I’ve written before that miracles are not the most important theological issue I have with methodological naturalism: special providence is, because Scripture describes it as all-pervasive in the affairs of both man and the natural world. God is constantly active, according to the Bible, in managing his household, including by the answering of prayers, and I remain unconvinced that we can properly understand the physical world without somehow accommodating that truth. But nevertheless I want today to consider specifically miracles of healing rather than daily providence, because I’ve been reading about them recently.

Craig Keener’s magisterial two-volume treatment of miracles in part (amongst several other aims) sets out to show the fallacy of David Hume’s claim that miracles claims are extraordinarily rare, and therefore suspect in that respect alone. Keener collects a vast collection of case histories, some extremely well-documented, some less so; and certainly in some cases raising as many awkward questions about the nature of miraculous activity as simply supporting supernaturalism. Hume was just wrong (because he took his limited experience as an Enlightenment skeptic as normative) – miracles are a common human experience (though to what extent they are truly supernatural is another question that is orthogonal to Hume’s claim that they are rarely encountered).

It strikes me that such a widespread phenomenon does pose more of a challenge to Christians disposed towards what Reijer Hooykaas called “semi-deism” than is realised. Many Christians, especially in the sciences, are happy to accept that God did some miracles in biblical times, and might conceiveably do so now – but exceedingly rarely, if at all; for nature normally operates in a law-like way, and the existence of many miracles would disrupt that. That’s exactly the same case that theological cessationists make – and probably the ultimate source is the same Enlightenment rationalism. Keener’s evidence suggests that they are, in fact, not uncommon at all, making them a significant element in our mundane reality rather than an anomaly one can ignore.

I can confirm this from my career in family medicine, working in a Christian practice, during which I was also for a number of years in church leadership. Offhand I can remember half a dozen healings that impressed me either because I knew the patients well, or because I was involved myself. So not a big number (there were probably more claims I have forgotten), but a smattering of interesting phenomena.

The couple of cases (in church, not work) in which I was involved in prayer included a young mother having great difficulty getting around with a young baby at a Christian conference because of an acute back injury. A group of us prayed for her, and she immediately reported she had no more pain. Small beer in the miracle stakes, I guess – but providential for her.

The second instance was a teacher who asked after church if I would pray for the bad wrist she’d had for a few weeks. Before I gathered a couple of other members to pray, clinical habit led me to examine her. She appeared to me to have tenosynovitis (and I wasn’t a bad diagnostician in those days), a condition which, in the surgery, I’d normally slap into a splint in extension, inject with steroids, and add dire warnings to rest it because, in a good proportion of cases, it tended to become chronic and had even lost people their livelihoods. Even when my treatment worked, it was usually rather slow to settle. I didn’t say any of that, but it more or less removed any faith I had in the prayer I would offer. I should add that she was a lovely but toughminded believer – I’m pretty sure she felt she ought to ask for prayer, rather than expecting much from it.

The following week I intercepted her after the service and asked after her wrist. She admitted that her expectations had been low, but said that to her surprise her wrist had felt hot as we prayed, and she’d had no pain since. I rather expected her to turn up in a splint at some later stage, I confess, but she never had a recurrence.

The most amusing case in my medical practice was a rather overweight Christian lady who, for a number of weeks back in about 1983, called us out regularly at night for bouts of severe upper abdominal pain that really didn’t respond to any analgesics. Mystified, I read through her notes one evening and speculated that this might be some kind of psychogenic pain somehow linked to her guilt about being obese. Move over, Freud. But meanwhile my colleague admitted her to hospital one troubled night, where pancreatitis was diagnosed. So much for psychosomatic pain. She was discharged with follow-up the next day, but never had the pain again.

A few months later I included her case (anonymously) in an article I did for The Physician on “psychogenic pain”, basically arguing that I should have worked harder to find the physical diagnosis before jumping to imaginative psychological conclusions, but suggesting that the rather dramatic resolution may have been partly related to her relief at discovering the true cause, since the hospital treatment was actually minimal. A professional colleague’s letter on the correspondence page poo-pooed my assessment and said that, without doubt, when some stress next arose her psychogenic pain would return. But it never did, and she died of something completely different after I retired.

But here’s the amusing part – it was only maybe twenty years later, when I mentioned to her that I’d used her story in a journal article, that she told me what she’d not told me before – that a group from her church had come to the hospital after her admission and prayed for the healing of her pancreatitis. That article would have been a lot less welcome in The Physician, I suspect.

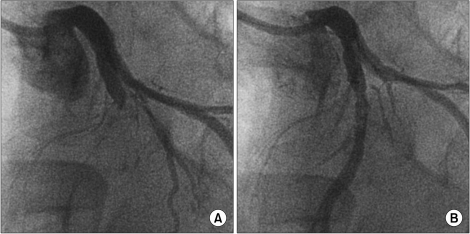

The best case happened to a patient who was also a Christian friend of mine. He was getting increasingly troubling angina pectoris, had coronary occlusion confirmed by angiography, and was on all the pills whilst awaiting bypass surgery. This chap was of a somewhat Charismatic bent, and so I wasn’t surprised when he told me that he’d had laying on of hands at a prayer meeting, and felt sure that he had been healed.

Charismatic he may have been, but he was also a good patient who trusted my spiritual and medical judgment, so despite the fact that he appeared now to be symptom free for the first time in months, I kept his medication going pending a repeat angiogram, which I requested from the friendly specialist in a full explantory letter. Though the consultant was not a Christian, he kindly complied, and was very surprised when the angiogram came back as clear. We gradually tailed off his medication, and maybe fifteen years later he’s still well, according to the Christmas cards he sends.

But here’s the point I want to raise from his case. My profession is trained in a scientific discipline, and therefore under the assumptions of methodological naturalism. However, unlike, say, population geneticists, the luxury of knowing that no non-natural possibilities will encroach on your field isn’t shared by doctors.

This actually makes a difference even in daily practice, quite apart from miracles. It took a series of minor illnesses at a time of personal unhappiness to make me realise that the germ theory of disease I’d been taught for six years completely ignored perhaps the main factor in who will catch most common infections – their mental state. Once I realised that, it explained why I could work close to patients through every new flu epidemic without vaccination and without succumbing – except when there were other pressures on my life, when I was quite likely to find myself off sick with all the symptoms.

Likewise, for my entire medical career the placebo effect was merely something against which to test expensive new drugs: because it appeared to be a case of immaterial mind over matter, it simply didn’t register as a reality to be investigated or utilised under methodological naturalism. I had to learn for myself how to instill personal confidence, and even had to argue with well-schooled colleagues that it mattered.

For these reasons, and others (including the fact that I was seldom engaged in research) I sat somewhat loose to the principles of methodological naturalism: healing a human person is to do with much beyond the merely material, which is why the grass-roots doctor clings to that concept of the “healing arts” as well as “evidence -based medicine”. So in those occasional cases where God seemed to have done the unexpected, I was happy to just shrug, make sure nobody was being gulled, and give thanks.

But now put yourself in the position of the hospital specialist in charge of my friend’s case: he is a cardiologist, and as Maureen Lipman’s character said, “You get an ‘ology’, you’re a scientist!” – this is only a short clip, and it’s funny:

Now, in your case, we’ll say you’re a Christian cardiologist, so you fully support, and even insist on, methodological naturalism in your science, whilst being quite happy to be a “metaphysical supernaturalist” as a human being. It would be interesting to know how you might reply to my new letter once the clear angiogram arrived on your desk, but here’s a harder question.

Some months later, you get a letter from a medical researcher at Oxford University who is doing a study on claimed faith-healings. He has been informed of the case by the patient, and has obtained the necessary permissions for information from him and the GP. He requests a report of the relevant records, and especially documentation of the “before and after” angiograms, together with your own professional opinion of the merits of the case (he points out that previous studies have lacked academic credibilty because of a lack of suitably qualified medical input).

Now, what would your response be (I’d be interested to hear – let’s make it a challenge like Joshua Swamidass’s “miraculous tree” fable)? Possible responses might include:

- Replying that, according to methodological naturalism, research on possible miracles is an unsuitable subject for science, and that you will not co-operate.

- Replying that, although you are willing to share hospital records, as a scientist you will refrain from giving any opinion on what is a non-scientific matter (even though you are being asked to comment on the significance of purely material evidence).

- Replying that, speaking as a cardiologist, you are of the opinion that anomalous spontaneous resolution of occluding plaque is the proper explanation (leaving your identity as a Christian at the office door).

- As above, but with a footnote that as a Christian rather than a scientist, on Sundays you actually believe the resolution was not spontaneous but divinely mediated as a result of healing prayer… even though your belief is entirely based on scientific medical investigation of material evidence.

- Or some other response (Keener reports, for example, a number of occasions in which doctors were happy to risk a malpractice suit by saying the original diagnosis of multiple doctors was wrong, rather than admit to a healing!).

The issue is a real one. A leading doctor in Britain’s Christian Medical Fellowship, Peter May, wrote a book debunking a sympathetic investigation of healing miracles by another doctor, Rex Gardner. Craig Keener points out a quite surprising anti-supernaturalist bias in May’s book, such as preferring unlikely and unsupported naturalistic explanations to the testimony of doctors actually involved in the cases. (Incidentally, I was introduced to Dr May once, at a meeting in London of Christian leaders, addressed by Phillip Johnson: May had previously surprised me by being the first Christian I’d encountered who railed against the whole principle of Intelligent Design in the CMF journal: could his stances on ID and on miraculous healing somehow be linked to methodological naturalism somehow encroaching on his Christian metaphysics?)

My point is this: if the supernatural is not something that happened long ago, safely far away and exceedingly rarely, but something that drops a brick into the middle of your own work – in this case hard data and a case history strongly indicative of non-natural agency by the very God you worship and proclaim as Lord, then how far should methodological naturalism constrain what you are willing to discuss, or confess openly, beyond the constraints of methodology in your scientific understanding of the world?

Jon

You might have noticed that Merv, and then I, in our comments at Biologos new Swamidass thread have given you the blame for instilling some new ways of thinking in our worldviews. I call it a “corrupting” influence. I hope you are properly contrite.

And now here you are doing it again. Well, sort of. I should admit that I have for a very long time had my own such subversive thoughts. In fact, long before I became a theist, I was intrigued by the placebo effect, and thought it would make a fine research subject (for someone else, that is).

Of course we know that medicine is part science, and part art, and very large part evidence of mind body interaction in still mysterious ways. But when you say that for the non medical scientist “the luxury of knowing that no non-natural possibilities will encroach on your field” I, as a former lab researcher, and an occasional population geneticist to boot, am not quite positive that you are right. Population genetics is of course quite mathematical, and math is something that requires a very advanced level before any surprises appear. But that is all about the models, not the reality in the field (as Argon eloquently stated on that same Biologos thread). When one actually looks at the reality of the genetics of populations, things are not so tidy. In fact things are notoriously not tidy in practically any field of experimental, material naturalistic based science.

I remember once giving a presentation in front of some lawyers to explain my testimony on the effects of some chemical. I showed a graph with a very strong correlation between the chemical concentration and the effect, including the linear correlation line (R = 0.9) with all points close to the line. An impressive result. But one of the lawyers (poor ignorant fellow) asked “But why dont all the points fit directly on the line?” I laughed and shook my head, and the opposing expert did the same, and we exchanged a glance. How sad that non scientists have no idea of all the sources of error that can affect actual data. I believe I replied to the effect that if all the points had fallen on the line, that would be pretty strong evidence of fraud.

Only decades later, did I start to wonder why that is true. Its not that some things dont fit as they should. NOTHING fits as it should. Yes, I am sure this is almost entirely due to random variations, equipment issues, the problem with getting experimental conditions just right and so on. We dont investigate these sources of “error”, there are too many, and it isnt profitable to waste time on them. We have p values, and statistical ways to rule out chance, and be content with a really really good fit. Or even an indication that the data fits this model better than any other model, so this model is right.

I know this is quite far from a patient recovery that cannot be explained by MN. But who knows, maybe we have been staring at that thing beyond MN for more than a century in our data tables, and simply not seeing it.

Of course the above is heresy, but Im retired, so let it be.

Thanks for this excellent thought, Sy. Of course, I repent in dust and ashes for thought-crime and perversion of innocents, just to get that out of the way…

Of course, as you mention it I’m even aware in my own very limited experimental scientific experience that data must always be massaged to fit the graph. It was so in simple school physics (hence my remark about “one point and the origin” to Argon at BL!), more so in chemistry, and of course exponentially more still once one started doing experimental physiology and so on at University. Get to sociology and medicine and you’re looking not for clear cause and effect, but a faint signal amidst the noise of reality.

My training being in social psychology and medicine, it’s very easy to forget there’s much “natural” to be methodical about.

The variability in experimental data naturally has any number of natural explanations, as you say (though I wonder what those “random variations” actually mean? Random physical laws?).

But popular science, and even science’s common self-assessment, thrives on the idea that tightly excluding variables from experimental design leads to precise observations and mathematical laws that represent the underlying truth. In fact (if I interpret your extensive experience aright) it just leads to a degree of tractability in the confusion of life – it sorts out, to a degree, the regularities from everything else.

But maybe the idea that there is no room in which divine action could occur – and even to be observed in the deviations from precision – is in fact the same kind of blanket assumption that led a century of biologists to know that the fossil record confirms Darwinian gradualism, when S J Gould blew the gaff on the fact that it does no such thing.

And now I must go and feed the fairies at the bottom of my garden…

Hey Jon,

The question is how to think of miraculous healings in today’s world light of MN. Good question. I give multiple answers.

As a scientist, I would would look for a natural cause for the healing. I would want to find it and understand it so I could help other patients. Sadly, because this healing is not reproducible, and we observe spontaneous regression (because medicine is messy) all the time, one patient is not enough to figure out anything with confidence. So this just becomes the exception to the rule we cannot figure out. No scientific proof in case studies here.

As physician, I am not constrained by MN in practice (because medicine is not science), but I am constrained by standard of care and patient consent. Therefore, I do not alter the patient’s care at all. If they requested, I would pray for them in faithful expectation of God’s healing. I would also thank God with the patient if healing came.

As a Christian, I would pray expecting that God might heal. Or not. But I have faith that He could if He so chose. And He desires my request.

As a theist, I know that God intervenes in this world, but only through eyes of faith can I see this. Science? She is blind.

Hi Joshua

Thanks for commenting (with your physician’s hat on). I was, of course, interested in the interface of clinical medicine with science (and hence the proposed scenario of a how a cardiologist would respond to a response from a clinical researcher for information and opinion).

Proof isn’t the issue, necessarily (or even conceivably, if we concede that science doesn’t do “proof” any more than it does “miracle”): we’ll assume the researcher is just seeking to gather evidence to see if there’s a pattern that might increase knowledge, just as someone might in investigating the placebo effect – only in this case, the reported cause is divine interaction. Does the distinction exclude the latter from such investigation? Or perhaps one might refuse to co-operate on the basis that divine action is not amenable to such research – though that would be to place a value judgement on another’s investigation.

I’m interested (not at all surprised) that you might pray with patients. But in this country that’s been deeemed by the profession to be off-limits, even with patient request (which is considered to be potentially exploitative… vulnerable patient pressured by powerful authority figure to agree to irrational faith-healing, etc). One could get suspended or struck off for using non-naturalist methodology – one reason much more of my experience of healing prayer was in a church rather than a professional setting. Though in truth I never felt the profession had a greater call to my obedience than the Lord.

On your last point, I think our viewpoints differ – I think the action of secondary causes to produce effects is just as much a matter of faith as divine action. Science has made choice to assume cause and effect is valid and, in practical terms, autonomous (bypassing Hume’s arguments thereon), and that our perception of such causes and effects is a reliable reflection of reality. It also, in practice, assumes a closed causal nexus, so that it is assumed that any intervention, or rather ongoing activity, by God would not be outside this nexus (or else it could be observed directly, without assuming some bizarre “natural” cause is to be the preferred hypothesis).

It seems that metaphysics is still the key criterion, more than methodology.

Here’s a relevant quote from Craig Keener (writer of the 2 volume book on Miracles) on methodological naturalism. After a discussion of the legitimate use of MN in constraining the sphere of inquiry, he adds:

He’s undoubtedly hit the nail on the head.