Rounding off (as far as I can tell today!) this loose series of posts denying that “God uses chance” in nature, I just want to look at one minor example to leave us asking questions, rather than presupposing the common scientific answers.

One recent thread at BioLogos (sorry, I’ve lost the link) talked about the hypermutation of the immune system as a “classic example” of nature’s (and ergo God’s) using chance, and this was said to be equally plausible on the larger scale of human evolution. In fact, the process was actually described as “evolution”, perhaps showing that “change over time” is an inadequate definition of evolution… I myself am rapidly evolving grey hair and a beer belly on that definition. One or two people objected that the immune system is clearly a system designed as a means to an end (whether one speaks in genuinely teleological terms or analogically). Dennis Venema replied that there was no real distinction between the situations, and implied that chance was the common denominator.

Of course, his opponent could simply have claimed in return that design was the common denominator (thus considering both immunity and evolution as physiological functions – a nod to Sy Garte’s developing ideas on providential evolution!), though he preferred to deny the correctness of the analogy altogether. But sadly the ID opponent is not a working biologist, so his metaphysical suppositions appear to carry less weight in that forum.

That Venema’s viewpoint is, indeed, not scientifically impartial is shown in my first mention of the immune system on this blog, way back in 2011, when I was reviewing James Shapiro’s Evolution – a View from the Twenty-first Century. I wrote:

One illustrative example he cites is the mammalian immune system. This is designed to produce very large numbers of very specific kinds of mutations that can respond to many different attackers. It includes systems for refining the mutations that prove to be needed for ever-increasing effectiveness. The proposition is that if the immune system is able to direct “evolution” in such an orderly way, there is every reason to suppose it happens across the board in the process of evolution.

It appears to me self-evident that whatever the immune system does, it does by a system at least as sophisticated as a computational random number generator… but even that assumes “randomness” is in the toolbox, which is what I want to question below. Evolutionary Creation at BioLogos has, for the most part, entirely ignored even secular non-random views of evolution like Shapiro’s, for reasons that remain unclear.

I’ve written in general on randomness and teleology with respect to the immune system more recently (2013) here. But today I want to pick up on a remark on the recent thread by another regular, who speaks as a working biologist (or so we are assured, though he posts pseudonymically).

I must just mention that one should take that particular poster’s expert-teaching-the -ignorant manner with a pinch of salt. Not too long ago he laid into me for describing evolution as “change in gene frequency”, which, he snapped back, no true scientist would do (because they always say “change in allele frequency”, not “gene“). He rejected the three citations I rapidly found for my usage (one on the grounds that it was in a philosophy of science text). But one I forgot was this by the leading Evo-Devo evolutionary biologist Sean B Carroll, who wrote:

Millions of biology students have been taught the view (from population genetics) that “evolution is change in gene frequencies.” Isn’t that an inspiring theme? This view forces the explanation towards mathematics and abstract description of genes, and away from butterflies and zebras, or Australopithecines and Neanderthals. (Endless Forms Most Beautiful, p.294)

Unlike the millions, this guy was correctly taught that “evolution is change in allele frequencies”, and wants to put the uneducated right. Are you more inspired now by that more correct view of theistic evolution? No? I mention this because when someone misleads you by one strident claim under the umbrella of professional authority, one inevitably takes his other claims that much more skeptically.

In this case, though, the claim itself merits no disbelief, in that he was bolstering the “chance mutation in the immune system” claim by the interesting fact that the system will often arrive at identically configured immunity sites by completely different routes. This was a valid refutation of his opponent, who had suggested that design meant the system would always follow the same beaten pathways to achieve its aims. What was invalid was his suggestion that this observation was clear evidence of randomness in the system. It doesn’t preclude it, but it certainly doesn’t endorse it.

Consider three kinds of journey.

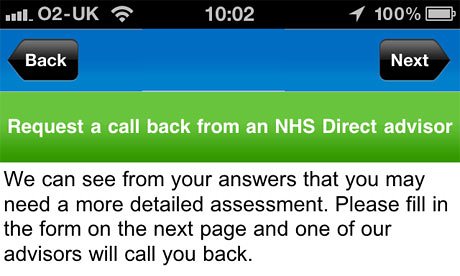

The first we might consider “algorithmic“, such as following a list of directions you’ve been given to visit somebody across the country. In this case, efficient causation is the key. Because each causal step is fixed (“turn left at the third traffic-light, follow the M5 for seventeen miles…”), the same destination will be arrived at by any two people making the journey, who follow the same algorithm. This is the way that our execrable NHS emergency health phonelines employ unskilled labour and interminable algorithms to decide what help patients will need in an emergency. The same algorithms always lead to the same destinations – though not always the same outcomes, if you happen to die before the answer “Call an ambulance!” pops out of the slot. But it’s also how computers work and, at least at the most basic level, how the DNA code works.

On the other hand, consider a “random walk“. Or in this case, a random drive, in which the driver sets out with no purpose but to discover where he’ll end up, working either by some arbitrary algorithmic rule like “take every third left then every second right and repeat…” or no rule at all. In that case, it’s unlikely that any two drivers will ever arrive at the same place without some “hidden variables,” like a selective stage, at work.

On the other hand, consider a “random walk“. Or in this case, a random drive, in which the driver sets out with no purpose but to discover where he’ll end up, working either by some arbitrary algorithmic rule like “take every third left then every second right and repeat…” or no rule at all. In that case, it’s unlikely that any two drivers will ever arrive at the same place without some “hidden variables,” like a selective stage, at work.

Thirdly, consider the “teleological” journey, of which an exemplifier par excellence is my son. He hates being caught in traffic; and mainly because there are idiot rubbernecking drivers about and some interesting statistical laws governing vehicle movements, he usually does get caught in traffic when coming to see us past Stonehenge on the A303. If he anticipates this (and likewise on other journeys), he will simply take the next by-road, and follow instinct, the sun or signposts until he eventually reaches our house. He’s discovered beautiful villages and landscapes most Englishmen never see that way.

But because his journey is goal-orientated, there are many “correct” routes to the same destination, and so it’s always interesting to ask him how he got here. That pattern, in fact, is the pattern of any teleological process. In my medical practice, for example, having a good idea from my professional nous where my diagnostic process was ending up, the actual steps I took in achieving my aim varied quite a lot, unlike a telephone algorithm.

If I ask several people to get me some potatoes, some may dig them from their gardens, others visit various supermarkets or farm shops – and all will take different routes, use different muscles, and even transport the vegetables in a different manner. The same is true if I ask someone to make a chair, bake a Victoria jam sponge, explain the story of Jesus or any other purpose-led activity.

On the face of it, taking the immune system as a system, it does not look lawlike or “algorithmic” if it achieves the same ends by different molecular routes. But neither does it look like a random walk in that its varied journeys all tend to end up with much the same set of immune capabilities.

On the face of it, taking the immune system as a system, it does not look lawlike or “algorithmic” if it achieves the same ends by different molecular routes. But neither does it look like a random walk in that its varied journeys all tend to end up with much the same set of immune capabilities.

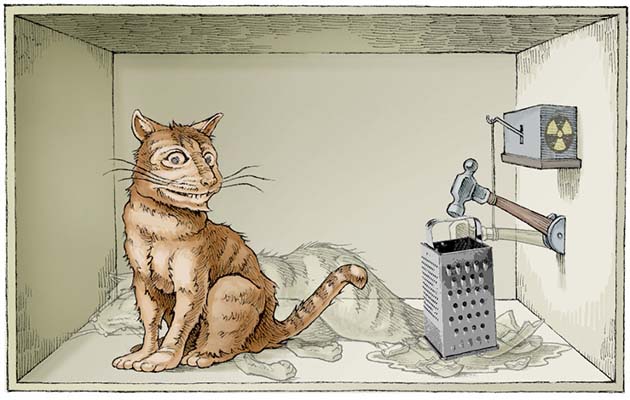

No, in terms of pattern, it appears as if the immune system, in some sense, has its functional ends in view, and is far less concerned about its precise means of getting there. There is more than one way to skin a cat. The fact that the cats always end up skinned is what gives away the teleology.

Now, in the case of “inherent teleology”, as I described in my previous post, the purpose may be difficult to attribute to intelligence (except at the First Cause level), and so one stage of a process might involve a “random walk” in a way that God’s direct providential activity could not – though God will still be providentially involved. I described there the predator that seeks prey purposefully by a “random walk” strategy. But from the physical point of view it is the total process that should be considered: a child may tip all his toys randomly out of the toybox – but with the clear aim of picking out his favourite car from the mess on the floor.

Just so may an immune system generate a mass of possibilities by an undirected means in a process that is, however, carefully designed to select what’s required physiologically from those possibilities. If so, then maybe Dennis Venema’s extrapolation of the principle to evolution carries some weight – and evolution is a physiological system (or perhaps rather a “population physiological” system!) by which populations produce needed change.

As discussed in the last post neither case would equate to God’s using chance: the providential guidance of specific situations is orthogonal to physiology. But it would have enormous implications concerning how such teleological systems would arise in the first place, apart from some greater purpose.

Skinning cats is about design all the way up.

I remember that Stonehenge traffic from when I visited 3 or so years ago–really terrible, but I guess we were part of the problem! A benefit of living in Houston is that there is almost no tourism (which is a shame because we’ve got a great food and art scene). That’ll change in February with the Super Bowl coming to town, I guess.

Now, in the case of “inherent teleology”, as I described in my previous post, the purpose may be difficult to attribute to intelligence (except at the First Cause level), and so one stage of a process might involve a “random walk” in a way that God’s direct providential activity could not – though God will still be providentially involved. I described there the predator that seeks prey purposefully by a “random walk” strategy. But from the physical point of view it is the total process that should be considered: a child may tip all his toys randomly out of the toybox – but with the clear aim of picking out his favourite car from the mess on the floor.

Is this much different from “the eyes of faith”? I know you’re saying that there seems to be an undeniable teleology in evolution (correct me if you’re not!), but would you say it ultimately comes down to seeing God’s hand where others may not?

Hi Noah.

First, to make sure this post is duly distinguished from its fellows: this one is about the pattern of the “search” observed, and principally that what was described as “random” (the immune hypermutation) is actually part of a process that has the pattern characteristic of a teleological process (many routes to the same destination). That seems worthy of note.

As for randomness itself, in the sense of stochastic undirected processes, it’s formally indistinguishable from the contingent choices of a purposeful being: and so, for example, without a knowledge of language, English prose is not unlike a random string of letters (though an overall statistical pattern of how often letters appear that’s characteristic of English emerges in large samples).

If the purposeful being is unobservable in a “random” process*, as in God’s case, then it comes down to whether one believes (as a philosophical choice) that Epicurean chance can produce the order inherent in living things, so it is a matter of faith. But not unilaterally a belief in God, but a belief either in God (or some other intelligent being) or in the proposition that pure chance can produce order, which is actually a bigger ask.

* Assuming here that the probability distribution is not known to be an artifact of some known lawlike process – which can never be known in rigorous detail without the process ceasing to be random any more, and being predictable.

Thanks for the clarification, I see what you’re saying right now. I agree with this line of thought, but allow me to take a devil’s advocate position so I can get more clarity!

it comes down to whether one believes (as a philosophical choice) that Epicurean chance can produce the order inherent in living things, so it is a matter of faith.

Is this a distinguishable position from the argument from irreducible complexity? I’ve seen it demonstrated that this argument doesn’t have much strength (from believers and nonbelievers alike). I’d be inclined to agree with the above point, but I’m wary of it because of how sketchy the IC argument is and there seems to be a connection.

Hi Noah

The argument probably depends more on Aquinas than Behe.

Behe starts from “known natural processes”, taking chance as a given and saying that the kind of chances we find in evolution as now described would not make irreducible complexity likely. He argues (basically) that since chance has to be corrected by selection at every stage or changes will be lost, an organ that only functions with many components will not evolve.

My point is more basic: that there is no true chance in the world – only unknown true causes. If there were, it would be incapable of producing order, by definition.

A coin toss has a 50% chance of head or tails because it is actually ordered. An Epicurean coin toss would, to use a wonderful phrase from one of my patients, produce Marble Arch and Christmas as often as heads and tails.