosis and – probably most significantly from my point of view – to the relationship between doctor and patient. In doing so, though, the obvious factor of “faith” received something of a hit. For a couple of pieces of work were described in which the effect of telling the patient they were going to receive placebo was assessed. One woman, being treated for irritable bowel syndrome, had just completed a vocational health course, and so was actually very skeptical at the thought of being given fake pills. But she decided it was not going to do any harm – and benefited from a powerful placebo effect that only ceased when the pills ran out (owing to the ethical design of the trial). Something odd is happening here.

Naturally enough the programme dealt with the role of belief in the placebo effect, from the success of subterfuge in pre-modern medicine, through the effects of hypnosis and – probably most significantly from my point of view – to the relationship between doctor and patient. In doing so, though, the obvious factor of “faith” received something of a hit. For a couple of pieces of work were described in which the effect of telling the patient they were going to receive placebo was assessed. One woman, being treated for irritable bowel syndrome, had just completed a vocational health course, and so was actually very skeptical at the thought of being given fake pills. But she decided it was not going to do any harm – and benefited from a powerful placebo effect that only ceased when the pills ran out (owing to the ethical design of the trial). Something odd is happening here.

For the sake of argument, let us suppose that simple belief is the key factor in the placebo effect. What, then, is presumably a higher and “global” cerebral function (some would even say an illusion) – a general belief that a pill will make a particular problem better – is able to exercise intelligent and targeted control of diverse physiological functions which the mind normally does not control, and of whose details it is actually entirely ignorant. A vague belief becomes a magic bullet. It’s the equivalent of a chemist being able to produce an anomalous result simply by expecting the wrong outcome from a reaction. Now that is magical.

At the very least, this demolishes the scientistic belief (!) that science affects reality in a way that faith doesn’t. It actually affects it, in the placebo effect, in exactly the same manner that allopathic drugs do, and you can measure it instrumentally. In fact, one has to ask what role these effects play in the normal therapeutic situation. Does bromocryptine, for example, in practice work purely on cell chemistry, or by mediating the complex and opaque mechanisms of belief? Or both?

In one sense that’s not a matter of doubt, as the documentary went on to show how directly the personal therapeutic relationship between doctor and patient influences outcomes of identical interventions. I can say that I fought some of my peers on that score over the years, being convinced not only that it was the right thing to do to be personally interested in my patients as people, but that it positively affected outcomes. But scientism is strong ju-ju, even in the modern medical profession, and all the pressure was towards making sure a trained and competent practitioner was available to follow best practice, even if that meant interfacing with a computer. What really counts are the controlled trials. But it isn’t so.

Yet it actually seems to be that emphasis on relationship rather than simply belief that is at the heart of the placebo effect. It doesn’t explain how a patient’s attitude “tells” the body what adjustments to make to its detailed physiological processes and chemical pathways, but by telling us where to look, it weakens the whole model of man as a mass of interacting material mechanisms. For me to be able to mimic the effect of a drug at the molecular level simply by taking thought suggests that a more global principle governs my existence as an individual human: something like Aristotelian form and the concept of a true “substance” fits the data better than that of individual genes or other molecules rubbing shoulders as they struggle to benefit themselves. My physiology is actually accountable to the indivisible whole – of which my mind is a controlling part.

Yet it actually seems to be that emphasis on relationship rather than simply belief that is at the heart of the placebo effect. It doesn’t explain how a patient’s attitude “tells” the body what adjustments to make to its detailed physiological processes and chemical pathways, but by telling us where to look, it weakens the whole model of man as a mass of interacting material mechanisms. For me to be able to mimic the effect of a drug at the molecular level simply by taking thought suggests that a more global principle governs my existence as an individual human: something like Aristotelian form and the concept of a true “substance” fits the data better than that of individual genes or other molecules rubbing shoulders as they struggle to benefit themselves. My physiology is actually accountable to the indivisible whole – of which my mind is a controlling part.

The influence of the therapist’s mind on that unity speaks also, I think, of the fundamental reality of our existence as social beings rather than isolated individuals: as a doctor, there’s some sense in which my mind, with its own beliefs and knowledge, acts symbiotically with that of the patient, for their good.

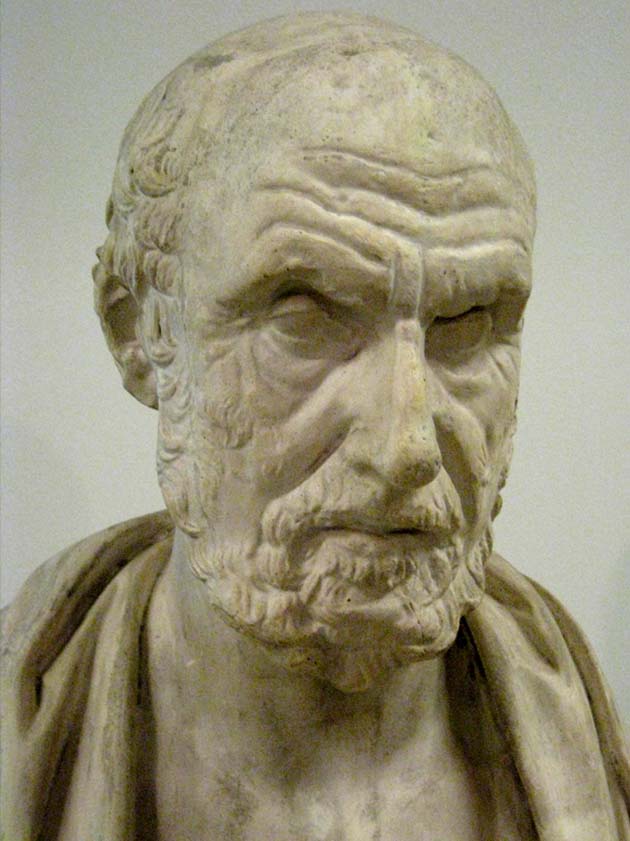

If there’s any truth in that, quite probably the opposite is true as well. A poor or non-existent clinical relationship would be expected to negate the placebo effect – but it might even reverse it. The drug trials always test against placebo, but not against the less quantifiable effects of human relationships. The doctor is, to a large extent, the treatment. As one GP wrote, in the now unfashionable spirit of Hippocrates:

Facts can be learned by anyone; experience is earned through years of practice; wisdom is granted to us only if our hearts and minds are open, in our practice of medicine, and in our lives.

Indeed, as a final thought one has to ask whether the placebo effect may not have most to say about the way that disease arises in the first place, for if my relationship with a doctor can turn receptors on, one would expect other relationships to be capable of turning them off. I’ll let Hippocrates have the last word:

Life is short, and Art long; the crisis fleeting; experience perilous, and decision difficult. The physician must not only be prepared to do what is right himself, but also to make the patient, the attendants, and the externals cooperate.

So has any sort of “anti-placebo effect” ever been studied? I.e. If a positive relationship or expectation can effect positive outcomes in the absence of the real drug …. Can a negative relationship or expectation nullify the gain given by the presence of the real drug?

I suppose the simple answer is, of course, yes; since that is part of the conclusion of the placebo effect in the first place: that a demonstratedly good placebo effect must imply the inverse as well in this particular case. Still … do hypochondriacs shoot themselves in the foot?

Merv –

Your first paragraph is a set of interesting questions, in that because the placebo effect is use as a control in most cases, nobody thinks of it thereafter. But there’s a common finding that drug trials, when repeated after a few years, tend to give worse results. You may have seen press releases about last decade’s wonder anti-depressant being shown now to be no better than placebo. But not many people ask why it was much better than placebo in 2000.

Maybe the answer is investigator bias (despite double blind and the rest of it). Maybe somnething more exotic is happening (but don’t ask me what).

Do hypochondriacs shoot themselves in the foot? Anecdotally yes, of course. I became very aware over the years that my own susceptibility to bugs amongst the patients related directly to my overall state of mind.

But I remember a study I read in my chronic pain treating days that sufferers from fibromyalgia (often associated with various mental issues and widely believed to arise from stress, personality etc) have been shown to process pain in the CNS quite differently for others. Relating to a a recent blog topic (!), some studies suggest that types of sexual activity can affect brain structures, thus confusing the chicken and egg question of what causes what.

It all cries out for study, but being such a different biological model from that employed by the pharmaceutical reserachers and universities it may take a long time to happen.

I suppose the placebo group and the non-placebo group, could each be subdivided again. You could have the Placebo sub-group (that knows its a placebo), Placebo (but think the meds are real), Non-Placebo (and informed as much), Non-Placebo (but lied to, and told that they were getting a placebo.)

Then the last group would be the group of interest to answer my “anti-placebo” question. And if all this was done in a double-blind sense (so doctors don’t even know if they’re lying or telling the truth), things would get really complicated. I can understand why these studies are cost-prohibitive to scale up.

There would also be the deflation of trust. With all this lying going on, anybody at all associated with a study would probably deprecate what they’re told concerning meds, since they would know that whatever they are told must necessarily correspond with experiment parameters rather than with truth.

P.s. I know of someone (a child at the time) who asked for aspirin for his headaches often enough that his parents sometimes offered him a placebo instead. He did not yet know what that meant, and assuming it was a brand name would sometimes request that since it worked well. He’s probably figured it out by now (but it should still work if he’s willing to continue that practice, based on what you say above!)

P.P.s. Imagine the confusion if a company started marketing a real drug under the name ‘Placebo’. It would be a way to play with researcher’s minds. Buyers would be understandably cranky if it was at all expensive!

Merv

The question of trust is an important one, which is why the studies that showed placebo working when patients were fully informed are so interesting, and also those showing that therapeutic relationship may matter more than belief.

In my own practice, I fumbled to the idea that the aim was to make the best use of what I honestly believed did work, which meant I would seldom if ever advise anything purely as a placebo. Maintaining a good relationship, and talking confidently about the treatment I was giving because I believed it was effective was both honest and likely to maximise efficacy.

I love the idea of the drug named “Placebo”. You could have a whole genre of ironic, anti-placebo drugs, like an antibiotic called “Resistan” or an antiarthritic called “Krekon”. Some of the early antidepressants seem to have been named on a similar principle – one was called “Oblivon” which sounds like something for capital punishment rather than mood-improvement.