Back in March I did a piece arguing against the univocity of God’s being and ours (as the root of many current theological evils), and used the metaphor of those authors who have appeared as characters in their own fiction, but can never truly be seen as occupying the same world as their creations. It’s a useful analogy, I think.

Back in March I did a piece arguing against the univocity of God’s being and ours (as the root of many current theological evils), and used the metaphor of those authors who have appeared as characters in their own fiction, but can never truly be seen as occupying the same world as their creations. It’s a useful analogy, I think.

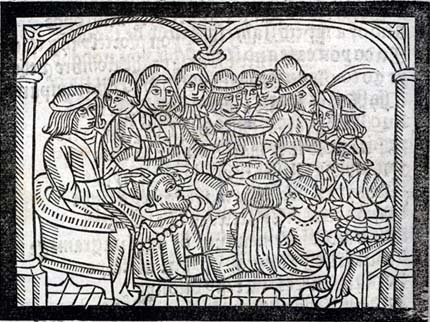

I was reminded of it again last weekend when, waiting around for news of our daughter’s new baby (It’s a girl! It’s a girl!), I was re-reading G K Chesterton’s excellent introduction to Geoffrey Chaucer. Chesterton writes how Chaucer, in Canterbury Tales, is another of that select band of authors who appear in their own work, only he does it with far more wit and subtle meaning than most.

For those unfamiliar with the poem, you should read it, after Chesterton perhaps – we may be one of the last generation of English speakers able to get the gist of its wonderful fourteenth century language without “going on a course.” Chaucer introduces his poem (and his lilting versical metre) with a description of how the sweet showers of spring awaken the desire of people to make pilgrimage to Canterbury:

That rhythm continues through the prologue and the tales that the various characters tell to enliven their journey, until in the pub one evening the host, Harry Bailly, picks on Chaucer himself (trying to look invisible in a corner) to tell his tale. Chaucer says he only knows one rhyme, and the host says that from the look of him it should be a good one. But instead, Chaucer launches into some dreadful doggerel about a knight’s deeds of derring-do in an utterly banal rhythm:

That rhythm continues through the prologue and the tales that the various characters tell to enliven their journey, until in the pub one evening the host, Harry Bailly, picks on Chaucer himself (trying to look invisible in a corner) to tell his tale. Chaucer says he only knows one rhyme, and the host says that from the look of him it should be a good one. But instead, Chaucer launches into some dreadful doggerel about a knight’s deeds of derring-do in an utterly banal rhythm:

Listeth, lordes, in good entent,

And I wol telle verrayment

Of myrthe and of solas,

Al of a knyght was fair and gent

In bataille and in tourneyment,

His name was Sir Thopas.

This goes on for several pages before the host actually shouts it down as rubbish:

“Namoore of this, for Goddes dignitee,”

Quod oure Hooste, “for thou makest me

So wery of thy verray lewednesse,

That also wisly God my soule blesse,

Min eres aken of thy drasty speche.

Now swich a rym the devel I biteche!

This may wel be rym dogerel,” quod he.

Chaucer protests at this unfair treatment:

“Why so?” quod I, “why wiltow lette me

Moore of my tale than another man

Syn that it is the beste tale I kan?”

“By God,” quod he, “for pleynly at a word

Thy drasty rymyng is nat worth a toord,

Thou doost noght elles but despendest tyme.

Sir, at o word thou shalt no lenger ryme.

Lat se wher thou kanst tellen aught in geeste,

Or telle in prose somwhat, at the leeste,

In which ther be som murthe or som doctryne.”

Now Chesterton complains that the critics of his day, entirely missing the joke, tend to focus on Sir Topas as a parody of some rather bad poetry of Chaucer’s time. But clearly the joke is that the only person amongst the pilgrims who can’t do poetry is the poet. Chesterton emphasises that it’s even more than that – this incompetent rhymer is, in reality, the person who has written not only the poetry in the book, but created the entire world of Canterbury Tales, including the critical host who shuts Chaucer up. The host is quite unaware that he’s only able to speak habitually in flowing iambic pentameter because Chaucer created him thus!

Now Chesterton complains that the critics of his day, entirely missing the joke, tend to focus on Sir Topas as a parody of some rather bad poetry of Chaucer’s time. But clearly the joke is that the only person amongst the pilgrims who can’t do poetry is the poet. Chesterton emphasises that it’s even more than that – this incompetent rhymer is, in reality, the person who has written not only the poetry in the book, but created the entire world of Canterbury Tales, including the critical host who shuts Chaucer up. The host is quite unaware that he’s only able to speak habitually in flowing iambic pentameter because Chaucer created him thus!

Now to the mediaeval mind – in many ways so much more intellectually sophisticated, actually, than our own – there was a serious disclosure of self-knowledge in this literary joke. Chaucer was, Chesterton suggests, pointing out the shadowy and unworthy nature of even our best works. The poet may make a world that seems brilliant, but in comparison to the work of the real Creator, God, all his “drasty rhyming is not worth a turd.”

In this context, the fact that the host goes on to demand a joke, or something “with educational value” in prose is significant. He gets it in the form of the worthy tale of Melibeus, whose prudent wife Prudence keeps him from rash revenge. To our ears it’s boring and moralistic, but the host takes it as a worthwhile lesson (if directed as much at his wife as himself):

Oure Hooste seyde, “As I am feithful man,

And by that precious corpus Madrian,

I hadde levere than a barel ale

That Goodelief my wyf hadde herd this tale!

For she nys nothyng of swich pacience

As was this Melibeus wyf Prudence.

By Goddes bones, whan I bete my knaves

She bryngeth me forth the grete clobbed staves,

And crieth, `Slee the dogges, everichoon,

And brek hem, bothe bak and every boon.’

So in fact, the poet steps out of his art to deliver something of more practical value than all the tales that have made Chaucer justly famous (yet it’s telling that some modern editions miss out, or summarise, the Tale of Melibee, thinking it more burdensome to readers than the dreadful Sir Topas). Chaucer ends his moral story with his hero forgiving his enemies because he knows his own faults:

“For doutelees, if we be sory and repentant of the synnes and giltes which we han trespassed in the sighte of oure lord God, he is so free and so merciable that he wole foryeven us oure giltes, and bryngen us to the blisse that nevere hath ende.” Amen.

Chaucer is here affirming, I think, that the man who is on the surface an urbane and witty poet is, at the deepest level, a sinner in need of God’s forgiveness. Chesterton ends (where I will carry on) by saying that Christ’s own humility is suggested in this passage:

There falls on it from afar even some dark ray of the irony of God, who was mocked when He entered His own world, and killed when he came among His creatures.

This hint of Christ’s rejection when he enters in the world he authored is, I think, a valuable addition to the analogy I used in my March post. And it adds another dimension which, although I’m sure was not intended by Chaucer, is certainly relevant in today’s “Christian” culture. For the “creator” in Canterbury tales is unrecognised not only as the maker of that whole world, but in the words he presents. “Melibee” lacks the polish of poetic metre, and is an embarrassment to some modern translators, but actually speaks a deep truth that Chaucer wanted to communicate (as he did in the only other prose section of “Tales”, the Parson’s Tale).

If Christ is unrecognised as the Creator who became man today, how much more is the teaching of his Spirit, the Bible, downgraded even by many Christians as “drasty speche” that makes the “eres aken” (translated as “the words of humans searching for God” or “culturally conditioned”). Compare it to the great wisdom of our own times, or even to the original and brilliant theology coming from our academics, and it doesn’t measure up. Outmoded science, bronze-age morality and a view of God which we pilgrims of the Postmodern age have outgrown: the real Logos of God would have done a lot better than that, if he hadn’t been hindered by his human authors.

But Chaucer reminds us that the Poet is, indeed, sovereign over his own world even when he humbles himself within it. He is quite capable of speaking fluently through his work of Creation, and if he chooses to make his own most important thoughts stand out by the very simplicity and homeliness of their expression, that is the work of a Master, not of someone at the mercy of his sources. As Chaucer reminds us in the prologue to his Tale of Melibee:

…ye woot that every Evaungelist

That telleth us the peyne of Jhesu Crist

Ne seith nat alle thyng as his felawe dooth,

But, nathelees, hir sentence is al sooth,

And alle acorden as in hir sentence,

Al be her in hir tellyng difference.

For somme of hem seyn moore, and somme seyn lesse,

Whan they his pitous passioun expresse –

I meene of Marke, Mathew, Luc, and John –

But doutelees hir sentence is al oon…

Congratulations, Jon, you’ve pulled me out of the shadows with this one. (Perhaps condolences are due, rather than congrats?) I have been trying to concentrate on my work, which at the moment is an autobiographical novel of my experience teaching in juvenile detention. It applies, in this case, because I am writing the narrative portion in third person, but in other sections “I” speak directly in first person. This raises all sorts of interesting possibilities: Am “I” author, narrator, character, all of the above? In my capacity as character, can “I” dispute with the narrator?

In any case, your meditation on the prologue of John’s gospel reminds me of John 1:18, which could accurately be translated: “No one has ever seen God, but the one and only Son, who is himself God and is in closest relationship with the Father, has narrated him.”

Jumping back to your post “Monotheism 101” (linked above), the analogy between God as the author of history and a human author is also instructive in thinking about the problem of evil, to which you briefly alluded. As an author, one of the characters in my story may commit murder. Within the story, the character’s actions would have appeared to him to be the result of his own free choice, even though his background, personality, and the situation were all contrived by me, the author. In that case, am I, the author, morally guilty because of my character’s actions? Of course, the analogy is limited, but thinking about the situation does shed a little light on just one way that God “creates good and evil” without himself being stained by its corruption.

I have been keeping up, although not posting. Since I’ve broken the seal, so to speak, I’ll venture back a ways to offer a few more thoughts.

Hi Jay – it’s nice to get some feedback on Chaucer! I thought I might just get a “Whassat?” non-response!

The serious stuff on God as the author of bad characters, but not evil, comes from McCann’s Creation and the Sovereignty of God – and maybe the book analogy does too, but I can’t remember: others have used it.

Back to the work, Son – hope the book goes well!

Thank you, brother!

Man, this just makes me wish I’d written my Chaucer paper in my lit class on this topic. I can’t even remember what I did write it on, but I think it was the story about the rooster…

Noah – Chesterton says a fair bit about Chantecleer, again noting the deliberate humour: this chicken quoting all the best philosophers and sacred scriptures in his little run… more serious absurdity!

I’ll have to look into the Chesterton intro! I don’t recall if my copy had it, and it’s back at my parents’ house at the moment.

Your bit about us being the last generation that can read it straight up is fascinating to me as well. The evolution (well, it feels more like neutral drift!) of language has always intrigued me.